No Fur Thank You!

The Israeli legislature has been debating the legality of the local fur trade since 2009, when the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Law (Amendment 8) was submitted to the Knesset.

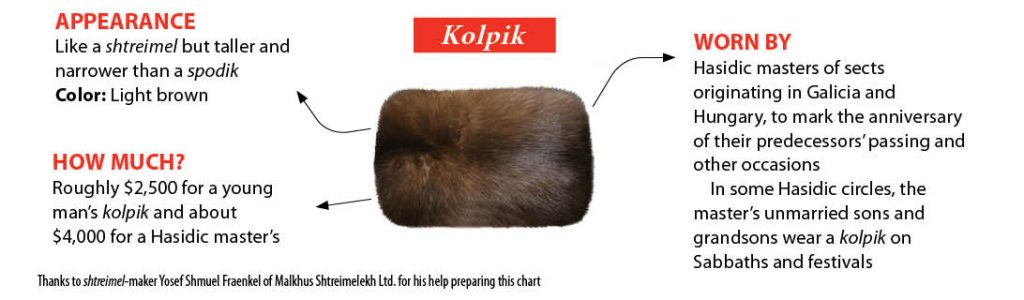

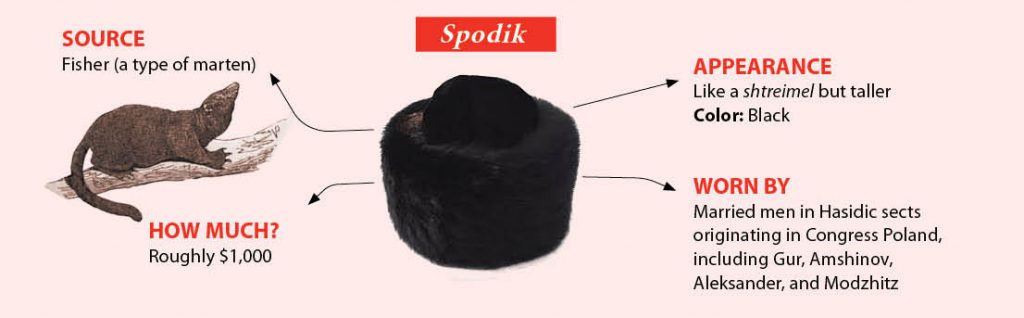

Demand for fur is very limited in Israel’s hot climate, but had the law passed, the Jewish state would have set an example for the world by becoming the first country to ban fur trafficking. (Other jurisdictions have since adopted such legislation.) Politics killed the bill, however. Among other sticking points, Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Knesset members objected that such a law would prohibit the manufacture, import, and sale of Hasidic headwear: the shtreimel (plural: shtreimelekh), spodik, and kolpik.

-

-Religious Markings

One mark of Hasidic communities is the distinctive garb worn by males. Over and above the various frocks, socks, and sashes, the fur headdress of the Hasidic faithful features across museum exhibitions, portraits, and art installations. The regal-looking headgear is worn by men on the Sabbath, festivals, and other significant occasions, such as weddings – regardless of the weather.

Hasidic fur hats come in different styles. Broadly speaking, Hasidic groups originating in Ukraine (where Hasidism began), Russia, Galicia, Hungary, or Romania don the short, wide, brown shtreimel, traditionally made from animal tails. These courts include the Boyan, Munkács, and Sanz Hasidim.

Groups that trace their roots to Congress Poland (annexed by Russia in the 18th century) wear the taller, narrower, and darker spodik, made from pieces of black fur (sometimes dyed that color) and therefore cheaper. Gur, Amshinov, and Aleksander Hasidim sport a spodik.

Less well-known is the kolpik – colored like a shtreimel but shaped like a spodik. The kolpik is worn by some Hasidic masters to mark the anniversary of a saintly ancestor’s death and other occasions. In certain Hasidic courts, the kolpik is also donned by the rebbe’s unmarried sons and grandsons.

These rules have their exceptions. There are non-Hasidim who wear a shtreimel: the Perushim, descendants of the disciples of Rabbi Elijah, the Gaon of Vilna, who arrived in the Holy Land (mainly Jerusalem) in the 18th century. And there are Hasidim who don’t: the Lubavitchers, whose felt fedoras resemble those of the non-Hasidic ultra-Orthodox. And spodik wearers call their hats shtreimelekh, confusing everyone.

Segula mag | סגולה

Segula mag | סגולהThe First Shtreimel

Fur hats are mentioned nowhere in the Bible, Talmud, or classic codes of Jewish law. So how did the shtreimel become mandatory for most Hasidim?

According to one legend, the shtreimel began as an anti-Semitic ploy of Sigismund I (1467–1548), king of Poland, who ordered Jewish men to wear animal tails on their heads on the Sabbath, thereby repelling their wives. As the original reason for the practice faded from memory, the tails became a mark of distinction to be donned on special occasions.

This colorful account was advanced by many, including scholar of Hasidism Ahron Marcus (1843–1916), Nobel laureate S. Y. Agnon (1888–1970), and Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Halberstam of Sanz-Klausenberg (1905–1994), who founded the Sanz community in Netanya. Yet the story has no historic basis.

True, Jews were obliged to wear special hats, and animal tails were used to debase people, as depicted in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 16th-century painting The Beggars. But Sigismund I was far from anti-Semitic: immediately upon ascending the throne, he cancelled his brother’s edict of Jewish expulsion. Moreover, there is no evidence of any decree requiring Jews to wear fur hats.

In stark contrast to this tale of humiliation, the shtreimel also resembles the sable-trimmed Russian Imperial crown known as Monomakh’s Cap, apart from its bejeweled cap topped with a cross. Designed in the 13th or 14th century, this princely attire is preserved in the Kremlin armory in Moscow.

-

-Regal Shreimel Monomakh’s Cap crowned Russian Imperial royals from as early as 700 Photo: Ramon

Others have argued that the furs were merely standard winter gear in the frigid local climate.

Communal legislation, prenuptial agreements, and other documentation dating from the 17th century indicate that some form of shtreimel predated even the spiritual father of Hasidism, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov (circa 1700–1760).

For example, in the memoirs of the first recorded rabbi of Kutno, Poland – Rabbi Moshe Yekutiel Kaufman – the author describes how he fled his home in 1682 after being falsely accused of murder: “I changed my clothes and adjusted my shtreimel, so they wouldn’t recognize me.” Whatever this adjustment was, it’s unclear how it masked his identity.

Another shtreimel appears in a 1694 document – but not on the head of a Jew. The Jews of Opatów, Poland, kept a log beginning in 1666. Sadly, this record was lost during the Holocaust, but there are scholarly copies. One entry lists a communal expense: “For the deacon’s shtreimel : thirty gold [coins]” (Nahum Sokolow, “The Opatów Community Log,” He-asif 6 [5554], p. 142 [Hebrew]).

Status Symbol

Shtreimelekh were also fashion accessories and status symbols. In the early 18th century, the Jewish community of Boskovice, Moravia, regulated the wearing of fur hats by women whose husbands paid minimal communal taxes:

Anyone who doesn’t remit two coins to the [communal] fund – his wife is not permitted to go around with a shiny scarf or a Prague hat. Rather, she may wear only a shtreim hat with marten-fur trimmings. (Yehuda Leib Bialer, ed., Min Ha-genazim [From the Vaults], vol. 2, p. 119 [Hebrew])

(Thanks to its diminutive final lamed, the word shtreimel means a small or otherwise distinguished shtreim, or fur hat.)

Like many other communal bylaws – in Boskovice and elsewhere – this rule was intended to prevent low-income households from overspending on women’s apparel due to social pressure. The regulation may also have aimed to avoid unwanted attention from hostile gentile neighbors. In any case, headwear indicated one’s tax bracket within the Jewish community and hence his economic standing. A shiny scarf or a hat from Prague was clearly more prestigious than a common, locally manufactured shtreim.

-

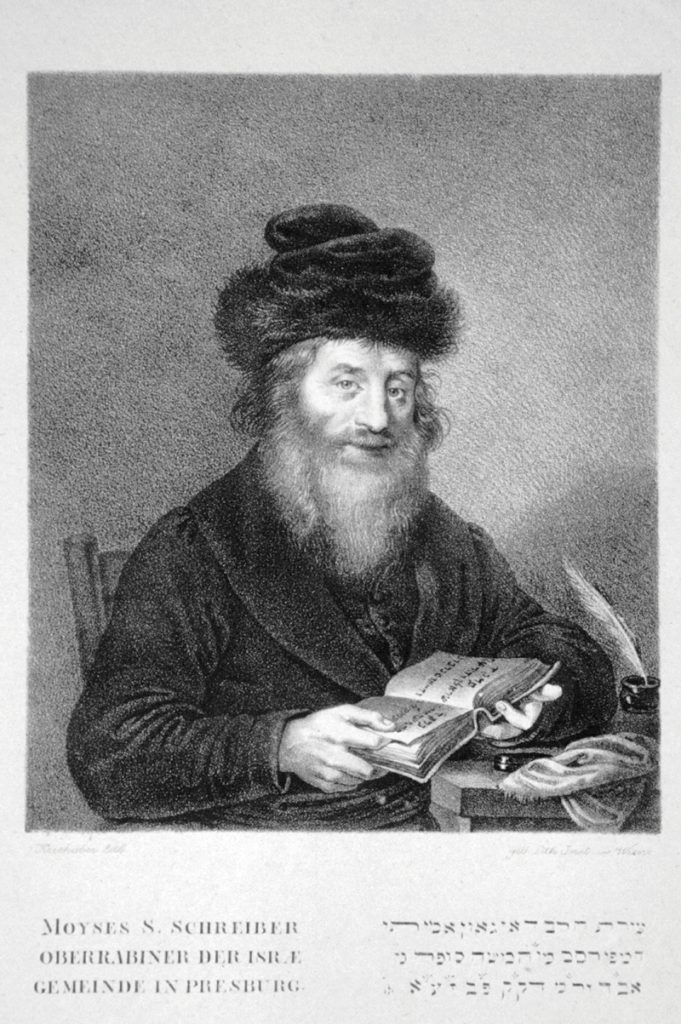

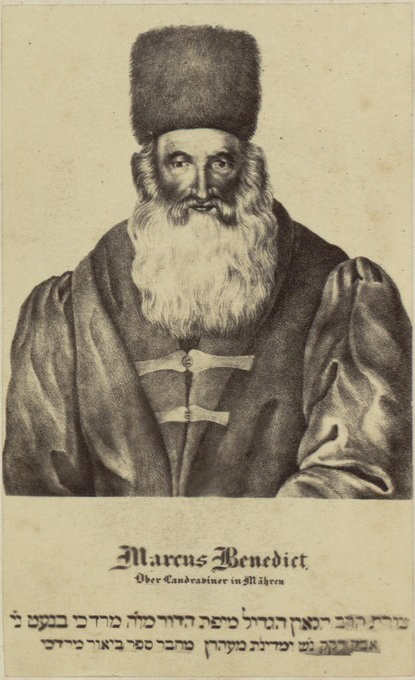

-Rabbinic status symbol. Likenesses of some of Hasidism’s most vocal early opponents show them sporting a shtreimel, indicating that the hat wasn’t always associated with the movement. Rabbi Yehezkel Landau (a.k.a. Noda Bi-Yehuda), Rabbi Moshe Sofer (a.k.a. Hatam Sofer), and Rabbi Mordekhai Banet of Nikolsburg

A communal ordinance enacted in Śniadowo, Poland, and transcribed in 1768, distinguishes between shtreimel and spodik – this time atop male heads – as a reflection of the wearer’s scholarship and attendant social status:

Not everyone who wishes to take a crown for his head may take [it]. For this reason, we legislated this ordinance so every person will crown himself according to the honor he deserves. That is, someone who knows how to study a chapter of Mishna may wear a hat known as a shtreimel […].

The less learned had to make do with a cheaper head covering:

[…] and the aforementioned tradespeople, who aren’t permitted to wear a shtreimel, may also not attend synagogue on the Sabbath and festivals wearing any hat besides […] a spodik. (Shlomo Eidelberg, “The Śniadowo Log,” Gal-ed 3 [1976], pp. 307–8 [Hebrew])

Clearly, in the 18th century, shtreimel and spodik divided rich from poor and laymen from intellectuals.

Once established as a status symbol, the shtreimel naturally became rabbinic garb. This “promotion” took place well before the Hasidic movement gained momentum. Witness the fur hats in likenesses of rabbis as early as Yehezkel Landau (1713–1793), chief rabbi of Prague, author of the Noda Bi-Yehuda responsa, and – ironically – an early opponent of Hasidism. Another rabbi depicted with a shtreimel is Mordechai Banet of Nikolsburg (Moravia, 1753–1829). And the ex libris of the Davidson family shows patriarch Rabbi Haim Davidson (1760–1854), chief rabbi of Warsaw, and his son Naftali, both wearing fur hats.

Admittedly, these representations could be anachronistic, implying only that these men’s descendants thought their ancestors underdressed without a spodik. Yet shtreimelekh also appear in rabbinic portraits painted in their subjects’ lifetime and in photographs of rabbis in no way associated with Hasidism. Evidently, for 18th- and 19th-century rabbis, a shtreimel went with the job.

When Did the Hasid Get His Hat?

All the shtreimelekh mentioned so far have no connection to Hasidism. A fur hat was promised to Rabbi Avraham Yehoshua Heshel of Opatów by his bride’s family prior to their wedding in 1764 (Abraham J. Heschel, “Unknown Documents on the History of Hasidism,” YIVO Bleter 36 [1952], pp. 120–1). But he wasn’t yet a Hasidic master, for there was still no Hasidic movement to speak of. His in-laws simply wanted his head warmed by the fanciest chapeau available.

Early Hasidic leaders left few portraits and descriptions of themselves, nor did their followers depict them. Nonetheless, two sources indicate that at the end of the 18th century, the shtreimel had yet to be associated with Hasidism.

The first source relates to Rabbi Dov Ber (d. 1772), the Maggid (Preacher) of Mezritch (today Międzyrzec Korecki), one of the Baal Shem Tov’s successors. Precocious young Solomon Maimon (1754–1800), later a leading German Jewish intellectual, visited the Maggid’s court shortly before his death (hoping to experience what he considered a “secret society”). Writing his memoirs some twenty years on, Maimon vividly recalled the Maggid’s white clothing, white shoes, and even white snuffbox – but no fur hat.

Similarly, writing sometime before 1800, merchant Dov Ber of Bolechów recorded what he described as the age-old practice of wearing a coat and hat for prayer, then contrasted it with the conduct of Jews in Podolia and Ukraine, where Hasidism was developing:

And they don’t prepare the afore- mentioned garments for themselves in order to pray in them in the holy synagogue. Rather, whatever clothing one [wears] to go out to the market all day, in those [clothes] he prays and studies – if he can [study] – without said rabbinic garb. (Dov Ber [Birkenthal], Divrei Bina, National Library of Israel, Ms. Heb. 8°7507, completed 1800, pp. 19–21)

Again, no fur hat.

The engravings in Léon Hollaenderski’s The Jews of Poland show a wide variety of Jewish costumes. Left to right: a Lithuanian group portrait, a Hasidic husband and wife, and a couple from Warsaw. The Hasid stands out not for his fur hat but for his inebriated, bohemian air

Equally instructive is Les Israélites de Pologne (1846), a history of Polish Jewry by Léon Hollaenderski. One of the six priceless engravings illustrating this work, Le Chasside et Sa Femme (The Hasid and His Wife), is often trotted out to demonstrate what a Hasid looked like in the mid-19th century. As expected, this fellow is wearing a fur head covering. But so are the non-Hasidic Jews in the other illustrations. Hollaenderski’s Hasid stands out not because of his hat, but because of his dishevelled look – wild hair, scraggly beard, and an unbuttoned overcoat that reveals his fringed tzitzit garment. He holds a pipe and bottle as if he has just taken a puff and is about to take a swig. All in all, Hollaenderski’s Hasid doesn’t cut an impressive figure. His spodik is rather plebeian; certainly not regal. In short, what makes Hollaenderski’s Hasid identifiable as such isn’t his fur hat.

The Tsar Intervenes

What really transformed the shtreimel into a signifier of Hasidic identity may have been the 19th-century clothing decrees imposed by Tsar Nicholas I as part of broader social engineering initiatives. His attempts to “reform” his Jewish subjects included the demand that they choose between two styles of dress: German (including a short jacket) and Russian (a long jacket and a fur hat).

-

-Isidor Kaufmann’s paintings of Hungarian Jewry preserved a world on the brink of destruction. Man with kolpik, 1910

The decrees sparked fierce debate among the Jews. Did Jewish law forbid them to don this gentile clothing? Were they required to choose martyrdom rather than trade in their wardrobe?

These questions were tackled by such jurists as Nehemia Halevi Ginsburg of Dubrovno (1788–1852); Yehuda Salkind (d. 1857), rabbi of Vilkomir, then of Dvinsk; Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (1789–1866), the third Lubavitcher Rebbe and a prolific writer of responsa; and Shelomo Drimer (circa 1800–1872), rabbi of Skała, Galicia. Marshalling a variety of arguments, these scholars explained why the Russian legislation didn’t mandate self-sacrifice, and why changing clothes was permissible – though far from preferable – according to Jewish law.

Traditional Jews generally chose the Russian option, distancing themselves sartorially from secular, modern European modes of dress.

After Nicholas’ death in 1855, his successor pursued different policies, and the furor surrounding the clothing laws subsided. They did have some permanent effect, however. Jews who wished to isolate themselves from their non-Jewish, assimilationist surroundings stuck with the Russian garb, which was dying out in eastern Europe. So it was that the “Russian” fur hat and long coat became Jewish clothing, worn by the arch-traditionalists to differentiate themselves from everyone else.

The Russian legislation peaked in mid-century, having been expanded to prohibit – among other things – beards, sidelocks, silk clothing, long jackets, and fur headdresses. Thus, an 1853 Warsaw proclamation published in Polish and Yiddish banned “pelts mittsen” – fur caps (E. Tscherikower, ed., Historishe Shriften fun YIVO, vol. 1 [Warsaw, 1929], p. 733).

-

-Inadvertent inventor of the Hasidic dress code? Nicholas I, who outlawed stereotypical Jewish attire. Portrait by Horace Vernet, circa 1830

Yet “veteran rabbis” were exempt from the decree, perhaps generating the notion that rabbinic apparel included fur headwear. This perception may have had a ripple effect: if the recognized and respected heads of the Jewish community – the “most Jewish” Jews – wore fur hats, surely this was traditional Jewish attire.

Such an explanation of the rise of the shtreimel has a distinctly Hasidic flavor: if any Jew could devote his life to God, if anyone could be holy, then surely anyone could and should wear a shtreimel. The Hasidic masters may then have adopted the kolpik on certain occasions, preserving a visual distinction between the leader and his followers.

Confusing the Issue

The shtreimel didn’t become exclusively Hasidic overnight, however. At the turn of the 20th century, it was not uncommon to find a non-Hasidic head beneath the tailored tails. Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook (d. 1935), Ashkenazic chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine, was no Hasid (though some say his background was at least partially Hasidic), but he wore a spodik.

Even non-Jews still wore shtreimelekh. In 1912, for instance, Russian artist Boris Kustodiev painted himself outside the Trinity Lavra of Saint Sergius Monastery, spiritual center of the Russian Orthodox Church. The snowcapped buildings and trees contrast starkly with his dark fur coat and what looks like a kolpik.

By 1937, though, in North America at least, the Hasid and his shtreimel seemed inseparable. A Canadian Jewish newspaper reported that year on the suspension of train service to a town in Western Ukraine on Saturday, because “the ministry of railways has appointed Meyer Lefkowitz, a pious, streimel-wearing Chassid [sic], as station-master. In order not to force Lefkowitz to violate the Jewish Sabbath, the railways officials agreed to keep the station closed on Saturday” (“Trains Don’t Stop Here on Saturday,” Jewish Western Bulletin, September 14, 1937, p. 1).

Though Lefkowitz wouldn’t have worn his shtreimel to work on weekdays at the station, the reporter associated him with this headgear. On or off the Hasid’s head, the shtreimel had become a symbol.

Holy Shreimel!

Rabbi Shlomo Halberstam, the Hasidic master of Bobov, lost his wife and two children in the Holocaust. After the war, he and his son Naftali Tzvi arrived in London penniless. In 1946, the rabbi wrote to one of his American followers, who was trying to obtain a visa for him:

I have no shtreimel for the Sabbath and have so far fulfilled that obligation with a borrowed shtreimel. As a matter of extreme urgency, therefore, a good shtreimel must be purchased and prepared for me in honor of the Sabbath. My hat size is 57 or 57.5. I do, thank God, have a kapoten [jacket] and halet [coat], which I had sewn here. (Elimelekh Elazar Orenberg, Arzei Ha-Levanon [Cedars of Lebanon], 1967, p. 207)

-

-Rozhiner Hasid’s shtreimel? Artist Boris Kustodiev poses outside the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius Monastery. Self-portrait, oil on canvas, 1912

-

-The subject of this painting by 17th-century Dutch artist Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten is traditionally identified as Rabbi Yom Tov Lipmann Heller, author of the eponymous Tosfot Yom Tov commentary on the Mishna, who was imprisoned in Vienna for forty days in 1629. Yet van Hoogstraten was only two at that time, and the work wasn’t produced until 1653

Though the visa was undoubtedly important to Halberstam, his lack of Hasidic garb was also a concern. Even if he didn’t think Jewish law “obligated” him to wear a shtreimel, the hat had become so entrenched in Hasidic custom that he felt he couldn’t appear in public on the Sabbath without one.

The shtreimel even acquired mystical significance. According to a 1914 Hasidic publication, Rabbi Pinhas Shapira of Korzec (1726–1791, another disciple of the Baal Shem Tov) explained that on the Sabbath, Jews can spiritually elevate even lowly things. Thus, even such humble foods as gala (calves’-foot jelly, also known as ptcha), onions, and kasha are transformed into Sabbath “delicacies,” and even animal tails become a crown – in the form of shtreimelekh.

A more playful tradition attributed to Rabbi Pinhas (in A. Wertheim, Halakhot Ve-halikhot Ba-Hasidut [Jerusalem, 1960], p. 196) interprets the Hebrew word Shabbat (Sabbath) as an acronym for shtreimel bi-mekom tefillin – a shtreimel instead of phylacteries. In other words, the Sabbath shtreimel replaces the weekday commandment to lay tefillin. Both phylacteries and the Sabbath are described in the Bible as a sign of Israel’s covenant with God, and rabbinic tradition links the two symbols. Hence the deeper meaning of the Hasidic fur hat: just as phylacteries signify a Jew’s relationship with God, so does the shtreimel.

Safe Keeping

Israel’s anti-fur bill has gone through sixteen drafts, all rejected. This despite lobbying by animal rights organizations, and despite a proposed clause excluding Hasidic headwear from the ban in view of the shtreimel’s traditional religious importance.

Eric and Edith Matson Collection, Library of Congress

Eric and Edith Matson Collection, Library of Congress Ultra-Orthodox Jerusalemites – Hasidic or not – long donned their own particular shtreimel, distinguished by its relatively low height. Jerusalem, circa 1900 Photo: Eric and Edith Matson Collection, Library of Congress

For centuries, the fur hat protected its wearer from the elements. Among Hasidim, however, the wearer protects the shtreimel – both physically, by means of simple plastic covers or oversized raincoat hoods, and metaphorically, safeguarding it amid a swiftly changing religious climate. No longer a mere hat in the service of man, the shtreimel is today a sacred object, pressed proudly into the service of the Divine.