Teaser: The Jews who dominated Thessaloniki’s garment industry celebrated Hanukka by displaying their best wares – and by ensuring the community’s schoolboys were well clothed for winter. This worthy example spread far and wide

Charity has changed a lot over the centuries. As Jews evolved from an agrarian society, biblical commandments regarding gleaning, forgotten sheaves, and unharvested corners gave way to soup kitchens and charity boxes. More recently, cash donations have largely been replaced by credit card transactions over the phone and crowdfunding via the internet. Only in widescale emergencies, from natural disasters to war, does aid take concrete form in food and clothing. Yet that’s exactly when charity finds its most authentic, biblical expression:

Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and to take the wretched poor into your home; when you see the naked, clothe them, and not to ignore your own kin? (Isaiah 58:7)

From the 16th century onward, clothing needy students was a particular focus of the Jewish community of Smyrna (Izmir), Turkey. Early in the morning on the Sabbath of Hanukka, the synagogue was already jam-packed, and its walls decorated with colorful clothing. Just before dawn, the cantor sang a poem composed for the occasion: :

I will open my mouth with song and with the expression of clear speech /

In honor of the meritorious deed of Clothing, more precious than pearls, / The lucid commandment of God. (Rabbi Hayyim Pallache, Tzedaka Le-hayyim [Charity for Life] [Smyrna, 1873], p. 46)

Subsequent verses described the roles played by various community members on this Sabbath: rabbis, cantors who composed and performed the odes, donors, schoolteachers, and – above all – young Torah students. The synagogue (or cal, as it was known in Ladino parlance, from kahal, the Hebrew word for congregation) reverberated with hymns, some composed specifically for the annual Shabbat Halbasha, Clothing Sabbath.

The rabbi ascended the podium in his richly embroidered ceremonial robe. His sermon was the height of the festivities, and according to Hayyim Pallache, Smyrna’s chief rabbi in the mid-19th century, this Sabbath was the one time he preached before the Torah reading rather than afterward. The rabbi also addressed the community in the afternoon. As Hanukka always falls in the dead of winter, when Sabbath afternoons are short, this bonus discourse meant that no one had time for a rest on that festive Shabbat.

Clothing Sabbath’s sermons filled dozens of books published by rabbinic authors all over the Ottoman Empire. Apparently introduced by Spanish exiles arriving in Thessaloniki, this custom had clearly caught on.

As early as the 15th century, there were Malbish Arumim societies – named for the daily blessing praising God as “He who clothes the naked” – which collected fabric and other alms for the poor in Spanish cities like Zaragoza and Guadalajara. Those who fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape the Inquisition set up similar institutions in their new communities. A children’s clothing charity was established in Amsterdam in 1639, and in 1828 the Portuguese Jewish community in Hamburg founded its own Malbish Arumim organization. Other such efforts were common in European cities like Venice, Prague, and Berlin. Yet Shabbat Halbasha was different: a clothing drive specifically for Torah students, it was celebrated on the same Sabbath every year.

Apparel on Display

In Jewish Thessaloniki, this form of charity was unique.

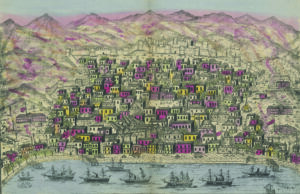

The refugees who had found shelter in the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the Spanish expulsion had arrived in the city penniless. They developed the textile industry into a global emporium. Thousands of Jews spun, dyed, wove, and sewed wool and silks, and their products were renowned the world over. Jewish cloth merchants and tailors also supplied the discerning local market and even the sultan’s court and the most senior officers in the Ottoman army.

The industry was so central to Thessaloniki’s Jewish community that its rabbis regulated fleece prices, exports of raw materials, dye ingredients, etc. This communal legislation, known as haskamot (agreements), was generally formulated in Hebrew, though some examples were written in the local Ladino dialect. One such rabbinic dictate, penned in 1555, provides fascinating testimony regarding Clothing Shabbat procedures:

[…] the income from the garment display customarily held on the Sabbath of Hanukka to clothe the poor and orphan youth has been steadily dropping, for two reasons:

- Other synagogues also hold a fashion show, and their members do not come [to the Talmud Torah] on the Sabbath of Hanukka to see the festivities.

- Various fundraisers are held in homes and courtyards.

Therefore we, the undersigned, decree that on the Sabbath of Hanukka, which is the day of the clothing display for the central Talmud Torah institute, it shall be forbidden for any [other] synagogue in our city to hold a fashion show. Should any group wish to have a clothing display in some synagogue, it must be held on a different day. (Itshak Rafael Molho and Avraham Amarillio, “A Collection of Thessaloniki Haskamot in Ladino,” Sefunot 2 [1958], p. 32)

This document contains the first known mention of a charitable clothing display, which by the mid-16th century was apparently no novelty and less lucrative than it had been.

Communal Effort

After the Hanukka fashion show – begun perhaps as advertising for Thessaloniki’s thriving textile market – the garments were distributed among needy students, giving the day its designated name: Shabbat Halbasha – Clothing Sabbath. In view of this business sector’s dominance in the city, and given that no similar custom appears in rabbinical writings from Spain or Portugal, it would seem that the practice developed in the 16th century, after the 1492 expulsion.

Thessaloniki’s Talmud Torah, whose poorer pupils benefitted from this largesse, was an umbrella organization funded by the Jewish community. The school employed numerous teachers, and much of its student body paid no tuition. Over the years, the Talmud Torah incorporated a hospital, asylum, hostel, and printing press, and even a factory manufacturing army uniforms for the sultan. The Talmud Torah awarded stipends to indigent pupils and met all their needs, including clothing. A haskama from 1595 stipulated who was eligible to receive the garb from Clothing Shabbat:

The clothing regularly handed out to needy students on the Sabbath of Hanukka should be distributed only among pupils who began their studies in the Talmud Torah from Rosh Hashana [and continued] until Hanukka. Obviously, this [restriction] applies only to city residents; if [a student] came from elsewhere, even if he joined the Talmud Torah after Rosh Hashana, he must be provided with clothes. (ibid., pp. 40–41)

The same regulation also issued guidelines concerning equality and uniformity:

The clothing given to impoverished pupils must be pre-cut and pre-sewn, in order that they not exchange [it] for superior merchandise, because all the poor students must be dressed in the same way. (ibid.)

Even the all-important sermon for Clothing Shabbat was subject to certain rules:

Similarly, for various reasons, we decree that on the Shabbat of Hanukka, any [other] clothing sermon is forbidden. (ibid.)

Apparently the goal of the prohibition was to ensure that everyone attended the sermon and saw the clothing display. This way, that Sabbath was dedicated solely to fundraising for the Talmud Torah.

As stated, the buildings belonging to the Talmud Torah served various communal functions, and any revenue from these sources was set aside for the Shabbat of Hanukka:

Income from Talmud Torah buildings must be used to buy wool, indigo, and further materials needed for the manufacture of apparel for Clothing [Shabbat] as well as additional expenditures connected to the Sabbath of Hanukka – and not for any other expenses. (ibid.)

A communal regulation from 1608 referred to a warehouse earmarked for the fabrics to be used to sew clothing for Shabbat Halbasha:

We, the undersigned, governors of the central Talmud Torah, have entered into the following agreements: To build […] a storage facility to house everything necessary for the manufacture of garments to be distributed on the Sabbath of Hanukka to the students of the Talmud Torah, including the materials for clothing, the shoes, the woolen fabrics, the scarves, the shirts, and whatever else is needed to make the clothes. (ibid., p. 44)

Income from production of Ottoman army uniforms was the Talmud Torah’s mainstay. Ottoman soldier with textile merchant, circa 1870 | Photo: Wellcome Collection

The city’s thriving international textile market depended on Jewish manufacturers and merchants. Jewish fabric vendor in Thessaloniki, late 19th century | Photo: CAP/Getty Images