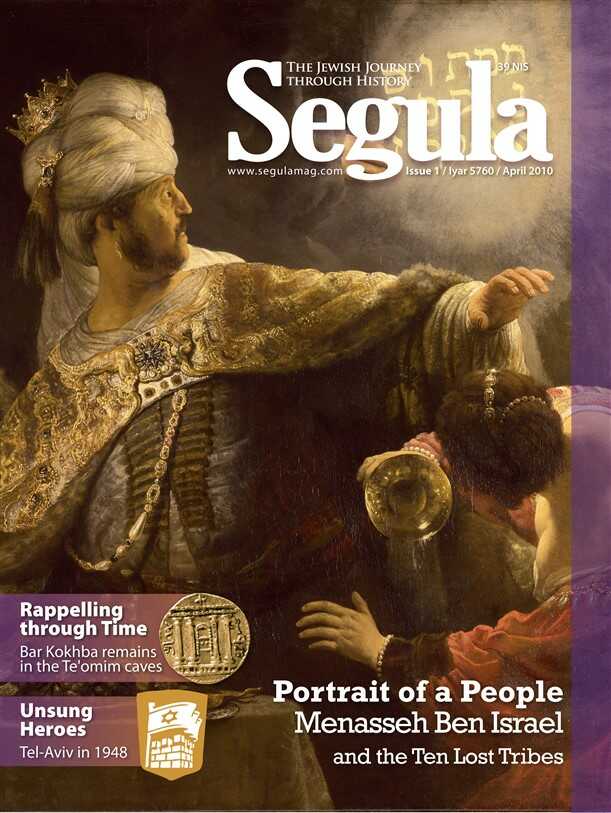

Inspired by rumors of the Lost Ten Tribes, he sought to fulfill the age-old vision of redemption by scattering his people to the very ends of the earth. Rembrandt von Rijn, Baruch Spinoza, and Oliver Cromwell, all path-breakers in the cultural reformation of Europe, held him in esteem. Although life dealt him many disappointments and his efforts often seemed to be in vain, hope was indeed a key word in the lexicon of Menasseh Ben Israel

In September 1644, an unusual traveler arrived in Amsterdam from South America. As a marrano he had been known as Antonio de Montesinos; now reclaiming his Jewish name – Aaron Levi de Montesinos – he told a strange story. During his many years traversing the Americas, he claimed to have met a group of American Indians who expressed knowledge of the Shema and were said to be descendants of the tribe of Reuben; descendants of the tribe of Joseph, they insisted, were living nearby. It was further claimed that these Indians expected to soon escape from their current environment and take part in the general redemption of Jewry.

For all this information, the traveler completed a formal affidavit in verification. For one of the dignitaries of the Amsterdam community in whose presence the affidavit was signed, the moment marked a turning point in his career. The rumored existence of the Ten Lost Tribes on the American continent would send Menasseh Ben Israel in another direction altogether – to the less remote but cloudier shores of England, in pursuit of nothing short of that same promised redemption of the Jewish people.

First Years

The Portuguese Inquisition archives state that one Manuel Dias Soeiro was a native of Madeira, having been born there in 1604. [ Map-] This island in the Atlantic Ocean was then part of the united Portuguese-Spanish Empire.

He was the son of Joseph Dias and of Gracia Soeiro, previously of Lisbon, Portugal. Their life story was typical of the tragic fate of much of Portuguese Jewry. The laws of both their country and the Holy Roman Empire had required them – as it had done their parents since the end of the fifteenth century – to renounce Judaism completely in favor of Catholicism. Their baptism resulted in their being classified officially as “New Christians,” but just as in Spain, they were popularly termed – and considered – marranos – swine! However successful the individuals might be – even if they became leaders in their professions or members of the elite classes –they were subject to constant suspicion of allegiance to Judaism, with horrific personal and family consequences on arrest by the state or church authorities.

And so it was for Joseph. On a visit to Spain, presumably as a merchant, he was for some unknown reason (if any!) accused of Jewish practices. For this he was tortured, brought to an auto-da-fe, imprisoned, and had his property confiscated. He was lucky – his “recanting” allowed him to return to his family, albeit as a lifelong cripple. It was forbidden for New Christians to lawfully leave Portugal, so he took his wife and daughter out to sea, to the dependency of Madeira, where in a short time Manoel was born, followed by another son.

Their situation was tenuous. As English Jewish historian Cecil Roth writes in his definitive work A Life of Menasseh Ben Israel (1945): “The conditions in the Spanish and Portuguese dominions continued to be perilous to a degree for the Portuguese Marranos; being indeed worse rather than better as the 17th Century advanced.” So when still an infant (after baptism!), Joseph and Garcia took him and his siblings (no doubt by stealth) to La Rochelle in Southern France. Here the family, with others in a similar position, could exercise Jewish rites in private more safely, the town being then known as a Huguenot (Protestant) center that opposed Catholicism. Outwardly, however, it was still necessary to conform to Christian observances, and the status of the town was uncertain. Therefore, when Manoel was just 6 years old he was taken by his parents to start what was to prove a new life in Amsterdam, the capital of Holland then as now.