Beneath the veil of Iran’s current regime, its people have nurtured their pre-Islamic roots with pride. Until June 12, 2025, the Zoroastrian faith, the Sassanid-Persian Empire, and above all Cyrus, “king of kings,” were all part of an identity the Islamic Republic had tried to suppress

Until just a few decades ago, all it took to insult Iranians was to call them Arabs. In recent years, the term Muslim has also become offensive in many Iranian circles, though most Iranians are in fact born into Muslim families. The rivalry between Iranians and Arabs has a lengthy history, beginning with the first Arab conquest of Iran. The crucial Battle of al-Qadisiyyah was fought in 636; Sassanid-Persian king Yazdgerd III was murdered, and his empire finally imploded in 651. Islamification, however, took much longer. Egged on not only by the persuasive power of the sword, but also by the fact that Islam was far simpler to observe than its Zoroastrian precursor, the process still spanned centuries. The Persian Empire’s equation of religion and state helped the transition along. Zoroastrianism had been the official faith since the third century, but by the seventh the regime had lost its luster, paving the way for a Muslim takeover.

In Islam’s first centuries, as it spread north through Mesopotamia and west through North Africa and into Spain, Iranians adopted Arabic as their lingua franca, making it the dominant language of the Middle East. Great works of science and philosophy were either written in Arabic or rendered into it from Greek. But in Iran, Persian remained the lingo of the streets. Physician and philosopher Ibn Sina (Avicenna), mathematician al-Khwarizmi (father of algebra), historian and scientist al-Biruni, and even the first linguist to engage with Arabic, Sibawayh (whose name means “apple-scented” in Persian), all wrote in Arabic but, as Iranians, probably spoke Persian or a local variant at home. Though definitely threatened by Arabic’s domination of science and literature, Persian never died out.

Deal with the Devil

The figure who saved Persian from extinction was poet Abu-al-Qasam Ferdowsi Tusi (d. early 11th century). Author of the Persian epic known as the Shahnameh (written in pure Persian), Ferdowsi singlehandedly saved not only Persian but a distinct Iranian identity. While other nations conquered by Arabia’s Islamic tribes adopted not just Islam but Arabian culture, the Iranians clung to their language and heritage. When asked how a people as ancient as the Egyptians had lost all its pharaonic glory and speech, Egyptian intellectual Mohamed Hassanein Heikal replied: “Because we had no Ferdowsi.”

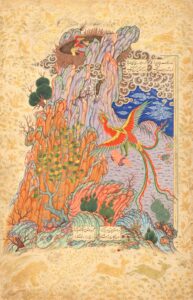

The poet based the Shahnameh on myths and history preserved in Pahlavi manuscripts, written in Middle Persian. This tongue was the language of the Sassanid-Persian Empire, predecessor of the Islamic invaders, who ruled Mesopotamia from the third to seventh centuries. The foundational text of Iranian mythology is the Bundahishn (Primal Creation), and either that or a parallel version served as Ferdowsi’s source.

Yet the author was writing in an Islamic environment, whereas the redemptive end of days envisioned in the Bundahishn is Zoroastrian. He resolved the quandary by concluding the Shahnameh with a different kind of redemption – the seventh-century Arabian conquest. The Zoroastrian cosmology was thus made to accord with the Islamic account of creation, itself drawn from the first chapters of Genesis.

Certain mythological narratives were also rendered somewhat less fantastical in the Shahnameh. For instance, the main villain of Persian mythology, the three-headed dragon, is replaced by a prince who later becomes king and is tricked into a pact with the devil. A snake sprouts from each of the royal’s shoulders, effectively giving him three heads. The pain caused by these vipers can be relieved only by feeding them the brains of two young men daily. The villain’s nationality even changes from one text to the next. In the Bundahishn, the dragon is Babylonian. In the Shahnameh, the prince is Arabian.

According to Persian legend, the Iranians themselves urged the three-headed dragon to replace their rightful ruler, the once beneficent but now haughty Jamshid, who’d made a deal with demons. This depiction of humanity subjugating itself to a deadly monster seems to be veiled criticism of the Islamic conquest, which displaced the Sassanids.

History tends to repeat itself. In 1979, just forty-six years ago, Islam again imposed itself on Iran, replacing the secular, modernist rule of Mohammad Reza Shah. Many Iranians see the Islamic Republic and Iran as two separate entities, distinguishing between the oppressive regime and the oppressed Iranian people. These nationals refuse to call the Islamic Republic “Iran,” reserving that term for some other, hoped-for government. Instead they refer to the current regime as “the Second Arab Conquest.”

Back to the Past

Crowned king in 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi modernized much of Iranian life, such as by introducing family names. Despite his enemies, he’s remembered as a benign monarch. His son Mohammad Reza Shah, an Anglo-Russian appointee who exiled his father in 1941, was less esteemed. Considered a puppet of the West imposing foreign values on Iranian culture, he worked to weaken its religious leaders. One of his tactics was to strengthen national identity over Islamic devotion, turning for inspiration to a figure largely unknown in Iran until a century earlier: Cyrus the Great.

The “king of kings” who transformed Iran into a mighty empire in the sixth century BCE, Cyrus had been expunged from the Iranian consciousness for over two millennia after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire. He was rediscovered by the 19th-century European excavations of Babylonia and other sites in Greater Iran. These revelations sparked a romantic nationalist awakening similar to the one spreading around the globe at the time.

Mohammad Reza Shah saw himself as Cyrus’ heir; he hoped to restore Iran’s status as a key player on the stage of history. Reza Shah even said so at the 2,500th-anniversary celebrations he organized for the great monarch and his Persian Empire at the tombs of the ancient kings near Persepolis. Yet the Iranian people replaced the shah’s authoritarian rule with the seemingly more congenial Islamic Republic of Iran.

Today that revolution is known as the Second Arab Conquest, and its religious coercion and blatant human-rights violations have swung the pendulum of Iranian identity all the way back from Islam to Western-style secularization and national pride. Too late, the shah’s vision of a modern Iran inspired by Cyrus and his descendants has come to pass. After years of neglect, the royal tombs are now a popular pilgrimage site among Iranians.

Nonetheless, there’s no reference to Cyrus in Iranian mythology. Even Sassanid-Persian texts, not to mention the Shahnameh, say nothing about the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Not only is Cyrus missing, but so are his successors, Artaxerxes, Xerxes (sometimes identified with the biblical Ahasuerus), and Darius. Darius III, the last of the Achaemenid dynasty, is cited, but the father attributed to him by Persian myths differs from his actual royal parent.

Until the aforementioned excavations, the sole Persian kings known to ordinary Iranians were from the mythological dynasties, a few Sassanids, and the prophets and monarchs mentioned in the Quran. Only historians immersed in the ancient Greek chronicles or medieval Arabic translations thereof had heard of Cyrus, Darius, and their illustrious Achaemenid descendants.

Iranian Jews were of course familiar with the Persian Empire and its kings, who figure prominently in the final books of the Bible. The Cyrus Declaration, allowing Jewish exiles to return to the land of Israel and rebuild their temples, is described in Ezra and Chronicles – but not outside the Bible. For generations, nothing corroborated the decree’s existence. Then in 1879, excavations in Babylon unearthed the clay Cyrus Cylinder, whose cuneiform inscription enshrined both religious freedom and the right of exiled populations to return home.

Persian cuneiform was also deciphered in the late 19th century, revealing that the ancient inscriptions on the palace walls of Susa, Persepolis, and elsewhere confirmed the Greek historians’ tales of Persian rulers and their political intrigues.