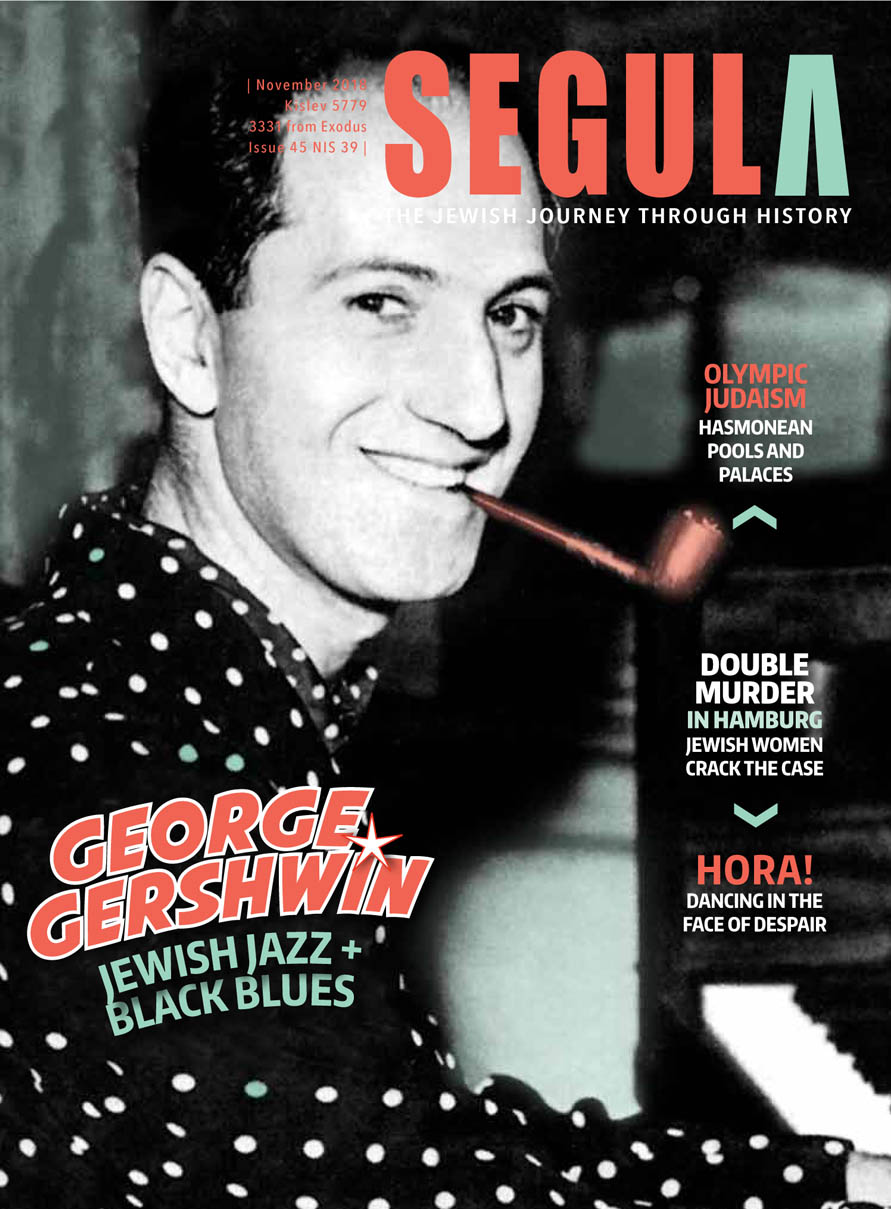

The cultural meld of Jews and blacks working together in show business gave rise to a new style of American music. Captivated by black sounds and rhythms, composer George Gershwin interwove classical motifs and popular melodies into a black and white razzmatazz of jazz

Though American music has long been defined in terms of black or white, depending on itscommunity of origin, there are also shades of gray. Nineteenth-century Irish composers gave American popular music lilt, and Italian singers have also made their mark. It took a while for these ethnic influences to penetrate America’s WASP elite, but from the 1880s onward, Jews were vastly overrepresented in the emerging music industry.

Today we take the vocal virtuosity of black divas, the wail of the blues,and the ecstasy of gospel for granted, but the music must have grated on the conservative ears of white America after the Civil War. Overall, American music is largely the product of black-Jewish collaboration, a cultural blend manifest in the struggle for civil rights as well.

As Europe’s Jews fled the slaughter engulfing them, Jewish Americans were creating a new musical genre. If German composer Richard Wagner had attributed the mediocrity of 19th-century music to its many Jewish contributors, then the Jews’ reinvention of American music was their revenge. They wrote the popular ragtime melodies, the hit Broadway musicals, the movie soundtracks, the groundbreaking jazz operas, and the folk and blues of the civil rights movement. Their music projected the America they dreamed of: liberal, multicultural, cosmopolitan; a land of opportunity for all, regardless of race, creed, or gender. To quote Ira Gershwin, they “built a stairway to paradise.”

Black Like Me

“Uptown Funk” (2014) has been one of this decade’s biggest hits. Recorded by Jewish producer Mark Ronson and vocalist Bruno Mars, who also has Jewish roots, the single is full of black slang. Though it sounds like updated 1970s funk, the song typifies an aspiration shared by white pop music composers and performing artists over the last century – to be, as author Norman Mailer titled his famous essay on American society, “White Negros.” The timbre of black vocals, the Afro-American beat, and the aura of “black cool” represent the ideal.

Pop music reflects a kind of inverted racism: “black” is considered the real deal, while “white” is just a wannabe. Jewish musicians played an important part in promoting this perspective; as composers and performers, they built the American music industry on the foundations of black musical culture.

Jews ventured into show business first and foremost as entrepreneurs. All six of Hollywood’s major movie studios were famously founded by first- or second- generation Jewish immigrants. But Jews were just as involved in the music industry. Music was neither particularly profitable nor respectable in the 19th century, attracting little investment and interest. But as vaudeville gained popularity in New York during the 1880s, and copyright became law in the 1890s, conditions were ripe for songwriters to rake it in. Suddenly, with one hit, lyricists and composers could be set for life – and make a profit for their music label too.

Land of Opportunity

From 1880 to 1920, over two and a half million Jews disembarked on America’s East Coast. Most settled in the urban centers, especially New York, where they formed the city’s largest ethnic minority, peaking at just under a third of the population in 1925 (see “A Community in Flux,” Segula 11). Though the United States was paradise compared to the seething anti-Semitism of Europe, Jews weren’t welcomed everywhere. Heavy industry, Wall Street’s most prestigious firms, and the leading universities were all off limits, forcing American Jewry to find alternative avenues of advancement – niche industries just then coming into their own. One such was the garment trade, and entertainment was another. Generally speaking, Jewish immigration to the U.S. was incredibly successful, coinciding with the rise of American capitalism, which fit these newcomers like a glove. Their success may well have prompted the elites to stop mass immigration in the 1920s, raising hurdles for further potential arrivals.

American Jews, especially those of German origin, were among the pioneers of music publishing in New York, employing marketing strategies used in their previous lines of work. The music labels set up shop around Broadway, opening small companies to write, produce, and distribute songs as sheet music – the only way to get them out there before widespread use of the gramophone. Jewish journalist Monroe Rosenfeld dubbed the area “Tin Pan Alley” for the cacophony of singing and piano playing echoing from the studios. In the first half of the 20th century, the name became synonymous with American pop music.

Alley Cat

Tin Pan Alley was where George Gershwin started his career. His parents were Russian immigrants who’d married in America and changed their name from Gershowitz to Gershwin. George was born Jacob in 1898, two years after his brother Ira (Israel). Ira later became George’s partner, writing lyrics to popular songs and musicals, including parts of his trailblazing opera, Porgy and Bess. Like many other Jewish families the Gershwins struggled financially but made sure their children grew up in a secure, cultured, bourgeois environment, speaking English rather than Yiddish.

George’s biographies describe him as a hyperactive twelve-year-old street kid entranced by the piano from the moment his family acquired one. He had a natural talent, playing by ear. Though he took piano and composition lessons, his only musical higher education consisted of two courses at Columbia University. One instructor, pianist Charles Hambitzer, declared him a jazz-mad genius – and that was even before the first jazz recording came out in 1917!

Hambitzer schooled his pupil in the basics of modern classical music, but George sought inspiration elsewhere. He was influenced by the Yiddish theater, befriended pianist and composer Leslie C. Copeland, and early in 1915 detected the beginnings of jazz in the work of African- American musicians. Their Harlem Stride Piano style was similar to ragtime but looser, more complex, and harder to play.

Gershwin saw black trends as the basis of the developing American music scene. He knew which side he was on in the debate raging between conservative WASP composers and proponents of modernist multiculturalism. In many ways, the avant-garde won out, coming to dominate both classical and popular music, and embedded Afro-American elements firmly within the American musical tradition.