Unlike other freedom fighters throughout history, the Judeans rebelling against Rome even minted their own coins. Why “waste” energy and resources on mere symbols of independence? What subversive messages did they convey?

The first coins were minted some two thousand six hundred years ago. Until then, people either bartered goods or exchanged them for gold or silver ingots or jewelry. Coinage made trading much easier, obviating the need to weigh the amount of metal changing hands. Coins were also potent political and cultural symbols, bearing names and often profiles of rulers as well as dates and religious or national motifs. Today they’re a valuable research resource, serving as archaeologists’ most reliable means of dating excavation sites.

Coinage originated in the kingdom of Lydia, in Asia Minor (today in western Turkey). Made of electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, these coins were placed between two metal dies and stamped by hammer and anvil. One die bore the ruler’s emblem, while the other typically featured an animal such as a lion, ram, or horse.

The innovation soon caught on in other kingdoms in the region, though in the mid-sixth century BCE electrum coins were replaced by gold and silver ones of varying weights. By then, coinage also disseminated political propaganda. Long before newspapers, they effectively transmitted governors’ messages to the public.

Handled by almost every citizen, valued currency reinforced trust in the regime. Emperors mastered the medium, using coins not only to publicize new conquests and rulers but to depict the gods.

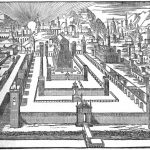

From Greece and its environs, coins spread throughout the ancient world. The Persian Empire allowed subject nations to mint their own, giving rise to the first Jewish currency – in the late fourth century BCE. Stamped with the word Yehud (as in Yehuda, Hebrew for Judah) in paleo-Hebrew script, these silver pieces served as the model for the current Israeli shekel. Owing to the biblical prohibition of graven images, Jewish coins eschewed the portraits of rulers featured on non-Jewish coinage, concentrating instead on symbols of either the Temple or local flora.

Bronze coins debuted at the beginning of the fifth century BCE, minted by city-states in Asia Minor. The seal of the local authority made these tokens worth more than their metallic weight, eventually leading to their replacement with paper money.

In the second century BCE, the Hasmonean kings of Judah minted their own bronze coins, engraving their names in the traditional paleo-Hebrew characters long since succeeded elsewhere by the Assyrian square letters used in Hebrew today. This coinage was minted by later Hasmonean monarchs whose names recall the heroic first generation – the priest Mattathias and his five sons, Yohanan (John), Simon, Judah (Maccabee), Eleazar, and Jonathan.