As one of the Ottoman Empire’s few Mediterranean ports, Salonika welcomed Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal. Four great mystics emerged from its shores – each with a different approach to redeeming the Jewish people

In 1492, four hundred glorious years of Spanish Jewish literature and culture abruptly ended. The land that had nurtured brilliant Jewish legalists, philosophers, mystics, poets, and grammarians began to heave and tremble beneath the ancient Jewish community. Fearing for their lives and livelihoods, many converted to Christianity, emulating their leader, Rabbi Abraham Senior. But for a multitude of others who clung to their faith, the only option was to leave Spain.

Some settled in nearby Portugal, only to be forcibly baptized in 1497. Some crossed the narrow stretch of sea to North Africa, while others sought out less hostile shores on the Mediterranean, such as those of Christian Italy and Holland. Not all these Jews were welcome, as their contemporary Solomon ibn Verga wrote:

The Spanish exiles’ ships reached Italy, and there too, great famine was everywhere, and plague raged onboard. The poor souls knew not what to do […] until finally they disembarked. But the townspeople wouldn’t grant them entry. So they went to Genoa, where there was also famine, but they were allowed into the town.

Unable to abide their suffering, the young men went to the house of idolatry to convert just so they would be given a little bread. Many of the uncircumcised walked through the markets with a crucifix in one hand and a morsel of bread in the other, bidding the sons of Israel: “If you bow to this, here is bread.” In this fashion, many became apostates and intermingled with the non-Jews. (Solomon ibn Verga, Shevet Yehuda [Scepter of Judah] [Amsterdam, 1654], p. 62a [Hebrew])

But as one door closed on the Spanish exiles, another unexpectedly opened. Sultan Bayezid II, ruler of the Ottoman Empire, unlocked the gates of his realm, either in anticipation of the benefits these talented merchants could bring to his economy, or in response to pressure from Jewish leaders in Turkey. Regardless of his motives, a firman (royal edict) ordered Ottoman governors to receive all Jews kindly.

The refugees arrived penniless and sometimes – not unlike Holocaust survivors – without a clue as to what had become of their nearest and dearest. They soon viewed the Ottoman Empire as their new homeland. Nevertheless, despite their suffering at the hands of Spain’s Christian monarchs, these Jews always considered themselves Sefaradim, Spanish.

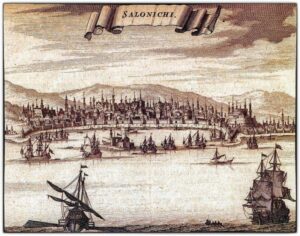

Of all their destinations, the port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki), western gateway to the empire, was unique. The cosmopolitan city was a melting pot of Turks and Greeks, Bulgars and Macedonians, Slavs, Russians, and even Frenchmen. Thousands of Jews who’d been there for generations mixed with newcomers from Germany, Italy, and North Africa. Salonika’s strategic location on the Mediterranean was also not far from Spain, making it literally a lifesaver for Spanish exiles, who could otherwise have been stranded at sea indefinitely.

Mother Salonika

A Portuguese poem by Portuguese Jewish author Samuel Usque conveys the overwhelming relief with which those lucky enough to reach Salonikan shores fell into the city’s embrace:

Behold, Salonika, you are a mother city of Israel. A faithful orchard of Jewish law and faith, filled with fair flowers and fine trees, famed for its glory among Israel. Its fruits exude beauty and majesty, for it grows alongside springs of charity, and streaming rivers of kindness and mercy water its soil. The brokenhearted and downtrodden who flee there from European lands and all other parts of the world will find healing and cure. It will absorb them lovingly, like a merciful mother, like the mother of Israel, like Jerusalem on its festivals. (Samuel Usque,

cited in Y. S. Emanuel, Leaders of Salonika in Chronological Order, part 1, p. 6 [Hebrew])

Salonika’s new inhabitants quickly made it a bustling international trading hub. Jews dealt in lead for artillery, wine, spices, and precious stones. The textile business took off, and silver and salt mines were developed. Like most Jewish centers, Salonika became a printing powerhouse as well. Many Jews grew so rich that, just thirty years after the trauma of the Spanish expulsion, Jewish ethical tracts began criticizing their luxurious lifestyle.

A tremendous spiritual renaissance accompanied the economic boom, with Salonika even becoming known as the Balkan Jerusalem. A rare concentration of kabbalists from the Iberian Peninsula gathered in the city: rabbis Yosef Taitazak, Yosef Karo, Solomon Molkho, and Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz. All four endeavored to redeem the Jewish people through various but interrelated methods. What were these paths, and to what extent did they leave a mark on Jewish history?

Practical Kabbala

The eldest of the group was Rabbi Yosef Taitazak, born circa 1465 in Castile. This Portuguese Jewish leader headed Salonika’s largest Talmudic academy. In many ways, Taitazak was the preeminent halakhic authority after the expulsion, certainly as far as the scattered Andalusian communities were concerned. Aside from being a rabbinical judge and preacher, however, he was a philosopher versed in the writings of Thomas Aquinas and many other thinkers. Yosef Karo called him “sage in all matters” (Avkat Rokhel 51).