Among Jews in the Ottoman Middle East, birth took place in the mother’s home, where close friends and family assisted in an evolving social and spiritual experience. This safe, female space was seminal in women’s lives

Until the early 20th century, birth was far from a medical procedure, particularly in the Middle East, where neonatal wards were nonexistent. Babies were delivered at home by a midwife, aided by the mother’s close female relatives and neighbors. When birth was imminent, mothers sat on low birthing stools provided by the midwife or crouched on rugs or matting.

As the hours or even days of labor dragged on, the women gathered in the mother’s room became a mini-community, offering care and support while timing her contractions and gaging their length. This intimate circle followed the midwife’s instructions, rejoicing when a healthy baby was born.

Outside the “birth chamber” (usually the family’s only habitable space, and too small to contain all those eager to enter), the future father waited tensely, expectantly, with his own friends and family. Whenever anyone stepped out of the room, these men asked for an update on the progress of the birth and the mother’s condition.

Birth was a fraught event, with a high fatality rate for mother or baby – or both. In the 17th century, the Ottoman Empire’s birth statistics were even worse than Europe’s, changing little until modernization began there at the end of the 1800s. Swiss physician Titus Tobler visited Jerusalem in the mid-19th century, lamenting in his Contribution to the Medical Topography of Jerusalem that there were months in which more Jewish mothers died in childbirth than survived. University of Haifa professor Minna Rozen’s research on the Jewish cemeteries of Istanbul has shown that of the forty intact women’s tombstones from the 1700s, eight belong to young mothers who perished in childbirth, while a ninth expired on the day her son was circumcised, eight days after his arrival.

The inherent dangers, the labor pains, and the joy and relief of a successful birth all suffused the atmosphere of the delivery room. The women gathered there shared hopes and fears, knowledge, folk traditions, and skills, forging a lifelong bond.

Belonging

Who were these women? The laboring mother’s own mother would doubtless have been there, at least if this was a first birth; many women considered her essential for subsequent births as well. Her attendance often entailed a journey of days or even weeks; she’d therefore arrive well in advance of the big event to reassure both herself and her daughter. Also present were the father-to-be’s mother, sisters, and sisters-in-law, all of whom usually lived close by.

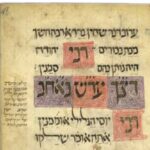

Neighbors often helped as well, taking turns throughout a protracted labor. As the contractions became more frequent and intense, the midwife was summoned. She’d bring a birthing chair, various herbs and minerals to hasten the process and ease the pain, plus talismans and amulets for both mother and newborn’s protection (see “Birth Rite,” pp. 30).