Stepping into the world of Shlomo Moussaieff’s antiquities collection at his home in Herzliya is more like walking into a magical Aladdin’s cave than a neatly categorized museum. His fascinating – and controversial – collection revolves around Moussaieff’s self-avowed obsession with proving the veracity of the Bible

“God is compassionate, forgiving iniquity…. Suppressing his anger;” quoting the evening prayer, Shlomo Moussaieff raised the heavy black leather strap with its three metal studs over his shoulder. “Lord, save us!” he brought it down on, thwack, on the small display table. “That’s how they would punish us at home,” he reminisced. “Or punish me, that is.” As a professed dyslexic, Moussaieff was always in trouble for not paying attention in heder. Other items, all from the Moussaieff family home in Jerusalem’s Bukharian neighborhood, crowded the dark wood surface: a pair of Purim graggers (noisemakers), the strap, and a set of sharpened slaughter knives in a black leather pouch, inset with the word “kosher” in Hebrew. Moussaieff’s father insisted the local shohet (ritual slaughterer) use his personal set of knives, sharpened in accordance with halakhic requirements, whenever he came to their house.

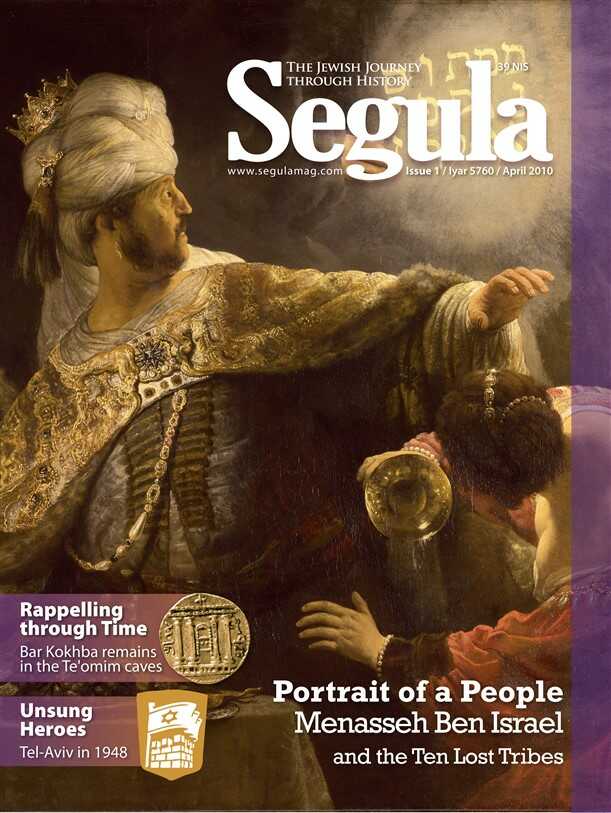

Moussaieff owns one of the largest – and most controversial – private collections of biblical antiquities in the world. Any item which can shed light on the veracity of the Biblical narrative is grist to his mill. But he is also an avid collector of Judaica with an emphasis on ancient manuscripts and personal seals. Moussaieff has used the fortune he inherited and the proceeds of his substantial jewelry business to finance what is by any standards an impressive if eclectic collection. On the walls and surfaces of the reception area of his private penthouse overlooking the sea, Babylonian and Assyrian reliefs jostle for space with the intricately carved doors of arks from Eastern Europe; menorahs and Torah scrolls push up against charity boxes and engraved silver platters. Items from every corner of the Diaspora rub shoulders in a veritable Aladdin’s cave of treasures, each in some way unique, each with its own story. “Every time I see them, I remember I’m a Jew,” says Moussaieff. The jeweler who has supplied princes and heads of state with ornaments literally fit for a king is personally guiding me around his collection, a unique opportunity reserved for Moussaieff’s friends and acquaintances. His collection of Holy Land antiquities is particularly controversial; while incontrovertibly including items of real significance, there is a strong probability that at least some of the objects are clever replicas or even fakes. Moussaieff has been known to admit he would be prepared to pay for a really outstanding imitation – if only because he would so like it to be genuine.

Moussaieff certainly has the means to acquire the genuine article. As he points out, if you wave around half a million dollars and say you’re looking for pages from the famed Aleppo Codex, there is a fair chance that whoever has them will find his way to your door. On the other hand, he most definitely raises the stakes for unscrupulous swindlers and counterfeiters. There is a strong possibility that some of the more complex techniques of replication have been developed thanks to the prices men like Shlomo are prepared to pay to corroborate details appearing in scripture. The Bible provides the details, the replicators provide what are often genuine if innocuous artifacts, an inscription is added – and the world of archeology is buzzing with news of a sensational discovery. Investment in the creation of fakes has been shown to pay off.

Even the most respected museum collections, ranging from the Louvre to the Israel Museum, have been known on occasion to include a fake or two among their antiquities, so it would hardly be surprising if here and there an item or two of dubious origin were to slip in among the genuine articles. Bar Ilan University has dealt fairly extensively with Moussaieff’s collection. David Ben Naim, the curator of the collection of kabbalistic manuscripts, the bequest of Solomon Moussaieff, Shlomo’s grandfather and the builder of Jerusalem’s Bukharan quarter, takes a skeptical view. “He’s lucky if twenty percent of his antiquities are authentic,” he estimates. On the other hand, he has no hesitation whatsoever with regard to the two hundred and twenty manuscripts in his care. The entire collection, ranging from the fifteenth century to the twentieth, has been made available on micro-film for academic research.