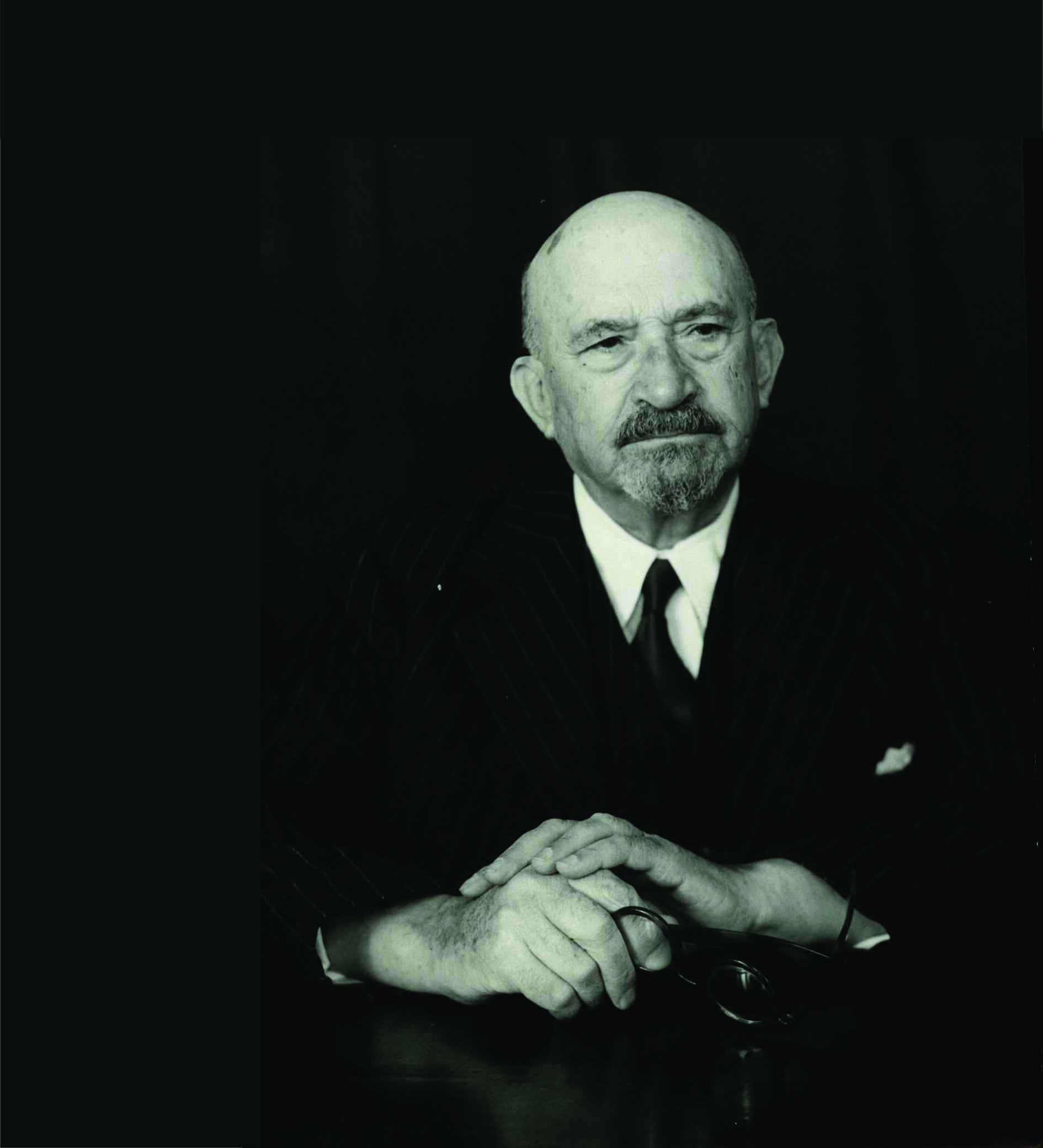

When requesting that Chaim Weizmann become Israel’s first president, Ben-Gurion described him as having done more to create the state than anyone else. Yet Weizmann’s new role effectively removed the lifelong activist from Israeli politics

Early in 1906, British electoral candidate Arthur James Balfour asked to meet one of the Jews who’d opposed the Uganda Proposal, submitted by Theodor Herzl and Balfour’s own government to the Zionist Congress. A leading Jewish Conservative introduced him to Chaim Weizmann, an up-and-coming chemist and political activist in his thirties. Having arrived in England only two years previously, Weizmann still struggled with English; nonetheless, what was supposed to be a fifteen-minute chat lasted more than an hour. Years later, Balfour described it as the moment that made him a Zionist. Had Moses been there when the sixth Zionist Congress voted for Uganda, Weizmann told the earl excitedly, the prophet would surely have broken the tablets once again.

Then suddenly I said: “Mr. Balfour, supposing I were to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?’’ He sat up, looked at me, and answered: ‘‘But, Dr. Weizmann, we have London.” “That is true,” I said. “But we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh.”

[…] Shortly before I withdrew, Balfour said: “It is curious. The Jews I meet are quite different.” I answered: “Mr. Balfour, you meet the wrong kind of Jews.” (Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error: The Autobiography of Chaim Weizmann [Harper and Brothers, 1949], pp. 110–1)

Talmudic Chemistry

Chaim Weizmann was born on November 11, 1874 (8 Kislev 5635) in Motol, an isolated, impoverished White Russian shtetl within the Jewish Pale of Settlement. (The town’s Jews affectionately dubbed it Motele.) Chaim was the third of fifteen siblings, three of whom died in childhood. His father, Ozer, made a relatively comfortable living as a lumber merchant. Quiet and gentle, he spent hours poring over Jewish and other texts. His wife Rachel’s life revolved around her children, and she was the family’s emotional mainstay. Despite the Weizmanns’ commitment to Jewish tradition, intellectual curiosity and openness pervaded their home along with Zionism and Hebrew. Chaim claimed he always wrote to his father in that language, apart from a single letter in Yiddish, which was returned to sender.

Chaim attended heder, studying under a series of strict, narrow-minded teachers. The only one he remembered fondly had Enlightenment leanings, which led him to teach Bible, Hebrew, and some arithmetic alongside the traditional Jewish fare. This instructor also exposed young Chaim to his first chemistry book:

How this treasure fell into his hands I do not know, but without ever having seen a chemical laboratory, and with the complete ignorance of natural science which was characteristic of the Russian ghetto Jew, unable therefore to understand one scientific paragraph of the book, he gloated over it and displayed it to his favorite pupils. He would even lend it to one or another of us to read in the evenings. And sometimes – a proceeding not without risk, for discovery would have entailed immediate dismissal from his post – he would have us read with him some pages which seemed to him to be of special interest. (ibid., pp. 5–6)

At eleven, recognized as a prodigy, Chaim became the first in his shtetl to attend high school in Pinsk. He reassured his worried grandfather that he’d avoid all the temptations of the big city and never write on the Sabbath – a promise he ultimately failed to keep. Amid new intellectual and cultural challenges, two areas drew him and would do so all his life: chemistry and Zionism. The Hibbat Zion movement had been founded just three years earlier, and he soon sent his former teacher in Motol the equivalent of a Zionist manifesto:

The obligation rests upon us to establish a place to which we can flee for help […]. Let us carry our banner to Zion and return to our first mother upon whose knee[s] we were born […]. For why should we look to the Kings of Europe for compassion that they should take pity on us and give us a resting place? […] In conclusion, to Zion! – Jews – to Zion! Let us go.

(Jehuda Reinhartz, Chaim Weizmann: The Making of a Zionist Leader [Oxford University Press, 1985], p. 14)

Salt of the Earth

At eighteen, Weizmann enrolled in Germany’s Darmstadt Polytechnic School. German order and cleanliness initially overwhelmed him. No less shocking was the assimilation among the country’s Jews, which he attributed to a foolish self-satisfaction and anticipation of antisemitism’s imminent demise. Well aware of German society’s lurking – and increasing – Judeophobia, Weizmann was wary of accolades, noting almost prophetically:

I do not consider it a compliment to be called ‘the salt of the earth.’ […] The role of salt […] is to salt somebody’s soup. Salt has still another quality. It can be taken only in a definite concentration. The moment the solution is oversaturated, down go the salt and the soup. (Norman Rose, Chaim Weizmann: A Biography [Penguin Books, 1989], pp. 33–4)

Chaim left this backwater as soon as possible and – after a spell in Berlin – relocated to Switzerland, completing a doctorate at the University of Fribourg in 1899. That same year, he sold one of his inventions to a large German chemical concern, and the resultant profits (followed by revenues from subsequent discoveries) freed Weizmann of financial worries for the next few years. Shortly afterward, he won a lectureship in chemistry at the University of Geneva. His future as a scientist seemed assured.

Meanwhile, Weizmann pursued a passion for Zionism. Reunions with his family, which had moved to Pinsk, were ideologically charged. Young people across the political spectrum gathered in the Weizmann home: Zionists and assimilationists, socialists and anarchists. Mrs. Weizmann even hid her children’s reading material for fear of surprise visits from the police. Nevertheless, she joked that if Shmuel the revolutionary was right, she’d live happily ever after in Russia; if Chaim the Zionist won out, she’d follow him to the land of Israel. As Chaim pointed out in his later memoirs, his mother chose Haifa, where she lived to a ripe old age surrounded by dozens of descendants.

Loyal Opponent

Weizmann lectured widely in Jewish communities in western Europe and Russia, winning souls and raising money for the Zionist cause with his dynamic oratory.

When Herzl’s The Jewish State was published in 1896, Chaim was stunned that an educated, assimilated central European Jew was preaching the Zionist gospel. Although impressed with the author’s organizational abilities, daring, clarity, and energy, Weizmann disliked Herzl’s bombastic tendencies and the personality cult that developed around him. Chaim also sensed a certain naivety in Herzl’s insistence that the Jewish people’s problems could be solved simply by engaging the goodwill of leading imperial statesmen and a few Jewish philanthropists. Like Hovevei Zion chairman Ahad Ha’am, a close friend and mentor, Weizmann identified a lack of spiritual and cultural depth in Herzl’s diplomatic Zionism.