On the eve of World War II, Jews’ domination of Hollywood got political. How Harry Warner’s testimony before the Senate redefined Americanism

Harry Warner wasn’t a nice guy. Years of Hollywood wheeling and dealing had taught him not to waste time on pointless meetings and well-intended suggestions that wouldn’t directly improve his product. What had turned his family’s small photography business into a leading movie studio was his exceptional dedication – and that of his three brothers, Albert, Sam, and Jack – to churning out high-quality, profitable films.

Unlike other studio heads, Warner Bros.’ president avoided the spotlight. Screenwriter Howard Koch recalled that Warner rarely spoke to writers; he conversed only with bank managers – and with his Creator. He worked best behind the scenes. The entertainment industry might have been Warner’s second home, but he preferred his first one, the mansion he’d built his family in Beverly Hills.

One might therefore have expected Harry Warner to resent his surprise summons to Washington in 1941 to testify before a Senate subcommittee on trade relations. Warner Bros. stood accused of producing films intended to undermine U.S. neutrality in the first years of the new world war. It would have been in character for Warner to regard the subpoena as a nuisance to be quickly dispensed with so he could get back to work. Yet he welcomed the opportunity.

Warner was determined to challenge the isolationist policies America had used to barricade itself from events in Europe ever since the late 1930s. His unwillingness to operate in the shadows wasn’t his style; his activism also contravened Hollywood’s generally apolitical nature. His bold campaigning could have been cut from the same cloth as the grit and guts of his own studio’s movie heroes, chasing down Nazi spies in the 1930s, when Warner Bros. was at its height.

Roots in Two Homelands

The 1930s might have been a golden age for the Jews who founded the U.S. motion picture industry, but times were hard for the country as a whole. The 1929 stock market crash had led to massive unemployment, and sandstorms ravaged the southern U.S. Dust Bowl. Yet Hollywood thrived. With silent films suddenly talking and singing, movies became slick and successful worldwide.

While the captains of the American film industry went from penniless immigrants to owners of palatial Los Angeles estates, in Germany the Nazi Party gained strength and stature. For the Jews of Hollywood, the storm clouds gathering over Europe’s Jewish communities – places they’d once called home, and where they still had many relatives – posed a personal threat. Like many other Jews, they grappled with the issue of dual loyalty thrust upon them by the modern era. What came first, their Jewish identity or their American? Should they harness their capital and creative energies on behalf of their brethren? Or, as U.S. citizens, was it time to cut the cord with the old country?

Criticizing the Nazis would cost American Jewish filmmakers the German market. These immigrants’ newfound capitalism made it hard for them to overlook such a clear financial bottom line. And it wasn’t just the waves of hostility rolling in from across the sea that they had to worry about; there were currents of spite just waiting to surge their way within the U.S. itself.

Directors of such major studios as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and Paramount stifled the urge to comment on developments in Europe, fearing being labeled un-American and accused of preferring Jewish interests over domestic ones. This reluctance to denounce the Nazi regime reflected an anxiety characteristic of many successful immigrants. The drive to blend into their new country overrode any lingering attachment to their country of origin; safeguarding their future in the U.S. meant setting aside the past. Considering these widespread tendencies, Warner’s anti-isolationist efforts were remarkable.

Home Movie

Even after founding their studio, Harry and his brothers maintained a strong Jewish identity. Their father, Benjamin Wonsal, had immigrated to the U.S. from Krasnosielc, Poland, in 1888, leaving his family behind. After saving up a little money as a shoemaker, he returned in 1889 to collect his wife, Leah, and their five children. Leah changed her name to Pearl, and the kids too received new names – Hirsch became Harry; Rivka, Anna; Avraham, Albert; Shmuel, Sam; and Raizel, Rose.

Initially the family lived in Baltimore and in London, Canada, eventually relocating to Youngstown, Ohio. The parents were blessed with five more children, and Benjamin and his older sons shod the workers of the growing steel industry.

The Warners got into moviemaking by accident. When Sam apprenticed at a local tourist attraction featuring moving pictures, his father and brothers realized the medium’s potential. Benjamin pawned his watch and horse to buy a film projector, and the local family business soon became a nationwide production company. Taking another risk with the first talkie, The Jazz Singer (1927), catapulted Warner Bros. into the same league as much older studios.

Success, however, didn’t diminish the Warners’ loyalties. Warner Bros. was the first in Hollywood to cut its lossesgive up all revenue from film screenings in Germany by severing all business ties there in 1934. (Jack Warner’s autobiography states that the company closed its German offices in response to the murder of Joe Kaufman, its man in Berlin. Yet there was actually no such person. As in many memoirs written long after the fact, Jack had constructed him out of fragments of information that had come his way.)

In the 1930s, Warner Bros. avoided making explicitly anti-German pictures, lest critics accuse the studio of meddling in matters not its own. Nonetheless, the Warners refused to distribute German films, albeit without declaring an anti-German crusade.

Jewish Propaganda

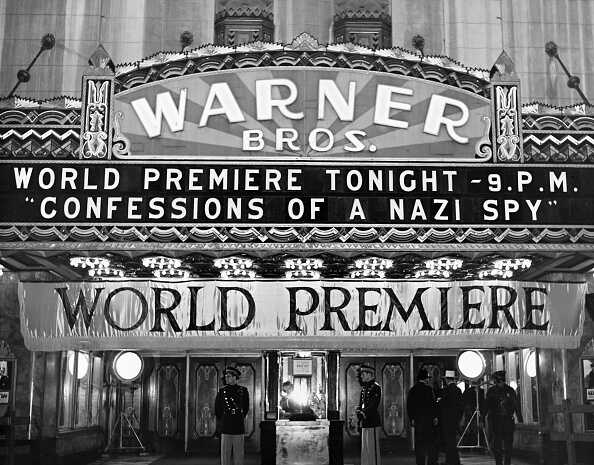

In the late 1930s, Warner Bros. began making movies like The Life of Emile Zola (1937; see box story, p. XX) and Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), which subtly touched on what was happening in Europe. Isolationist senators Barton Weiler and Bennett Champ Clark decried these films’ interventionist agenda. Some in the Senate were openly antisemitic, such as Gerald Nye of North Dakota, who resolved to target the “Yiddish controllers” of the motion picture and theater industry. In a 1941 speech, Nye thundered:

Are you ready to send your boys to bleed and die in Europe, to make the world safe for Barney Balaban and Adolph Zukor and Joseph Schenck? (Scott Eyman, Lion of Hollywood: The life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer [Simon & Schuster, 2012], p. 343)

In Washington, Harry Warner realized that studio heads’ Jewish identity would be a major focus of the subcommittee before which he was to appear. He was the first summoned to testify, and Nye, who attacked Warner Bros., averred that the Senate should familiarize itself with the roots of the leadership there and at other key studios:

In each of these companies there are a number of production directors, many of whom have come from Russia, Hungary, Germany, and the Balkan countries. (Neal Gabler, An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood [Vintage Books, 1989], p. 345)

Nye rattled off a list of movies in which he’d detected an anti-isolationist bent:

Those primarily responsible for the propaganda pictures are born abroad. They came to our land and took citizenship here, entertaining violent animosities toward certain causes abroad. […] I would, in light of what I have since learned, confine myself to four names, each that of one of the Jewish faith, each except only one foreign-born. (ibid. pp. 345–6)

Nye characterized the films in question as propaganda for the war in Europe and warned of their producers’ growing power. He claimed that movies constituted a unique threat because viewers were a captive audience: unlike radio listeners, they couldn’t change the channel upon hearing things they disliked.

Not content simply to criticize specific cinematic content, Nye insisted that the foreign interests of the motion picture industry’s leaders stemmed from their European background.