Meet the Parsis

On November 26, 2008, a Pakistan-based terrorist group unleashed three days of fatal strikes on Mumbai, India. People around the world looked on in horror as the attacks, primarily in the city’s high-class southern end, targeted economic, tourist, transportation, and medical centers. Beyond the obvious tragedy for the residents of Mumbai, the majority of whom are Hindu, for two small religious groups with communities spread across the globe, the Mumbai assault struck personally. The Parsis – a group of Zoroastrians who immigrated to India from Iran in the Middle Ages due to religious persecution – witnessed the attacks up close. For centuries, the Parsi community has been concentrated in South Mumbai, and some of the structures targeted were proud symbols of its success on the subcontinent. Among Jews, the focus of the attacks was the Chabad House – a spiritual and physical watering hole for Israeli and other Jewish tourists located in an old Zoroastrian landmark known as Nariman House. Even now, the attacks remain a painful memory for Jews. In the Israeli media, discussions of the Mumbai tragedy are often heartbreakingly juxtaposed with a photo of the smiling, radiant young religious couple who ran the Chabad House, who were murdered there along with four others.

A few months before the attacks, I was living in Manhattan’s Little India. One rainy Friday afternoon, I sat down with anthropologist Leila Vevaina of the New School, who was writing a thesis on notions of communal space in Mumbai’s Parsi neighborhood, where she was born. In the course of her research, Leila had learned of the Jewish concept of the eruv and was fascinated by the way eruvin have encouraged Orthodox Jews to congregate in neighborhoods delineated by ritual poles and strings. Leila interviewed me extensively. As a “native informer,” I initiated her into the intricate and controversial world of eruv building. For my part, I learned about the distinctively rich texture of Parsi life. As I listened to Leila’s descriptions of her family-centered community, with its emphasis on education, drive, and success, and the intertwining of ritual and food, it began to sound familiar. Knowing she had done considerable field work in South Mumbai, I sent her an e-mail when the attacks struck to check that she was safe. I was relieved to learn that, although shaken, she and her family had escaped harm.

One or Two?

My observations about the similarities between Jews and Parsis are not the product of a private idiosyncrasy. Indians often refer to Parsis as “the Jews of India” – something of a misnomer, since Jews have been in India longer than Parsis. Recent writings on Zoroastrianism abound with comparisons to Jews and their exilic communities. And in certain respects, the Parsi story resembles the Jewish American one. As for the longue durée, Jewish history has been intertwined with its Zoroastrian counterpart for thousands of years.

Still, from a theological perspective, Jews and Zoroastrians could not be more different. Judaism is the classic expression of monotheism; Jews believe in a single, exclusive divine power, who is worshipped though the performance of commandments and the avoidance of sin. Zoroastrianism, on the other hand, is quintessentially dualistic. Two powers, the good Ahura Mazda (“Lord Wisdom”) and the evil Angra Mainyu (“Evil Spirit”), face off in a millennia-long cosmic battle. The duty of good Mazdayasnians – or worshippers of Mazda, as Zoroastrians are also known – is to fight for goodness and oppose evil in its many permutations, including falsehood, impurity, and insects.

If we take a closer look, however, this apparent dichotomy is not nearly so stark.

Jews and Zoroastrians met in the wake of Cyrus the Great’s conquests of Judea and Mesopotamia in the mid-sixth century BCE. As the first Persian emperor, Cyrus had a pragmatic, even pluralistic approach to the many religious communities and temples dotting his vast new empire. Cyrus’ own religious convictions seem to have included worship of Ahura Mazda as well as fire – a central Zoroastrian precept. Two generations later, Darius I had an inscription carved in a rock not far from Kermanshah, in Western Iran. There, in Old Persian, the king declared his allegiance to Ahura Mazda, to whom he felt he owed his kingdom. In typical Zoroastrian fashion, Darius’ archenemy is presented as none other than The Lie – the conceptual counterpart of Angra Mainyu.

The earliest source relating to the Jewish-Zoroastrian encounter depicts it as a clash between monotheism and dualism. In addressing Cyrus’ conquests of the Near East,the prophet Isaiah has this to say:

Thus said the Lord to Cyrus, His anointed one, whose right hand He has grasped, treading down nations before him…. I am the Lord, and there is none else; beside Me, there is no god; I engird you, though you have not known Me…. I form light and create darkness. I make weal and create woe – I, the Lord, do all these things. (Isaiah 45:1, 5, 7)

According to the famous Cyrus Cylinder, the chief Babylonian god Marduk chose Cyrus to bring peace to the Babylonians. Similarly, as reflected in the biblical passage above, Judaism viewed the Persian destruction of Babylonia as an opportunity to reconstruct what had been destroyed. Cyrus had the power to bring the Jews back to the Land of Israel and, as he did for Marduk, to help rebuild their Temple. From the prophet’s perspective, however, there was a problem. Since Cyrus did not recognize the Jewish God, nor did he understand the cosmic significance of his conquests, he required a lesson in Monotheism 101. Isaiah 40–48 presents itself as a kind of theological primer addressed to Cyrus, and it does not mince words: The Jewish God is exclusive and all-powerful. He is the Creator of heaven and earth and everything therein. Most important, this God is responsible not only for all that is light and good, but for darkness and misfortune as well. When the verses from Isaiah are juxtaposed with parallels from the Avesta – the Zoroastrian sacred texts, which were transmitted orally from as early as the second millennium BCE – a fascinating mirror effect emerges. The attributes associated with Ahura Mazda in the Avesta are defiantly attributed to Isaiah’s God, but while the Avesta does not hold Ahura Mazda responsible for misfortune, the God of Isaiah 45 proudly associates His name with “woe.” This early intersection was to set the tone for future interactions between Jews and Zoroastrians. Interestingly, unlike the polemics against other cults found in the Later Prophets, which include parodies of icon production and idol worship, the Jewish-Zoroastrian encounter took place primarily in the intellectual and theological spheres.

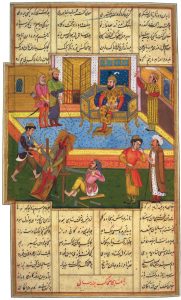

The victories of Darius I are depicted on a monument in Behistun, Iran. This section shows Darius, at center, facing his captives. The inscription proclaims Ahura Mazda as the deity who granted Darius his kingdom

From the Scroll of Esther to the Dead Sea Scrolls

Cyrus did not finish building the Second Temple, but the process was indeed completed under Persian auspices, as we read in the biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah. One might have expected the dispatches between Persia and Yehud – the Persian designation for the Land of Israel at that time – to provide a fascinating window into Jewish-Zoroastrian relations, yet this is not the case. Just as we find in the Cyrus Cylinder, Persian pragmatism and “secular” bureaucracy ruled the day. On the other hand, despite its many historical problems and the total absence of references to divinity, the book of Esther preserves some intriguing fragments of the Jewish-Zoroastrian encounter.

Zoroastrianism is to be found first and foremost in the theophoric names (i.e., those including the name of a god) of some of the book’s main characters. Typical of Zoroastrianism, many of these appellations express concepts deified in the Avesta. For example, the name Mehuman derives from Vohu Manah, which means “Good Mind.” Fascinatingly, in the Zoroastrian pantheon, Vohu Mana is one of the seven Amesha Spentas, or beneficent immortals. This parallels Mehuman’s position as one of Ahasuerus’ seven eunuchs. Another reference to the Mind can be found in the name of the arch villain, Haman, which seems to come from hammanah – “of like mind.” As Harvard scholar James Russel has put it, rulers in all times and places tend to cherish yes-men. Haman’s father, similarly, is Hammedatha, which means “of the same dat,” or law. Indeed, it seems that the use of the word dat (source of the Hebrew term dat – religion) throughout the book of Esther subtly critiques the seemingly arbitrary rule of law in Persian and Zoroastrian culture.

Once we reach the Second Temple era, Jewish literature and thought shifts dramatically. Emphasis is placed on the afterlife, eschatology, and the soul – now a battleground of good versus evil. These ideas dominate Zoroastrianism and how Zoroastrians perceived reality. Nowhere in ancient Judaism is this new dualism stronger than at Qumran, where the sect responsible for composing the Dead Sea Scrolls contemplated the end of history and the ultimate war between good and evil. In numerous Second Temple texts – including the scrolls – evil is seen as separate from God, and opposing Him. Satan and his cohorts develop into a full-blown maleficent force. The demon Ashmedai debuts in Jewish tradition in the book of Tobit, written in the second century BCE. Unlike his more playful talmudic counterpart, this character is lustful and dangerous. In the literature of the Second Temple period, Jewish monotheism veers closer to dualism than ever before.

Surprisingly, this trend takes place at a point when there was little direct contact between Jews and Zoroastrians. Alexander the Great had already defeated the Persian armies during the fourth century BCE; subsequently, Hellenist forces ruled Judea as well as most Iranian lands. In fact, one of the greatest mysteries of ancient Jewish intellectual history is how Second Temple Jews, and particularly sects living in relative isolation, seem to have engaged in a protracted dialogue with Iranian ideas. However this encounter came about, its far-reaching effects on the development of Judaism are indisputable.

The Faravahar symbol has come to represent the Zoroastrian religion over the centuries, although opinion is divided as to whether it depicts Ahura Mazda or the “ancient souls” also revered by Zoroastrians. Wall painting from a fire temple in Taft, Iran

The Sasanian Talmud

Not long after its completion in the fifth or sixth century, the Babylonian Talmud became the most influential text in Judaism besides the Bible. Its authority was of course assumed in Babylonia, but in time the Talmud’s influence spread to North Africa and Europe as well. Because of this profound impact, a proper understanding of the Talmud is essential not only for historians of Babylonian Jewry, but also for scholars of subsequent periods of Jewish history. The question of how to define the voluminous tome that graces the Jewish bookshelf to this day affects how Jewish practice, theology, and culture – which derive largely from the Talmud – are to be understood.

This basic definitional problem has puzzled Talmud scholars and historians for centuries. On the one hand, despite its name, the Babylonian Talmud is preoccupied with the Land of Israel and is a commentary on and repository of Palestinian rabbinic texts. It explains the Mishna, compares it to the Tosefta and other early rabbinic works, and transmits the opinions of the Sages, many of whom dwelt in Palestine. Yet a perusal of its pages indicates that it was firmly grounded in Babylonia. The talmudic rabbis are fiercely loyal to Babylonia, even boasting of their particular towns and villages. The challenges of living under the Roman Empire – which had destroyed the Temple and persecuted the Jews – are mentioned, but only from a distance.

Babylonian Jewry and the Babylonian Talmud were first and foremost citizens and products of the Sasanian Empire – named for the Persian dynasty that ruled a vast expanse of territory from Mesopotamia in the west as far as the Indus region in the east between the third and seventh centuries CE. Zoroastrianism was an important facet of Sasanian identity. The coins minted by this empire typically depicted, on the flip side of a bust of the emperor, a fire altar administered by Zoroastrian priests. Many of the officials in charge of day-to-day legal and financial affairs were also Zoroastrian priests. Along with Christians, Mandaeans, and Manichaeans, Zoroastrian laymen made up a sizable religious community in Mesopotamia. Thus, understanding the Babylonian Talmud requires a deeper appreciation of the Zoroastrian-Jewish encounter in Babylonia.

There is evidence that Jews living under the Sasanians were harassed on occasion, but in comparison with other eras and cultures, this mistreatment was mild. The Jews were also not the only community occasionally persecuted by zealous Zoroastrian priests. A third-century inscription by the Zoroastrian high priest Kirder boasts of the various religious communities made to suffer under his tenure. These included Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, and Manichaeans – adherents of a new dualistic religion founded by a Babylonian named Mani. For most of the Sasanian period, Manichaeans were deemed a major threat to Zoroastrianism. Christianity, too, was seen as problematic, especially after the Roman Empire accepted it as the official religion in the fourth century CE. Sasanian Christians, rightly or wrongly, became associated with the Roman enemy. Descriptions of the resulting mass persecutions have been preserved in a substantial library of martyrologies that recount the suffering of Christians dying for their religion.

Playing with Fire

From what we can gather from the Talmud, the harassment of the Jews was neither systematic nor directed at Jews for being Jews. Instead, the authorities occasionally took aim at rituals that offended Zoroastrian sensibilities. For instance, Hanukkah lamps were confiscated by Zoroastrian fire worshippers lest Jews treat the sacred flames with insufficient respect. The custom of lighting Hannukah lamps on the table rather than in the window, observed in some circles, is a product of this clash with Zoroastrianism.

One talmudic source lists three decrees enacted by Zoroastrian priests against the Jews:

They decreed against three things on account of three things. They decreed against meat because of [the priestly] gifts; they decreed against bathhouses because of ritual immersion; they exhume the dead because they rejoice on the day of their festivals. (Yevamot 63b)

The passage searches for a theologically “measure for measure” explanation for these decrees. Why had God allowed the Zoroastrians to ban ritual slaughter (shehita)? Because Jews had not donated the cuts designated for their own priests, the Kohanim. Why were the bathhouses and mikva’ot shut down? Because Jews had neglected the laws of ritual immersion. Based on our knowledge of Zoroastrianism, however, each of the activities banned would have offended Zoroastrians. Jewish ritual slaughter is diametrically opposed to the Zoroastrian practice of strangulation. (The flow of blood onto the ground is problematic, since Zoroastrians consider the earth sacred.) Indeed, a Zoroastrian work known as the Dēnkard complains about Jewish slaughter of calves. As for immersion, Jewish law requires that married women immerse in the mikve – water from a natural source – following their menstrual period, thus defiling water, another element revered by the Persian faith. Fascinatingly, a midrashic Aramaic translation of the book of Esther known as Targum Sheni claims that this was one of Haman’s complaints to Ahasuerus! Finally, interring the dead also violated the sacred status of the earth. Additional talmudic passages and Christian parallels reflect Zoroastrian efforts to remove corpse impurity from the earth. Zoroastrian law prescribed a ritual wherein the body was placed high on a bier and consumed by birds. To this day, one can see such a place on the outskirts of Mumbai. It is known as the Tower of Silence.

Ateshgah (“Seat of Fire”) fire temple, built in the 17th and 18th centuries in a suburb of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. It is unclear whether this place of worship was originally Zoroastrian or Hindu

A Source for the Gartel

As significant as these anti-Judaic decrees may have been, they were only one aspect of the Jewish-Zoroastrian encounter during talmudic times. There were periods in which curious Sasanian rulers organized “interfaith activities,” including their Jewish subjects as well. These meetings were held in a structure known as the Bei Abedan. The Talmud records that many rabbis invented excuses to avoid such gatherings, although Shmuel, a major talmudic personality, was said to have put in an appearance.

We do not know what was discussed in the Bei Abedan, but some brief theological exchanges preserved in the Talmud may give us a clue. Not surprisingly, one such passage returns to the old monotheism-dualism debate:

A magus said to Amemar [a talmudic sage]: From your waist upward belongs to Ohrmazd [Ahura Mazda, the Force of Good]. From your waist downward belongs to Ahrimen [Angra Mainyu, the Evil Spirit]. [Amemar] said to [the magus]: If so, how does Ahrimen let Ohrmazd pass urine through his land? (Sanhedrin 39a)

At stake here is not only the concept of dualism, but also the way it might be mapped onto this world. Does the body, including the half that produces waste, represent one unified organism, as Amemar saw it? Or are the upper and lower regions divided and ruled by positive and negative forces, as the magus claimed? Although the passage presents the two sides of the debate as irreconcilable, the Zoroastrian approach seems to have left an impact. Elsewhere in the Talmud (Zevahim 19a), the Sasanian king Yazdegerd encourages Huna son of Nathan to adjust his belt. In Zoroastrianism, this article of clothing is highly symbolic: by dividing the upper and lower parts of the body, the belt keeps evil at bay, as it were. To this day, some Jews don a special belt, or gartel, when they pray, echoing a similar conception of the body.

The encounter with Zoroastrianism seems to have influenced other aspects of Jewish thought as well, including essential questions such as the role of destiny in man’s lot. There is also evidence that Sasanian legal notions were utilized – including the Talmud’s claim that a temporary gift constitutes a gift. Furthermore, Zoroastrian mythology and narrative motifs had a major effect on talmudic storytelling. These topics are all related to a relatively new area of academic research, known as Irano-Judaica.

In the seventh century, the Sasanian Empire fell to a conquering Arab army. Over the following centuries, many Zoroastrians converted to Islam, and in the 1800s, a large number of committed Zoroastrians immigrated to India. At that time, the Babylonian Jewish community intersected most interestingly and productively not with Zoroastrianism, but rather with Islam. For Jews and Zoroastrians alike, the influence of Islamic philosophy – with its roots in Greek thought – was profound. Gaonic and post-Sasanian Zoroastrian works both bear unmistakable traces of this new encounter. One Persian source worth mentioning depicts a disputation between a Zoroastrian priest and a Zoroastrian convert to Islam, held in front of the caliph al-Ma’amun (ruled 813–33). One of their debates concerns the anatomical dualism discussed by Amemar and the magus centuries earlier. The terms of the new debate are almost identical to those appearing in the Talmud, but the introduction of philosophical concepts and argumentation adds color.

While the encounter between Judaism and Zoroastrianism mostly disappeared from the public sphere after the Islamic conquest, in communities where Jews and Zoroastrians lived side by side it continued, particularly in the domestic context. Iranian Jews, like their Muslim neighbors, continued to celebrate Nowruz, the (pre-Islamic) Persian New Year, with colorful spreads of symbolic foods. To this day, the traditional seven dishes are laid out on a carpet, and the family gathers around to share in the spring feast. What is more, some families burns esphand, or wild rue, in a golden brazier while everyone dines. Ritual fire has thus come full circle, returning to the Jewish home through an appropriated Zoroastrian ritual. In its own way, the esphand encapsulates the Jewish encounter with Zoroastrianism, which continues to burn brightly.

—

Good vs. Bad

Zoroastrians live in a world divided.

The Superpowers

The force of good, Ahura Mazda (Lord Wisdom), and the force of evil, Angra Mainyu (the Evil Spirit) are locked in eternal conflict

Head over Heels

The upper part of the body is ruled by positive powers, while the lower half is controlled by negative forces. The two halves should be separated by a belt or girdle.

Fighting the Fight

A good Zoroastrian fights on the side of good and opposes evil in its various forms, which include lies, impurity, and insects

Silver drachma issued by Ardashir III, one of the last monarchs of the Sasanian dynasty, c. 630

–

High Tension

Various elements and beings are sacred to the Zoroastrian faith: fire, water, earth, plants, cattle, and the priest or holy man. This resulted in a number of areas of tension between Jewish law and its Zoroastrian counterpart:

Burial

Instead of burying the dead in the sacred earth, Zoroastrians lay corpses on a high, exposed platform, to be consumed by birds of prey. There were periods when Zoroastrian priests exhumed Jews and Christians from their graves to prevent them from defiling the earth.

Animal Slaughter

Zoroastrians kill animals by strangulation. The Jewish method of cutting the windpipe is unacceptable to them, as is the practice of allowing the blood to flow onto the ground, as required by Jewish law.

Immersion

Menstruating women are ruled by the forces of evil, according to Zoroastrian belief, and are therefore expected to keep a distance from their families. Their purification process involves rubbing their bodies with bull urine. By submerging herself in water, an unpurified woman would transfer her impurity to the sacred liquid, so the immersion of Jewish women in a mikve is anathema to Zoroastrians.

Ritual Fire

Fire plays a vital part in Zoroastrian ritual. Therefore Zoroastrians opposed the use of fire in private rituals performed by non-believers, such as lighting candles at the beginning of the Sabbath, or kindling Hanukkah lamps.

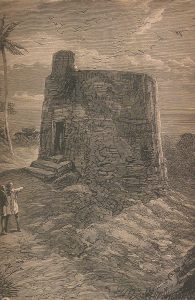

Ridding the earth of impurity. The Tower of Silence, Mumbai. Traditionally, bodies were left here to be consumed by birds of prey. Engraving from True Stories of the Reign of Queen Victoria, by Cornelius Brown, 1886

–

Well-Known Zoroastrians

Zubin Mehta, the world-famous conductor from Mumbai, is also musical director of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

Rohinton Mistry, an Indian-born Canadian author, writes in English. His books, widely translated, include A Fine Balance and Family Matters

Homi K. Bhabha, a sociologist, research fellow, and author, was born in Mumbai and lives in America. He is a well-known post-colonialist thinker