Though nostalgically associated with Israel’s early days, the hora was originally neither socialist nor Jewish. So how did this folk dance become synonymous with young Zionists circling under a starry sky?

There was no road to Dalia [a kibbutz in northern Israel] then. There wasn’t enough transportation either. Nonetheless, over two hundred folk-dancing enthusiasts from all over the country managed to attend the event there. They came with their tents, food, Primus burners, flags, and signs. They set up a dance center and spent two days and nights dancing and singing.

There was a mass rondo dance on the kibbutz grounds. There were demonstrations of various dances. Participants taught each other the steps they didn’t know. On the last night, we held a performance on an open-air stage beneath the central pergola.

Despite the transportation issues, an audience of three and a half thousand people came from near and far – including the Negev and the Galilee. The excitement was ubiquitous. Everyone lucky enough to be there said it was an unforgettable event. It was almost like creation. (Gurit Kadman, Am Roked [Dancing Nation], pp. 12–13 [Hebrew])

The first dance festival in pre-state Israel was held at Kibbutz Dalia in 1944. Initiated by the Kibbutz Movement’s Music Committee, the gala soon became a tradition that made folk dancing almost synonymous with the State of Israel. Festivals were held in Dalia every few years, until 1968. Most of the harvest, barn, and grape-pressing dances were choreographed to inspire a wholesome new Israeli folk culture based on the agricultural cycle of the kibbutz.

Fake Folk Traditions?

That first festival saw the founding of the Kibbutz Movement’s Folk Dance Committee, which later became the Folk Dance Department of the Histadrut labor union. Government-funded for fifty years, the department died a natural death at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

In 1947, even before the establishment of the State, the National Council (the Jewish population’s autonomous governing body during the British Mandate) sent an “Israeli” dance troupe to a youth festival in Prague. That was the first of many folk-dancing delegations tasked with bringing Israel’s youthful hope and energy to the world.

By the time Israel won second prize in the 1982 Eurovision song contest with Avi Toledano singing Hora! Even then, folk dancing had become far less representative of Israeli culture. Yet it’s still alive and kicking today. Karmiel, in the Golan Heights, now hosts the dance festival instead of Kibbutz Dalia, and Israeli folk dancing continues to attract thousands, mostly in Israel and America.

But is it really folk dance?

In 1958, Dan Ben Amotz reviewed that year’s dance festival in Dalia. Genuine farm dances, he claimed, were the inspired gyrations of hungry laborers praying for rain, whereas the festival performances were artistic creations masquerading as folk art:

I’m not suggesting that kibbutz members have to starve through a drought to enable us to say we finally have our own farmers like everyone else. But guys, at least don’t perform a “harvest dance” composed for you by some choreographer in Tel Aviv – and paid for by the Histadrut’s Center for Education and Culture – and try to pass yourselves off as farmers. And for God’s sake, don’t call the resultant infantile composition a “folk dance”! (“The Big Lie Known as Israeli Folk Dances,” Maariv, July 18, 1958)

Ben Amotz even quipped that the routines should be renamed “The Jewish Agency Dance,” “The Government Subsidy Dance,” etc.

Nevertheless, the role of dance in early Israeli history shouldn’t be ignored. Though choreographers such as Baruch Agadati, Gurit Kadman, and Sarah Levi-Tanai all played their part from the 1920s onward, exuberant displays of spontaneous dancing are etched into the Israeli consciousness as well. Most famously, with the breaking news of the United Nations vote in favor of partition and a Jewish state in 1947, thousands poured into the streets of Tel Aviv and danced until dawn. Their dancing made history on its own. Yet it originated in the Carpathian Mountains and the Balkans, in the dances of peasant farmers and Hasidic Jewry. Israel’s pioneers planted these dances deep in the soil of their new homeland, until the art form came to symbolize Zionism itself.

Secular Rebbe

The few pioneers of the second wave of Zionist immigration (1904–14) were young idealists intent on working as manual laborers in the small Jewish agricultural colonies in Ottoman Palestine. During their first Sukkot holiday in the Holy Land, a few visited Jerusalem, as had the Jewish pilgrims of Temple times.

When the festival began, our group set out for the synagogue. That evening, before our pitiful meal, we bought a some necessities with our few pennies, then went up to the roof of the house where we were staying in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Beit Yisrael. We gave the honor of reciting the festive blessing over the wine to the eldest among us, A. D. Gordon; [his blessing] echoed as far as the Mishkenot Yisrael housing project in Me’a She’arim. Then a fervent hora broke out, and the whole neighborhood gathered round.

The next day we went to synagogue again, and that day too ended with a hora. As we were dancing, with crowds pressing in on us, an elderly man with a white beard suddenly appeared. He called out to me from the circle of dancers and, with tears in his eyes, murmured in Yiddish: “Listen, my son; I’ve heard we’ve been blessed with Jewish youngsters who’ve come to Jerusalem for the festival. Do me a favor, then: stop and drink a le-haim (“to life!”) toast with me.” I stopped the dancing at once, and we all drank a le-haim with the dear old man, who never stopped excitedly muttering, “It’s the messianic era!” (Ya’akov Pinhasi, “In the Rishon Lezion Winery,” in The Second Aliya, ed. Bracha Habas [1947], p. 188 [Hebrew])

Ironically, these secular pioneers adopted the same traditional Jewish circle dances performed amid the schnapps at the end of a festive synagogue service. The elderly, ultra-Orthodox Jerusalemite described Gordon and co. as “messianic,” but he identified with their spirit not because it was new, but because it was old. The group of young socialists rallying around a charismatic leader drew directly on the Hasidic tradition these immigrants left behind.

Already fifty when he came to Ottoman Palestine, Gordon was a father figure to the much younger pioneers. Early Zionist memoirs frequently depict him ringed by dancers. As Yosef Aharonovich, who edited the socialist newspaper Ha-poel Ha-tza’ir, wrote:

His dancing was more religious devotion than gaiety; a kind of celestial joy, to use a Hasidic term. Yet his sad expression didn’t disappear when he danced. If anything, it became more pronounced with every motion and gesture. The word freylich (Yiddish: glad) was always on his lips in those days; he’d say it with a snap of the fingers, clapping, or putting his entire frame into the dance steps […], and that freylich used to escape him as if it had first been dipped forty times in a sea of despair. (Muki Tzur, You’re Not Alone in Heaven: The Correspondence of A. D. Gordon, p. 239 [Hebrew])

Gordon’s daughter, Yael, recounted how the nocturnal gatherings in her father’s yard in Ein Ganim (near Petah Tikva) inevitably ended with an emotionally charged hora, performed with almost Hasidic fervor:

If that’s how it was on weekdays, then Sabbaths were even more so. Almost everyone from Ein Ganim used to come, and other workers too, as well as some who weren’t manual laborers. There’d be a pause in the fierce ideological arguments, the singing grew louder, and then they’d move from singing to dancing, a mighty, all-embracing hora, under the heavens […]. And they never dispersed before the wee hours of the morning.

I particularly remember one Sabbath. The members of the Hadera commune came, the night before they went to settle Umm Juni – six men and two women. They looked amazing – fresh, flowing with energy [and] a childlike gaiety. The divine presence shone from their faces. And when it came to a hora, none could match the members of the commune! (“Sufferings of Settlement by One of the First,” in The Second Aliya, p. 544, [Hebrew])

To the Tune of “The Internationale”

Another figure often characterized as the inspiration for dancing, particularly during the third wave of Zionist immigration (1919–24), was author Yosef Haim Brenner. Not only was Brenner much older than most of his fellow pioneers when he came to the Holy Land in 1909 at age twenty-eight, he was already a celebrity. Historian Anita Shapira describes him among the crowds celebrating the founding of the Histadrut Ha-ovdim (a labor union combining various socialist parties) at a Hanukka convention in Haifa in December 1920:

The dancers bore Brenner aloft until he begged to be put down. In exchange they demanded that he go onstage and address them, and he agreed. His talk revolved around the first verse of Psalm 133, “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity,” and they danced all night to its melody. He made a connection between “for brethren to dwell together in unity” and “Workers of the world, unite,” the slogan of the Socialist International, contending that the two slogans were one, and then spoke about the history of the unification […]. (Anita Shapira, Yosef Haim Brenner: A Life, trans. Anthony Berris [Stanford University Press, 2014], p. 338)

Brenner explained that the emphasis on brothers dwelling “together” in the biblical verse meant that sometimes even brothers could get along.

A member of the Labor Brigade (Gedud Ha-avoda, forerunner of today’s United Kibbutz Movement) also recalled an encounter with Brenner. The occasion was the dedication of a wooden hut that was to house the idealists who’d chosen manual labor as their way of uniting Zionism with socialism. Brenner made a profound impression:

Brenner was on the podium. His wide face radiated nobility. He didn’t lecture; he delivered a sermon.

“A harp hung above [King] David’s bed, and a northern wind came at midnight, stirring the strings so it played by itself […]. The people of Israel came to him and said, ‘Your people need money.’ ‘Go make a living from one another,’ he told them. ‘The cistern can’t fill itself,’ they answered. ‘So stretch out your hands to the brigade!’” he said […].

Here [Brenner] raised his voice and cried: “Stretch out your hands – make them straight. Gone is the hour of [soft hands]; now we need hands outstretched to work. And where? In the brigade!”

After the meal, the evening passed in boisterous singing and dancing. The walls were soon too narrow to hold the dancers, and they poured outside; the dancing broke out anew in the spacious courtyard. And Brenner slipped away. (K. Barlev, “With Brenner and the Labor Brigade,” in The Third Aliya, ed. Yehuda Erez, vol. 1, p. 329 [Hebrew])

Reworking a Talmudic legend about King David, Brenner captivated his audience, rejecting bourgeois values and the “soft hands” of romantic ballads. In his rendering, hands outstretched in battle become hands hard at work in the Labor Brigade.

Again, how ironic that this secular pioneer had retained the passionate commitment and Talmudic intellectualism of traditional Judaism – and with them, the dance, sweeping the listeners to their feet and binding them in a euphoric circle.

From the founding of a settlement to the completion of the threshing, Zionist milestones were often marked with dancing. The camaraderie of the third Sabbath meal, as dusk faded into nightfall, often spilled over into dancing. But then, so could any meal; chairs and tables would be moved aside as hands joined and voices rose in song.

In a Word | HORA

The word “hora” comes from the Greek chorea (dance), as does “choreography.” This etymology reflects Greek influence on the dialects spoken in the Balkans and the Carpathian Mountains, where the dance originated. Baruch Agadati, one of Israel’s first choreographers, created what he called the Galilean ora, from the Hebrew word meaning “awaken.” This term never caught on, though; the hora defied translation, and Agadati’s dance routine became known simply as Agadati’s Hora.

Defying Despair

The hora was also an antidote to despair, an act of defiance against all odds. As such, it came to embody the pioneer spirit, as we find in Hebrew poet Yitzhak Lamdan’s most influential work, the oft reprinted Masada (1926). Based on the heroic suicide of Masada’s Jewish defenders as described in Josephus’ Wars of the Jews (published in Hebrew just a few years earlier), the poem transposed the land of Israel, last refuge of European Jewry, onto Masada, the last outpost of Jewish rebellion against the besieging Roman army.

The third section of Masada is dedicated to nocturnal bonfires and dances. “As the air, heavy with heroism, infused the limbs with joy […], night bonfires leapt up on the walls, / and the men of Masada broke out in frenzied dance around them” (Yitzhak Lamdan, Masada [1927], p. 35 [Hebrew]). These circle dances signified both continuity – recalling the Hasidic dances of the previous generation – and rebellion:

The dance of Masada ignites

And burns –

Move aside, fate of generations

Take care […]Stumbling feet are once more lifted

Never mind!

Weep not for beheaded yesterdays,

Tomorrow’s ours! (Lamdan, pp. 39–41)

Throwing themselves into the dance, the pioneers found respite from hardship and hopelessness. It was almost an act of worship, a symbol of struggle. “Go on, dancing in the chain!” this section of the poem concludes. “Masada shall not fall again!” (ibid., p. 42). The latter declaration has since been uttered by every new recruit swearing allegiance to the Israel Defense Forces, many of whose induction ceremonies traditionally took place at Masada. The same words echoed on the lips of countless children in Jewish youth movements. Masada even inspired plans for a last-ditch defense of Palestine’s Jewish communities against the Germans in World War II (see “Palestine’s Final Fortress,” Segula 36). Like Masada, the hora became a symbol.

Hymn of the Hora

Lamdan turned the hora into a Zionist emblem. The stories of Brenner and Gordon encircled by dancers were retold in the context created by Masada and gained new significance. The resulting consciousness is particularly evident in the words sung along with the hora dances from the 1930s onward, after Lamdan’s poema had become engrained in popular imagination.

Before the publication of Masada, the hora was danced to wordless Russian or Polish folk tunes or Hasidic melodies. Hasidic Jews sometimes chanted excerpts from the Bible or liturgy as they spun, some of which were adopted by the pioneers. Examples include Hinei ma tov u-ma naim (“Behold, how good and how pleasant,” see above),Ve-taher libenu le-ovdekha be-emet (“Purify our hearts to truly serve You”), and Od avinu hai (“Our father still lives!” [paraphrasing Genesis 45:3]).

Sometimes these lyrics expressed longing for redemption – shared by the pioneers, though their vision was of course different. And sometimes the latter reworded a traditional song: “Blessed be our God, who made us in His honor,” for instance, became “Blessed be our God, who made us pioneers.” Songs from the first wave of Zionist immigration in the 1890s remained popular too.

But after Lamdan penned his poem, lyrics were written not just for the hora, but about it, even in praise of it. Zelig Posek’s “Ode to the Hora” is a perfect example:

Hora, hora, you’re my all

You melt away the beggar’s angst;

My hora banishes sickness,

Holier than any saint.I have a tiny homeland

Which I hold so very dear

All I own is the shirt on my back

A flame eternal sears my heart.Hora, hora, set me afire

’Til death am I betrothed to you.

(Mizmor La-hora, www.zemereshet.co.il [Hebrew])

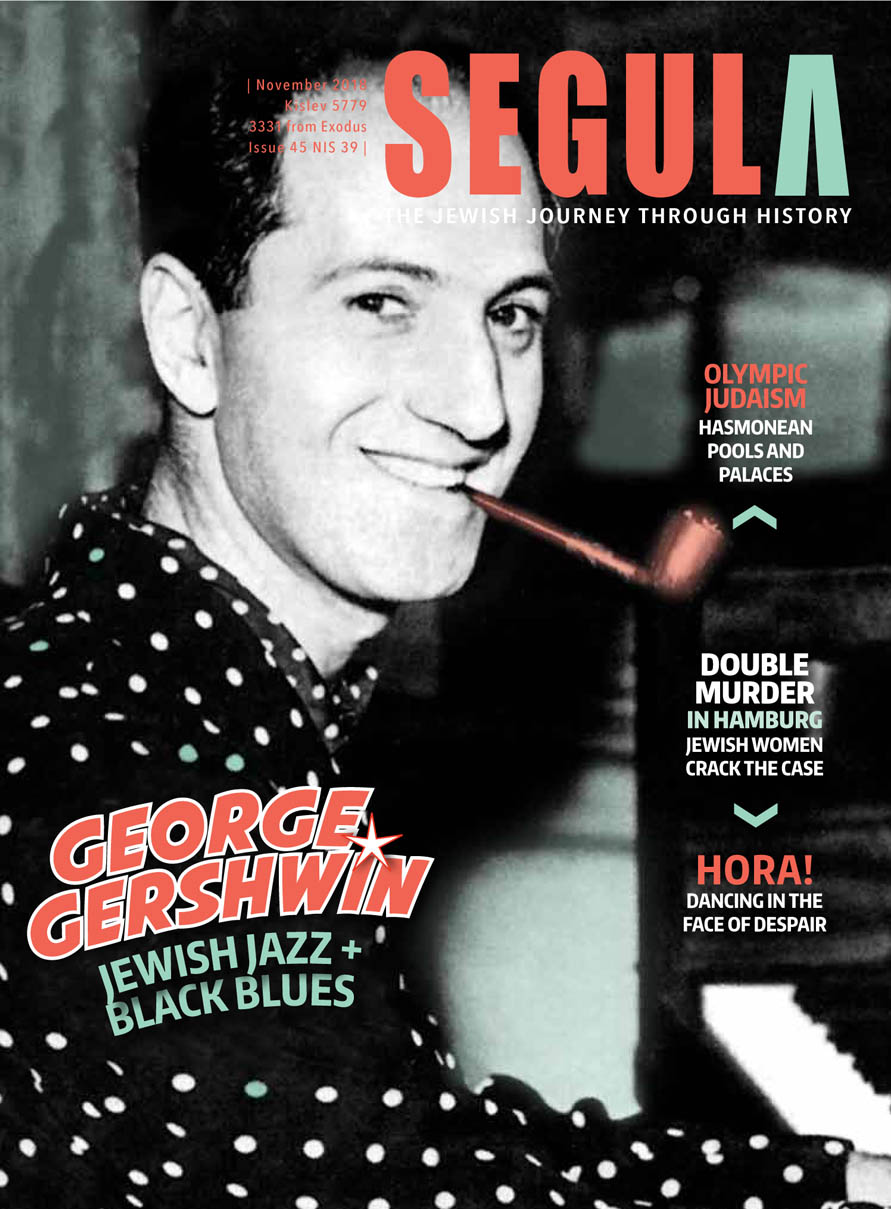

Masada made the hora into a Zionist icon. Yitzhak Lamdan with one of the many editions of his epic poem

If the hora was the Zionist equivalent of a mitzva, the lyrics were the blessing traditionally accompanying such Jewish practices. Despite all the hardship, the dancers gave themselves over to the frenzy of the moment. Yael Gordon’s memoirs describe the festivities marking the Hadera commune’s first night on the land it had received:

I remember it well: just when the dancing reached its highest pitch, they noticed that Yosef Beretz was feverish with malaria. They urged him to leave the circle and lie down, but all their pleas were in vain: “I’ll dance until I work up a good sweat and the fever passes,” he said. “I can get a dose of quinine in the morning.” (The Second Aliya, p. 544)

Cut off from their families both geographically and ideologically, the lonely pioneers found comfort as well as companionship in the close-knit circle of the hora.

A pioneer, a pioneer am I,

A forerunner shepherding the wind

No shoes, no clothes,

Not even a pickled herring.I don’t know where I came from,

I seek no grand affairs,

In work, out of work,

But never in despair.My family’s forgotten,

Moishe, Hannah, Dvoira,

My sisters and my brethren

Are those who dance the hora!(Aaron Ze’ev Ben Yishai, Halutz Hineni [A Pioneer Am I], www.zemereshet.co.il [Hebrew])

The circle represented a society of equals linked by dance. Yesterday they may have been strangers, but now the hora united them. Like Lamdan’s Masada, the hora was no promise of success, but a cry of defiant despair, a struggle against all odds. That’s why one hora song was called “Hora Come What May”:

Though the heart aches,

Though the pain sears,

Burn them away with the “Hora Come What May!”

Our blood, stormy as a surging sea

Our land, a land left desolate

Our mind, disturbed and dreaming

Our hora, our only solace.(Hillel Avihanan Bergman, “Hora Ein Davar,”www.zemereshet.co.il [Hebrew])

Nostalgic Beginnings

Though the hora remained an Israeli institution for generations, the pioneer spirit and charged atmosphere originally surrounding it soon became history. Hora lyrics written in the 1930s were already nostalgic. In 1933, a gifted twenty-three-year-old from Tel Aviv put his own words to the rhythm of the dance. Nathan Alterman, soon to become the state’s founding poet laureate, wrote:

Such a wonder, such a wonder,

That such nights can ever linger,

That one can still attempt to

Dance a hora such as this!Hora, awaken! Awaken, O hora!

Once we start, it can’t be stopped!

[…]

We’ll remember, yet remember,

Melodies of Mother Hora

I’ll recall your every part,Mother of my heart! (Nathan Alterman, Eizeh Pele, www.zemereshet.co.il)

But the hora is more than just a legacy. Songwriters continue calling for its revival, dreaming of bringing back not just the hora, but the bittersweet yearning of Israel’s pioneer days:

Potent the night, potent our song,

Piercing right up into heaven,

Turn again, turn to us, hora,

Fresh and multiplied by seven.(Ya’akov Orland, Hora Mehudeshet [Hora Renewed], www.zemereshet.co.il [Hebrew])