Fifty years ago, Israelis lived and worked freely in Iran. How did those peaceful relations turn to war, and how do Iranians perceive Israel now, after half a century under the Islamic Republic?

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 was undoubtedly the turning point in modern Iranian history, redefining every aspect of Iran’s domestic and foreign policy and transforming the country overnight from Israel’s ally into its bitterest foe. Although Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons has kept it at the forefront of international concerns, the nation has remained largely a riddle in Western eyes. Given the complexity of Iranian identity, with its many layers of history, Iran’s citizens necessarily encompass a broad ideological and political spectrum.

A Threefold ID

Today’s Iran is built on three main foundations: an imperial, Persian monarchy; Shia Islam; and – as developed over the last two hundred years – modern Western culture. Every attempt to eliminate any of these three has failed. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, whose reign began in 1941, minimized the role of religion while embracing ancient Persia. At the same time, he cultivated ties with the West to modernize his country by means of science and technology. Ruhollah Khomeini overthrew the shah after the 1979 revolution, reinforcing Islamic culture and seeking to uproot Persian traditions as well as distancing Iran from Western influence. Yet the Pahlavi dynasty couldn’t weaken the martyred Imam Hussein’s mysterious hold on Shia Muslims any more than the Islamic Republic has managed to disconnect the Iranian people from the heritage of Cyrus, “king of kings” and father of the Persian Empire. Nor has the current regime distanced its citizens from Western influence.

Based on the first two building blocks, Iranians feel destined to dominate the region. Shiites have long seen themselves as an Islamic elite whose birthright of Islamic leadership – as the prophet Muhammad’s true heirs – was stolen by the Sunnis. The Islamic Revolution seemed an opportunity to right that wrong.

This revolutionary mindset transcends national boundaries, encompassing self-proclaimed victims worldwide. In the early 20th century, Syrian intellectual Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi (1854–1902) envisioned Mecca – in Arabic, Umm al-Qura, or “Mother of All Cities” – as the spiritual center of a pan-Arab, anti-Western Islamic revival, just as the city was in Muhammad’s day. Iran’s rebellious clerics borrowed from al-Kawakibi but replaced Mecca with their own country as the focus of the Islamic world.

Ayatollah Khomeini was the first to pitch Iran as Islam’s greatest bastion and defender, and his followers continued in that vein during the 1990s. The Islamic Republic of Iran is depicted as the savior of the entire Muslim world, with all Muslims thus obligated to defend the country from existential threat. Accordingly, the fall of Iran would spell the downfall of Islam as a whole.

This elitism is fortified by the Iranian people’s self-image as heir to the Persian Empire, once the greatest in the world and also the first of its size. All the territories of that vast and mighty civilization are still called “Iranian lands.” Iranians take pride in Persian culture and science as well as in having preserved their national identity despite repeated conquest. Thus, Islamic zeal and dreams of Persian world domination combine to create a potent sense of global power.

Over the last two centuries, Iran has grappled with modernity by alternately cutting itself off from the West and aping it. Despite the country’s current rejectionism, Western cultural influence there will likely not just disappear. As an aspiring international force, Iran cannot avoid adopting certain aspects of modern liberalism: nationalism (complete with parliament and constitution), education, and above all technology.

Nationalism, Islam, and the West all play their part in modern Iran. The checks and balances between them just keep changing from one regime to another.

Islamic or Iranian?

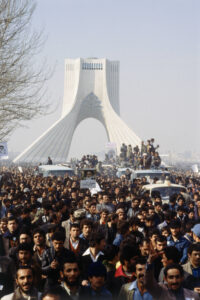

The Islamic Revolution began as a popular uprising against the shah’s authoritarian rule. Communists and Islamists alike opposed his Westernism, while other revolutionaries hoped for a more liberal, democratic regime. In the end, the Islamists won out, and Khomeini became the supreme keader. A new constitution enshrined the ayatollah as the chief Shiite cleric, whereas previous heads of state had never been part of the religious establishment. Despite a broad spectrum of Islamic opinion and observance developed over generations, Khomeini’s interpretation of Islam became the exclusive doctrine. Although he lived in exile until shortly before the shah was deposed, the ayatollah’s attitudes didn’t reflect contemporary Islamic thinking or positions of all the grand ayatollahs.

Having seized power, the revolutionaries had to maneuver between their ideals, political and economic shifts (such as the eight-year war with Iraq beginning in 1980), and Iran’s needs. National interests have generally taken precedence over ideology. In 1988, for instance, Khomeini authorized the government even to demolish mosques or suspend Islam’s primary commandments if necessary. How exactly the sometimes conflicting demands of Islam, the regime, and the supreme leader are determined, and by whom, remains ill-defined.

Revolutionary leaders have also clashed over when and to what degree idealistic principles can be overruled. Difficult but basic issues – whether and to what extent religion can be separated from the state; isolationism or engagement, particularly with the West; etc. – have all been subject to disagreement, if not public debate.

Although the shah is widely thought to have prioritized national concerns while Khomeini ignored them, the ayatollahs’ regime is in fact often nationalistic. Early in the revolution, for example, Khomeini rejected a proposition that the Persian Gulf (which other Arab countries call the Arabian Gulf) be renamed the Islamic Gulf.

In theory, the revolution was to grant equality to all ethnic and religious minorities – including Shia and Sunni. In practice, according to the Revolutionary Constitution, only an Iranian Shia Muslim can be president. This provision ruled out a leading contender in the first presidential elections after the revolution: Jalal al-din Farsi (whose last name even means “the Persian”), of Afghani extraction.

Another anomaly has been Iran’s close relations with Syria, governed until this year by the secular Ba’ath party under Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar. In contrast, although Iraq is also run by secularists, Iran’s border dispute with that nation led to an eight-year war based on its “heretical” Sunni faith.

Similarly, national and political considerations impelled Iran to align itself with Christian Armenia during hostilities between that country and Shiite Azerbaijan. Furthermore, according to strict revolutionary principles, Iran should have come to the aid of Bashar al-Assad’s persecuted subjects when a popular Islamic uprising threatened his regime. Instead, Iran shored up his rule both during the Arab Spring of 2010 and against the threat of isis (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria). In 2024, however, the ayatollahs finally let the younger Assad’s regime crumble.

Rebels replaced the shah’s statue with photos of Khomeini, Tehran, 1979 | Photo: Michel Setboun/Getty Images

Opposition to the shah united Communists, socialists, and Islamists on the Iranian streets. Armed rebels in Tehran, 1979 | Photo: Hatami, Library of Congress Collection