The Spanish expulsion is usually considered the nadir of Judeo-Christian relations on the Iberian Peninsula, but in many ways the largely overlooked mass conversion of Jews a century earlier was far worse

For much of their existence, Jews have suffered as a small minority, and in every generation there have been those who threw in their lot with the non-Jewish majority. Although some abandoned Judaism for ideological reasons, others did so in pursuit of a more comfortable life or for fear of persecution. Sometimes, perhaps even in most cases, they left for all three motives combined. Conversion and assimilation seldom appealed to enough Jews in any given community to jeopardize its very existence. One such rare case was the great wave of conversions in late nineteenth-century western Europe, following hard on the heels of modernization and secularism.

There have of course been other mass conversions in Jewish history, beginning with the exile and disappearance of the ten tribes of Israel and following the bloody Jewish revolts against Rome in the first centuries CE. Yet the baptism of almost half of Spanish Jewry in the late 1300s and early 1400s is little known.

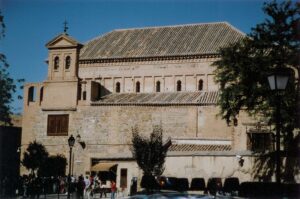

The Iberian Peninsula probably boasted the world’s largest concentration of Jews in the late Middle Ages. Estimates vary, but the global Jewish population likely numbered some one million, and about half lived in today’s Spain or Portugal, which then included the kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Navarre, Portugal, and Granada (the region’s last Muslim stronghold). Evidence of an early medieval Jewish presence lies in the numerous decrees promulgated against Jews in the last 120 years of the Visigothic Kingdom, precursor of Catholic Spain. (The Visigoths adopted Catholicism in 589.)

Immigration significantly expanded these communities after the Muslim conquest of Spain at the beginning of the eighth century. Jews remained highly visible after the Reconquista (the reestablishment of Christian rule) in the mid-13th century, which left only Granada under Islamic leadership. The Almohads – the last Muslim kingdom to dominate the region – had violently expelled anyone refusing to convert to Islam, putting all Jews to flight. As a result, Spanish Jewry at first welcomed the new Christian monarchs.

Jewish life began deteriorating after a civil war between Peter (Pedro) I, king of Castile, and his half-brother Henry (Henrique) II ravaged the area in the late 1360s. Most Jews supported Peter, who was sympathetic toward them, so when Henry gained the upper hand they feared repercussions. It was only in 1391, however, that some of the worst pogroms in Diaspora history took place, spreading like wildfire across the peninsula.

1391

As early as 1378, dynamic Ferrand Martinez, archdeacon of Ecija (near Seville), began demanding that Jews either convert or face expulsion and called for synagogues to be destroyed. Despite recurrent rebukes from John I (Juan), Henry’s successor, and instructions from the archbishop of Toledo to rein in his rhetoric, Martinez continued his incitement. Riots finally broke out in Seville on June 4 (1 Tammuz), 1391, killing many and forcing most of the remaining Jews to abandon their faith. Other towns were caught up in the violence as well, which raged for more than three months.

This chaos stemmed from a weakening of central authority after the death of John I in 1390. His son Henry III was a mere boy of eleven, leaving his ineffective guardians in charge. No significant punitive measures were taken against the rioters, so the lawlessness not only sprawled across Castile but seeped into neighboring Aragon, ruled by another John I. This king sent his brother Martin to Valencia to protect the city’s Jews, but to no avail. Hesitating to pit his soldiers against their fellow Christians, Martin failed to prevent the mob from storming the Juderia, the Jewish neighborhood. As in Seville, heavy casualties were followed by forced conversion.

To defend his incompetence, Martin cited the soaring numbers of Jewish converts as proof that their persecution was God’s will. Legend even had it that demand for baptismal waters outstripped supply, but the founts miraculously refilled each morning.

The Valencia massacres spilled over into the surrounding towns and villages, eventually reaching Barcelona, Girona, and even the Balearic Islands, off Spain’s east coast. The king of Aragon managed to protect his Jewish subjects in the royal city of Saragossa but not throughout his kingdom, being distracted by his wife’s miscarriage and its ramifications for his own succession.

By the time the rioting died down, the Jewish communities of Castile and Aragon were unrecognizable. Tens of thousands of Jews had been killed, and over two hundred thousand converted. Major Jewish enclaves such as in Seville, Cordoba, Valencia, and Barcelona had disappeared.

Though the Catholic Church had ruled against conversion under duress, forcibly converted Jews were accepted as Christians. And no Christian was permitted to embrace Judaism, so there was no way back for these conversos.

Leading rabbi Hasdai Crescas set up an underground network to help converts escape to countries where they could openly rejoin the Jewish community. Prime destinations were North Africa and the northern kingdom of Navarre. Yet most conversos stayed put and simply behaved like Christians. Although Rabbi Hasdai was safe in Saragossa, he lost his only son, who lived in Barcelona.

The Second Wave

A second wave of conversions resulted from a collaboration between church and state involving Ferdinand I of Aragon and Benedict XIII of Avignon, known as the anti-pope because his papacy was contested by a rival in Rome. Also complicit was Joshua of Lorca, Benedict’s Jewish doctor (and a rabbi!), who’d accepted Christianity and taken the name Hieronymus de Sancta Fide (Jerome of the Holy Faith).

Ferdinand’s Jewish subjects were forbidden to work as government clerks or live in city centers, and Jewish doctors couldn’t treat Christians. These decrees made conversion a tempting option. At the same time, charismatic Father Vincent Ferrer traveled across Aragon demanding that Jews either convert or suffer the consequences.

Hieronymus also persuaded the Spanish monarch to authorize a Christian-Jewish debate reminiscent of the one held in Barcelona over a century earlier, whose results had compelled Nahmanides to flee Spain. The resulting Tortosa Disputation dragged on in the town of that name for two years, starting in 1413.

Under these abysmal conditions, an estimated twenty-five thousand more Jews converted in Aragon, including the De la Caballería family of court Jews. Returning from the disputation to his native Daroca, Rabbi Yosef Albo found that almost his entire congregation had converted. This student of Rabbi Hasdai Crescas wrote his famous philosophical work, Sefer Ha-ikkarim (The Book of Essential Principles), in response to his community’s dire situation.

Although the Jews’ plight eased after Ferdinand’s death and Benedict’s replacement, the cancellation of previous decrees in no way mitigated the conversos’ predicament. Like the victims of the previous wave of conversions, they had to remain Christian – at least outwardly.