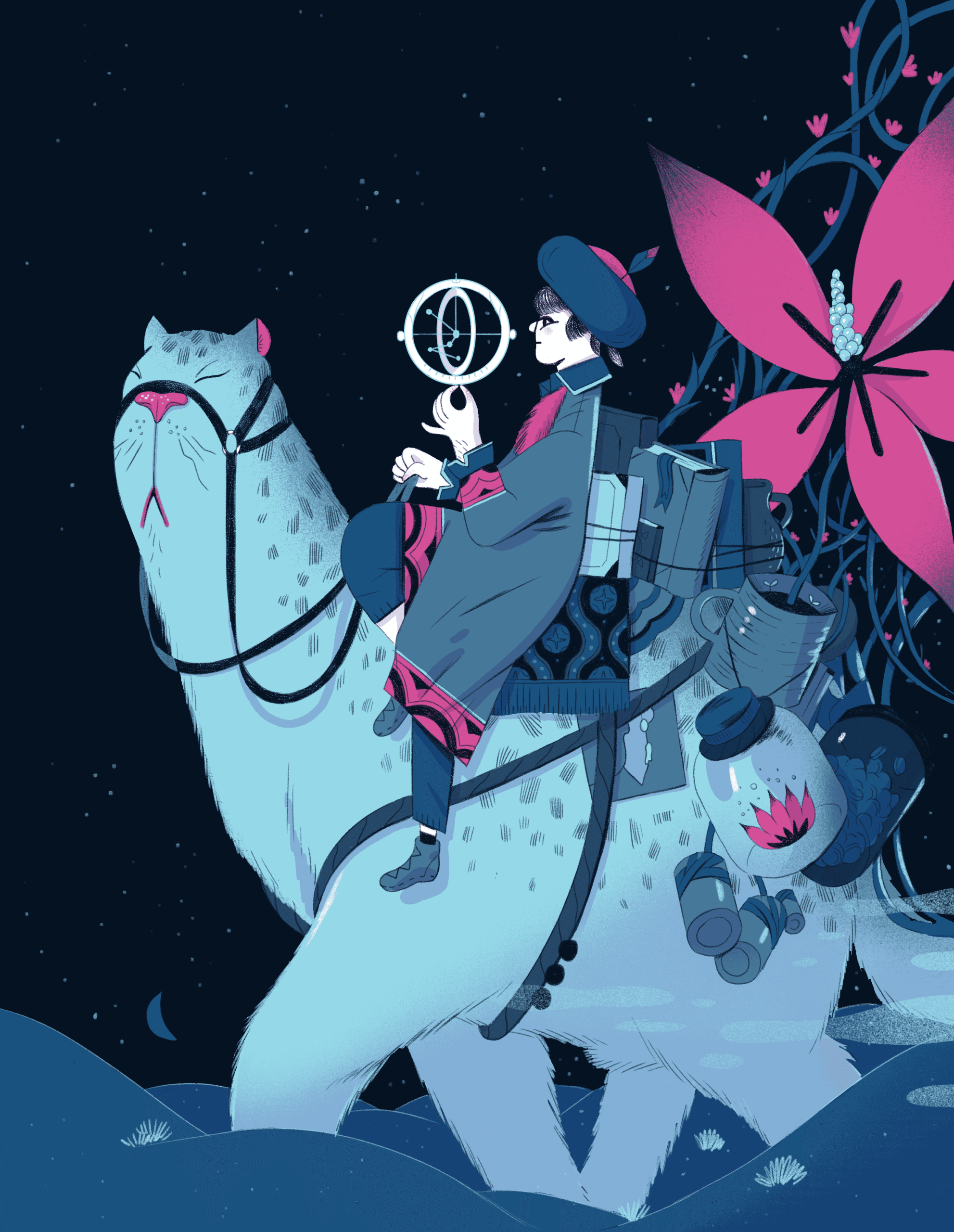

Using skills honed over generations, 14th-century scholar Ashtori Ha-parhi wandered the length and breadth of the biblical land of Israel, quadrant in hand, resolving issues that had long troubled the Jewish world

Ashtori Ha-parhi wasn’t your run-of-the mill medieval scholar. In his Kaftor Va-ferah, a sixty-chapter halakhic treatise dealing with commandments related to the land of Israel, the author went beyond the standard interpretation of Talmudic and midrashic sources and their commentaries. He actually visited the biblical locations under discussion, gaining a unique perspective on Jewish law. As Ha-parhi himself testified:

I spent two years in the Galilee, exploring and examining, and another five in the tribal lands, [during which] I didn’t lose a single hour of spying out the land. (Ashtori Ha-parhi, Kaftor Va-ferah, sec. 2 [Havazelet Publishing, 1996], p. 52 [Hebrew])

Ha-parhi was shaped by three very different regions. Born, raised, and educated in Jewish Provence, he moved to Aragon, Spain, after France subjected its Jews to the first of a series of expulsions, and finally traveled to the land of Israel, where he settled down to his life’s work of surveying it. Ha-parhi’s research was methodical and based on knowledge acquired in Provence, where his fellow Jews bridged the cultures of Christian Europe and Muslim Spain. He too facilitated cultural exchange, translating medical texts from Latin and Arabic into Hebrew.

Translation ran in his family. Ashtori was related to the Ibn Tibbon dynasty, including Jacob son of Makhir (1236–1307), one of the most prominent translators of his day and the great-grandson of the famed 12th-century author Judah ibn Tibbon, who rendered the Judeo-Arabic works of literary giants such as Judah Halevi and Solomon ibn Gabirol into Hebrew. Jacob ben Makhir was also an outstanding astronomer and mathematician whose book Quarter of Israel describes his improvements on the quadrant, a navigational tool. This metallic quarter-circle with scales along each axis represented a quarter of an astrolabe and measured angles smaller than ninety degrees between stars, allowing sailors to chart their course. Ben Makhir’s Quadrans novus, or new quadrant, had no moving parts, making it easier to manufacture and thus available to more navigators, thereby contributing to safer naval exploration.

Born of Debate

Ashtori employed this new measuring instrument to verify the borders of the land of Israel, pinpointing where the Bible’s agricultural commandments – such as tithing and the Sabbatical year – applied. This practical use of scientific advances was unheard of. Its full import can be grasped only in view of debates that racked the Jewish intellectual world while Ashtori was still in Provence.

Though Maimonides (1138–1204) had many followers there, his works (especially his Judeo-Arabic philosophical treatises) aroused significant opposition. (See “Agreeing to Disagree,” Segula 62.) In 1303, scholar Abba Mari of Montpellier, France, wrote to Rabbi Shlomo ibn Aderet (Hebrew acronym Rashba, 1235–1310) in Barcelona, denouncing the rationalist, philosophical path of Maimonides and his disciples. While reserving his sharpest barbs for the Ibn Tibbons, the critic railed against all who interpreted the Bible allegorically. In Montpellier, lamented Abba Mari, some had reduced even the revelation at Sinai to mere metaphor. Abraham and Sarah were likewise no longer real people but rather symbols, and the twelve tribes of Israel represented nothing but the zodiac.

Abba Mari requested that Rashba outlaw the study of philosophy and the use of astrology in medicine. Preferring not to interfere in Montpellier’s internal affairs, Ibn Aderet agreed to issue such a ban in Barcelona only if a similar ruling preceded it in the French town. Abba Mari attempted to fulfill this condition, but Jacob son of Makhir objected. The Ibn Tibbon dynasty was clearly a force to be reckoned with, not only in Montpellier but in the Jewish centers of Provence, Narbonne, and Perpignan.

In the end, on 9 Av, 1305, Rashba declared Greek works off limits to anyone under twenty-five except medical students. He also demanded more respect for the teachings of the sages.

The argument was cut short by the tragic expulsion of the Jews of Provence in 1306, but Ashtori Ha-parhi’s activities reveal the profound impression made by the controversy, and not just in Provence.

Child of Provence

Ashtori was born in approximately 1280 in southern France, apparently in Montpellier, although he traces his ancestors to the city of “Fleurenza, in the land of Andalusia” (Ha-parhi, Kaftor Va-ferah, vol. 3, p. 253). Hence his Hebrew last name, Ha-parhi, meaning “man of perah (flower),” or in French, “man of Fleur.” And hence the title Kaftor Va-ferach (Knob and Flower), taken from the biblical description of the menora in the Tabernacle (Exodus 25:33). (As for the author’s unique first name, see “Ashtori’s Story,” p. 31.)

Before his exile at a young age, Ashtori likely received his education – both Jewish and scientific – in Montpellier. In the 13th century, this vibrant commercial center – ruled by distant Aragon and Majorca – was relatively liberal. Its Jewish community was well integrated with its Christian neighbors and played an important role in the town’s development. The unique customs and heritage of these Jews are reflected in Ashtori’s work.

Provence stood at the crossroads between Italy and the Byzantine Empire to the east, France and Germany to the north, and Spain to the west. There was no communication between Muslim Spain and Christian Provence until the 12th century, when the Catalonians conquered the region. Provence was then exposed to the influence of Spanish Jews, many of whom fled Muslim tyranny for the safety of Christian enclaves such as Provence after the Almohades overtook much of Spain. After invading North Africa in 1148, this fanatical Muslim sect ruthlessly persecuted Jews, destroying many communities.

The steady stream of Jewish refugees who settled in Provence brought with them a rich Judeo-Arabic culture as well as scientific works in Arabic, which they soon set about translating into Hebrew for the benefit of local Jews. Yosef Kimhi and Yehuda son of Shaul ibn Tibbon both founded dynasties of translators. While the Kimhis in Narbonne specialized in philosophy, philology, and biblical interpretation, the Tibbon family passed on the lion’s share of Judeo-Arabic books from Spain. All the younger Tibbons were translators: Yehuda (1120–1190) and his son Shmuel (1160–1232) and son-in-law Yaakov Antoly (1194–1256); Moshe (1244–1283); and the aforementioned Jacob son of Makhir. Their combined efforts are considered a vital link in the “12th-century Renaissance,” which brought Arabic medical and scientific literature to Christian Europe. Ashtori’s work should also be regarded as part of this process, especially in view of the influence of his illustrious relative Jacob ben Makhir. Thanks to the Tibbon family’s efforts – which included active promotion of Maimonidean rationalism – the center of Jewish learning began shifting from Muslim Spain to Christian Provence.