What led a young, acculturated Jew from Prague to seek guidance at the court of the Bełz Hasidic master? What brought this spiritual seeker back to his hometown and then to Tel Aviv? And how was that journey linked to this poet’s homosexuality? The Hasidic tale of Jiří Langer

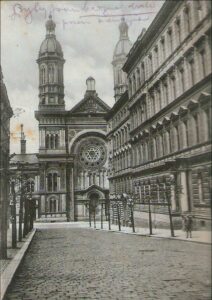

Prague is hardly a city remembered for its rich Hasidic tradition. Hasidism was never a strong presence in the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia, where German culture outweighed Yiddish. Even Hasidic tales featuring Prague are scarce. Nonetheless, one assimilated Czech Jew found lifelong inspiration in the Hasidism he encountered while searching for meaningful Jewish experience in eastern Europe, subsequently recording his adventures in the Hasidic heartland and complementing those memories with his own poetry.

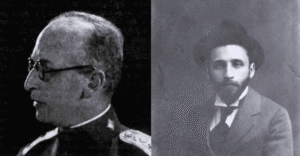

He was born in Prague in March 1894, and the name his parents gave him at his circumcision was Mordekhai Dov. But his Czech-speaking family called him Jiří (pronounced Yizhi), the Czech equivalent of George.

Outside In

At nineteen, “inspired by a secret longing,” Langer left Prague to find his Jewish roots. In his Nine Gates to the Chassidic Mysteries, published twenty-five years later, he still couldn’t explain what had precipitated the journey (Jiří Langer, Nine Gates to the Chassidic Mysteries, trans. Stephen Jolly [London, 1961], p. 3).

Langer’s family hailed from the mountain village of Ransko, near the Czech-German border. His paternal ancestors were descended from a Dutch court Jew who’d come to the region with his patron to establish an iron foundry. His mother’s family included different career paths, such as the rabbinate, medicine, and math. With the Langers’ move to the Prague suburb of Královské Vinohrady, their connection to tradition weakened. Although Jiří’s grandfather had prayed with other Jews every Sabbath in the mountains, in Prague his son had to work on Saturdays, though he promised his father not to smoke on the holy day (and was consequently particularly irritable). The Langer kitchen was kosher, but only because their devout Christian maid had previously worked for an Orthodox Jewish family.

Czech writer František Langer (1888–1965) is the main source of biographical information about his younger brother. In his introduction to Nine Gates, František noted that Judaism meant little to him and his contemporaries:

So long as anti-Semitism did not rear its head too close to us or too noisily, our generation looked upon the register of births as its only link with Jewry. (ibid., p. xiii)

Jiří, however, was different. Even as an adolescent, he was drawn to his Jewish roots and intrigued by mysticism. He began studying Hebrew and Jewish texts with a friend, Alfred Fuchs, who later became a Catholic philosopher. Langer’s path led him to Bełz , as his brother later recounted:

In 1913 my brother packed a small suitcase with a few essential clothes, some books and his phylacteries, and set out on a journey. He told no one save Julia [the family maid], to whom he confided that he was going to Galicia. (ibid., p. xvi)

Langer had no known Hasidic ancestors, but his wanderings led him to Galicia, to the Hasidic court of the charismatic Rabbi Yisakhar Dov Rokah (1851–1926) of Bełz – a city Jiří subsequently called “the Jewish Rome” (ibid., p. 4). Initially he felt like a stranger and was treated accordingly. Years later, Langer reflected on his difficulty gaining full access to the community:

It is an impassable road to the empire of the Chassidim. The traveler who pushes his way through the thick undergrowth of virgin forests, inexperienced and inadequately armed, is not more daring than the man who resolves to penetrate the world of the Chassidim, mean in appearance, even repellent in its eccentricity. […] Only a few children of the West have accomplished this journey, hardly as many […] as there are fingers on the hand that writes these lines (ibid., p. 3)

Despite these obstacles, Langer returned to Bełz a few months after his first foray. This time he stayed with Rabbi Yisakhar Dov for several years, becoming one of those few outsiders who penetrated his circle, integrating into the community by adopting Hasidic practices and attire:

[…] now that my beard and side whiskers are well grown, now that I am able to speak some Yiddish and have begun wearing a long shipits (an overcoat similar to a caftan) instead of a short coat, and ever since I have started to wear a black velvet hat on weekdays, as all the other Chassidim do, this ice-wall of mistrust has gradually begun to thaw. (ibid., p. 19)

Langer found the spiritual and emotional intensity of Hasidism irresistible. “The sight of the saint’s mystic dance fills us with godly fear” (ibid., p. 14), he wrote in his own introduction to Nine Gates. Long passages recount the ecstasy of Sabbaths and festivals with the Bełz Hasidim in the present tense, despite the decades now separating him from the experience.

Metamorphosis

With the outbreak of the Great War, Langer accompanied the Hasidic master of Bełz in his flight from the Eastern Front, finding refuge in Munkács, Hungary. All the while, though enthralled by Hasidism, Langer also felt revulsion:

I can endure it no longer. This life of isolation from the rest of the world is intolerable. I feel disgusted with this puritanism, this ignorance, this backwardness and dirt. I escape. I travel back to my parents in Prague. But not for long. I must perforce return to my Chassidim. (ibid., p. 12)

While he wanted out, Langer referred to “my Chassidim,” indicating that he considered this spiritual path and brotherhood his own. Nevertheless, he admitted that conditions in the Bełz Hasidic community were challenging:

My health is affected and I am conscious that I am becoming physically weaker every day. The daily bath before morning prayer, the bad food, the all too frequent voluntary fasts, the loss of sleep, and the lack of movement and air considerably weaken the otherwise strong constitution of a youth who is not yet physically mature. But I force myself to face up to things. I will not give in. (ibid., p. 17)