This article was published in issue 54 | Tishrei 5781 | September 2020

One of the most famous of all Hasidic tales must be that of the illiterate boy whose sincere but unorthodox outburst shattered the sacred soundscape of Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year. Multiple versions of this story have been told and retold since its original publication in a collection of Hasidic legends by Rabbi Yaakov Margaliyot in 1896.

According to Margaliyot, these tales were of impeccable pedigree: he had heard them from ancestors who’d had personal encounters with the Besht, Rabbi Israel Ba’al Shem Tov (ca. 1700–1760; the name may be translated as “good master of the name” denoting a healer and amulet-maker);), the towering figure who inspired the Hasidic movement.

,

The Boy with the Flute

The following is an English rendition of the tale, reworked with literary license:

David saw the men all about him raise their little books, and read out of them in praying, singing voices.

He saw his father do as the other men did. Then David pulled at his father’s arm.

“Father,” he said, “I too want to sing. I have my flute in my pocket. I’ll take it out, and sing.” […]

Prevented by his father from desecrating the holy day, the boy holds out until the day is almost over.

The boy could hold back his desire no longer. He seized the flute from his father’s hand, set it to his mouth, and began to play his music.

A silence of terror fell upon the congregation. Aghast, they looked upon the boy; their backs cringed, as if they waited instantly for the walls to fall upon them.

But a flood of joy came over the countenance of Rabbi Israel. He raised his spread palms over the boy David.

“The cloud is pierced and broken!” cried the Master of the Name, “and evil is scattered from over the face of the earth!” (Meyer Levin, “The Boy’s Song,” The Golden Mountain [New York, 1932], pp. 132–4)

Different versions of the story include varying degrees of antinomianism; to compensate for his inability to pray, the boy may whistle or recite the names of the letters. The hero also ranges from the Besht himself (in Margaliyot’s rendering) to the boy (in the English account).

In Margaliyot’s tale, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov reframes the boy’s act as an outburst of inner spirituality; without the Besht’s intervention, the boy appears to have desecrated the holy day. But instead of rebuking him, the Hasidic master

acknowledges that his own spiritual endeavors can be assisted by others’ heartfelt efforts. “The Merciful One desires the heart,” he declares.

This statement is the climax of the tale. The words are a rabbinic idiom, linking the Besht to Jewish tradition despite his lauding an antinomian act. The story essentially recalibrates the spirit/law conundrum: God desires the heart rather than the law.

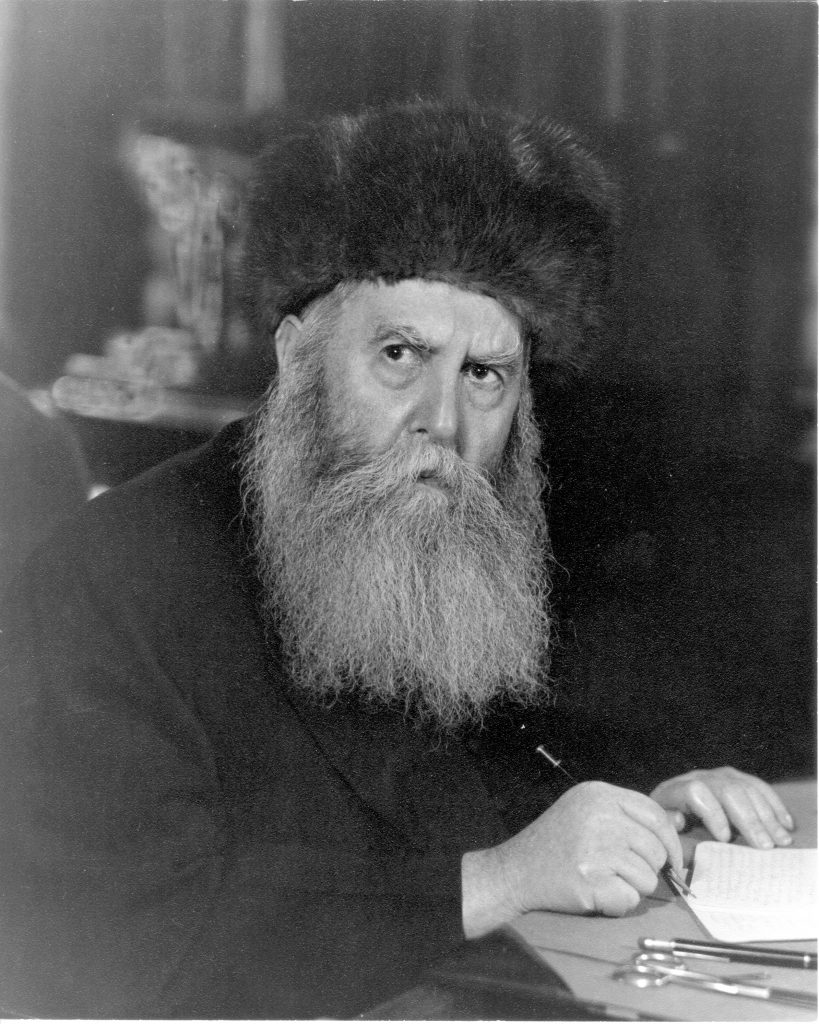

Less radical is the rendition of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn of Lubavitch (“Rayatz”; 1880–1950). To appreciate the subtle changes introduced in Rayatz’s account, some knowledge of his career and the challenges he faced is helpful.

,

Man on the Move

Rayatz was born in Lyubavichi, in the Russian Empire – seat of the Lubavitch branch of Chabad Hasidism since 1813. He was the only child of Shterna Sarah (1858–1942) and Rabbi Shalom Dovber (“Rashab”; 1860–1920), who became the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe.

In 1897, seventeen-year-old Yosef Yitzchak married his second cousin, sixteen-year-old Nechama Dina Schneersohn (1881–1971) of the Nizhyn branch of Chabad Hasidism. The marriage thus united two Chabad branches.

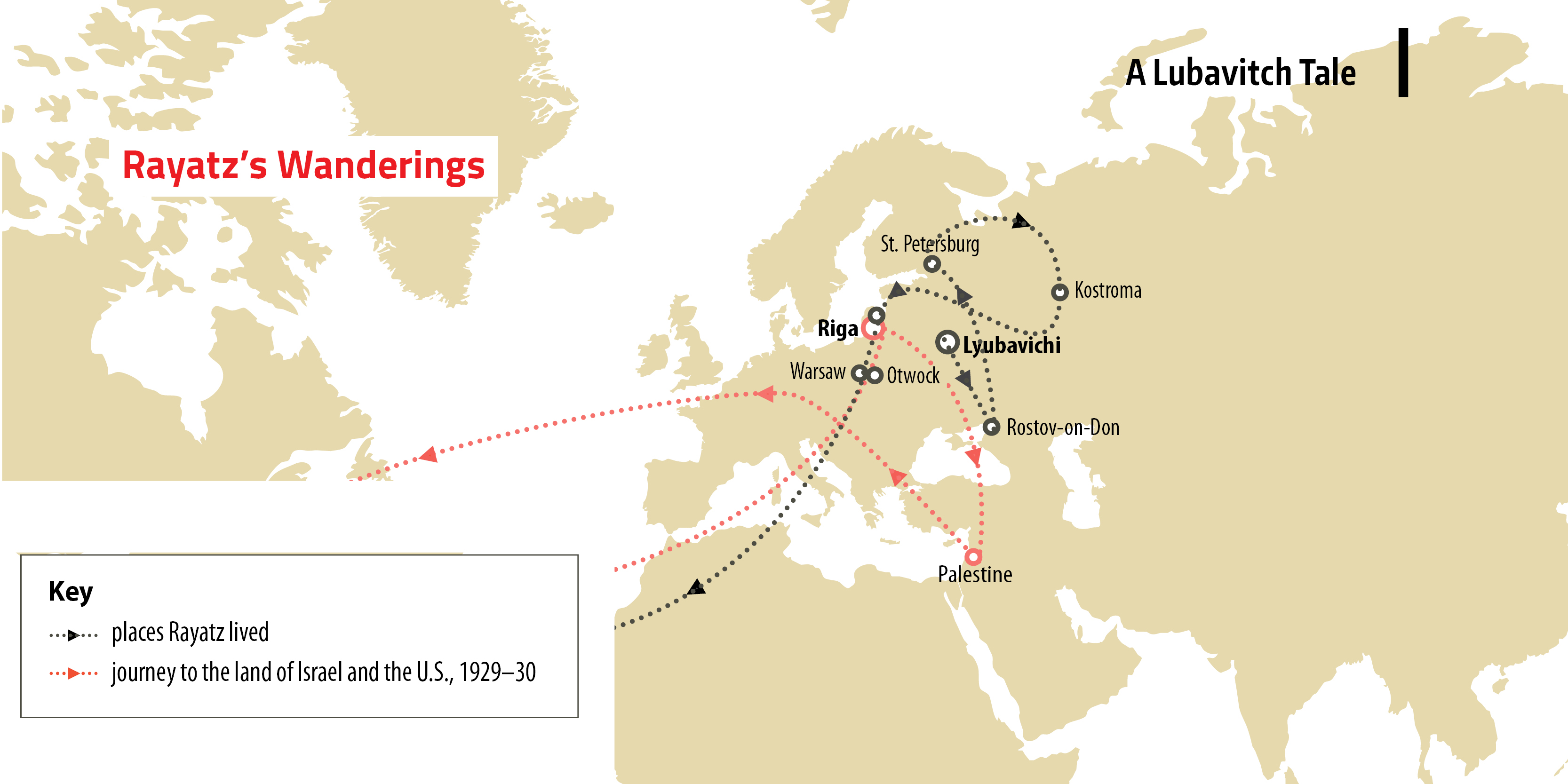

For much of his adult life, Rayatz was on the move. During the First World War, the Eastern Front advanced into Lyubavichi region. To avoid the horrors of war, Rashab and family fled 1,200 kilometers southeast to Rostov-on-Don, ending a century of Hasidic life based in Lyubavichi. Rashab passed away five years later, in 1920, and Rayatz took over Lubavitch Hasidism.

With the rise of Communism, Rayatz was hounded by Yevsektsiya – the Jewish section of the Soviet Communist Party. In its efforts to bring the revolution to the Jewish masses, Yevsektsiya strove to obliterate traditional Judaism (as well as modern Zionism). Rayatz actively opposed Communism and worked tirelessly to preserve Jewish life.

In 1924, driven from Rostov, Rayatz moved to Leningrad (today’s St. Petersburg). In 1927, he was arrested for counterrevolutionary activities. Initially sentenced to death, Rayatz was exiled to Kostroma instead. Thanks to political pressure, he was soon allowed to leave Russia. Crossing the border into Latvia, he settled in Riga..

After a year or so in Riga, Rayatz traveled to Palestine, where he was welcomed by the Chief Rabbinate and various rabbinic personalities. The Lubavitch leader visited holy sites in Jerusalem, the Galilee, and Hebron. In a Yiddish letter written later that year to his daughter Sheina (murdered in Treblinka in 1942), he movingly described his experience at the Western Wall:

For those few hours – I was alive! I forgot everything else. I was a cubit higher. I tasted moments of life! After that – everything else is mundane. Other moments will be seen, but not like those. (Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 2, p. 206)

Rayatz spent two weeks in the Holy Land. The day after he boarded a train for Egypt, the Arab riots of 1929 broke out in Palestine.

,

,

The American Chapter

Upon reaching Europe, rather than returning home to Riga, Rayatz set out for the United States. When he landed on the shores of America, the Jewish press hailed his arrival:

Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Jewish leaders have joined in a committee to honor Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneursohn, Chassidic leader of Riga, Latvia, formerly of Soviet Russia, known as the Lubavitscher Rebbe, who is now on a visit to this country. (“To Honor Famous Chassidic Rabbi Tonight,” Jewish Daily Bulletin, October 28, 1929, p. 3)

This American sojourn lasted nearly a year. Despite suggestions that he stay in the U.S., Rayatz declined. He disdained the watered-down Judaism of “the land of the free,” where even rabbis shaved their beards! Nevertheless the press reported:

His admirers in this country have asked him to remain here, and according to reports this week, it is possible that the Rebbe may soon return to this country to make his home here. (“Lubawitscher Rebbe Sails for Home as Thousands See Him Off,” Jewish Daily Bulletin, July 18, 1930, p. 4)

In July 1930, Rayatz set sail for Riga. Latvia was no Hasidic stronghold, however, so in 1934 he relocated to Warsaw – home to many Hasidic communities, including a Lubavitch yeshiva founded in 1921. Two years later, Rayatz moved to Otwock, some twenty kilometers outside the Polish capital.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, the U.S. government and American Jewish leaders – assisted on the ground by German soldiers of Jewish descent – secured passage for Rayatz from occupied Poland, via Berlin, to Riga and on to New York.

Stepping off the boat on March 19, 1940, Rayatz famously declared, “America is nit andersh” (America is no different), then set about resurrecting his Hasidic court on foreign soil. During his final decade – despite deteriorating health – Rayatz led Lubavitch Hasidism from his home at 770 Eastern Parkway, in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights district.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak’s constant movement during the interwar years may have hampered his ability to establish a large following and certainly precluded the creation of a Hasidic center. By the time he was greeted at the wharf in New York Harbor as the Hasidic master of Lubavitch, he hadn’t lived in that town for twenty-five years: “Lubavitch” was more of a nostalgic reminder of a sacred past than a location ; more of an affiliation than a pilgrimage site. This transcendence of place may have contributed to what would become a virtual Chabad community spread far and wide, with members linked by the Lubavitch “brand” fashioned in Crown Heights.

Rayatz had seen his father send disciples to distant Jewish communities within the Russian Empire – to the Mountain Jews in the eastern and northern Caucasus and to Jewish enclaves in Georgia. Building on this model, he expanded the reach of Lubavitch even farther afield.

In the 1940s, Rayatz dispatched six Russian Lubavitchers to fortify Chabad in Melbourne, Australia. And in late 1948, just two weeks after their wedding, Rayatz posted young Rabbi Zalman Posner (1927–2014) and his wife, Risya, to Nashville, Tennessee.

,

Rayatz and the Cockadoodle

Returning to our Hasidic story, Rayatz’s version, published in late 1945, offers its own unique narrative. Embedded in a treatise positioning Hasidic thought as the bridge between Judaism’s hidden lore and revealed law, the “well-known story,” as he termed it, illustrates Hasidism’s democratization of the religious experience. Even Chabad, known for its intellectual approach, explains lofty ideas with examples and parables understood by all. Despite the depth of its teachings, Hasidism stirs the emotions, engaging both mind and heart.

It happened in the days of our master the Besht, his soul in Eden, that there was a [Heavenly] accusation calling for annihilation – may the Merciful One save us – of one of the communities. And when our master the Besht saw the gravity of the situation, he multiplied his supplications on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. (Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn, Torat Ha-hasidut [New York, 1957], pp. 5–6)

As the end of the holiest day draws nigh, the knot of disciples surrounding Rabbi Israel Ba’al Shem Tov sees him redoubling his efforts. Understanding the urgency of his appeals, they too burst into tears. The congregation follows suit:

In the men’s section and the women’s section […] the men and women wept from the depths of their hearts […]. And there was a great din. (ibid.)

At this point, Rayatz changes the timbre of the tale:

For some years, a young Jewish villager, a shepherd of sheep and cattle, would come to the synagogue of our master the Besht for the Days of Awe. Since he was a total ignoramus, he would stand, listen, and watch the prayer leader’s face without saying a word. […]

And when he saw the great emotion in the synagogue and heard the weeping in the men’s sanctuary and in the women’s section, and the terrifying cries – behold, his heart too was broken inside him. And he called out in a mighty voice: “Cock-a-doodle-doo! May God have mercy!” (ibid.)

After describing the electric effect of this episode in the synagogue, the tale turns back to Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov. He hastens toward the conclusion of the service and then, beaming, breaks into song:

With a special tune, our master the Besht began the leader’s repetition of the Ne’ila prayer. And with special enthusiasm, he uttered the verses of [God’s] unity – “Hear O Israel, Blessed is the name, The Lord is God.” And our master the Besht sang songs of joy. (ibid.)

Only later that evening did the Ba’al Shem Tov explain that the great accusation that had been warded off had been personally focused,

[…] concerning the efforts he’d made to settle Jews in villages and at crossroads, where they were liable to learn from their [non-Jewish] neighbors, Heaven forfend. (ibid.)

From these charges, the simple village boy’s crowing had delivered both the community and its leader.

,

Guilty Conscience?

Rayatz’s version is richer than the original, and a close reading reveals some surprising additions.

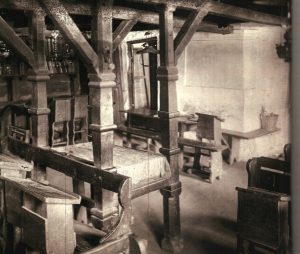

No other rendition mentions women. The reconstructed synagogue identified with the Besht in Medzhybizh doesn’t even have a women’s section.

Another twist is the “songs of joy” sung by the Ba’al Shem Tov at the conclusion of the service. While some communities end Yom Kippur with singing, it is not standard practice.

The personal accusation directed at the Besht is also out of place: though the Ba’al Shem Tov himself frequently wandered, he is not associated with sending others to “villages and crossroads.”

Who, then, is the pseudo-Besht at the center of Rayatz’s tale? Who noticed women coming to pray, sang songs of joy at the end of Yom Kippur, and dispatched emissaries to distant locales?

A clue lies in the final paragraph, in which the narrator shifts from third person to first:

I saw that the situation was very dire and that I was in a bad state. […] and the accusations against the community and myself were cancelled. (ibid.)

Rayatz recognized the place of women in Hasidism. It was in his Crown Heights headquarters that Yom Kippur ended with the victorious “Napoleon’s March.” And it was Rayatz who sent emissaries to the farthest reaches of the globe, conceivably fearing for his messengers’ spiritual well-being.

To be sure, Chabad’s contemporary universal scope must be credited to Rayatz’s son-in-law and successor, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (Ramash; 1902–1994). Yet Ramash was following in his predecessor’s footsteps. Evidence of this continuity can be drawn from the Lubavitch presence in North Africa.

Shortly before his death, Rayatz urged support for the Moroccan Jewish community. According to one account, Rayatz exhorted:

Go to the Jews of Morocco who need teachers and instructors, and disseminate Torah among them! There are no distinctions amongst the Children of Israel, whether Ashkenazim or Sephardim. We’re all children of Isaac and Jacob, and we have one God in heaven and one Torah on earth. (Rabbi Shmuel Elazar Heilperin, Sefer Ha-tze’etza’im [Jerusalem, 1980], p. 229)

Ten days after Rayatz passed away, Ramash wrote to Rabbi Michael Lipsker (1907–1985) conveying his father-in-law’s express instruction to dispatch Lipsker to Morocco. Rayatz had died before putting pen to paper, and Ramash was not yet the powerful leader he would become, so in 1950 all he could do was request that Lipsker honor Rayatz’s request (Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Iggerot, vol. 3, pp. 237–8) – which the rabbi did.

Ramash subsequently sent more emissaries, establishing a Chabad presence in various cities in Morocco and Tunisia. This network expanded exponentially, creating the worldwide Chabad-Lubavitch presence so visible today.