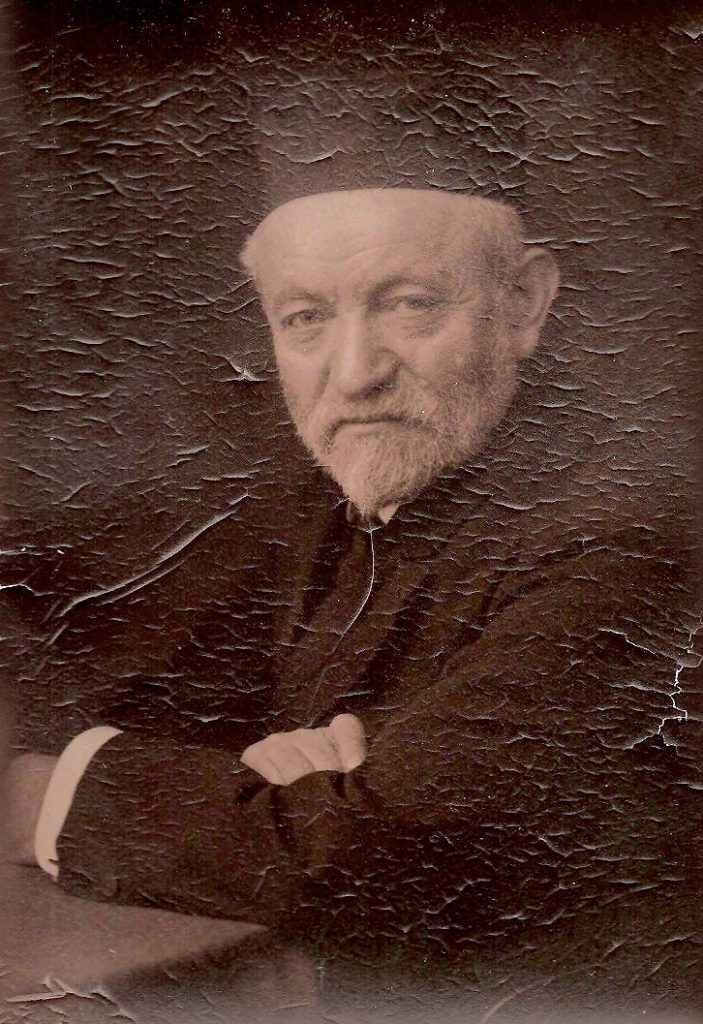

The waves of migration from eastern Europe did not simply ebb and flow. Orchestrated by the entrepreneurial spirit of the likes of Sender Jarmulowsky, they created surges of capital. The trade in ship tickets changed individual fortunes as well as permanently altering the face of both Europe and the U.S. – but not quite as Jarmulowsky had hoped

On August 30, 1914, a riot erupted on the corner of Orchard and Canal Streets on New York’s Lower East Side. The fracas began outside Sender Jarmulowsky’s “bank,” one of the most revered businesses in the area. Two months into World War I and fearing the worst, thousands of Jews clamored to withdraw their savings. But Jarmulowsky was really more of a travel agent than a financier. He sold ship tickets, facilitating purchases by issuing modest loans and taking small deposits. As such, his business simply did not have the reserves to return all its clients’ funds at once. Enraged by their inability to access their savings, “a mob of 5,000 [demonstrated] against the bankers, the State Banking Department, and the district attorney, who, they thought, should get their money back for them” (New York Times, August 30, 1914, p. 10). Carrying Yiddish banners that proclaimed, “The 60,000 unfortunate depositors of the East Side banks demand their money!” the throngs marched to city hall, where they attacked clerks. The riot ended with nine arrests.

Temple of Capitalism

Few today recognize the name Jarmulowsky or what was the “bank”’s main branch – nicknamed “the Temple of Capitalism” – which still looms over the tenements of the Lower East Side. But in the early 20th century, according to the Yiddish press, Jarmulowsky was known to “every Jew in both the Old and New World” as a purveyor of ship tickets. The rise of Sender Jarmulowsky’s business was tied to that of mass migration, which shaped the largest voluntary demographic shift in modern Jewish history.

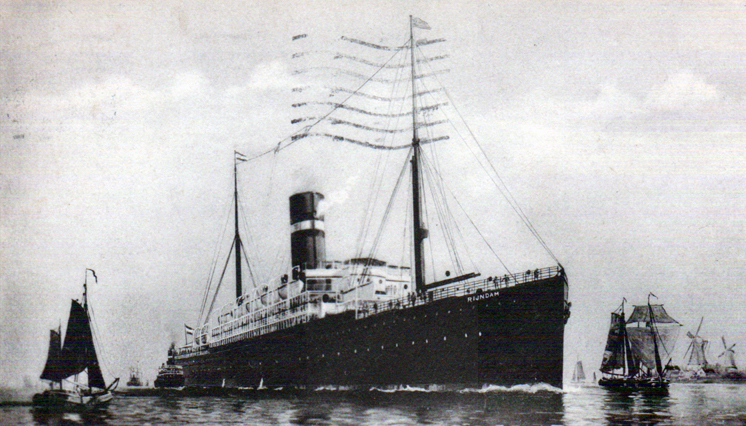

By the time the riot broke out, more than three and a half million Jews had decided to leave eastern Europe for new homes in North and South America, Europe, and Palestine. But they would have never reached their destination if not for brokers like Jarmulowsky, who cornered the market on tickets. Through his “passage and exchange offices” in New York and Hamburg, Jarmulowsky brought thousands of Jews to America. He also earned millions of dollars, using this wealth to establish important religious, cultural, and philanthropic institutions for Jewish immigrants in New York.

Many scholars have studied the migration of eastern European Jewry. Sender Jarmulowsky’s career, however, highlights a lesser-known dimension of the story: economics. Middlemen like Jarmulowsky were key players in the transnational business of migration, negotiating on behalf of the individual Jewish migrant with shipping companies and national authorities. They treated their fellow eastern European Jews as commodities, transforming not only the demographics of American Jewry but also commercial banking in the U.S.