Crypto-Jews are usually associated with the conversos of early modern Spain and Portugal, but less than two hundred years ago, the Jews of Mashhad, Iran, met a similar fate. How did a century in hiding affect Jewish life in this community?

Iran has undergone not one but three Islamic conversions. The first, as Muhammad’s seventh-century heirs spread Islam across most of the ancient Near East; the second, no less dramatic but more protracted, when Iran’s ruling Safavid dynasty (which controlled the country from 1501 to 1736) made Shia rather than Sunni Islam the national religion; and the third with the fall of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Republic in 1979. The Safavids launched a campaign of persecution against all non-Shiites. Sunni Muslims, Jews, and Christians alike were viewed as a religious and social threat. Jews were publicly humiliated, subjected to indignities such as being marched through filthy, degrading spaces. In Isfahan, the Safavid capital, Jews were expelled from the main neighborhoods and transferred to marginal areas under military observation. Aspects of this policy continued under the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1794 to 1921. Fleeing pogroms in the cities of Tabriz, Shiraz, Kashan, and Yazd, Jews scattered throughout the empire.

In 1839, a mass conversion of Jews took place in the town of Mashhad, in the relatively remote northeast of the country. The Muslims called this forced conversion Allahdad – God’s Gift – but the converts secretly remained Jewish. Generally speaking, Jewish communities in Islamic lands suffered a sharp increase in persecution as well as discrimination during the 19th century. Nevertheless, the story of the crypto-Jews of Mashhad is unique.

A Jew from Tiberias arrived in Mashhad in 1884 during a three-year tour of Syria, Aram Naharayim, Iran, Afghanistan, and Bukhara, apparently seeking funding for his community. He somehow won the trust of the crypto-Jews, enabling him to describe their extensive outward precautions:

There’s a street in Mashhad, […] the Jews’ street, and today some call it mahalle jadid [street of the newly converted]. That’s where the Jews once lived. But if a Jew comes to the street today, they won’t let him set foot in their homes, lest he defile everything therein. Perhaps they also fear being libeled as secretly loving a member of their forefathers’ faith. Only with great effort could we achieve our goal of penetrating the minds and hearts of these people. (Efraim Neimark, Voyage to the Land of the East, Yaari edition [1947], p. 89 [Hebrew])

Other travelers also wrote about the crypto-Jews of Mashhad, and there’s documentation of their appeals for aid – from Heaven, from the Iranian government, and from their brethren outside Iran. Yet information about their underground existence comes mainly from memories passed down through their families. During the 1930s, Yaghoub Dilmanian and Farjullah Nasrulayoff began recording the history of the community. Their account was handed down by community members and printed only years later – with distribution restricted to family and friends.

Under the Safavids, Jews were publicly persecuted. Traveler Jean Chardin sketched this method of punishment he witnessed in 17th-century Iran | From Cavalier Chardin’s Journal of a Journey to Persia, 1686

Capital of the Safavid Empire from 1598 to 1736, Isfahan was replaced by Mashhad with the rise of the Afsharid dynasty. Royal procession en route to Isfahan, 1726 | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Jews of the Shah

Jews evidently arrived in Mashhad during the reign of Nadir Shah (1736–47) or about a decade later. Under this monarch, Iranian Jews benefitted from a brief window of religious tolerance after centuries of persecution. Nadir Shah moved the Iranian capital from Isfahan to Mashhad, partly to symbolize his break with two centuries of Shia rule. To reinforce control of the area, he transferred thousands of his subjects there, including twelve Jewish families from Qazvin. Jews from Dilman, Yazd, and Kashan eventually joined them, until the community numbered some forty families. According to community legend, the Jews were summoned to Mashhad to guard the treasures amassed by Nadir Shah during his conquests in India.

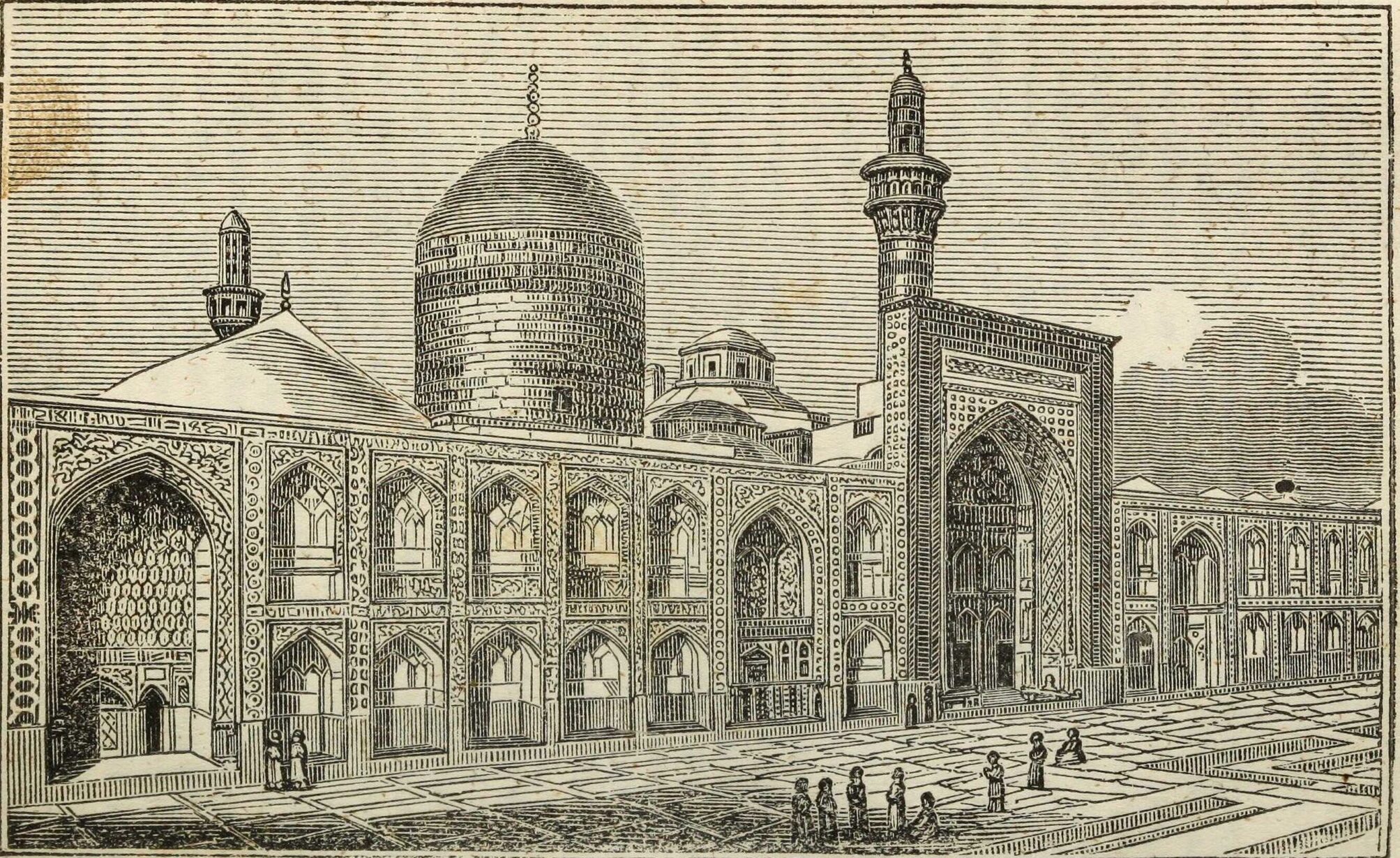

Ali al-Rida, eighth imam of the Twelver Shiite sect, was martyred near Mashhad in 818. As the burial place of Imam Reza, as he’s known in Iran, Mashhad – literally, “place of martyrdom” – ranks among the holy cities of Shiite Islam. The Imam’s grave became a focus of pilgrimage for tens of thousands annually, making it Iran’s primary Muslim shrine. Only a powerful ruler like Nadir Shah could have introduced “impure” non-Muslims into a religious city like Mashhad, whose Zoroastrian residents had recently been expelled. The Jews settled in the abandoned Zoroastrian neighborhood and even so were barely tolerated.

Mashhad is located on the Silk Road, which connected China and Europe along with offshoots from India and the Persian Gulf. The city’s Jewish merchants benefitted from its position as a trade hub, and in its first hundred years the Jewish community grew to seven hundred families. After Nadir Shah’s death, the fate of the Jews of Mashhad resembled that of Iranian Jewry as a whole (though they were better off financially). They were regarded as impure, required to wear distinctive dress, and in the early 19th century suffered pogroms and blood libels.

Distancing himself from extremist Shia Islam, this Iranian ruler treated all faiths equally. Nadir Shah, late 18th century | Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Iran’s only Shia martyr’s gravesite became one of that faith’s most sacred sites. Tomb of Imam Reza, 1834 | From James B. Fraser’s Historical and Descriptive Account of Persia, 1834, Flickr