Jerusalem’s water supply has been vulnerable to attack since antiquity, prompting ingenious solutions that have long intrigued archaeologists. What made the city’s water source so unusual – and how was it protected from enemies?

Where To?

Gihon Spring

Water tunnel and fortifications

by the historic City of David

Jerusalem is famously a pilgrim city, drawing tourists every Pesach and Sukkot. The road where irritable bus drivers now honk at the constant congestion beside the Old City entrance regrettably known as Dung Gate was once the main thoroughfare leading from Jerusalem’s main water source, the Gihon Spring, up to the Temple. Each day of Sukkot, water was poured onto the Temple altar in the hope of persuading the Lord to bless us with bountiful rains.

This ceremony began early in the morning, after a night of revelry during which Second Temple sages juggled torches and performed other nifty party tricks. As the assembled wiped sleep from their eyes at the close of another nocturnal Simhat Beit Ha-shoeva (Celebration at the Water-Drawing Site), a procession of priests dressed in white ventured out of the Temple and into the Kidron Valley. One carried a golden water pitcher.

As children cheered and Levites trumpeted, the group stopped at the Gihon Spring, at the bottom of the valley, while the priest filled his vessel with pure spring water. Everyone then trudged back up to the Temple.

The route was the same now taken by musicians accompanying families to the Western Wall for bar mitzvas and by busloads of tourists visiting the Jewish people’s holiest site apart from the Temple Mount. Most have no idea where to find the Gihon and, if they did stumble across it, would probably confuse it with the more famous Siloam Pool – part of a later feat of water engineering (see below). But let’s concentrate on the spring – God’s gift to Jerusalem.

Pumping and Surging

The Gihon as a body of water appears right at the beginning of the Bible, in Genesis 2, where the description of the Garden of Eden includes a river called Gihon encircling the land of Cush. The Jerusalem spring itself is mentioned only in the first book of Kings, when an aged King David sends messengers to anoint his son Solomon as king over Israel and end family squabbles over his soon-to-be-vacant throne. The coronation takes place beside the water:

So Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet have anointed him king at Gihon; and they have gone up from there rejoicing, so the city is in an uproar […]. (I Kings 1:45)

The name of the spring has intrigued commentators for generations, prompting all kinds of interpretations, but the simplest involves the Hebrew root g-h, “surge”: The Gihon is so called because it gurgles up from the ground.

You might think this explanation too literal, as all springs emerge from the earth, but in fact the Gihon was unusual. Every two to three hours, it gushed up for fifteen minutes, as recorded by French Dominican friar and archaeologist Louis-Hugues Vincent in 1909.

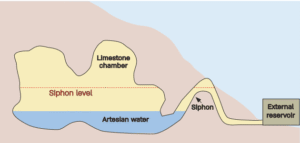

Intermittent springs such as the Gihon are the product of a natural underground basin in which artesian water collects before spurting through a passage in the form of a siphon. Only when both basin and siphon are filled to overflowing can water burst forth from the mouth of the spring. You can actually see this effect in action above ground at Ein Fawar (a.k.a. Ein Mabua), a spring on the Perat Stream, in the Judean Desert.

But as anyone who’s recently gone paddling in the Gihon will tell you, it looks like a perfectly ordinary spring with nothing intermittent about it. That’s because in 1927, a severe earthquake reshaped the basin (though the Gihon was lucky compared to the Ein Rogel spring a few hundred meters further down the Kidron Valley, which has dried up as a result of similar seismic disturbances).

The Spring beyond the Walls

Three immense waterworks have sprung up around the Gihon over the centuries: a subterranean access tunnel, formidable fortifications, and the Siloam water channel and pool.

As all were built right next to each other in a typical archaeological jumble, even the savviest scholars have been scratching their heads for years over the question of which preceded which and what exactly went on here. Adding to the confusion, excavations in the City of David periodically turn up remains that refute all previous theories.

The latest of these finds is an enormous dam dated to the ninth century bce (see “Snapshots,” p. xx), some three millennia ago, and thought to have been constructed to store water from flash floods during a few particularly dry decades. This construction may have been responsible for the Siloam Pool – somewhat later than had been assumed, reassigning it to the Israelite era rather than the Canaanite.

How did the multilayered Gihon-Siloam water system develop?

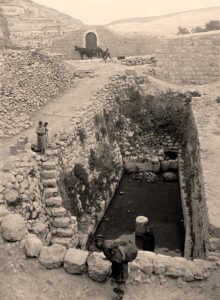

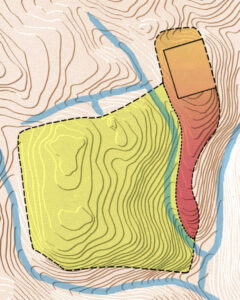

The Gihon discharges an impressive 600,000 cubic meters of H2O a year, making it one of the most plentiful water sources in the Judean Desert. That’s probably why the Jebusites established a city, Jebus, beside the spring some 4,500 years ago. The only problem was the Gihon’s location at the bottom of the Kidron Valley, whereas Jebus was strategically built on the hill above it. Sheer drops on all but the north side made the city more or less impregnable but left the spring outside its walls.

In peacetime, Jebusite women simply popped down to the watering hole, jugs in hand. Under siege, however, not only was water out of reach, but Jebus’ enemies could splash merrily in its shallows while the city’s parched defenders looked on helplessly.

The Jebusites hit on a novel solution. Deep beneath the city wall, they built a tunnel to the spring, ensuring a plentiful water supply safe from prying eyes and enemy arrows. A channel was then dug backward from the mouth of the spring, keeping any excess puddling far from its source.

We can just imagine a frustrated foe encamped beneath the mighty fortifications, intent on besieging the Jebusite city. Well hidden by rocks, trees, and signs boldly pronouncing, “Don’t even think of finding water here,” the Gihon periodically gurgled away. Behind the locked city gates, the Jebusites looked down on their bewildered, thirsty enemies while toasting their own good fortune, clinking goblets of precious water. Eventually the would-be attackers would give up, leaving the Jebusites to enjoy their secret spring in peace.

The Mysterious Shaft

The ancient tunnel was discovered by English explorer and military officer Charles Warren in the 19th century, during excavations carried out by the British Royal Engineers for the Palestine Exploration Fund. Warren spent months digging down dozens of meters, uncovering the steep floor of the Jebusite tunnel, until he reached something unexpected: a duct descending another fourteen meters, known to this day as Warren’s Shaft.

Generations of tour guides have stood by this shaft, Bible in hand, and described how ginger-haired young King David came to capture the city, discovered the spring, and stood peering up through the aperture, wondering how to breach the formidable Jebusite defenses. Wriggling through the narrow but thankfully short tunnel, David realized the key to his conquest was this secret shaft.

Now David said on that day, “Whoever smites the Jebusites and reaches the shaft (tzinor) […].” (II Samuel 5:8)

I Chronicles completes this oblique verse:

Now David said, “Whoever smites the Jebusites first shall be chief and captain.” And Joab son of Zeruiah went up first and became chief. (11:6)

All the pieces of the puzzle seemed to fall into place, with the archaeological record and the biblical text dovetailing for a change – until the late 20th century, when some persnickety researchers poked around a little more and discovered to everyone’s annoyance that Warren’s Shaft doesn’t actually lead anywhere and is in fact a naturally occurring karst chimney as old as time. The tunnel leading from the city to the spring didn’t end at the shaft, but continued a few dozen meters past it, ending at an enormous, hidden, man-made pool into which the spring water was channeled via a short, subterranean extension. Accordingly, the term tzinor, previously understood to mean “water shaft,” had to be reinterpreted as any kind of water system – vertical, sloping, or otherwise.

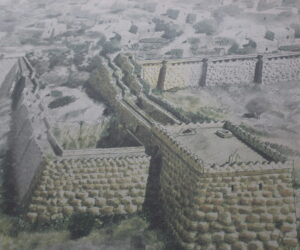

Then matters became even more complicated. Further excavations revealed a Jebusite wall protruding like an ear from the original city wall and interspersed with massive towers that surrounded both pool and spring. Archaeologists wondered: Why dig an underground tunnel to the water when the spring itself was protected by this additional wall?

Possibly, they concluded, there were two stages of development. First the tunnel was dug to provide access to the water beyond the wall; then fortifications secured the spring, obviating the tunnel – and ensuring that no aspiring conqueror or Israelite general Joab could crawl backward from the spring at the tunnel’s mouth and surprise the city.

At this point in our story, the riddle of David’s conquest remains, but two of his city’s three major waterworks – the tunnel and the fortifications – have been connected to the Gihon Spring.