Sea of Pirates

A summer׳s day in 1611. The sun beat down on Morocco׳s pristine beaches, and the port was abustle. Stevedores carried heavy loads of food and supplies down into the cavernous depths of the mighty ships as they rode at anchor, their masts thrusting high into the sky. The breeze rustled their giant sails, its whispers mingling with the rasp of swords being sharpened by sailors on deck. Though no slaves huddled miserably in the hold of these ships, and they harbored no African treasures – no ivory, gold, or spices bound for Europe – theirs was no innocent voyage. These vessels were fast, manned by professional privateers, and set to hunt down Spanish ships laden with the golden bounty of the Americas. Skillfully maneuvered, they were hard to escape.

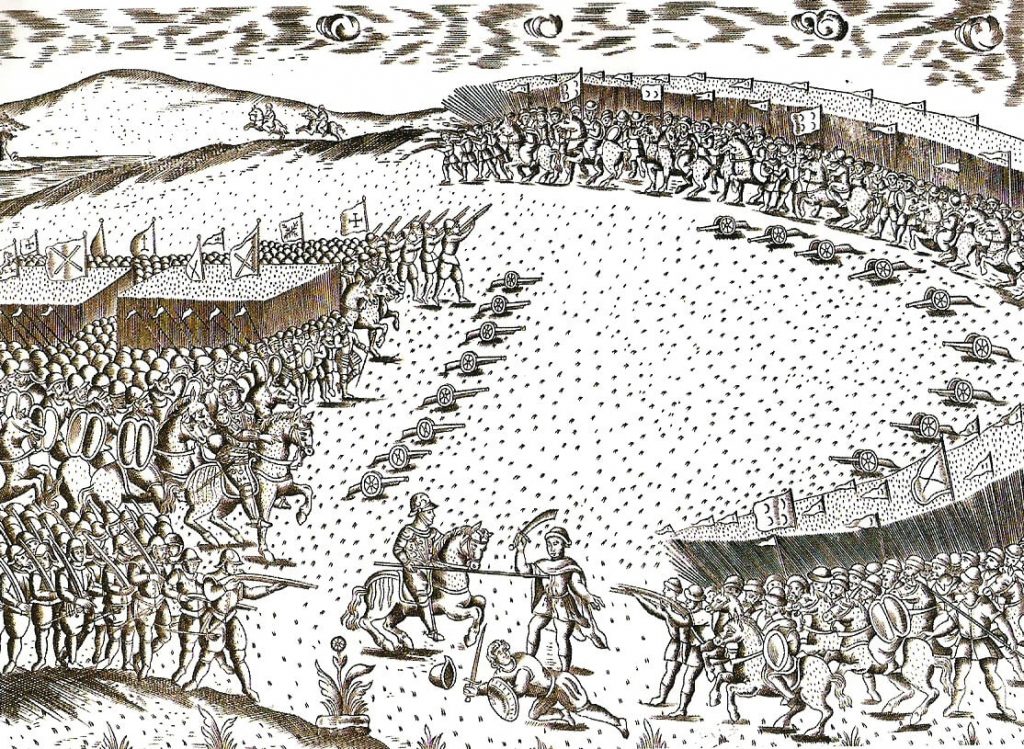

Published in 1629, this etching depicts the relative weakness of the Portuguese army in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir. On display at the Forte da Ponta da Bandeira Museum, Lagos, Portugal

As the Middle Ages drew to a close, such scenes typified ports up and down the North African coast. The Mediterranean was crawling with pirates – whether licensed privateers furthering the interests of their various governments, or ruffians out for themselves. The main difference, as far as any captured crew and passengers were concerned, was that these last were more likely to sell them on the nearest slave market. But this ship was different, for at its helm stood no Captain James Hook or Jack Sparrow but a recent graduate of the rabbinical seminary of the Mellah, the Jewish quarter of Fez. Young Samuel Pallache proudly descended from prominent Spanish exiles, and his command of a pirate ship was just one of the many twists and turns of his exceptional life.

Key Traders

Don Samuel Pallache was born around 1550 in Fez, where his parents had ended up after the Spanish expulsion, and where the customs of thousands like them were swiftly altering Moroccan Jewish tradition. Pallache׳s father, Isaac, headed a rabbinical academy, and Samuel at first seemed destined to follow in his footsteps, receiving ordination at a tender age. His next move, however, was to start a trading business with his brother Joseph, quickly building himself a substantial reputation. His sons and nephews all played key roles in Moroccan commerce, some as customs and excise officers in the ports, others as international merchants. A few eventually served as diplomatic emissaries in Europe.

In 1578, after three monarchs – Don Sebastian of Portugal and two Moroccan sultans – had lost their lives in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir (also known as the Battle of Three Kings), Morocco emerged victorious. Its importance increased, and European powers vied for its favor. The Pallache brothers׳ business experience and fluency in both Arabic and Spanish made them useful agents for Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur (The Golden One; 1578–1603), starting with a currency exchange deal in 1591. Once they׳d won his confidence, their missions grew much more influential, but after al-Mansur׳s death, their fortunes took an unexpected turn. As succession struggles threatened to tear Morocco apart over the next decade, the wealthier members of the Jewish community looked back to Spain, of all places, for security. As Jews were still barred from the Iberian Peninsula, the grandchildren of those who׳d sacrificed everything for Judaism now requested Church protection, converting for purely pragmatic reasons and returning to Spain. (Some claim that even Samuel and Joseph Pallache tried this route but were rebuffed.) Inquisition records show that these converts were targeted for persecution, under the probably correct suspicion that their conversions weren׳t sincere.

Although he neither emigrated nor converted, Samuel remained extremely close to the Spanish nobility until his death. He may have been a double agent, receiving vast sums from the Spanish crown in exchange for insider information from the royal court of Morocco. Certainly he understood the enormous financial potential of a Moroccan treaty with Spain. But whatever his clandestine activities, his interventions on behalf of his people – and his stubborn and anything but clandestine struggle against Spain – reveal his true sympathies.

In 1607, the two brothers arrived in Madrid posing as traders, but they were soon forced to flee (which they did with the help of friends in high places). We don׳t know why they were driven out, but if they were attempting to bring conversos back to Judaism – as some think – they would undoubtedly have brought the Inquisition down on themselves like a ton of bricks.

Moroccan Jewish Ambassador

A historic peace treaty between Morocco and Holland in 1610 bears all the stamps of Pallache׳s involvement. He׳d been appointed to a diplomatic position in Holland by Muley Zaydan, al-Mansur׳s successor, in 1608, and this treaty was a landmark in Christian-Muslim relations. Samuel signed the pact, ratifying it on the sultan׳s behalf, and reports from the time emphasize Dutch prince Maurice of Nassau׳s admiration for the Jew׳s intelligence and abilities.

Maurice of Nassau was Samuel Pallache׳s patron and friend, working behind the scenes for his release from British jail. Prince Maurice receiving a diplomatic delegation from Russia in 1614, presumably in the same chamber in which he frequently hosted Pallache. Charles Rochussen, oil on canvas, 1874

After Holland and Morocco concluded their peace treaty, Muley Zaydan awarded Pallache exclusive rights to trade with Holland – an extremely lucrative prospect. Pallache promptly convinced Maurice of Nassau to help him build a fleet of eight ships and man them with an attack force of two thousand, who would storm Spanish galleons returning from America and make off with their precious cargo. Just a year earlier, France had negotiated a Spanish-Dutch armistice agreement (known in retrospect as the ״Twelve Years׳ Truce,״ because that׳s how long it lasted). Pallache׳s scheme clearly violated this treaty, but Maurice detested Spain (as did Samuel, for obvious reasons), and he was promised a generous portion of the spoils.

Proudly flying Moroccan colors, the fleet of Dutch caravels set out in the summer of 1611. Leading this piratic adventure was Rabbi Samuel Pallache. A Jewish cook sailed on every voyage, so no food cooked by non-Jews or otherwise forbidden by Jewish law need ever pass the pirate chief׳s lips. The expeditions continued until Pallache׳s death in 1616.

Diplomatic Disturbance

Samuel left Holland on yet another privateering mission against Spain in the winter of 1614, but something went wrong. It might have been a storm, or a plague that struck his crew, but his ship was forced to lay anchor in Plymouth, off the English coast. His unexpected visit is described in the correspondence of John Chamberlain, a well-connected English man of letters whose papers provide a wealth of information on 17th-century England. A letter addressed to Dudley Carleton, the British ambassador in Venice, and dated November 4, 1614, records:

Here is a Jew Pirate arrested that brought three prizes of Spaniards into Plymouth. He was sent by the King of Morocco and was sailing in a Dutch ship . . . he shall likely pass out of here well enough, for he has league and license under the King׳s hand for his free egress and regress, which was not believed until he made proof of it. (reprinted in Jewish Quarterly 14 [1902])

As soon as the Spanish ambassador in London heard of Pallache׳s arrival, the Jew was arrested for the seizure of the three Spanish ships. Samuel produced a letter he׳d obtained for just such an eventuality, signed by the king of England on October 25, 1614, and allowing him free passage throughout His Majesty׳s territory, but to no avail: England׳s good terms with Spain carried more weight than any foreign corsair׳s claims. Samuel was brought to trial in London.

The resulting storm in a diplomatic teacup proves just how much heft Pallache wielded. Noel de Carron, the Dutch ambassador in London, put himself at Samuel׳s beck and call, writing numerous letters and even arranging an audience with King James I to testify in Pallache׳s favor. Samuel seems to have made quite an impression in court as well; the clerk seated him at his side, and he was permitted to keep his head covered even though court protocol demanded that all in attendance remove their hats. Acquitted, Pallache was freed even before the trial was officially over.

Leaving England in May 1615, presumably with some relief, Samuel headed back to the Netherlands, pausing en route to take revenge on Spain. His sturdy, three-masted vessel attacked a Spanish flagship, confiscating much of its cargo. Pallache had apparently planned to lay this booty at the feet of the Turkish sultan, hoping to establish diplomatic ties between his patron, Muley Zaydan, and the Golden Porte, and strengthen the alliance against Spain. But this time fate was against him. A fatal illness forced him to sail straight to Holland, where he received a hero׳s welcome.

Samuel Pallache died in the Hague on 16 Shevat, February 4, 1616. His funeral was as elaborate as any aristocrat׳s; Prince Maurice and other Dutch nobles joined thousands of Jews accompanying Pallache׳s coffin to the Jewish cemetery of Ouderkerk, on the banks of the Amstel River. A lion and crown are engraved on his tombstone, which hails him as wise and ״blessed with the favor of man and God.״

Few Jews have been as adept as Samuel Pallache at seizing the opportunities offered by a world in flux, both to increase their own wealth and advantage and to benefit their fellow Jews. Scholar, diplomat, adventurer, and pirate, this colorful character opened his compatriots׳ eyes to the myriad possibilities awaiting one who dares to break the mold and win – or steal away – the jackpot.