Amsterdam, Holland’s greatest city, epitomizes liberalism and freedom. The famous coffee shops of the De Wallen neighborhood, the red-light district, the free-flowing alcohol at the many breweries, and the general “anything goes” atmosphere attract millions of tourists in their twenties – and even younger – to this canal-riven city annually.

Tolerance has characterized Amsterdam ever since its golden age in the 16th and 17th centuries. Though its fervent Calvinists condemned all manner of luxury and frivolity, the city gained a reputation for open-mindedness verging on lawlessness. That ideology was rooted not in the puritan Calvinist population but rather in the town’s growing community of Portuguese conversos.

Dutch Independence

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, Amsterdam was the prosperous capital of a global empire. For close to a hundred years, it was also the world’s financial center.

Originating as a federation of seven provinces in 1581, the Dutch republic had no official religion or absolute ruler. Its only unifying factor was the urge to shake off Spain’s despotic rule, adopting a relatively liberal constitution that later inspired the U.S. Constitution.

The golden age of Dutch art was launched by the rise of Holland’s middle class. Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild

With no inherited aristocracy to speak of, Dutch society rested on its middle classes and wealthy merchants, residents of its fast-developing port cities. The Dutch East India Company, founded in 1602, became the world’s first public company by issuing bonds and stock options to the Dutch people. The firm was also the first global conglomerate, with its peak market value matching that of today’s Apple, Amazon, and Google combined. As for culture, Dutch masters such as Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Peter de Hogh were the brightest stars in an artistic pantheon whose workshops depicted the everyday, bourgeois life of the upper middle class.

Much of the Netherlands’ success stemmed from its liberalism and religious tolerance. After the revolt of the United Provinces in 1568, Spain invaded the southern Low Countries – modern-day Belgium and Luxembourg – conquering the vital western European port of Antwerp and launching hostilities that continued on and off for over half a century. Protestant England helped block the Spaniards’ advance northward. Non-Catholics under Spanish rule were subjected to heavy taxation and religious persecution, resulting in a mass exodus of wealthy Calvinist merchants, who abandoned the southern ports for those of the freer north. Many settled in Amsterdam, then a sleepy seaside town. They were followed by more waves of religious refugees: French Huguenots, English Puritans, and the well-endowed offspring of New Christians – conversos – from Portugal.

Simultaneously, the Netherlands became a colonial power, conquering much of the East Indies (now Indonesia), Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Formosa (Taiwan), and Malacca (Malaysia). Amsterdam thus came to offer extensive economic opportunities for both investors and entrepreneurs.

Culture Shock

The first New Christians arrived in Amsterdam in the late 1500s and were allowed to practice freely as Jews. By 1610, they numbered five hundred, and a decade later their ranks had doubled. Throughout the 17th century, Amsterdam became a center for descendants of Spanish and Portuguese conversos. Their community was rich not only materially but in study halls and Talmudic academies. Its homegrown rabbis served Sephardic congregations all over western Europe and in the New World.

Among the conversos converging on Amsterdam was young Gabriel da Costa Fiuza, who’d followed a tortuous path from Portugal. Born around 1583 in Porto, Gabriel was the son of a well-to-do Christian merchant and tax collector and his New Christian wife. Da Costa held a clerical post in Porto and studied canonical law at the University of Coimbra. Directly exposed to the biblical text, he began doubting Christian dogma, eventually rejecting it entirely and resolving to become a Jew.

After the death of Gabriel’s father in 1608, the Da Costas encountered financial and legal difficulties and left Portugal. As the departure of any New Christian required a host of permits and paperwork, the family exited secretly, reaching Amsterdam in April 1615. The Da Costas identified as Jews on arrival, and Gabriel took the Hebrew name Uriel. Together with his brother Abraham and their mother, Uriel continued up the coast to Hamburg, where they joined the fast-growing community of ex-conversos. Two younger brothers remained in Amsterdam.

For many Portuguese conversos, returning to Judaism was no simple matter, since they had neither knowledge nor family traditions to lean on. All they knew was largely superficial and based on limited familiarity with the Bible. Furthermore, their understanding of Judaism was shaped by the Christian way of thinking with which they’d grown up. Thus, they related to Judaism as a creed rather than a way of life. As crypto-Jews, they’d long separated what they considered the private personal phenomenon of their inner religious belief, from their outward behavior, assuming that what you thought was more important than what you did. Thus, even now as Jews, they prioritized dogma over deed.

“The Marranos” by Moses Maimon, oil on canvas, 1893. Original hanging at the Hebrew Home for the Aged, Riverdale, New York, USA

Encountering rabbinic Judaism, with its emphasis on halakhic minutiae, the returning conversos were not always enthusiastic. As outsiders, they had trouble grasping the logic of Jewish law and finding its basis in the Bible. Some accepted every ritual detail nonetheless. Others chose selective conformity, toeing the line just enough to remain within the community while maintaining their own lifestyle. Still others groped toward some kind of compromise between Jewish and Christian outlooks, reinterpreting Jewish law along the way.

The concurrent emergence of rationalism –and the advent of skepticism – also shaped this process. Such thinking was as threatening for Calvinist Dutch society as it was for the community of returning crypto-Jews. In 1615, Dutch theologian and lawyer Hugo Grotius demanded that every Jew requesting residence in Holland swear belief in the Creator, Providence, and the immortality of the soul. Likewise, testimony delivered before the Inquisition tribunal in Lisbon in 1617 claimed that a certain converso from Amsterdam who’d reembraced Judaism was an “Epicurean or atheist who believes in no religion at all” (Yosef Kaplan, An Alternative Path to Modernity: The Sephardi Diaspora in Western Europe, p. ??).)Uriel da Costa was no exception to this struggle. Normative Judaism wasn’t what he’d expected, as he wrote in his Latin autobiography, Exemplar Humanae Vitae (Example of a Human Life):

I had not been [in Amsterdam] many days before I observed that the customs and ordinances of the modern Jews were very different from those commanded by Moses. Now if the Law was to be strictly observed, according to the letter, as it expressly declares, it must be very unjustifiable in the Jewish doctors [i.e., rabbis] to add to it inventions of a quite contrary nature. (Uriel da Costa, Examination of Pharisaic Traditions, appendix 3, Uriel da Costa’s own account of his life, trans. John Whiston [London, 1740; reprint, Brill, 1993], p. 557)

In Pursuit of Truth

Unlike his fellow ex-conversos, Da Costa didn’t hide his opinions. He wrote to the parnasim (trustees) of the Jewish community in Venice, enumerating his reservations about rabbinic Judaism. His harshest criticism was directed against the Oral Law, which he saw as no more than a human fabrication.

If so, having shown that there is no law or interpretation apart from the Written Law, which is from God, it emerges that what is known as the Oral Law in the above-mentioned literature is of human origin and can be contradicted […]. And if indeed it is evident that these are of human composition, it would be great apostasy to treat them as divine law and say we’re obligated to observe all the rules in the Talmud just as [we’re bound to observe] the law of Moses. (quoted by Rabbi Leon of Modena, Magen Ve-tzina, p. 3a [Hebrew]

Da Costa aimed his choicest barbs at the manufacture of tefillin and mezuzot, the art of circumcision and the accompanying rite of metzitza (oral suction), the extra day of festivals observed outside the land of Israel, and the annulment of vows.

Venetian communal leaders passed Da Costa’s comments on to Rabbi Leon of Modena, who denounced them as heresy, warning his Hamburg colleagues that the author would be excommunicated unless he recanted. Modena carried out his threat in the summer of 1618 in Venice’s Ashkenazic synagogue, writing a treatise titled Magen Ve-tzina (Shield and Shelter) to deflect Da Costa’s criticisms.

Beyond the Pale

By challenging the soul’s immortality, Da Costa offended both Christians and Jews. Suspected of atheism as well as heresy, he was arrested in Amsterdam in May 1624, jailed, and released only after paying a steep fine – in addition to his brothers’ posting a surety of twelve hundred gulden. All copies of his tract were forfeit, and burned in Amsterdam. Indeed, the text was thought to have been lost, until a copy was discovered in the Copenhagen Royal Library in the early 1990s.

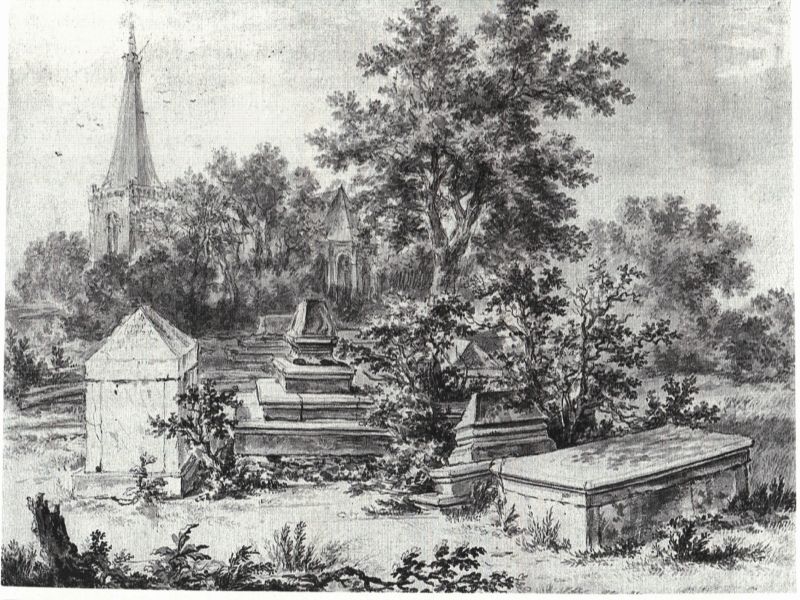

Though the excommunication pronounced in Venice and Hamburg was evidently never enforced in Amsterdam, da Costa left the city, settling with his wife and mother in Utrecht, where he lived in isolation for four years. Shunned by the rest of his family, he returned to Amsterdam only in October 1628, when his mother died and was buried in the Portuguese Jewish cemetery in Ouderkerk, just outside the city. Only the intervention of Da Costa’s brothers secured a Jewish burial; many claimed that, as a resident in the heretic’s home, this woman should be denied a resting place among them.

Meanwhile, Uriel began inquiring about rejoining the Portuguese Jewish community. Although there’s no proof that he officially recanted, Da Costa definitely lived in Amsterdam from 1629 onward, where he held an account at the city’s Wisselbank and was a member of a Jewish charitable society. His personal views, however, remained unchanged. As he put it in his Exemplar Humanae Vitae: “How much better will it be to return [outwardly] to their communion and to conform to their ways, [lit., like an ape among the apes] in compliance with the proverb that directs us ‘at Rome, to do as they do at Rome’?” (Da Costa, pp. 558–9).

Da Costa didn’t last long within the communal framework. In 1632, the Amsterdam Jewish authorities adopted the ban issued in Venice, and he sank once more beneath the burden of his “heresy.” What prompted this new attack on his reputation? Da Costa’s autobiography accuses his family of alleging that he disregarded Jewish dietary laws. Similarly, claims this work, two non-Jews testified that he’d advised them against converting to Judaism. In any case, the author never renounced his controversial opinions; in fact, they only strengthened over the years.

Public Humiliation

The saga came to its tragic conclusion in 1639. Da Costa’s wife had died in 1630, and his lonely isolation persuaded him to reattempt reconciliation with the Jewish community. This time, however, as the excommunication edict had been confirmed in Amsterdam, no oral retraction of his “errors” would suffice. He had to undergo an official ceremony, which he described in appalling detail.

The United Talmud Torah Congregation’s new synagogue was jam-packed with “men and women out of curiosity to be spectators” (Da Costa, p. 560). At the podium, Da Costa confessed all his sins, recanted, and asked forgiveness, vowing never again to diverge from the rulings of the community’s rabbis. He was then told to strip to the waist and blindfold himself, and his hands were tied to one of the platform’s support beams. Though over fifty, Da Costa was subjected to thirty-nine lashes – “it being a precept of their law that the number of stripes shall not exceed forty. For these very scrupulous and religious gentlemen take due care not to offend by doing too much. During the time of my whipping they sang a psalm” (ibid., p. 560).

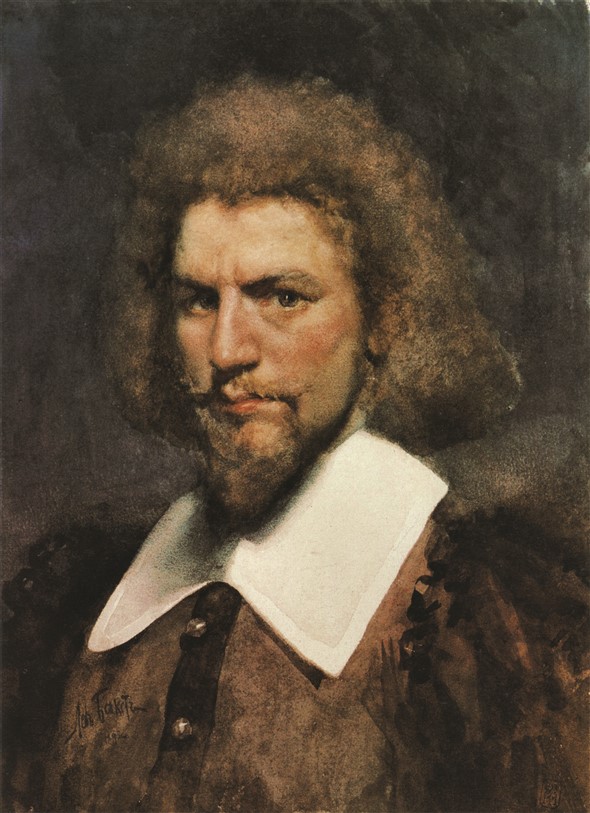

Maurycy Gottlieb’s representation of a barefoot de Costa beating his breast while recanting his “heresy” before the entire congregation

Finally, clothed once more, Da Costa was made to lie over the synagogue threshold and the entire congregation trampled him as it walked out.

This indignity was more than he could bear:

Now let anyone who has heard my story judge how decent a spectacle it was to see an old man, a person of no mean rank, and who was moreover exceedingly modest, stripped before a numerous congregation of men, women and children and scourged by order of his judges and those such as rather deserved the name of abject slaves. (ibid.)

Da Costa never recovered from his ordeal. He fell into a deep depression, and in April 1640, he shot himself. One account claims he was aiming for his nephew, who’d denounced him as a heretic to the leaders of the community. On the writing table behind him, Uriel had left his Exemplar Humanae Vitae, the only extant source of information regarding his excommunication in Amsterdam and the shameful proceedings by which it was dissolved. The community records mention nothing of his case.

Exemplar was published in the 17th century by Dutch theologian Philip von Limborch, in an appendix to his disputation with Jewish thinker Isaac Orobio de Castro. The fact that a document detailing such an inhumane Jewish ceremony was printed as part of an anti-Semitic debate made it immediately suspect. Researchers assumed the description was exaggerated to cast Jews in an unfavorable light.

Recently, however, historian Yosef Kaplan highlighted an unusual entry in the United Talmud Torah Congregation’s Book of Verdicts, depicting the removal of a ban of excommunication from one Abraham Mendes, whose offense was adultery. Held the same year as Da Costa’s public humiliation, this procedure was quite similar:

Moreover, he shall mount the teva and read the declaration which the Gentlemen of the Mahamad have imposed on him and he will be given public malqut (39 stripes) before the congregation. Then he will prostrate himself at the foot of the stairs [at the exit to the synagogue] so that all the congregation may step over him. (cited in Yosef Kaplan, “The Social Functions of the ‘Herem’ in the Portuguese Jewish Community of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth Century,” in J. Michman, ed., Dutch Jewish History, vol. 1 [Jerusalem: The Institute for Research on Dutch Jewry, 1984], pp. 141–3)

Far from Fame

Unlike his younger and much more famous contemporary Benito Spinoza (1632–1677), whose Bible criticism might well owe something to Da Costa’s influence, Uriel left no lasting impact. Examination of Pharisaic Traditions vanished almost totally except for references by Rabbi Leon of Modena, Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel, and other writers who cited Da Costa only to refute him. A few Christian authors quoted him too, hoping to link Sephardic Jewry to the Sadducees.

Yet the Enlightenment recast Uriel da Costa as a tragic hero, a free spirit and free thinker whose death was a protest against religious tyranny. Both Voltaire (1694-1778) and German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) saw him as a harbinger of philosophical deism, and he became the subject of novels and plays. A German drama, Uriel by Karl Gutzkow (1811–1178), was translated into Hebrew and Yiddish and staged in Jaffa in April 1905 with considerable success. Israel Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto, published in 1897, was inspired by Da Costa’s life story as well; Abraham Frumkin produced a Yiddish translation in 1907. As for other art forms, Samuel Hirszenberg painted an imaginary meeting between Da Costa and a youthful Spinoza in 1901, and an Uriel Acosta suite was composed by Karol Rathaus in 1936.

Da Costa’s personal tragedy reflects the complexity of Jewish society in the early modern period. Shaken by the radical shifts in belief and attitude that would alter the Western world forever, Amsterdam’s converso community was at once fiercely conservative yet home to diverse opinions and practices. Uriel da Costa far from typified the Sephardic enclaves of Amsterdam, Hamburg, Livorno, London, and Bordeaux. If anything, he was an outlier on the spectrum they represented, compelled to speak out yet desperate to belong. Spinoza’s individualism – a product of the decades following Uriel’s death – was beyond him. Having wrenched himself away from the Portuguese Christian society in which he’d matured, da Costa couldn’t survive without alternative social support. So he had to accept the framework of the Amsterdam Jewish community, and the severity of its rejection was his downfall.

Further reading

Herman P. Salomon and Isaac S. D. Sassoon, eds., Examination of Pharisaic Traditions (Brill, 1993); Yosef Kaplan, An Alternative Path to Modernity: The Sephardi Diaspora in Western Europe (Brill, 2000).

The Perils of Ostracism

Though excommunication was a powerful social tool, Amsterdam’s Portuguese Jews discovered its limitations

With no other means of enforcement at its disposal, the Jewish community had but one means of policing its members both socially and religiously: the herem. The right to impose this ban was one of the privileges granted the Jews by the Dutch authorities. Hugo Grotius specifically stated as much in a document regulating the status of Jews in Holland:

The masters of the Jews or those who are appointed to that end among them, will have the right to excommunicate and ostracise Jews whose way of life or opinions are evil. (Yosef Kaplan, An Alternative Path to Modernity: The Sephardi Diaspora in Western Europe , p. 133)

Yet Grotius limited these abilities, stating that the municipal authorities of Amsterdam would serve as a court of appeal:

Nonetheless, anyone who wishes to complain that he was excommunicated even though he was innocent, should submit his complaint to the local authorities, who will investigate the matter and decide according to the laws of the Old Testament. (ibid. p.133-4)

Grotius’ detailed outline of Jewish rights and privileges in Holland was not officially accepted, but in practice, things in Amsterdam ran along the lines he’d suggested.

The Amsterdam Jewish community made frequent use of the ban during the 17th century. Between 1622 and 1683, no fewer than forty of its members were excommunicated. These included the Del Sotto family, which had attempted to take over the community leadership, and Isaac Penhamacor and his son, who’d refused to pay communal dues in protest against the way the congregation’s finances were run. Even Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel was placed in herem for a day for disregarding a community warden’s instructions.

Spinoza, Excommunicated (1907) was one of Samuel Hirszenberg’s last paintings, while his imagined portrait of da Costa and a young Spinoza was among his first

In the end, the ease with which bans were imposed in Amsterdam proved their undoing. On 26 Tammuz 5437 (July 26, 1677), Dr. Joseph Abravanel Barbosa of the Portuguese Jewish community was ostracized for buying chickens from an Ashkenazic butcher. Incensed, Barbosa turned to the municipal authorities, who duly ordered the ban revoked. The Portuguese leadership retaliated by expelling the doctor from the congregation. Once again, the consequences were unexpected: a number of respected Jews immediately cancelled their membership too.

Realizing they’d set a dangerous precedent, and facing a heavy loss of synagogue dues, community leaders pointed out that all such defectors wouldn’t be buried in the Portuguese cemetery, nor could their family members recite Kaddish in the Portuguese synagogue. In addition, ex-members wouldn’t be included in a prayer quorum. Some of those who’d asked to leave promptly changed their minds, including Barbosa, but others continued the struggle to disassociate from the congregation.

By the second half of the 17th century, the ban was used for political and financial ends rather than as a religious weapon. Yet this application only encouraged disgruntled parties to turn their back on the community, weakening it dramatically.

In January 1683, the Amsterdam authorities forbade the Portuguese congregation to ostracize its members without municipal permission. Though this requirement was later cancelled, it shows how abuse of religious authority can backfire.