Exchanging the lab for the analyst’s couch, Sigmund Freud defied the scientific conventions of his day. The man who attributed supreme importance to early childhood benefitted from his own adoring Jewish mother’s assurances that he was destined for greatness

When Sigmund Freud published his magnum opus, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), he expected it to change the face of the approaching century. Just to make sure it would belong to the new century rather than the old, he asked his publisher to stamp the binding with the year 1900. The study introduced his theories of the unconscious and how to treat the psyche, insights he described as a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence. He even speculated that his home would one day bear a plaque: “Here Dr. Freud discovered the secrets of dreaming.”

Freud attached great importance to his work, and thus to himself. His dogmatic opinions were born not only of conviction, but also of a certain measure of self-doubt. During his long career, he left lists of material for his biographers, destroying whatever he preferred to be forgotten.

MAMA’S BOY

Sigismund Schlomo Freud was born in May 1856 in Freiberg, Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire. The first child of Jakob Freud and his third, much younger wife, Amalia, he subsequently changed his name to Sigmund, as Sigismund figured in too many anti-Semitic jokes. His Hebrew name (Solomon) is synonymous with wisdom, and his innate intelligence and curiosity were indeed evident from an early age. An avid reader with a quick grasp of languages, including Greek and Latin, he was frequently the top student in his class.

His family was so sure he was headed for greatness that the daily routine at home revolved around his studies. His mother called him “my golden Sigi,” smothering him with love though she had seven other children. Freud later cited his family, and especially his mother, as the source of his rock-solid self-confidence.

Like many of their contemporaries, Freud’s parents were drawn to the big city. The family moved to Vienna when he was three. Freud grew up with the liberal, scientific outlook of the intellectuals of his age, famously rejecting formal religion. Yet he identified as a Jew, albeit – as his greatest biographer, Peter Gay, called him – a godless one. At age twenty-six, Freud married Martha Bernays, granddaughter of scholar Isaac Bernays (who had mentored Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, founder of the Neo-Orthodox movement in Germany). The couple had six children. In a 1926 letter to the Italian neurologist Enrico Agostino Morselli, Freud wrote:

Though I have been far removed from my ancestors’ religion for many years, I have never lost my feeling of solidarity with my people.

Freud even attributed his independent, original thinking to the fact that as a Jew, he was automatically an outsider. Almost all his colleagues were Jewish (see Jewish Science, p. 21), and he rarely bonded with non-Jews. Even his close association with Carl Gustav Jung, a pastor’s son, was tinged with a belief that only a non-Jewish disciple could spread psychoanalysis beyond Freud’s own Jewish circle. Tribal heritage was a recurring theme in his thoughts and ideas. In a letter to Sabina Spielrein, a Jewish patient and former lover of Jung’s who herself became a psychoanalyst, he wrote:

I am, as you know, cured of the last shred of my predilection for the Aryan cause, and would like to take it that if the child turns out to be a boy [Sabina was pregnant with her first daughter at the time] he will develop into a stalwart Zionist. … We are and remain Jews. The others will only exploit us and will never understand or respect us. (Ronald Hayman, A Life of Jung [New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2001])

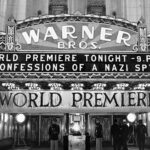

Under Hitler, Freud’s books were burned by a frenzied mob in Berlin, and Gestapo officers persecuted him and his family. Although he fled to England with his wife and children in June 1938 (aided by British scientists, American diplomats, and French princess Marie Bonaparte), four of his sisters were murdered in concentration camps. Extraordinarily, Freud was also assisted by Nazi officer Anton Sauerwald, who was influenced by his writings. Ordered to seize Freud’s property, Sauerwald falsified his own reports, allowing the Jew to escape. Sauerwald even helped his Austrian personal physician visit Freud in London. Sauerwald was arrested in Vienna in 1945, but a letter written by Freud’s daughter Anna led to his release two years later.