In Yiddish, the Good Die Young

In one of the opening scenes of Jewish American playwright Tony Kushner’s celebrated work Angels in America, which debuted in the U.S. in the early 1990s, a young Jew named Louis Ironson is walking out of a New York cemetery when he falls into conversation with the elderly rabbi who has just eulogized his grandmother. Louis confesses that he had not visited his grandmother in years, and had in fact assumed she was already dead. The rabbi replies: “Sharfer voy di tson fun a shlang is an umdankver kind.” When Louis admits in perplexity that he does not speak Yiddish, the rabbi deigns to translate: “‘How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child! Source: Shakespeare, King Lear.’”

The humor of the scene lies not only in the incongruity of the Shakespearean phrase on the aged rabbi’s tongue and the young New Yorker’s failure to identify it, but also in the genuinely natural flow of the quotation from Lear in Yiddish. What sounds like a Yiddish folk saying – a pithy epithet aimed by elderly parents at their thankless children – turns out to be a well-crafted line from one of the greatest playwrights’ finest tragedies.

Two of Shakespeare’s plays were particularly beloved by the Yiddish theater: King Lear and The Merchant of Venice. The latter, featuring the only Jewish protagonist in the bard’s repertoire, was an obvious choice. But why did American and European Jewish audiences in the early 20th century identify with the vicissitudes of an elderly medieval English king?

Let us recall Lear’s trials. Having banished his youngest daughter, Cordelia, for refusing to flatter his vanity, he abdicates the throne and moves in with each of his two older daughters in turn, who now rule the kingdom in his place. But the girls soon show their true colors, refusing to provide for their father in the manner to which he has become accustomed, and ultimately throwing him out in bald-faced denial of all they owe him. Sound familiar? And then, of course, Lear loses his mind and dies, together with his beloved Cordelia. In Shakespeare, as in Yiddish humor, the good always die young.

The Emigrant King

King Lear was evidently first produced for the Yiddish stage by Jacob Gordin (1853–1909), one of the most important playwrights of the American Yiddish theater, at the outset of his career. After emigrating from the Ukraine in 1891, Gordin began writing for the Yiddish stage to earn his keep. He was horrified by the lack of professionalism he found there: the highly unlikely plots, with their impossible jumble of comedy, tragedy, and melodrama; the bawdy jokes, dance routines, and popular music-hall numbers thrown in at random; actors who grabbed center stage and basked in the crowd’s affection; and raucous, rowdy audiences that ate and drank throughout performances, accompanied by children of unsuitable ages. Vociferous audience response to all the goings-on onstage was a matter of course, resulting in a very lively theater experience with an engaged and devoted following. Breaching all norms of the cultured Western stage, this form of entertainment was affectionately if dismissively known by the Yiddish derogative shund, “trash.”

Gordin resolved to replace this shund with serious theater, aiming to educate as well as entertain. His highly structured, realistic plays initially mystified theatergoers and alienated actors, who insisted on modifying his scripts to accommodate their usual interactions with the crowd. Gordin found a willing partner in Jacob Adler (1855–1926), the great Yiddish stage star. Their first production, Siberia, met with mixed reviews to say the least – including catcalls and requests for refunds – but Gordin’s works swiftly became smash hits, transforming the Yiddish theater.

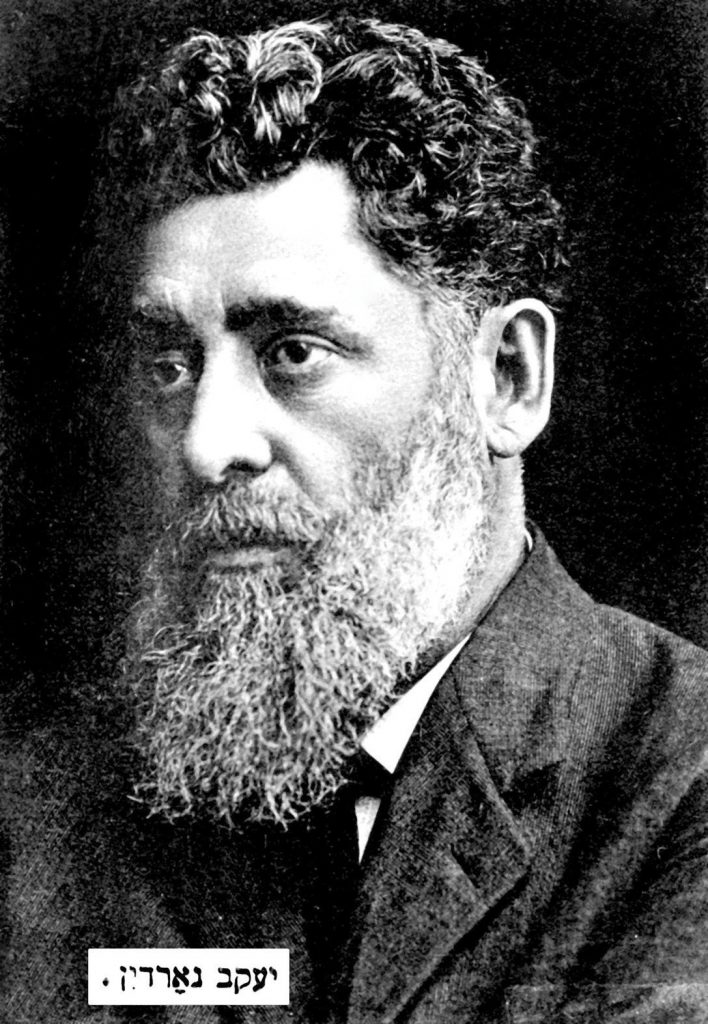

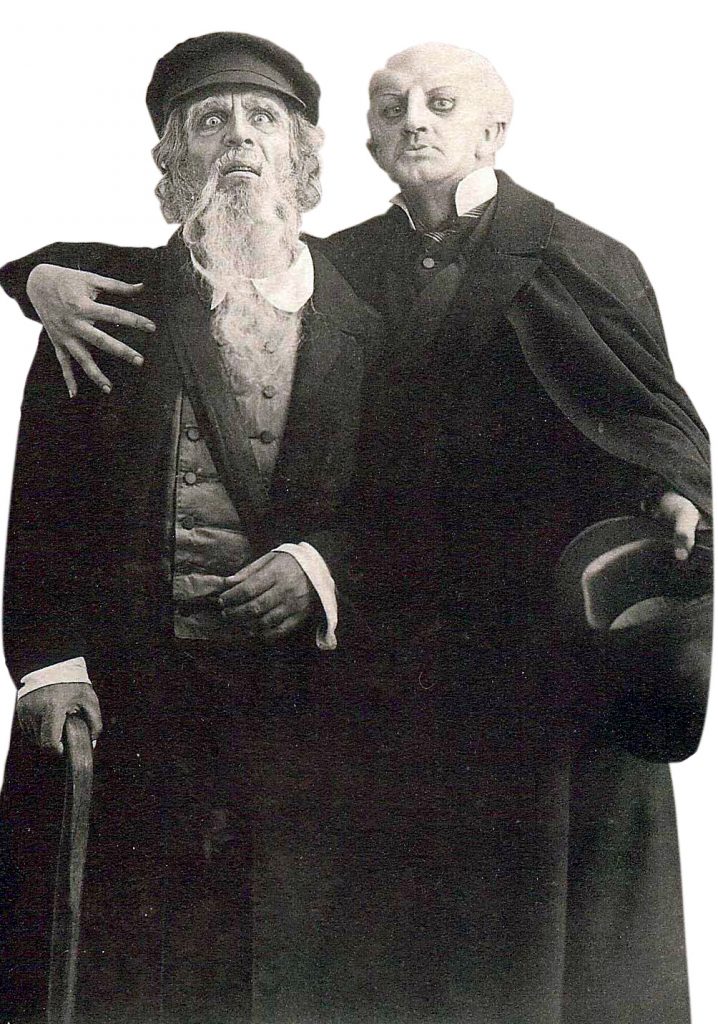

Odessa’s loss, England and America’s gain. Jacob Adler (far right) with other actors from the Yiddish theater, New York, 1888

The Jewish King Lear (1892) was apparently the turning point. This play was no mere Yiddish translation of the Shakespearean tragedy, but a reworking of the original in a Jewish context. The tragic hero is Dovid Moysheles, an affluent Jewish businessman from Vilna who decides to apportion his wealth among his three daughters and move to Palestine. The two older girls are in favor, but his beloved youngest, Taybele, disapproves, prompting Moysheles to throw her out of his home. In his absence, the older daughters and their fiancés take over the family business, leaving him penniless. By the time Moysheles returns, illness is blinding him, and he is forced to live off charity. Five years later, we find him begging on the street with his loyal servant, Shammai. Taybele has meanwhile become a doctor, and on her wedding day Moysheles and Shammai come calling. In the happy ending, even Moysheles’ blindness finds a cure.

The covert links with King Lear are inescapable, but Gordin left nothing unsaid. Taybele’s fiancé, her tutor Yaffe, tells Moysheles about Shakespeare’s famous drama. “You’re the Jewish King Lear,” Yaffe informs him. “May God protect you from King Lear’s fate.” These lines were intended to enlighten the audience, as well as its protagonist, regarding the deeper meaning of the play.

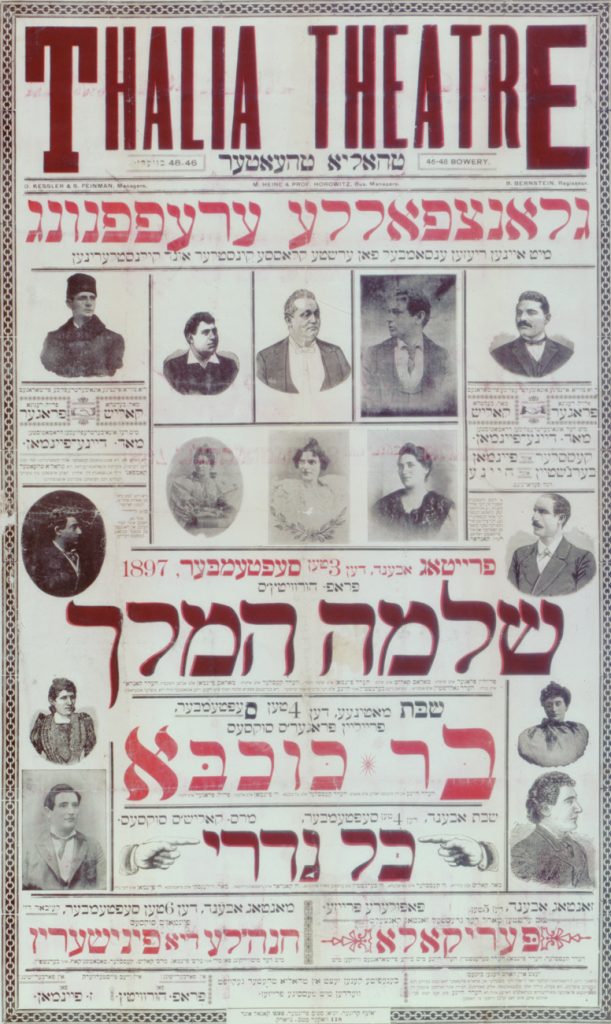

Advertising highlights of the upcoming season of New York’s Yiddish theater, 1897

Placard for a New York performance of Gordin’s Jewish King Lear, starring Jacob Adler, October 1898

Gordin strove to broaden his audiences’ horizons, hoping to turn them into enlightened, sophisticated theatergoers. He met with relative success: The Jewish King Lear was followed in 1903 by a performance of Shakespeare’s original – in Yiddish – with Hamlet, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, and other classics in close pursuit over the next decade.

Jacob Adler as Shylock in a Yiddish production of The Merchant of Venice, 1903

According to researcher Iska Alter, Gordin’s unique contribution to King Lear was his dramatic treatment of the family. Faced with unprecedented hardship, migration, and social and cultural upheaval, Jews turned to the family, even more than the community, for stability. The Jewish King Lear’s kingdom is his home. He rules his business and family but nothing more. While the drama of this Lear allowed Jewish audiences to reflect on the changing parent-child relationship, its happy ending reaffirmed the vital place of family in their lives. It proffered hope that, despite tumultuous circumstances, children might not abandon their parents after all – in stark contrast with the ghastly disintegration of family ties in the original play.

Joel Berkowitz further notes that each of Dovid Moysheles’ daughters is engaged to a representative of a different Jewish cultural movement. There is Abraham, the sharp-tongued Lithuanian scholar; the eponymous Moshe Hasid; and Yaffe, a modern intellectual derisively called “the German.” The storyline thus reflects the choices facing the Jew in the modern era. It is no coincidence that Gordin depicts the Orthodox as thankless hypocrites, whereas only the Enlightenment Jew, seemingly disconnected from his heritage, upholds traditional family values. The subliminal message is that the Jew who knows Shakespeare, as did Gordin himself, does not just promote progress and universalism; in his loyalty to and support of the older generation, he is also the true guardian of tradition – a reassuring message for an audience whose children were steadily assimilating into modern American culture.

Prototype of the Jewish Mother

Success, it seems, naturally breeds sequels. Several years after The Jewish King Lear, Gordin penned an equivalent for his leading actress, Keni Liptzin (1856–1918). Mirele Efros, the Jewish Queen Lear premiered in 1898.

Wealthy, tough-minded Mirele Efros saves her late husband’s business from bankruptcy and rules her two sons with an iron hand. The older boy, Yosele, marries Shaindel, whose vulgar parents claim an impressive rabbinical lineage. Shaindel and her parents conspire with Donye, Mirele’s other son, to win control of her fortune. Infuriated by their constant accusations, Mirele abandons the business, leaving it in their incompetent hands. Predictably, the family finances take a downturn, and tensions escalate. When Shaindel beats Machle, Mirele’s loyal maid, the matriarch can take no more. She leaves home and moves in with Shalmon, her business manager. Many years go by. Mirele regains her lost wealth while the original business collapses. As Yosele and Shaindel’s son approaches bar mitzva, they invite Mirele to the festivities and beg her forgiveness. The grandson, Shloime, manages to reach beyond Mirele’s initial refusal to attend, persuading her to allow the family to reunite.

Once again, Gordin has reconfigured Shakespearean tragedy as family melodrama with an upbeat ending. But explicit allusions to Shakespeare are no longer necessary. The alterations of the original plot – all the strong characters are women, while the men merely react to their decisions – reflect real changes in the intervening years: in the role of women in the family and in the economic matrix of modern Jewish society.

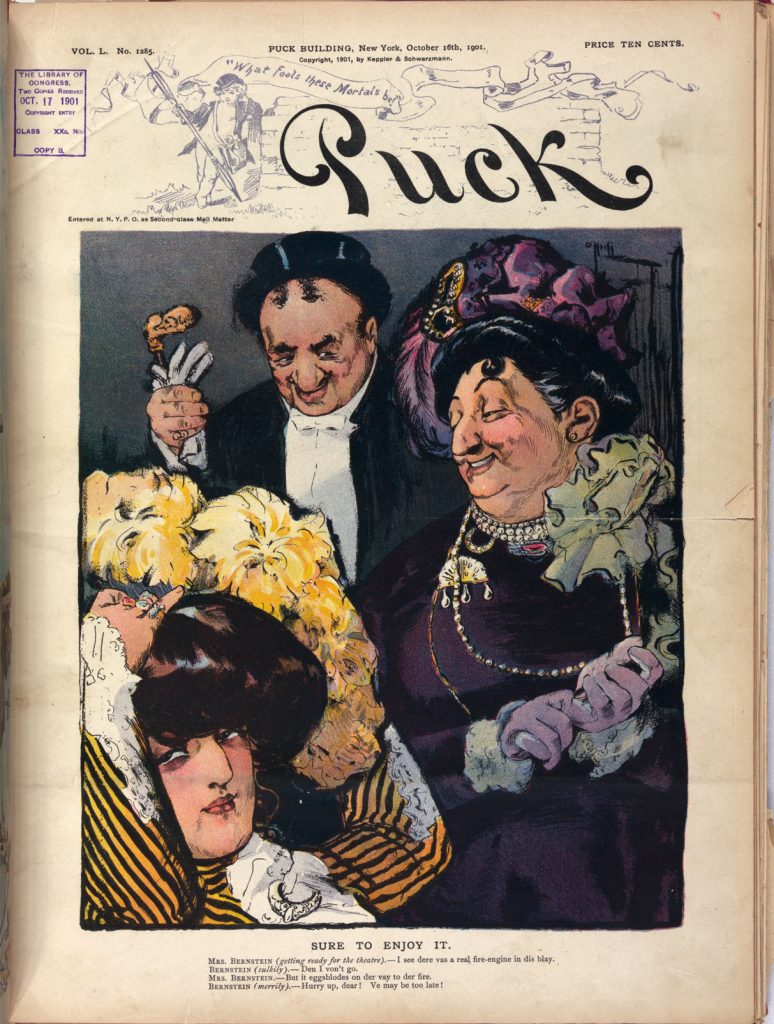

Seeking entertainment, Yiddish-speaking audiences were unprepared for a heavy dose of Western culture. Rose Cecil O’Neill’s “Sure to Enjoy It,” a caricature of a Jewish family on its way to the theater, appeared in the satirical magazine Puck, published in New York, 1901

In Mirele Efros, Gordin created one of the most prominent female roles on the Yiddish stage, portrayed by such luminaries as Esther-Rachel Kaminska and her daughter Ida as well as the great actresses of the early Hebrew theater: Hannah Rovina, Lea Kenig, Miriam Zohar, Orna Porat, and Yona Elian.

Gordin also launched a stereotype destined to figure prominently on stage and screen: the Jewish mother. While it seems odd that the Jewish-mother persona may owe her origins partly to Shakespearean tragedy, King Lear’s encounter with the Jewish matriarch produced a character who copes with her children’s ingratitude with dignity and pathos, as befitting a melodrama rooted in tragedy. And it laid the foundations for a whole genre of Jewish humor. Lear’s piteous insanity may be a long way from Mirele’s proud refusal to put up with her daughter-in-law’s effrontery, but from there it is only a small step to such well-known utterances as “I’ll rest in the grave,” and “Don’t worry, I’ll sit in the dark.” Perhaps Kushner’s rabbi’s graveside comment was not so incongruous after all.

Laughing as You Cry

In 1935, across the ocean and in a totally different political climate, King Lear was restaged in Yiddish with a very different purpose. The actors belonged to the Melukhisher Yiddisher Teater, the State Jewish Theater, better known by its Russian acronym, GOSET.

GOSET had been established in 1918 as a state theater committed to the socialist revolution and approved by the Communist Party. Its director was Aleksandr Granovsky, whose training as a producer seems to have outweighed the fact that he spoke no Yiddish. Granovsky had worked with some of the most innovative artistic directors of his time. His method relied heavily on improvisation, and he refused to work with experienced actors. The idea was to avoid saddling his work with previous artistic conceptions, particularly the realistic tradition of the Stanislavsky school. Granovsky built an impressive acting curriculum, including training in voice, rhythm, diction, and calisthenics, as well as theater history, Jewish history, and Yiddish language and folklore. Under the guidance of his right-hand man, actor Solomon Mikhoels (1890–1948), his actors reconstructed the speech and body language they remembered from the shtetl and used them to create, of all things, avant-garde theater.

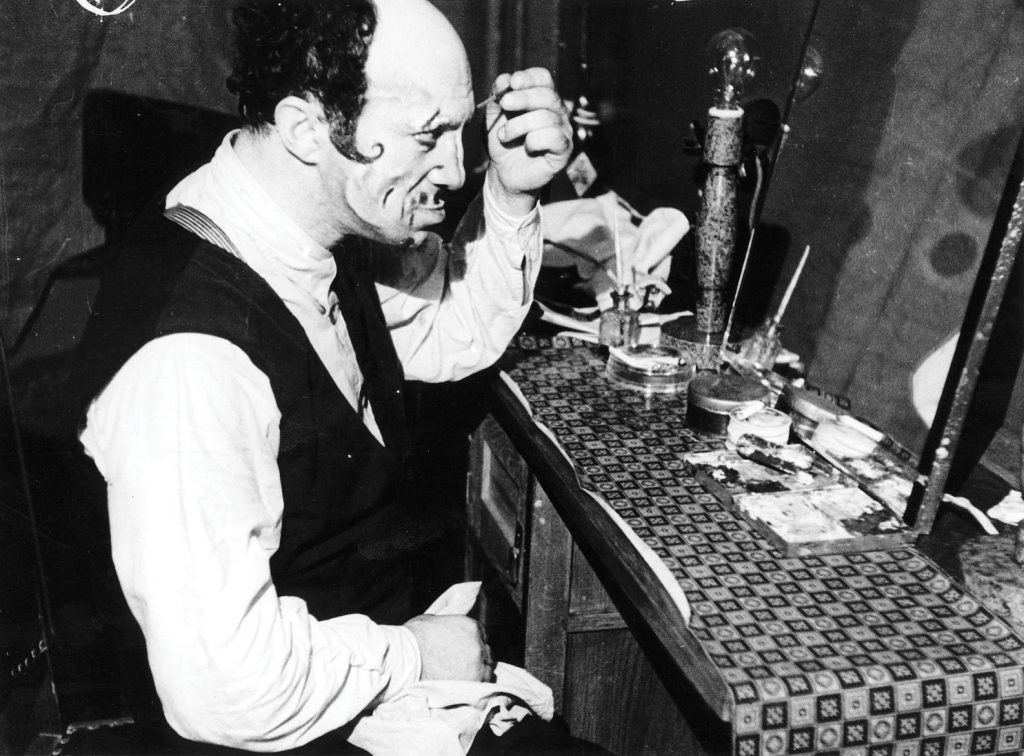

The most striking aspect of Solomon Mikhoels was his grotesque appearance, which first brought him to Granovsky’s attention. Mikhoels’ “monkey face” was perfect for the developing theater of the absurd, and he soon became the company’s principal actor. His uncanny ability to mix the grotesque with the poetic made him a superb Lear, which would become one of his greatest roles.

Although King Lear is a tragedy, it shares many aspects of grotesque drama: the jester/fool and the king who behaves like one; figures who lose their sanity or only pretend to; blind characters groping their way across the stage; and staged or failed suicides. And like all Shakespearean tragedies, King Lear has its comic moments, tending from the sublime to the ridiculous.

These tragicomic elements made Lear a natural vehicle for GOSET. From the company’s earliest days, Mikhoels claimed that only tragicomedy could express the pathos and suffering of Jewish life. “The comedians of the Jewish theater travel over the ruins of Jewish Ukraine,” he remarked (Benjamin Harshav, The Moscow Yiddish Theater: Art on Stage in the Time of Revolution, p. 26).

Tragicomedy soon became a hallmark of GOSET. Far from diminishing the tragedy, the comic touches allowed it to avoid the lofty idealization that would have blunted the agony of Jewish existence. Celebrating the ugly as only the theater of the grotesque can, GOSET tackled the most delicate, painful subjects. It was about as far from Gordin’s melodramatic Lear as communism was from capitalism.

Dangerous Political Satire

The GOSET production of King Lear was of course rife with political innuendo. Although Granovsky, Mikhoels, and actor Benjamin Zuskin all received the Soviet People’s Artist citation in 1927, tensions mounted rapidly thereafter as GOSET’s artistic direction clashed with Communist Party ideology. From the 1930s onward, Soviet authorities grew less tolerant of avant-garde theater, even if it expressed the radical spirit of the Communist revolution. Socialist Realism, with its inherent conservatism, was swiftly becoming the only acceptable artistic representation of revolutionary values. Thus, GOSET cut back on obviously Jewish subjects and sought out more neutral Yiddish material.

Shakespeare was a convenient choice. Some fifteen of the bard’s works had been approved by the Central Repertoire Committee of the Communist Party, and Shakespearean productions proliferated in the pre-war Soviet Union as a result. Directors often used Shakespeare’s texts to express veiled political criticism. GOSET’s version of King Lear was a case in point, as shown by historian Jeffrey Veidlinger. Directed by Sergei Radlov, the production portrayed Lear as a self-centered monarch demanding constant loving remonstrations from those around him.

The focus of Mikhoels’ performance was not Goneril’s and Regan’s betrayal of their father, which would have portrayed Lear as a victim, but rather his foolish rejection of Cordelia’s sincere affection. Responsibility was thus placed squarely on the shoulders of the paranoid leader who cannot distinguish between calculating sycophants and true friends. Audiences suffering under Stalin would have needed no further explanations.

At the beginning of the play, Mikhoels appeared dressed as a disheveled old man and shuffled hesitantly toward the throne. As one critic complained, you could barely tell he was supposed to be a king. Finding the throne already occupied by Zuskin – the fool – Mikhoels first seemed confused, then yanked him by the ears from his royal seat. Finally, with a feeble chuckle, he settled himself down in the fool’s place. As a metaphor for the state of the regime, the staging was brazen and powerful, perhaps even foolhardy.

GOSET’s King Lear captivated crowds and critics alike, and Mikhoels’ performance established him among Russia’s greatest actors. He became well-known in the USSR and headed the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (see The Night of the Murdered Poets).

After World War II, Mikhoels’ U.S. contacts and Zionist leanings made him a prime subject of Soviet suspicion. In January 1948, he was murdered at Stalin’s instructions while on an official trip to Minsk, ostensibly to evaluate a play for the prestigious Stalin Prize. The Communist Party shut down GOSET a year later. Zuskin was murdered August 12, 1952, together with twelve other poets, artists, and intellectuals on the “Night of the Murdered Poets.” Just as Mikhoels had always known, their tragedy of the grotesque had unmasked the regime of terror in all its gruesome evil.