Self-Imposed Boundaries

In 1946 a young Jewish veteran, Aaron Frankel, returned from the army to Manhattan’s Upper West Side only to discover that the fashionable Jewish neighborhood where he had grown up no longer felt like home, despite its Judeocentricity. “What had I come back to?” Frankel asked in an essay in Commentary that year.

Frankel had returned not only to the most Jewish city in the United States, but to what he called the “most compact and prosperous Jewish community in the city of New York.” At mid-century, Eighty-Sixth Street was the epicenter of New York’s Jewish world.

American Jews have created models of Judaism attuned to American culture and values. A prayer service for the success of American soldiers on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Mostly women attended – able-bodied men were at the front

Yet for Frankel – as for many Jewish veterans – the Upper West Side felt stifling, its concerns parochial. “Eighty-Sixth Street Jews still feel themselves in exile,” he wrote. “Perpetually they fret that they do not yet ‘belong,’ and are not yet ‘accepted.’” Increasing acceptance and integration of Jews and Judaism in America in the late 1940s and 1950s made veterans self-conscious about what felt like the self-imposed boundaries of Jewish neighborhoods. In the army, Jews had found that “if they made no point of being special, or different, neither did anyone else.” Thus, many Jewish men rejected segregated Jewish life in urban enclaves like New York. In fact, some posited that living such cloistered lives might actually cultivate Jewish insecurity. “Can it be that our sense of the Jewish Problem is induced as much by our narrow manner of living as by external pressure?” Frankel worried that his coreligionists had not so much left the ghetto as “transformed and gilded it.”

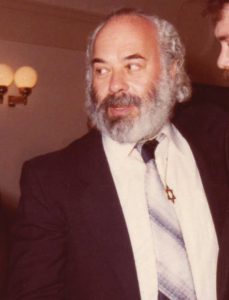

Coming home. Jewish soldiers fought long years alongside their compatriots in the Second World War. Returning to New York, many of these veterans helped found branches of Judaism suited to their new way of life

While Frankel considered demonstrably Jewish neighborhood his parochial and stifling, it in fact represented progress. When Jewish refugees arrived in New York in 1654, its anti- Semitic governor, Peter Stuyvesant, wanted to keep them out. Although Stuyvesant’s Dutch superiors overruled him, he restricted Jews from building a synagogue and demanded that they practice their religion only at home. Thus, although the city’s (and the country’s) first congregation, the Spanish and Portuguese Shearith Israel, was founded in 1654, New York Jews secured the right to worship in public and open their first synagogue only in the 18th century.

New York’s second-oldest synagogue, the famous B’nai Jeshurun, was founded in 1825 as an Ashkenazic breakaway from Shearith Israel. In 1829, Ansche Chesed (now a large, Conservative synagogue on the Upper West Side) splintered off from B’nai Jeshurun. By 1835, New York had four synagogues; by 1845, there were ten; and by 1855, over twenty. The desire to maintain unity no longer restrained congregants from expressing dissatisfaction, and the need to attract new members further motivated congregations to adjust their practices. In the mid-19th century, Reform Judaism was introduced to New York as young German immigrants sought to add more dignity and decorum to the synagogue. The desire to win greater Jewish respectability among non-Jews in New York inspired many new Jewish leaders and movements as well.

Congregational autonomy became the new norm for New York Jews, and a monolithic American Judaism was replaced by numerous synagogues and styles of worship. As no single synagogue represented the New York Jewish community, community wide organizations were established to transcend the differences. Meanwhile, a democratic and diverse American Judaism thrived.

Completing the Spectrum

By the late 19th century, New York was split between Reform and traditional Judaism, although the Reform movement did not move its headquarters from Cincinnati to the Big Apple until 1950. New York’s Jewish religious marketplace was primed for the traditional, non- Reform group of Jews who founded the Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary Association (JTS) in 1886. “Non- Reform” aptly describes these early supporters of the movement. They had an affinity for tradition but did not feel bound by it, and they wanted to discourage assimilation and attract eastern European Jewish immigrants repelled by the radicalism of Reform. As an opponent of Reform, Conservative Judaism even enjoyed Orthodox backing for a while. Particularly since the mid-20th century, the Conservative movement has sought to shed its “non-Reform, non-Orthodox” image.

Historically, talented leaders have provided much of the movement’s direction. Solomon Schechter reorganized JTS and embodied the blend of eastern European traditional Judaism and secular learning that Conservative Jews valued. So respected was Schechter that even lay leaders within New York’s Reform movement rallied behind his seminary. In the 1960s, JTS professor Abraham Joshua Heschel steered Conservative Judaism toward social justice and the civil rights movement. Schechter and Heschel, both bearded, looked like traditional eastern European scholars but tackled the issues of the day, combining old and new in classic Conservative style. The lack of such leaders today may explain why so many young New Yorkers have turned to nondenominational options. Just as “non-Reform” once signaled a generation’s disdain for the Judaism of older, more assimilated Jews, “nondenominational” today suggests a younger generation’s dissatisfaction with the perceived compromises of its forebears.

Prof. Abraham Joshua Heschel (second from right) of the Conservative movement, marching with Martin Luther King (center)

In 1915, the Orthodox movement founded its seminary in New York, completing the spectrum of rabbinical studies in the city. By the 1920s, American Jews and Judaism had shifted from a nationwide phenomenon, with a sizable presence in New York City, to a group overwhelmingly concentrated in the northeast, with almost half its members in New York.

Charismatic and talented rabbis have also shaped New York’s Jewish diversity. In the 1970s, the rabbi and composer Shlomo Carlebach, known as “the singing rabbi,” reinvigorated the Upper West Side synagogue led by his father (a German-born Orthodox rabbi) through his unique blend of Hasidic Judaism, personal warmth, and music. Lincoln Square Synagogue also benefited from a dynamic rabbi, Shlomo Riskin, under whose leadership it shifted from Conservative to Orthodox in the late 1960s and augured the rejuvenated Orthodoxy of the 1970s. Though famous for its singles scene, Upper West Side Judaism caters to Jews of all ages.

carlebach.net, courtesy of the Carlebach Legacy Project

carlebach.net, courtesy of the Carlebach Legacy Project Orthodox if unconventional, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, the Woodstock Rabbi of the swinging Sixties

New York’s non-Orthodox synagogues specialize in social action, Torah study, and communal Shabbat dinners, supplementing these “staples” with such a variety of educational and cultural opportunities that Jews throughout the country look on with awe and envy. Brooklyn, always the most Orthodox borough of New York, has seen a non Orthodox revival. Rabbi Andy Bachman of Park Slope leads one of many liberal, progressive Brooklyn synagogues. Even the West Side’s B’nai Jeshurun, associated with various denominations throughout its long history, has been unaffiliated for the past ten years – a status much favored by a generation turned off by its parents’ bland suburban Judaism.

Born in Borscht

What also makes New York Jewish life special is that even the unaffiliated feel Jewish just by being in the city. As Lenore Skenazy wrote in the Forward (February 17, 2010):

In New York, Jews are practically born in borscht. From babyhood they’re swimming in ethnicity, from bagel stores to Brooklyn’s Boro Park to Broadway – so much that they don’t even notice. And they’re always just a subway ride away from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, our ancestral gateway to America.

Just as Israeli Jews are known among non-Israelis for their secular Judaism, New York Jews have a history of strong, cultural Judaism. The “Israel of America,” New York has come to seem like the Jewish homeland within the United States. The city’s historic Jewish landmarks – Ellis Island, the Lower East Side, the Statue of Liberty, Coney Island – evoke unreserved nostalgia among American Jews (which Israel increasingly does not).

But to Frankel, and other mid-century commentators, the all-encompassing quality of New York Judaism degraded its content. “Eighty-Sixth Street’s Jewishness,” noted Frankel, “may mean anything from a powerful religious feeling to mere anti-defamation support, it may be a political or an ethical idea, or it may mean nothing definite at all.” Even Mordecai Kaplan’s Reconstructionism – a denomination born and bred on the Upper West Side – which had once seemed such a hopeful sign of Jewish survival in modern America, “now seems to me to be based too much on what are largely ghetto premises,” Frankel reflected.

It was on Eighty-Sixth Street that Kaplan, one of America’s great 20th-century theologians, first set up shop, envisioning the Orthodox Jewish Center there as a place that “would bring Jews together…for social, cultural, and recreational purposes in addition to worship.” Kaplan’s ideas proved too radical for the “JC,” however, so he moved down the street to found the Reconstructionist Society for the Advancement of Judaism in 1921, where his daughter Judith famously celebrated the first bat mitzva, in 1922. Once a fringe movement, Reconstructionism now actually characterizes most of non-Orthodox American Judaism. That is, them movement’s egalitarianism and lack of supernaturalism have become mainstream, as has its view of Judaism as an evolving civilization in which halakha is not binding.

Unity in Diversity?

For Orthodox-born Mordecai Kaplan, who taught at the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, Reconstructionism represented that part of Judaism that “all Jews have in common.” Although the philosophy ended up as its own branch of Judaism, his original idea that it be an overarching, umbrella movement emanated from a unity of Jewish denominations that seemed utterly attainable in New York in the first decades of the 20th century. By 1945, when New York Orthodox rabbis publicly burned the prayer book he had published and excommunicated him, Kaplan must have realized that such unity was unlikely. Eighty-Sixth Street still bears the imprint of two of his creations, symbols of the kind of religious quest that seems possible only in New York.

To Jews like Frankel, however, it was suburbia that felt young, cosmopolitan, adventurous, and conducive to postwar Jewish life. While Orthodox and especially Hasidic Jews tended to stay in the city, Reform and Conservative Jews believed the suburbs were healthy environments for growing their communities, while urban Jewish neighborhoods had the stale, musty feeling of a grandparent’s apartment. No wonder, then, that when Frankel returned to the Upper West Side, he reported “a sinking of heart and an oppression of spirit at horizons suddenly narrowed and a world so cozy and selfabsorbed.”

For Frankel, being Jewish in New York meant suffering from “a universal and deadly inner insecurity, a desperate want of self-respect. In some cases, and under the impact of certain events, the condition verges on panic.” It is difficult to understand how someone writing so soon after the Holocaust could be so unsympathetic to his coreligionists’ instinctive desire for safety in numbers. Yet to him and others of his ilk, the New York Jewish community felt like an echo chamber of anxiety.

Although the American ultra-Orthodox movements are generally thought to be more integrated into society than their equivalents in Israel, this 2012 rally against Internet use at the New York Mets stadium showed otherwise

Revitalized Jewish Appeal

In an almost total reversal of Frankel’s aversion to Jewish insularity, the Upper West Side and Brooklyn are now increasingly popular places for Jews to live and revitalize their religion. Brooklyn has been transformed “from suburb to shtetl,” to quote sociologist Egon Mayer, particularly in Boro Park and Williamsburg. More and more restaurants, stores, and hotels cater to Orthodox Jews.

Brooklyn embodies the increasingly Orthodox feel of Jewish New York. The 1994 construction of an eruv – a symbolic boundary that allows carrying on the Sabbath – is one sign of the growing Jewish religious presence on the Upper West Side.

Even among the Orthodox, however, diversity prevails. New York’s Orthodox community is a divided one, particularly when it comes to threats posed by other Jewish movements and external American culture. At a rally of ultra-Orthodox Jews to discuss the risks of the Internet in May this year, tens of thousands of Jewish men – a sea of black suits and white shirts – filled a New York baseball stadium. The New York Times reported:

The gathering may have felt like a “gigantic family reunion,” but the comments of one participant revealed the atomized nature of New York Orthodoxy. “It may look like a community because we all look the same,” said one participant. “But I don’t know almost any of the people here.”

Orthodox Jews are represented by a variety of organizations. The Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America (known as the OU) and the Rabbinical Council of America represent modern Orthodoxy, whereas Agudath Israel speaks for the Haredi (ultra- Orthodox) community. Chabad-Lubavitch is a branch of Hasidic Judaism well-known to American Jews because of its intensive outreach efforts, especially on campuses. And then there are sundry Hasidic sects, from Skver and Bobov to Satmar and Vishnitz, for which no organization can claim responsibility.

A common denominator of all these diverse groups is the famous New York dating scene. The out-marriage rate has remained lower in the city than in the country at large. New York has always afforded young Jews more dating choices than anywhere else, and that has continued to fuel a large post-college migration to the city.

Thus, half a century after Frankel returned home and recorded his feelings about the Upper West Side, Judaism in New York, far from “becoming nothing,” is as vibrant as ever. Newly released statistics show a ten-percent growth in the city’s Jewish population over the last decade. In short, New York’s status as a Jewish center has been as dynamic as the city itself.