Eighteenth-century birth registries list a surprisingly large number of “unwed” Jewish mothers, but immorality wasn’t the issue

The friendly American yeshiva student who frequented the Central Archives to research his Bavarian ancestors found quite a few, but he was disturbed by the notation in a birth registry next to the name of a female relative: “unehelich” – unmarried. The young man frowned. No such fact had ever been mentioned in his family. He didn’t visit the archives again.

Traditionally, Jewish communities recorded marriages, divorces, deaths, and burials, but not births. Circumcisions were listed in the mohel’s (circumciser’s) personal notebook – though this information seldom reached community archives – but female births weren’t recorded, except in notes occasionally handwritten in Bibles or prayer books.

Toward the end of the 18th century, most of Europe began regulating the registration of births, marriages, and deaths. Among Jews, the registrar was usually the community rabbi or, if they were too few to have one, the local pastor (which explains why Jewish entries are sometimes found in church registries).

Unwed Mothers?

Some Jewish communities record surprisingly many “unwed” mothers, but this label doesn’t necessarily mean the community was less traditional or had looser moral standards than generally supposed.

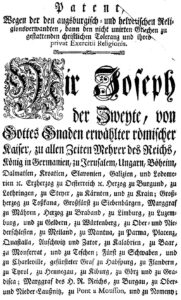

Most of these women were in fact married by a rabbi in accordance with Jewish law and custom – but unbeknownst to the authorities. These “quiet weddings” came about because certain European countries limited the number of Jewish marriages, attempting to reduce their Jewish populations. Legislated mainly in the 18th century and repealed during the 19th, these quotas usually meant that only one son per family could be registered as married. In Prussia, for instance, a 1714 law allowed only one son to inherit his father’s residential rights; any brothers could marry only if they possessed considerable means and paid a hefty fine.

Empress Maria Theresa, who ruled Austria in the second half of the 18th century, was particularly infamous in this context. Her grandfather Leopold had expelled the Jews from Vienna in 1670, and her father, Carl VI, passed the “Familianten” laws in 1726, limiting the size of Jewish communities in Moravia, Silesia, and Bohemia (Austria was by then effectively free of Jews). Continuing the family tradition, Maria Theresa expelled the Jews from Prague in 1745, allowing their return only after massive international intervention (initiated by influential Jews in various countries) in 1748.

After the first Partition of Poland in 1772, Galicia became part of Austria, doubling the number of Jews under Habsburg rule. The rules limiting the number of Jewish marriages were then applied to Galician Jewry too.

This, then, is why so many Jewish mothers were listed as “unwed.” Sons who lacked permission to marry locally and were either unable or unwilling to go elsewhere tied the knot “quietly,” without registration. So did women barred from their fiancés’ hometowns by quotas. The children of these couples were deemed “illegitimate.”

Register or Else

These restrictions were gradually abolished during the 19th century, as Jews’ legal status improved. But though there was no longer any compelling reason not to register marriages, the process was cumbersome, requiring a journey to the county seat and proof of financial ability. Many Jews (and Christians!) preferred to skip this step or at least postpone it until unavoidable. As a result, elderly couples sometimes came to register accompanied by their children and grandchildren!

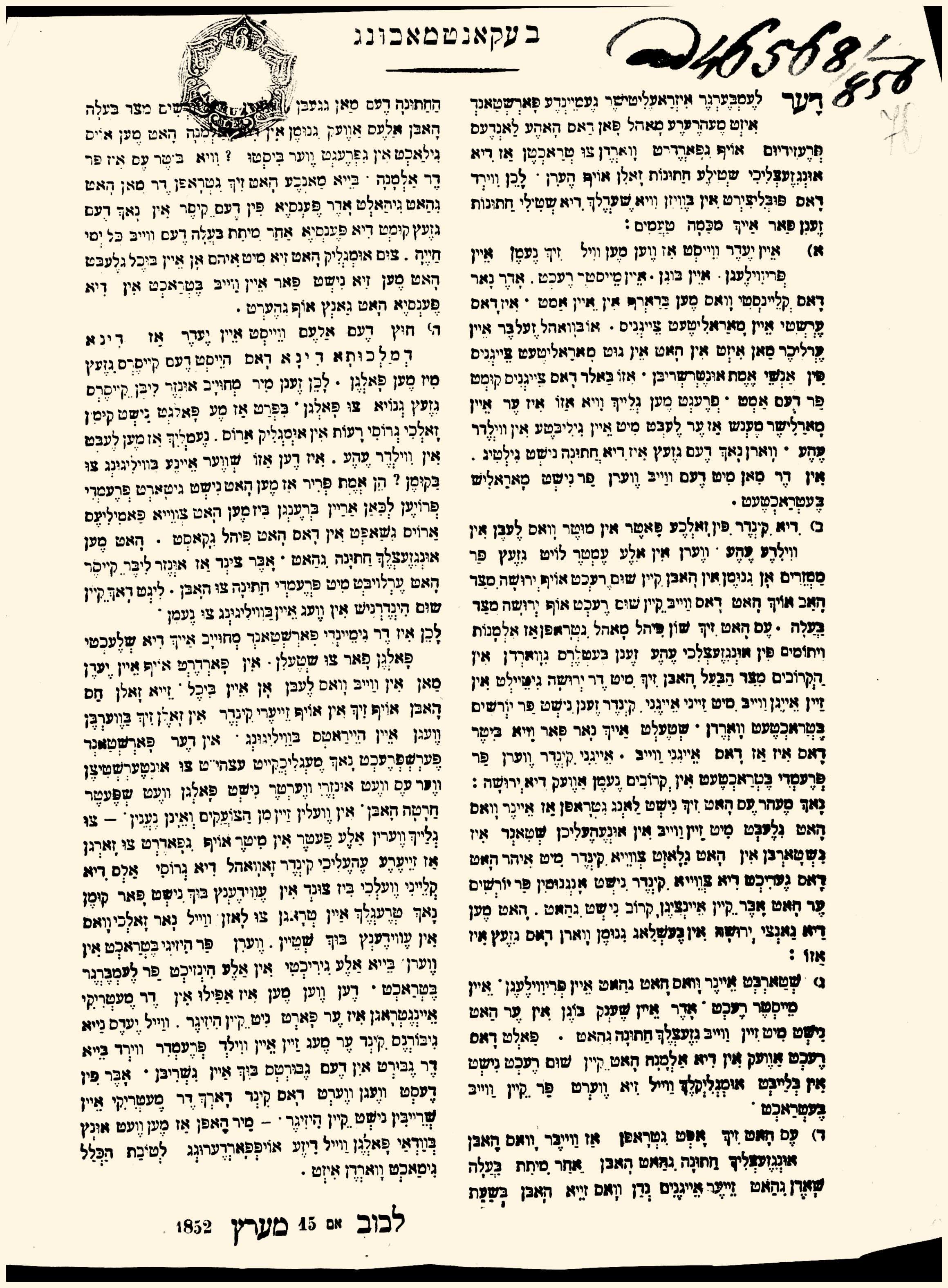

The authorities eventually cottoned on and insisted that communities stop unregistered marriages. A notice (Bekanntmachung) published in Yiddish in Lemberg (Lvov) in 1852 was a typical response.

The announcement warns of the many drawbacks of such unions. A man living with a woman “out of wedlock” could not be certified “moral,” disqualifying him from certain positions. His children were regarded as illegitimate, and upon his death, both they and their mother forfeited his inheritance (including any pension) as well as any dowry the wife had brought with her into the marriage. Any property went either to his brothers or to the government, leaving the widow and orphans destitute. In short, anyone disregarding this warning would be very sorry indeed – and have no recourse at all.

Furthermore, the notice invoked the Jewish legal principle of “Dina demalkhuta dina,” which recognizes the law of the state as binding. It referred to “our beloved emperor, Franz Josef,” under whose liberal rule (1848–1916) Jews lived without discriminatory regulation, including marital restrictions. In these times, it concluded, there was no reason or excuse for not registering Jewish marriages.

Such exhortations were not entirely effective. My late mother, Nehama Gittel, born in 1899 – whose father, Jehiel Wallach, served as secretary to the Hasidic master of Husiatyn in eastern Galicia – attended school under her mother’s maiden name. In the eyes of the Austrian government, her parents weren’t married. As a result, I learned the name of my grandmother, Rachel Leah née Berfel, who perished in Theresienstadt.

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People rescues, restores, and preserves historical documents concerning the Jewish people from communities worldwide, from the Middle Ages to the present