Musings on history, alternative history, and theology based on the surprising final scene of Tarantino’s film.

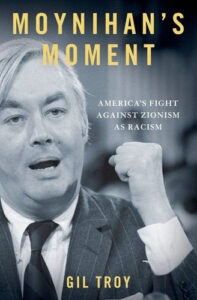

Moynihan’s Moment: America’s Fight against Zionism as Racism

Gil Troy

Oxford University Press,

2013, 358 pages

On November 10, 1975, the United Nations General Assembly, by a vote of 72 to 35 with 32 abstentions, resolved that Zionism is racism. After the vote the American ambassador to the UN, Prof. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, took the podium to state: “The United States rises to declare before the General Assembly of the United Nations and the world that it does not acknowledge, it will never abide by, it will never acquiesce in this infamous act.”

Moynihan knew that, though the resolution originated with the Arab states, it was a propaganda ploy cooked up in Moscow and advanced by an unholy alliance of communist and third world despots. Its purpose was intended to taint Israel – and by association any Western democracy that rose to its defense – with the stain of racism. Moscow’s was the logic of the wolf pack: let one vulnerable sheep out of the herd of decadent democracies be devoured, and the rest would run scared for good. “There will be more [such] campaigns,” Moynihan warned. “They will not abate . . . for it is sensed in the world that democracy is in trouble. There is blood in the water and the sharks grow frenzied.” But Moynihan didn’t scare. In the weeks before the vote and in his speech afterward, he denounced the resolution and asserted the moral superiority of free societies over repressive regimes of any kind.

Moynihan’s stand proved popular throughout the United States. The 1970s were a difficult decade for America. Race relations were at a nadir, a weak economy caused the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates that the United States had instituted after World War II, and the Watergate scandal forced President Richard Nixon from office. The Soviet Union was arming at an alarming rate, and in April 1975 South Vietnam fell to the communist north, ostensibly marking America’s global decline. Against this background, Moynihan’s spirited defense of democracy heartened many. A year later it propelled him to the Senate, where he served for twenty-four years.

Not everyone approved Moynihan’s stand, however. America’s radical left preferred the Soviet narrative that the United States was racist, aggressive, and exploitative. In addition, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger begrudged Moynihan’s popularity – both men were Harvard professors – though Moynihan’s prestige never equaled Kissinger’s. Moreover, Kissinger’s policy of détente assumed that the United States was indeed in decline relative to the USSR. An uncompromising affirmation of the moral distinction between freedom and despotism did not mesh with that policy. (It is not clear that Kissinger believed democracy conveyed any advantages, moral or other.) Kissinger characteristically supported Moynihan to his face while undermining him behind the scenes, forcing the ambassador to resign in January 1976.

.

From Roosevelt to Reagan…

Prof. Gil Troy of McGill University in Montreal, a historian and a noted advocate of Zionism, has written Moynihan’s Moment to illuminate the parallels between Moynihan’s time and ours. As in the 1970s, the thesis that Zionism is racism is pushed by radical leftists and third-world despotisms. Troy believes the content and rationale of Moynihan’s defense of Zionism in 1975 remain valid, and he criticizes contemporary American politicians such as Barack Obama and Condoleeza Rice who “compare the Palestinian quest for independence with the African American quest for civil rights . . . This reading . . . link[s] the United States and Israel as the sinning successors to South Africa’s apartheid regime.”

The book has an additional, unspoken agenda. Moynihan in the 1970s and Troy today belong to the moderate left, which champions democracy, the free market, and individual enterprise. Troy’s book is intended as a vindication of this moderate Left. Moynihan himself was a member of the coalition of minorities whom Franklin Roosevelt organized and led to political triumph in the 1930s. Roosevelt went on to found the federally funded welfare state.

Born to a family of Irish extraction that fell apart during the Depression, Moynihan attended New York public schools, volunteered for naval officer training at age seventeen in 1944, and worked as a longshoreman in New York. Yet his intellect and ambition were voracious. He enrolled in New York’s City College at age sixteen, earned a Ph.D. at Tufts University (specializing in the sociology of America’s black community), and become a tenured professor at Harvard, the heart of the WASP establishment. For Moynihan and many others, Roosevelt’s America was a land of opportunity, and he defended it passionately.

As the author points out, Moynihan’s vigorous, self-confident advocacy of free societies prefigured the themes deployed by Ronald Reagan, a Republican, to beat Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election. Yet – though Troy omits this point – it was not Reagan’s robust defense of American democracy that boosted the United States’ international standing in the subsequent two decades. If the U.S. had indeed been in decline, as Kissinger assumed, Moynihan’s and Reagan’s rhetoric would have been exposed eventually as empty posturing. It was “Reaganomics,” the reduction of taxes and regulation in favor of the free market, that led to twenty years of rapid American economic growth and the country’s return to world leadership. This advantage was unfortunately squandered by President George W. Bush in the first decade of this century.

…To Obama

As in Moynihan’s time, the United States faces an economic crisis that is sapping its international strength. Its leaders reject the traditional American embrace of free markets and economic liberty, and believe in accommodating the cultural narratives of despotic and fanatical societies. This two-pronged perspective is internally consistent and turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Upon reflection, Barack Obama would find chilling parallels between his narrative of America and that of Nixon and Kissinger. It is not clear that any left, whether Obama’s or Troy’s and Moynihan’s, can find a way out of this conceptual and policy trap.