New in Town

On the second day of the week, on 14 Nisan of the year 5675 from creation, according to the calendar we use here in the holy city of Bisan (may it be established and rebuilt), which lies by brooks and is watered by their streams […].

So begins a Jewish marriage contract (ketubba) written and signed in Beth She’an (then better known by its Arabic name, Bisan) in 1915. The groom, Farj son of Binyamin Mizrahi, and his bride, Miriam, daughter of Yosef Mizrahi, had apparently both been living in this small town in the Lower Galilee. Bisan’s obscure Jewish community was mostly Kurdish, having relocated from Kurdistan and Tiberias a few years earlier.

In the rapidly diversifying Jewish population of Ottoman Palestine, where did the Jews of Bisan fit? Could their community be considered part of the Zionist settlement efforts of the late 19th century? If so – and even if not – why have these Jews been all but forgotten?

A Jewish community in the Holy Land without initial ideological pretensions. British Mandatory Bisan

From the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th, the Jewish population of the Holy Land grew dramatically – and changed radically. Prior to this transformation, the local Jews were mainly Arabic-speaking Sephardim. They were now joined by Ashkenazic immigrants from Poland and Russia, the vast majority of whom were pious Jews. Next came small groups from elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa, including Yemenites, Moroccans, and Tunisians. Zionism’s first wave of immigration began only in the 1880s, but these thousands of mainly Eastern European Jews quickly altered the Jewish demographics of Ottoman Palestine.

Far more numerous and diverse than the existing Jewish population, the new arrivals spread out in the second half of the 19th century, settling in the traditional centers of Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, and Hebron as well as where Jews had long been absent. These new locations were very different from the holy cities and included the ports of Haifa and Jaffa as well as something new: agricultural colonies. Communes and cooperative settlements, not necessarily agricultural, followed in the early 1900s.

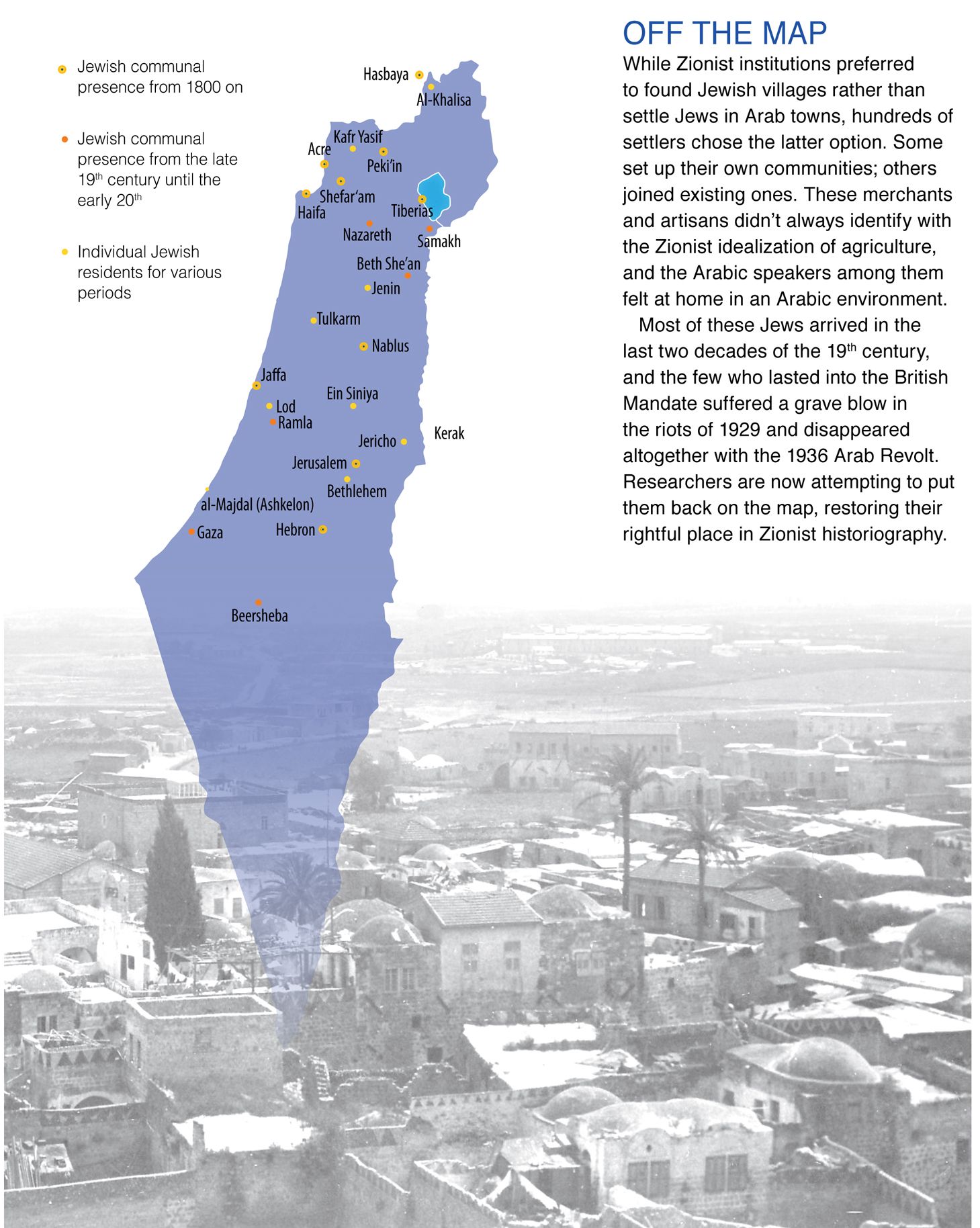

While Zionist settlement has generated extensive research and public interest, few are aware of the Jews who made their homes within the urban Muslim sector. Taken together, these individuals, families, and even small communities constituted a not insignificant proportion of Ottoman Palestine’s Jewish population – about a thousand in all. The overleaf map shows that said pockets of Jews existed all over the country; most were established around the turn of the century. The remains of an ancient Jewish community in Nablus (Shekhem) and a larger one in Akko also continued functioning among the Muslims. There were a number of families spread over a few Arab villages in the Galilee as well, most notably in Peki’in and Shefar’am, whose Jewish communities dated several centuries back.

Very few of these clusters numbered more than a hundred. Some formed gradually as individuals and families moved in; in other cases, small groups relocated together. Some emulated the Ashkenazic communities in the holy cities, relying on charity. Others labored to support themselves or drew on savings. Some put down roots and remained for years, while others ebbed and flowed. Though most of these Jews had come to Palestine for ideological reasons, their choice of location was largely economic. Nevertheless, philanthropic or idealistic associations sometimes lent a hand – at least at first – in creating and maintaining a Jewish communal infrastructure.

Białystok and Gaza

Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer’s For the Sake of Zion (Lema’an Ziyon) organization, founded in Berlin in 1888, backed the Jewish communities of Ramle, Jenin, Lydda, and Jericho. As widely publicized in the Hebrew journals of the period, the association encouraged self-supporting Jewish settlement in the Holy Land (though some funding went to scholarly communities as well). Any form of livelihood – trade, craftsmanship, or agriculture – qualified for aid. In addition, Hildesheimer’s group encouraged Jews to set up shop in Arab cities with no permanent Jewish presence.

Several Arab towns and villages contained small pre-state Jewish minorities. Jews in Peki’in circa 1930

Another such organization was Revival of Israel (Tehiyat Yisrael), cofounded by Nissim Bekhar and supporting mainly Ramle. Both Moses Montefiore and Baron Edmond de Rothschild assisted Jews in Arab towns, and after World War I, the Zionist establishment in Mandate Palestine followed suit.

Why settle Jews in Arab cities? First, this effort would allow Jews uninterested in agriculture to provide for themselves in the Holy Land by other means. Second, it would renew ancient Jewish communities in locations of historic or religious significance, such as Bethlehem, Jericho, and Beersheba. Finally, there was an urgent need to extend Jewish settlement beyond the holy cities and the Zionist population blocks of the coastal plain and the Galilee, to which immigrants naturally headed.

Leaders of the Lovers of Zion (Hovevei Ziyon) movement shared this last approach. As Russian tea manufacturer Kalonymus Ze’ev Wissotzky famously wrote in Ha-Melits (The Advocate) daily after visiting Ottoman Palestine in 1885:

In my opinion, Hovevei Zion should do nothing but open the eyes of our brethren and our people, the workers and laborers among us, and tell them: Dear brothers, there are still many towns in the Holy Land where no Jews live – such as Nablus, Nazareth, Lydda, Bethlehem, Gaza, Ashkelon, Tyre, Sidon, Acre, and more – and as people eat there and walk about clothed and shoed, there must be a need for all kinds of artisans and laborers […].Whoever has enough imagination to see that Gaza could be like Ponevezh […] will be able to earn his meager ration of daily bread in Ramle just as he did in Białystok, Vilna, or Minsk. (“Support for the Scribes,” Ha-Melits, 19 Adar II, 5646/March 26, 1886, p. 2)

He hoped Bisan’s Jews would build cultural bridges with the local Arabs, contributing to Jewish-Arab dialogue in Palestine. Colonel Frederick Kisch, the Zionist Commission’s head of the Jerusalem area, 1923–31, and a British officer in both world wars

Jews settling in Arab towns encountered financial, organizational, and security challenges, but even those who supported them offered little help. To make matters worse, many of these pioneers – at least until the British Mandate – didn’t particularly identify with political Zionism and its aspirations for a Jewish state.

As the 20th century progressed, the trickle of Jews into Arab towns dwindled, ending altogether amid the disease and famine brought by World War I, the Arab riots against the Jewish population in 1929, and the Arab Revolt of 1936.

Following the Train

The story of Jewish Beth She’an is fairly representative of similar communities at the time, though few were as well established and organized. Recognizing the Beth She’an Valley’s agricultural potential, strategic value, and proximity to a well-used crossing point bridging the Jordan River, the Ottoman authorities invested heavily in the area in the late 19th century. Bisan became a regional capital, and steps were taken to spur its economic growth. Jews naturally followed. In 1905, Bisan’s importance increased with the opening of its train station, a branch of the Hijaz Railway (see “Trainspotting,” Segula 17).

The first Jewish residents of modern-day Beth She’an had no organizational backing. They arrived of their own volition, working as laborers, artisans, and small-scale traders in the town and surrounding Bedouin villages. There were several wealthy Jewish realtors and merchants as well, whose dealings took them as far as Damascus, at the end of the train line. Most Jews in Bisan hailed from the Erbil region of Kurdistan, but there were also Ashkenazim and North Africans.

Bisan’s new prosperity spawned a thriving community of Jewish merchants and artisans. Market scene

By the turn of the century, there were only a few dozen Jews, not enough to create a communal infrastructure. During World War I, however, a Jewish council was formed, headed by Zaki Elhadif (later mayor of Tiberias, where he was killed by an Arab assassin in 1938). By 1929, the community numbered two hundred and boasted a synagogue and (thanks to the Mizrahi movement) a kosher butcher. In 1924, the Hadassah health organization had founded a clinic. Shortly afterward, a Jewish school opened its doors, run until 1934 by teachers sent by the World Zionist Organization’s Education Department.

Mini-Museum

The clinic was particularly welcome, serving Jew and non-Jew alike. As Do’ar Ha-yom (Daily Mail) later reported:

This small Jewish colony has revitalized the city, and the resulting traffic is clearly evident. Life here is very quiet, and the Jews and their neighbors enjoy good relations. Much of this is due to the Hadassah organization, which opened a clinic a few years ago, where all residents can receive medical attention regardless of all [religious and ethnic] distinctions. Cultural life revolves around the doctor’s and teachers’ residence. This center serves all comers, not only residents of the town. The doctor has a collection of fauna – a live eagle, all manner of live snakes – and artifacts. More interestingly, he has a well-organized coin collection, with coinage from various periods, including the Maccabean. No visitor to Beth She’an misses the opportunity to visit the physician’s miniature museum. (“The Jewish Community of Beth She’an,” Do’ar Ha-yom, 2 Sivan 5687/June 2, 1927, p. 2)

The school also made a big difference. Its teachers shaped the town, each uniquely contributing to this faraway, barely recognized community. Avraham Salomon, grandson of Petah Tikva founder Yoel Moshe Salomon, taught in Bisan for three years. On the first day of Av in 1929, less than three weeks before the Arab riots changed Jewish life there forever, he wrote to the Zionist Executive’s Education Department:

Despite the difficulties involved in accepting new pupils – both young and old, who know not a word of Hebrew – I haven’t shirked the challenge and continue to accept them. My attitude has been that it’s better to compromise our classes’ homogeneity than neglect these Jewish children who seek a Hebrew education, abandoning them to the Arabic-language government school or to the street. (Central Zionist Archives, s/2/22/1)

The doctor and teachers gradually strengthened the community’s Zionist affiliation, initiating contact with such Zionist bodies as the JNF, the National Council, and the Jewish Agency.

Beth She’an’s distinctive black basalt buildings and pavement derive from the volcanic rock of the Galilee. Washing the streets, 1920

In addition to their own institutions, the Jews of Beth She’an had a representative on the town council. For a few years, the position was filled by the Jewish community’s unofficial “mukhtar,” David Israel Mizrahi.

Had all remained calm, the Jewish presence in Bisan would presumably have continued growing. But this was not to be.

Exile

Generally speaking, Jews and Arabs coexisted peacefully in Beth She’an from the turn of the century, though there was friction here and there. At the time, these conflicts were attributed to normal tensions between neighbors. As the Jews established themselves, however, and clashes on Jewish and Arab national issues multiplied, the situation deteriorated. In August 1929 (Av 5689), everything changed irrevocably.

It was a quiet Sabbath morning, August 28 (18 Av), when the rioting begun in Jerusalem the day before (after Muslim prayers on the Temple Mount) spread to Bisan. Most of the Jewish community was in synagogue when hundreds of Arabs attacked. The building was defaced, and dozens of Jews were injured, some severely. Houses and shops were robbed as the Jews fled under British police protection. Their exile lasted almost a year, partly because the Arab population announced a strict boycott of Jewish businesses, instantly destroying the livelihood of many Jews.

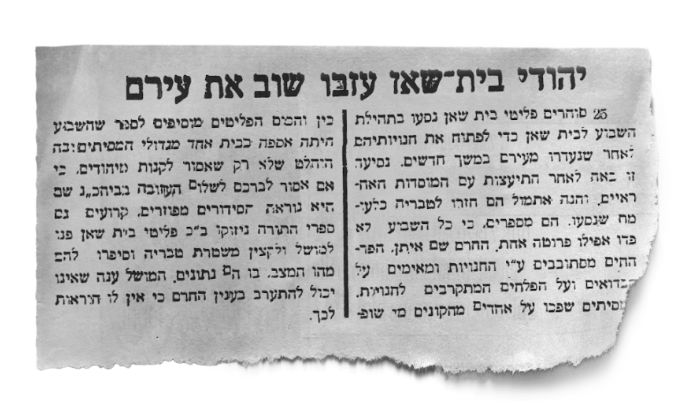

Press clippings following the bad news from Bisan. On September 23, 1929, Do’ar Ha-yom continued its coverage of the riots, and two months later, the paper reported the Jews’ evacuation

Press clippings following the bad news from Bisan. On September 23, 1929, Do’ar Ha-yom continued its coverage of the riots, and two months later, the paper reported the Jews’ evacuation After much persuasion by Zionist institutions, part of the Jewish community returned home in 1930, but nothing was the same. Those Jews brave enough to remain were constantly accosted by their neighbors, and the boycott continued. Though the Jewish school reopened, and the Hebrew Community Committee of Beth She’an was founded, Jews kept leaving. By 1936, there were just ten Jewish families and a doctor.

Once the Arab Revolt broke out that April, the last Jews were evacuated, and their property stolen. Left with nothing, the refugees found shelter in Tiberias, where they struggled to regain financial independence. A year later, a few tried to coordinate their return to Bisan, approaching the director of the National Council, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, for help.

The pre-state Jewish mayor of Tiberias spearheaded attempts to resettle Jews in Arab Bisan. Zaki Elhadif

The pre-state Jewish mayor of Tiberias spearheaded attempts to resettle Jews in Arab Bisan. Zaki Elhadif But they failed to convince anyone to invest the necessary personnel and resources to ensure their safety. A subsequent initiative by Yosef Weitz of the JNF also fizzled. Apart from the locals’ hostility, the Zionist organizations were discouraged by the proposed partition plans of Mandate Palestine. With Beth She’an an entirely Arab city, possibly destined to be assigned to the Arabs, why send Jews back there? Many other needs were much more pressing.

At the beginning of 1937, physician Yosef Lehrs reappeared in Bisan in response to requests from the municipality. His safety had been guaranteed by local notables, but on February 26, men came knocking at his door in the middle of the night. They shot him point-blank, killing him where he stood – and ending forty years of Jewish life in Beth She’an.

Visiting Bisan, he couldn’t tell the Jews from the Arabs. Joshua Gordon, the Zionist Organization’s liaison to the British military government

On May 12, 1948, after repeated clashes between the Hagana and the Arab Legion, which was using Bisan as a base from which to attack nearby kibbutzim, the town surrendered to the Jewish militia. The population fled to Nazareth or Jordan.

In 1949, a year after the State of Israel was established, Beth She’an (as it was now officially known) was repopulated by Jews from Iraq, Iran, North Africa, and Romania.

Out of Sight, Out of Mind

So why were the Jews of pre-state Beth She’an so swiftly forgotten? Perhaps because their stay was by and large short-lived – like other Jewish attempts to settle in Arab towns – and made no long-standing impact. Even at their height, however, these communities were all but ignored. The Zionist establishment focused mainly on agricultural settlements, having no faith in the viability of Jewish islands surrounded by hostile Muslims.

Beth She’an resident Yaish Shoshana with Deputy Mayor David Levi, spring 1967. Levi became almost synonymous with Beth Shean, serving in Israel’s

parliament for thirty-seven years. His various ministerial posts included absorption, housing, and foreign affairs

Out of sight and out of mind as far as the Tel Aviv political center was concerned, the Jews of Bisan were also mostly religious, Oriental, and Arabic speakers, far removed from the secular Ashkenazic socialists running the show. And as small-time traders, they figured little in the broad sweep of central Zionist planning.

A few months after the final evacuation in 1936, there were accusations that the community had been shamefully neglected throughout its short history. David Israel Mizrahi and Yihye Dahan, the refugees’ representatives, wrote bitterly to the National Council on July 13, 1937:

You regard us as Arab peasants from Beth She’an; we’re worth no more than an Arab peasant in your eyes. But you’re totally wrong. There was a Zionist Jewish community in Beth She’an, and if you had nothing to do with it, that’s not our fault. (State Archive, F-59/1908)

***

Further reading

Reuven Gafni, A Jewish Community in an Arab Town: Beth She’an, 1890–1936 (Magnes Press, 2018) [Hebrew].

*

Ze'ev Kainan | סגולה

Ze'ev Kainan | סגולה