[To hear this article on our podcast please click here]

Gateway to the Empire

In 1492, four hundred glorious years of Spanish Jewish literature and culture abruptly ended. The land that had nurtured brilliant Jewish legalists, philosophers, mystics, poets, and grammarians began to heave and tremble beneath the ancient Jewish community. Fearing for their lives and livelihoods, many converted to Christianity, emulating their leader, Rabbi Abraham Senior. But for a multitude of others who clung to their faith, the only option was to leave Spain.

Some settled in nearby Portugal, only to be forcibly baptized in 1497. Some crossed the narrow stretch of sea to North Africa, while others sought out less hostile shores on the Mediterranean, such as those of Christian Italy and Holland. Not all these Jews were welcome, as their contemporary Solomon ibn Verga wrote:

The Spanish exiles’ ships reached Italy, and there too, great famine was everywhere, and plague raged onboard. The poor souls knew not what to do […] until finally they disembarked. But the townspeople wouldn’t grant them entry. So they went to Genoa, where there was also famine, but they were allowed into the town.

Unable to abide their suffering, the young men went to the house of idolatry to convert just so they would be given a little bread. Many of the uncircumcised walked through the markets with a crucifix in one hand and a morsel of bread in the other, bidding the sons of Israel: “If you bow to this, here is bread.” In this fashion, many became apostates and intermingled with the non-Jews. (Solomon ibn Verga, Shevet Yehuda [Scepter of Judah] [Amsterdam, 1654], p. 62a [Hebrew])

But as one door closed on the Spanish exiles, another unexpectedly opened. Sultan Bayezid II, ruler of the Ottoman Empire, unlocked the gates of his realm, either in anticipation of the benefits these talented merchants could bring to his economy, or in response to pressure from Jewish leaders in Turkey. Regardless of his motives, a firman (royal edict) ordered Ottoman governors to receive all Jews kindly.

The refugees arrived penniless and sometimes – not unlike Holocaust survivors – without a clue as to what had become of their nearest and dearest. They soon viewed the Ottoman Empire as their new homeland. Nevertheless, despite their suffering at the hands of Spain’s Christian monarchs, these Jews always considered themselves Sefaradim, Spanish.

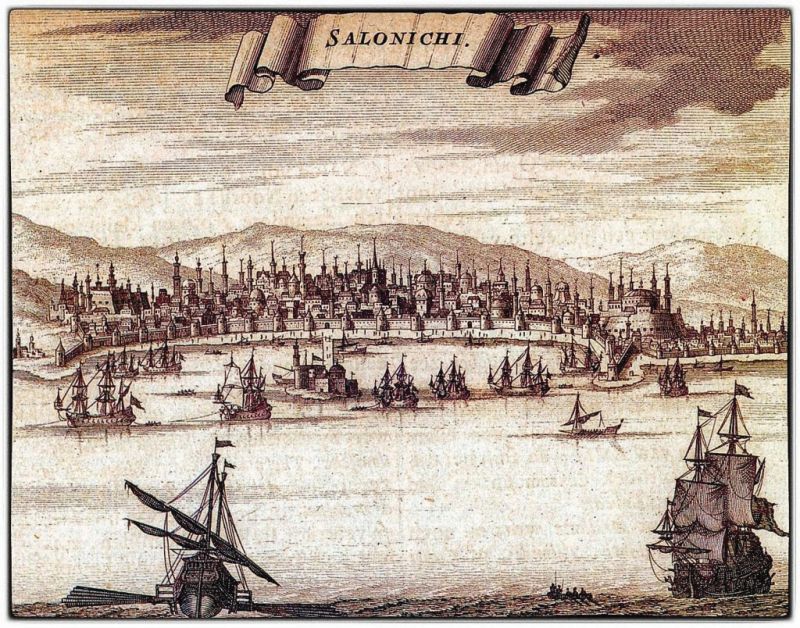

Of all their destinations, the port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki), western gateway to the empire, was unique. The cosmopolitan city was a melting pot of Turks and Greeks, Bulgars and Macedonians, Slavs, Russians, and even Frenchmen. Thousands of Jews who’d been there for generations mixed with newcomers from Germany, Italy, and North Africa. Salonika’s strategic location on the Mediterranean was also not far from Spain, making it literally a lifesaver for Spanish exiles, who could otherwise have been stranded at sea indefinitely.

Mother Salonika

A Portuguese poem by Portuguese Jewish author Samuel Usque conveys the overwhelming relief with which those lucky enough to reach Salonikan shores fell into the city’s embrace:

Behold, Salonika, you are a mother city of Israel. A faithful orchard of Jewish law and faith, filled with fair flowers and fine trees, famed for its glory among Israel. Its fruits exude beauty and majesty, for it grows alongside springs of charity, and streaming rivers of kindness and mercy water its soil. The brokenhearted and downtrodden who flee there from European lands and all other parts of the world will find healing and cure. It will absorb them lovingly, like a merciful mother, like the mother of Israel, like Jerusalem on its festivals. (Samuel Usque, cited in Y. S. Emanuel, Leaders of Salonika in Chronological Order, part 1, p. 6 [Hebrew])

Salonika, the Ottoman Empire’s western gateway, as depicted in Braun and Hogenberg’s atlas of the world’s cities, Cologne, 1572

Salonika, the Ottoman Empire’s western gateway, as depicted in Braun and Hogenberg’s atlas of the world’s cities, Cologne, 1572Salonika’s new inhabitants quickly made it a bustling international trading hub. Jews dealt in lead for artillery, wine, spices, and precious stones. The textile business took off, and silver and salt mines were developed. Like most Jewish centers, Salonika became a printing powerhouse as well. Many Jews grew so rich that, just thirty years after the trauma of the Spanish expulsion, Jewish ethical tracts began criticizing their luxurious lifestyle.

A tremendous spiritual renaissance accompanied the economic boom, with Salonika even becoming known as the Balkan Jerusalem. A rare concentration of kabbalists from the Iberian Peninsula gathered in the city: rabbis Yosef Taitazak, Yosef Karo, Solomon Molkho, and Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz. All four endeavored to redeem the Jewish people through various but interrelated methods. What were these paths, and to what extent did they leave a mark on Jewish history?

Practical Kabbala

The eldest of the group was Rabbi Yosef Taitazak, born circa 1465 in Castile. This Portuguese Jewish leader headed Salonika’s largest Talmudic academy. In many ways, Taitazak was the preeminent halakhic authority after the expulsion, certainly as far as the scattered Andalusian communities were concerned. Aside from being a rabbinical judge and preacher, however, he was a philosopher versed in the writings of Thomas Aquinas and many other thinkers. Yosef Karo called him “sage in all matters” (Avkat Rokhel 51).

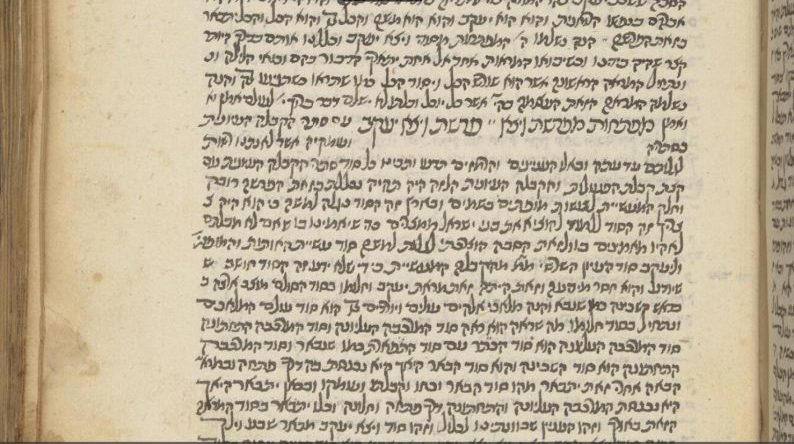

Practical kabbala as a means of revelation. Sixteenth-century manuscript of The Book of the Responding Entity

Taitazak seems to have been part of a kabbalistic circle that coalesced around the author of the mystical Sefer Ha-meshiv (The Book of the Responding Entity), also known as The Maggid’s Book of Visions. Apparently predating the Spanish expulsion, this work discusses the use of specific techniques to summon a divine revelation in the form of an angel.

The secret lies in the fact that the hidden meaning of this number [forty-five, the numerical value of one of the divine names], when uttered in full, will draw down My power and Divinity in the form of an actual man standing before you to answer whatever you would ask in real speech before you, without [causing] terror. (cited in Moshe Idel, “Research on the Method of the Author in The Book of the Responding Entity,” Sephunot 17, p. 215 [Hebrew])

The book describes a group of scholars who magically produce just such a divine manifestation. The best-known tale associated with this cabal involves one Rabbi Joseph De-La Reina’s efforts to employ these methods to hasten the final redemption. Though the story sounds utterly fantastic, Kabbala scholar Gershom Scholem proved that De-La Reina was in fact a historical figure, having contributed to Sha’arei Ziyyon, a collection of ancient and medieval prayers and liturgical poems attributed to a disciple of the renowned Rabbi Hayyim Vital.

De-La Reina and his circle supposedly used kabbalistic incantations to force Satan to appear as a black dog. While his colleagues fled, De-La Reina bound the dog by means of a ring inscribed with the forty-two-letter name of God (which still appears in the Hasidic Sabbath eve liturgy alongside the eight-line poem Ana Be-khoah [Please, by the Strength]). Then Satan broke free and punished the sage who’d dared to restrain him: De-La Reina reputedly either converted or committed suicide.

Led by the legendary Rabbi Isaac Luria (a.k.a. Arizal, 1534–1572), the kabbalists of Safed subsequently outlawed “practical Kabbala,” such as making angels heal or reveal mystical secrets. Rabbi Luria lived in Safed only from 1570 to 1572, but his main pupil, Rabbi Vital (1542–1620), cited De-La Reina’s fate as a cautionary tale:

Take proof from Rabbi Joseph De-La Reina and Rabbi Solomon Molkho, who engaged in practical Kabbala and were cast out of the world. […] Even more reason [to refrain] is that [the angels guarding the gates] must be coerced by oath, against their will. Then they entice [the kabbalists], leading them down unworthy paths until they lose their souls. (Rabbi Hayyim Vital, Sha’arei Kedusha [Gates of Holiness], part 3, gate 6)

Evidently, Rabbi Taitazak wasn’t spooked by such incidents. One work attributed to him is Kaf Ha-ketoret (The Incense Spoon), written after the expulsion and concerned primarily with estimating when redemption is due and bringing it about using kabbalistic meditations on Psalms.

The second cautionary figure mentioned by Rabbi Vital also appeared in Salonika while Taitazak was active. Like him, Solomon Molkho claimed that a heavenly emissary, or maggid, had appeared to him (see Motti Benmelech, “Salvation at Stake,” Segula 33). The similarities don’t end there.

Salonika’s Messiah

Molkho was born Diogo Pires to a converso family in Portugal in 1501. (Despite the forced baptism of Portuguese Jewry in 1497, a strong crypto-Jewish community remained.) In his twenties, Pires served as a senior lawyer in the royal court in Lisbon.

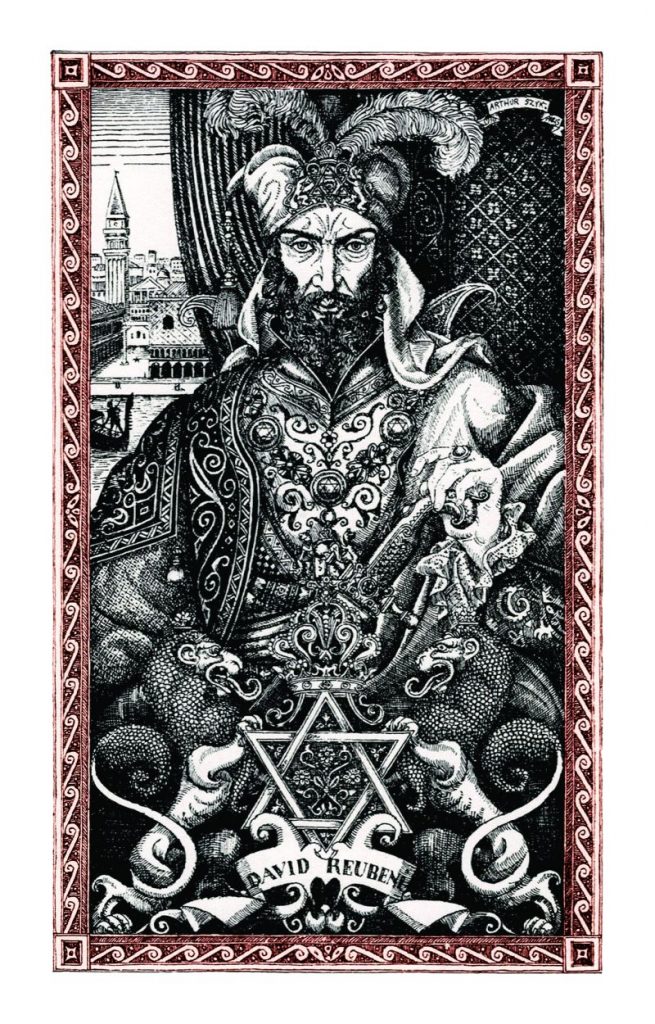

Molkho’s messianic pretensions led to his death at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition but also made him a hero. Molkho’s standard, inscribed with biblical verses, preserved in the Jewish Museum, Prague

Molkho’s messianic pretensions led to his death at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition but also made him a hero. Molkho’s standard, inscribed with biblical verses, preserved in the Jewish Museum, PragueA few hundred kilometers away in Italy, a sensational series of events was under way. Short, swarthy David Ha-Reuveni had miraculously gained access to Pope Clement VII in Rome in 1524. Purporting to be commander in chief of the armies of his brother, ruler of the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh in a distant Arabian kingdom, Ha-Reuveni persuaded the pope to assist him in conquering Mecca! The pontiff sent him on to John III of Portugal, recommending that the king assign him additional troops.

The arrival of this colorful character in Portugal excited the country’s crypto-Jews. Diogo Pires, for one, resolved to return to Judaism. Ha-Reuveni refused to circumcise him, however, fearing accusations that his true mission was to reclaim Portugal’s New Christians, as the Jews were known. Undeterred, Pires performed the operation himself (though he almost bled to death), changed his name to Solomon Molkho, and fled to either Italy or Salonika in 1525.

In 1529, Molkho published Sefer Ha-mefo’ar (The Magnificent Book), a surprisingly erudite book of mystical sermons. As he wrote in his prologue, the work was intended

“For my dear brothers and friends in Salonika, who asked me to send them some interpretations of the true path, or commentary on the weekly Torah portion, or sayings of our sages, may they rest in peace.”

What brought Molkho to Salonika? Having written to Yosef Taitazak, perhaps he’d heard of the rabbi’s mystical revelations and hoped to find him a kindred spirit. Alternatively, Taitazak may have summoned Molkho, hoping their encounter would reawaken his own mystic visions after they’d ceased following the Spanish expulsion. Whatever the case, the two had much in common – including a determination to hasten Israel’s redemption through kabbalistic means.

Molkho resided in Salonika sometime between 1526 and 1529. There he met Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, who was born in the city in 1505 and wrote of scriptural interpretations heard from him. But then, having printed his sermons, Molkho left for Italy.

Like David Ha-Reuveni, Molkho foresaw redemption coming about through world conflict, which he duly tried to set in motion. He regarded himself as the Messiah son of Ephraim, harbinger of the true Messiah, son of David. Molkho joined Ha-Reuveni in the summer of 1532 for a meeting with the holy Roman emperor, Charles V, who also occupied the Spanish throne. They urged him to order the armies of Europe to attack the Ottoman Empire, instigating a war between Christians and Muslims that would constitute the biblical showdown between Gog and Magog prior to the redemption of Israel.

Unlike Pope Clement and John of Portugal, however, Charles promptly handed Ha-Reuveni over to the Spanish Inquisition, and he was never heard of again. Molkho, a lapsed New Christian, was sent to Mantua for trial and burnt at the stake.

Heir to a Mission

Between 1528 and 1531, a fourth scholar arrived at Rabbi Yosef Taitazak’s Talmudic academy. Born in Portugal in 1488, Rabbi Yosef Karo famously authored two classic works of Jewish law, Bet Yosef and Shulhan Arukh (see Tirza Kelman, “Coded for Print,”Segula 44). Yet he came to Greece an unknown, his kabbalistic studies still ahead of him.

Though heavily influenced by Solomon Molkho, Rabbi Yosef Karo chose a different path. 19th-century woodcut portrait of Rabbi Karo

Though heavily influenced by Solomon Molkho, Rabbi Yosef Karo chose a different path. 19th-century woodcut portrait of Rabbi KaroAlthough there’s no clear evidence of direct contact between Rabbi Karo and Solomon Molkho, they overlapped in Salonika in 1529, and Molkho’s influence changed Karo’s life. The two were also close in age and countrymen. At the very least, Karo’s closest friends were profoundly impressed by Molkho.

Rabbi Yosef Karo was devastated by Molkho’s execution. Karo idealized him as an outstanding kabbalist, a prophet, and – above all – a martyr for his people. Shortly after Molkho’s death, Karo too began envisioning a heavenly voice, or maggid, speaking unbidden from his mouth, sometimes personifying the Mishna itself as he recited its passages. Rabbi Karo seems to have believed that Molkho’s soul had entered his own body and that he was to continue his hero’s mission. This heavenly messenger promised the rabbi a “bright” future, including the same martyrdom as “my friend Shlomo” (Rabbi Yosef Karo, Maggid Meisharim [Teller of Truths], 1st ed., “Genesis,” 27 Heshvan).

Why did Rabbi Karo wish such a violent death upon himself? Perhaps like the great Rabbi Akiva, he simply sought to fulfill the biblical injunction to “love the Lord, your God, with all your soul” (Berakhot 61b). Alternatively, traumatized by the previous generation’s expulsion, he might have concluded that God no longer had place for Jews in this world. Similarly, the maggid ordered Karo to minimize his intake of food and water, thus reducing his bodily existence. This second-generation post-trauma may have reflected the collective subconscious of his entire era.

The Shekhina Speaks

Though he’d inherited Solomon Molkho’s mission, Rabbi Yosef Karo chose an utterly different path to redemption. In 1533, a few months after Molkho’s demise, Rabbi Karo and fellow kabbalists (Alkabetz included) studied all night on Shavuot – the holiday marking the revelation at Sinai and hence the wedding of God and Israel – just as described in the Zohar (1, 8a):

Rabbi Shimeon would sit and study Torah all night when the bride was about to be united with her husband [i.e,. on the eve of Shavuot]. And we have learned that the companions of the household in the bride’s palace [i.e., the members of Rabbi Shimeon’s circle of mystics] are needed on that night when the bride is prepared for her meeting on the morrow with her husband [i.e., God Almighty] under the bridal canopy. They need to be with her all that night and rejoice with her in the preparations with which she is adorned, studying Torah, [progressing] from the Pentateuch to the Prophets, and from the Prophets to the Writings, and then to the midrashic and mystical interpretations of the verses, for these are her adornments and her finery. (Isaiah Tishby,The Wisdom of the Zohar, trans. David Goldstein [Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1991], vol. 3, p. 1318)

For probably the first time in history, Rabbi Yosef Karo and his circle sought to reenact this scene. The resulting life-altering revelation was later depicted by Shlomo Alkabetz in a letter reproduced by Rabbi Isaiah Halevi Horowitz in his Shnei Luhot Ha-brit (The Two Tablets of the Covenant), published in 1648 and known by the acronym Shelah. The Shekhina spoke from Rabbi Karo’s lips, praising the small group who’d restored the divine presence while Salonika slept:

Happy are those who bore you, My friends, in that, by denying yourselves sleep you have ascended so far on high. Throgh you I have become elevated this night and through the companions in the great city, a mother-city in Israel.

You are not like those who sleep on beds of ivory in sleep which is a sixtieth of death, who stretch themselves out upon their couches. But you cleave to your Creator and He rejoices in you. (Louis Jacobs, Jewish Mystical Testimonies, Schocken Books, 1977, p. 100)

The Shekhina then lamented its own misery:

If you could only imagine one millionth of the anguish which I endure, no joy would ever enter your hearts and no mirth your mouth, for it is because of you that I am cast to the ground. (ibid.)

Finally, the divine presence suggested a course of action:

Happy are you. Return to your studies, not interrupting them for one moment. Go up to the land of Israel, for not all times opportune. There is no hindrance to salvation, be it much or little. Let not your eyes have pity on your worldly goods for you eat of the goodness of the higher land. If you will but hearken, of the goodness of that land will you eat. Make haste, therefore, to go up to the land for I sustain you here and will sustain you there. To you will be peace, and to all that is yours peace. (ibid., p. 101)

The Shekhina called on Karo and his colleagues to abandon the fleshpots of Salonika for the Holy Land, taking the divine presence with them and thus ending its suffering. This path clearly differed not only from that of Rabbi Yosef Taitazak and the circle of the author of The Book of the Responding Entity, but from that of David Ha-Reuveni and Solomon Molkho. The divine voice speaking from Karo’s throat intimated that redemption would come not through incantations or political intrigue but only through Jews’ physical return to their homeland.

Could this be where Rabbi Karo and his colleagues purified themselves before their fateful night of study on Shavuot in 1533? Surviving the fire that raged through Salonika in 1917, this stone bathhouse is known today as the Yahudi Hamam

In contemporary terms, if Molkho and Ha-Reuveni represent political Zionism, marshaling international forces to create a Jewish nation-state, then Rabbi Yosef Karo and the Shekhina that spoke through him represent practical Zionism, such as that of the pioneer movement of the early 19th-century. Rather than using diplomacy to change the world, they sought to make a difference as individuals, believing that the small steps taken by committed pioneers could eventually make a great impact.

Rising from the Dust

Though their Shavuot night vigil left an enormous impression on Rabbi Karo and his companions, not until three years later – after the death of his wife and three children in a plague – did Karo take ship with Shlomo Alkabetz and other rabbis and their families from Constantinople to the Land of Israel. In his farewell sermon in Salonika, Rabbi Alkabetz remarked:

When [the Talmudic sage] Rabbi Meir [lit. “Shining One”] used to look in his Torah scroll, he saw there that Adam, the first man, lost his raiment [of] supernal light. For after he sinned, he was cursed with the burden of physical matters, [represented by the] skin tunics [provided by God to clothe Adam and Eve]. Through the Torah, however, the original, spiritual raiment could be regained […], and [instead of] “skin garments” [as written in the traditional Torah text], read “garments of light.” (quoted in Reuven Kimelman, The Mystical Significance of “Lekha Dodi” and Kabbalat Shabbat [Magnes Press, 2003], p. 138 [Hebrew])

Lekha Dodi was quickly adopted by almost all Jewish communities and included in the standard prayer book. Tomb of its author, Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, in Safed

Lekha Dodi was quickly adopted by almost all Jewish communities and included in the standard prayer book. Tomb of its author, Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, in SafedAdam’s raiment of skin represented the curse of physical existence, whereas Torah study revealed a spiritual reality – replacing the animal skins with garments of light. For Alkabetz, moving to the Holy Land meant shedding the burdensome skins of physical existence and living a more spiritual, enlightened life. Together with other mystics, including Rabbi Karo, Alkabetz contributed to the kabbalistic renaissance in Safed.

To welcome the Sabbath bride, these kabbalists dressed in white and ventured out to the fields every Friday at sunset. There they attempted to usher in redemption, raising the Shekhina from the dust.

For this ceremony, Rabbi Elkabetz composed the famous liturgical poem Lekha Dodi, whose refrain entreats, “Come, my beloved, to greet the bride.” The Hebrew word orekh (your light) marks the exact midpoint of this hymn, with the middle stanza playing on the Hebrew term or (light), beginning with the letter alef, and its homonym, spelled with an ayin and meaning both “skin” and “awaken” (or literally, “shake off one’s skin”):

Shake off your skin, shake off your sleep,

For your light has come. Arise, shine!

Awake, awake, declaim a song

The glory of God is revealed in you.

In this poem, light is clothed in garments of slumber. Alkabetz returns to the same metaphor used in his parting speech in Salonika, planting it firmly at the center of the ceremony welcoming the Sabbath. Coming full circle, the sons of Salonika shed the false skin of exile and revealed the vibrant, true colors of the Promised Land, greeting the Sabbath and redeeming the Shekhina.

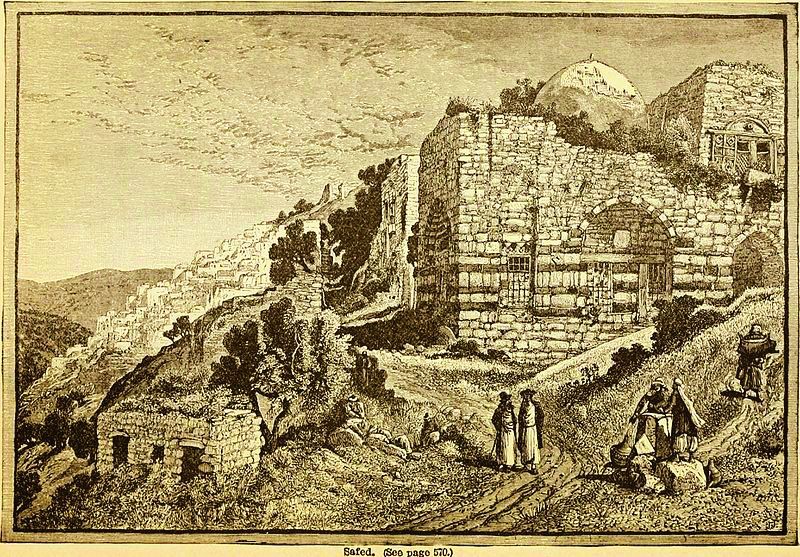

The messianic cabal surrounding Rabbi Yosef Karo shifted from Salonika to Safed. Engraving of Safed from 1888

The messianic cabal surrounding Rabbi Yosef Karo shifted from Salonika to Safed. Engraving of Safed from 1888*

Further reading

Mor Altshuler, “Prophecy and Maggidism in the Life and Writings of Rabbi Joseph Karo,” Frankfurter Judaistische Beiträge 33 (2006), pp. 81–110

Haviva Pedaya, “Crisis and Repair, Trauma and Recovery,” in Jewish Mysticism and the Spiritual Life, eds. Lawrence Fine, Eitan Fishbane, and Or N. Rose (Woodstock, Vt., 2011), pp. 171–82

Bilha Rubinstein, “A Terrible Fable and Enchanting Fiction: The Story of Joseph De-La Reina and Its Reflections in Two Novels of Yehoshua Bar Yosef,” in With Both Feet on the Clouds: Fantasy and Israeli Culture, eds. Danielle Gurevitch, Elana Gomel, and Rani Graff (Academic Studies Press, 2012), pp. 248–262.