Internal Eruption

Surprisingly, prior to October 1894, even Theodor Herzl didn’t think a Jewish state was possible. On October 17, reviewing a play for his longtime employer, Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse daily, Herzl slammed the production for its unrealistic premise of a Jewish return from exile. In the illustrious drama critic’s eyes, the Jewish character in Alexandre Dumas the younger’s La Femme de Claude (1873) was beyond belief:

The good Jew Daniel wants to find the old tribal home and lead his brethren back to it. But a man like Daniel would know that the Jews have nothing to do anymore with the historic homeland. It would be childish to go looking for its geographic location; any schoolboy knows where to find it. But if the Jews were ever really to “return,” they would discover the very next morning that they had long ago ceased to be one people. For centuries they have been rooted in diverse nationalities, different from one another, their similarities maintained only as a result of outside pressure. All oppressed people have Jewish characteristics, and when the pressure lifts, they behave like free men. (quoted in Ernst Pawel, The Labyrinth of Exile, p. 198)

A mere month later, after penning The New Ghetto in just seventeen days (October 21–November 8, 1894), an astounded Herzl reflected in his journal:

I had thought that through this eruption of playwriting I had written myself free of the [Jewish] matter. On the contrary, I got more and more deeply involved with it. The thought grew stronger in me that I must do something for the Jews. For the first time, I went to the synagogue in the Rue de la Victoire and once again found the services festive and moving. Many things reminded me of my youth, and the Tabak Street temple at Pest. (Theodor Herzl, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, trans. Harry Zohn, vol. 1, p. 11)

Herzl was a week into The New Ghetto when news broke of Alfred Dreyfus’ arrest on October 29. Like everyone else, the playwright presumed Dreyfus guilty. The infamous trial began in December, when the play had been finished for over a month. In late April 1895, mere weeks after completing his second draft, Herzl sat down and almost manically dashed off The Jewish State. Herzl’s diaries scarcely mention the Dreyfus trial and subsequent campaign, which took off only when new evidence of the defendant’s innocence emerged in 1896, well after publication of The Jewish State.

So it seems to have been The New Ghetto, not the Dreyfus Affair, that transformed Theodor Herzl. Both historian Jacques Kornberg and author Georges Yitzhak Weisz have suggested as much. But how did that change come about?

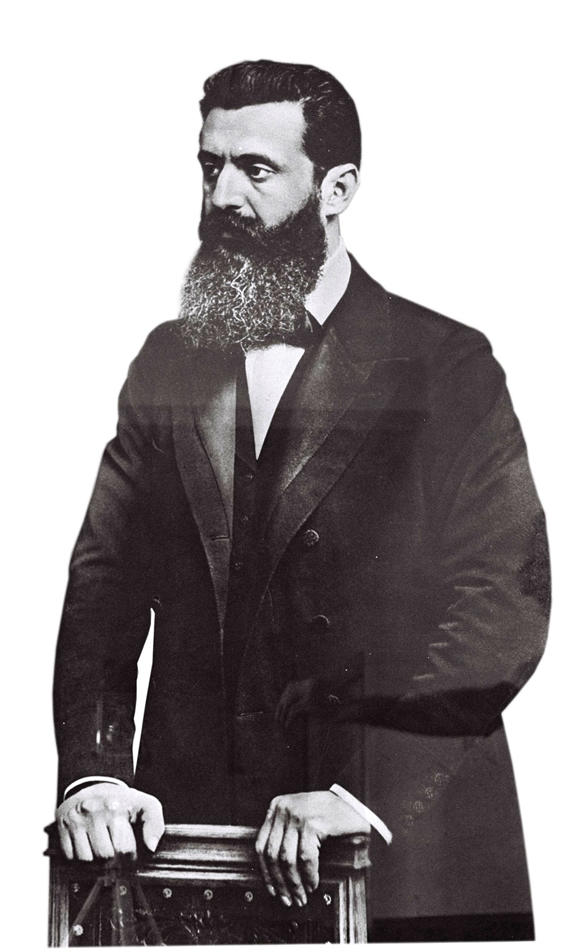

Dueling to the Death

Few know that aside from being a Zionist visionary, Theodor Herzl was a recognized playwright, whose works – usually fairly light and amusing – were performed in Vienna’s greatest theaters. From ages twenty to thirty-five, Herzl wrote almost one play a year; His Majesty (1886), The Poachers (1889), and What Will People Say? (1890), to name a few. But after the failure of The Lady in Black (1890), he lost confidence. His first child, Pauline, was born at this time, and shortly afterward, his close friend Heinrich Kana committed suicide.

Overwhelmed by the changes and crises in his life, Herzl abandoned the stage and accepted an offer from the Neue Freie Presse to serve as its Paris correspondent. Seeking new direction, he found it in covering a financial scandal then electrifying the French capital and involving the Panama Canal Company.

This French project, pioneered by Ferdinand de Lesseps on the heels of the celebrated Suez Canal, was financed by stock options. But the canal works went way over budget, resulting in the company’s 1889 bankruptcy and heavy losses to most investors. Until then, middlemen bribed a slew of politicians to keep the project afloat with further bond issues. Many Jews were party to the corruption, including one Jacques de Reinach, who gave newspaperman Édouard Drumont a list of the politicians implicated – and then committed suicide.

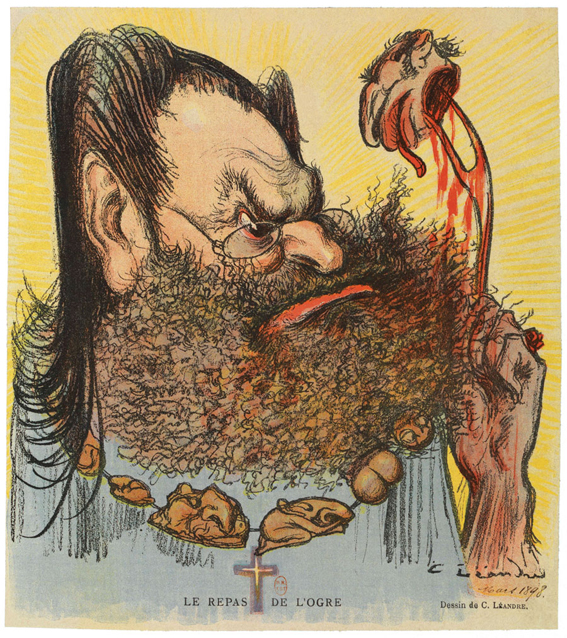

Drumont had authored the virulently anti-Semitic La France Juive, published in 1886 to great acclaim. Riding on his success, he founded La Libre Parole (Free Speech), an obscure daily that became famous overnight thanks to its revelations regarding the wheeling and dealing surrounding the Panama Canal.

Despite a months-long prison sentence intended to silence him, Drumont continued naming names, prolonging the agony by publishing a new one every day. La Libre Parole’s sales soared – an achievement Drumont repeated with his paper’s scathing coverage of the Dreyfus Affair two years later.

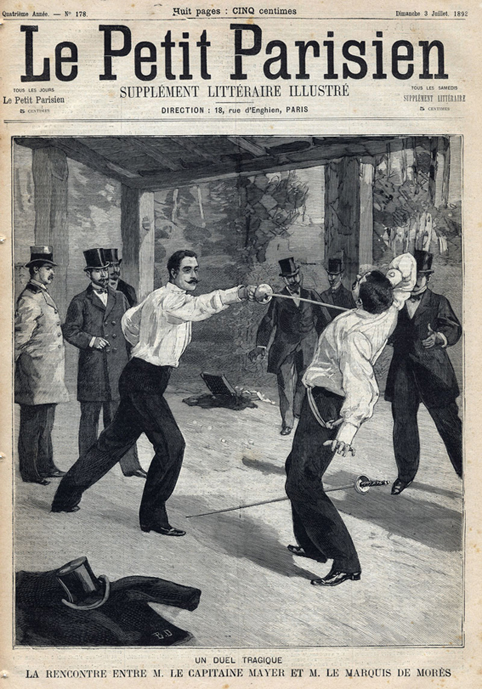

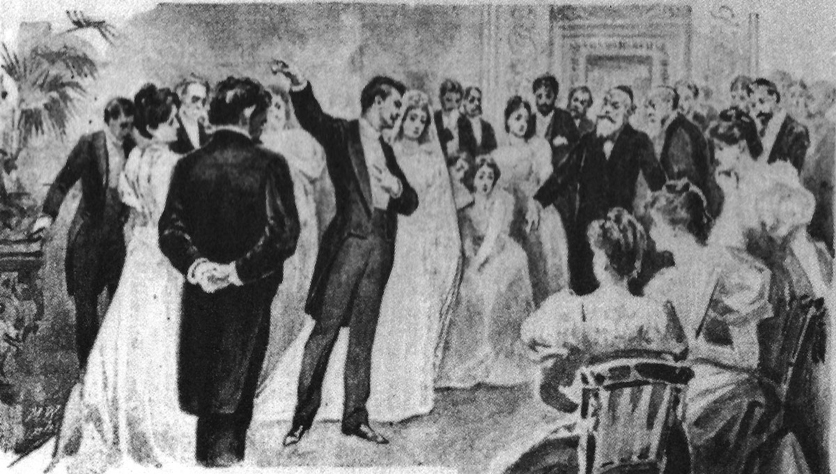

Accurately or not, the Dreyfus Affair has long been understood as catalyzing Herzl’s Zionism. Le Petit Parisien illustration of Dreyfus being formally stripped of his military rank

The Paris air crackled with anti-Semitism. On May 25, 1892, editors of La Libre Parole and the Marquis de Morès, founder of the Anti-Semitic League of France, crashed Juliette de Rothschild’s wedding at the Synagogue de la Victoire. They insulted the guests, threw acid on women’s dresses, and distributed anti-Jewish pamphlets while screaming, “Death to the Jews!”

Days later, La Libre Parole called for the exclusion of Jews from the French army. Indignant protests followed, to which Drumont coolly responded: “Let the Jewish officers offended by our articles designate a number of delegates, and we will oppose them with an equal number of French swords” (quoted in “Mayer, the Forgotten Dreyfus,” Le Nouvel Observateur, July 1993).

Indeed, many partisans of Drumont, often aristocrats, provoked Jews into duels, forcing them to risk their lives against all odds.

In one such confrontation, the Marquis de Morès, a quasi-professional swordsman, engaged Armand Mayer, a young Jewish captain in the French army’s Engineering Corps and an engineering instructor at the prestigious École Polytechnique. Mayer sustained a fatal chest wound. His funeral on June 26 attracted unprecedented crowds, incensed by the officer’s pointless death. Two years afterward, Herzl used the incident as the basis of The New Ghetto.

Trapped by Fate

Herzl’s play begins with a reception in honor of newlyweds Hermine Hellman and Jacob Samuel, attended by a host of Jewish stereotypes. Guests include Hermine’s ex, eastern European Emmanuel Wasserstein, with his accented German, whose losses on the stock exchange had disqualified him as a bridegroom; Jacob’s non-Jewish friend and confidant, Franz Wurzlechner; and a Hellman family associate, Count Von Schramm. The action involves the complex flotation of a mining company, loans, and financial problems.

Jacob explains to Franz that the count once challenged him to a duel, which he sensibly, if shamefully declined, apologizing instead. The admission drives a wedge between the young Jew and his friend, and they part – Franz to join an anti-Semitic political party, Jacob (who has been flirting with socialism) to advocate for exploited mine workers.

The miners strike, and the mine floods, killing workers and ruining investors – including Count Von Schramm. Goaded by the count one time too many, Jacob slaps his adversary and must then agree to a duel.

Death or dishonor? Herzl eventually realized that challenging Jews to a duel was just another way of killing them. The duel between the Marquis de Morès and Captain Armand Mayer, sketch from Le Petit Parisien, 1892

In the final act, a mortally wounded Jacob begs to escape Jewish society’s corrupt moral “ghetto.” As he expires, he warns his coreligionists, “Jews, my brothers, they won’t let you live unless you learn to die!” (The New Ghetto, first draft, quoted in Pawel, p. 203)

One of Herzl’s diaries describes the inspiration for The New Ghetto as a conversation he had with a sculptor named Samuel Friedrich Beer, who was working on his bust:

Our conversation resulted in the insight that it does a Jew no good to become an artist and free himself from the taint of money. The curse still clings. We cannot get out of the Ghetto. I became quite heated as I talked, and when I left, my excitement still glowed in me. […] I believe I hadn’t gone from the Rue Descombes to the Place Péreire when the whole thing was already finished in my mind. The next day I set to work. Three blessed weeks of ardor and labor. (Herzl, Diaries, p. 11)

After completing the play’s first version on November 8, 1894, Herzl discussed it with his close friend and fellow author Arthur Schnitzler, requesting that he present the work to Viennese or German theaters under an assumed name. Schnitzler found The New Ghetto shocking, especially Jacob’s closing line, “[…] they won’t let you live unless you learn to die.” After centuries of persecution, Schnitzler thought, Jews had nothing more to learn about death. He asked Herzl to delete the words “unless you learn to die” and add at least one sympathetic Jewish character. The playwright responded that he’d yet to meet any in Vienna (Jacques Kornberg, Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism, p. 154). After Herzl’s passing, Schnitzler had a character in one of his novels say:

I myself have only succeeded up to the present in making the acquaintance of one genuine anti-Semite. I’m afraid I am bound to admit […] that it was a well-known Zionist leader. (Arthur Schnitzler, The Road to the Open [London: Howard Latimer Ltd., 1913], p. 69)

Herzl’s Invisible Ghetto

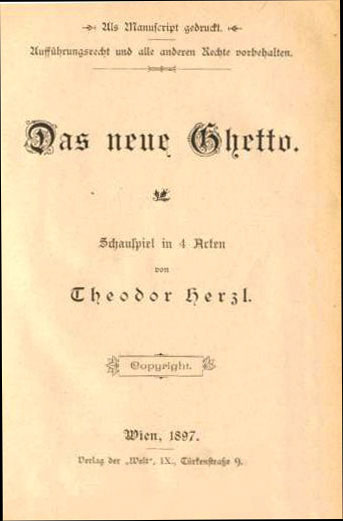

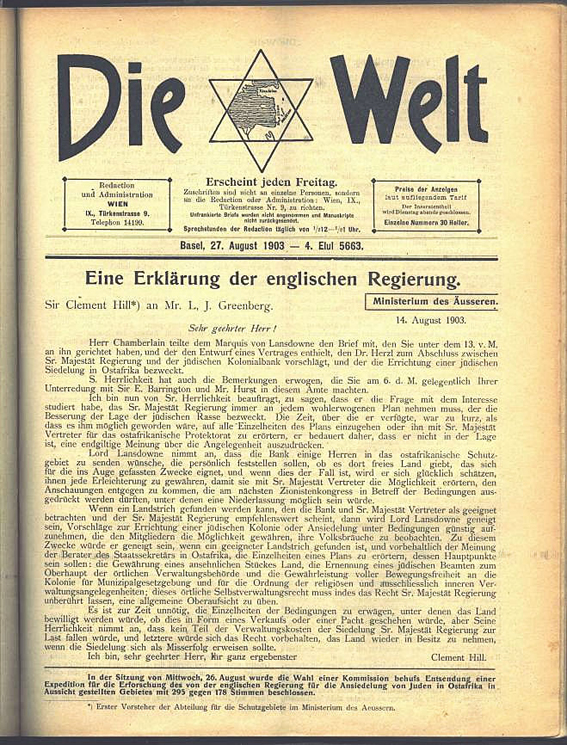

The New Ghetto was serialized in 1898 in Die Welt, Herzl’s Zionist weekly. The play was performed at Vienna’s Karl Theater from January 5 to February 15, 1898, with further runs that year in Berlin and Prague. Strangely, it was never produced again.

The fact is, the work is disconcerting.

Given Herzl’s great popularity as a journalist and leader of the controversial new Zionist movement, The New Ghetto was widely reviewed. But nobody knew what to say. Initially rejected by the Austrian censors, the play was eventually approved because it echoed the prevalent anti-Semitism, presenting Jews in a terrible light. An early attempt to translate the work into Hebrew foundered for this very reason.

So is The New Ghetto flawed? Anti-Semitic? The pace is lively, the characters endearingly human. The historical value of the text is obvious: no mere jaunt through the Habsburg capital at its height, but a considered portrait of the social-urban conflicts of 19th-century Europe: aristocrats in decline, Jews on the rise, and the tensions of anti-Semitism and assimilation. Above all, however, the play plunges deep into the heart of Herzl himself.

The New Ghetto shows that even if the old ghetto had disappeared, Jews were confined to a stifling moral one. Leaving it was imperative, yet this ghetto served an essential role: it provided the imaginative space in which Herzl, the assimilated Jew, could become a proud member of his own race.

Herzl clearly projected himself into the moral clash between Jew and aristocrat in The New Ghetto. This conflict dominated his own life. Just as Jacob Samuel is a lawyer without a clientele (like Friedrich Loewenberg, an unemployed attorney in Herzl’s later Zionist novel, Altneuland), the author himself was socially a “man without a country.”

Having absorbed aristocratic values in high school and university, genteel, assimilated Jews like Herzl struggled with Viennese society in the late 19th century. Non-Jews rebuffed them less and less politely; the elder generation of Jewish businessmen, who’d succeeded precisely because they weren’t yet fettered by romantic European chivalry, disgusted them.

Herzl’s generation was repulsed by the mercenary Jewish bourgeoisie. Jacob Samuel’s wedding reception, the opening scene of The New Ghetto

Their selflessness was rooted in love of art, a profound sense of honor, and an almost reckless contempt for materialism, money, and death. Herzl’s close friend Heinrich Kana, whose suicide shook him terribly, was an almost inevitable casualty of the impossibility of sustaining such values. These young Jews worshipped at the altars of altruism and generosity, determined to help the weak and oppressed.

Steeped in this refined morality, as personified by The New Ghetto’s hero, Jacob Samuel, Herzl could only despise Jewish tycoons like his father-in-law, the rich industrialist Naschauer, and the Hirsch and Rothshild bankers he met in Paris and castigated in his journal. In a subtle irony, Herzl aristocratically “squandered” his father-in-law’s fortune on the Zionist dream. He admired those of noble birth, but they loathed him as a Jew. They too were hypocritically enmeshed in the pursuit of the wealth that their elegant lifestyle demanded.

The Morès-Mayer duel, at the heart of Herzl’s play, probably also stirred a memory still smoldering inside him. As a journalist in Vienna, he’d been drawn into a ridiculous argument in a café, almost embroiling him in a duel from which he escaped – like Jacob Samuel – only by apologizing.

Indeed, The New Ghetto has a Freudian quality that reflects and even anticipates the events of the playwright’s life. Jacob’s wife, Hermine, is clearly based on Herzl’s long-suffering spouse, Julie Naschauer, heiress to untold millions, the child-woman foreign to her husband’s secret concerns. Herzl was extremely attached to his mother, Jeanette, who survived him by over seven years. The play’s moving portrayal of his protagonist’s despairing mother mourning the untimely death of her only son is thus almost shockingly prophetic.

Most of all, the work captures Herzl’s internal paradox: his aristocratic values made him a proud Jew yet cut him off from his own people; and he sacrificed for others but not to save himself.

The World of Psychodrama

The New Ghetto shows Viennese Jewry caught between the decline of the gentry and the rise of the proletariat. The nobles are victims of their own values. Their fortunes waning, these aristocrats survive by either marrying money or manipulating the stock market. Faced with these puppets – their stupidity often equaled only by their brutality – is a suffering proletariat, represented in the play by the dignified miner, Peter Vednik. Despised by both classes, the Jewish nouveaux riches depend on the stock exchange and its acrobatics – which Herzl’s plot explains at length.

Anti-Semitism took the assimilated Jews of Vienna by surprise. A few months after Herzl completed The New Ghetto, Karl Lueger was elected mayor of Vienna on an openly anti-Semitic platform. He took office in 1897, the year of the first Zionist Congress in Basel.

For Herzl, the very writing of the play was a psychodramatic process.

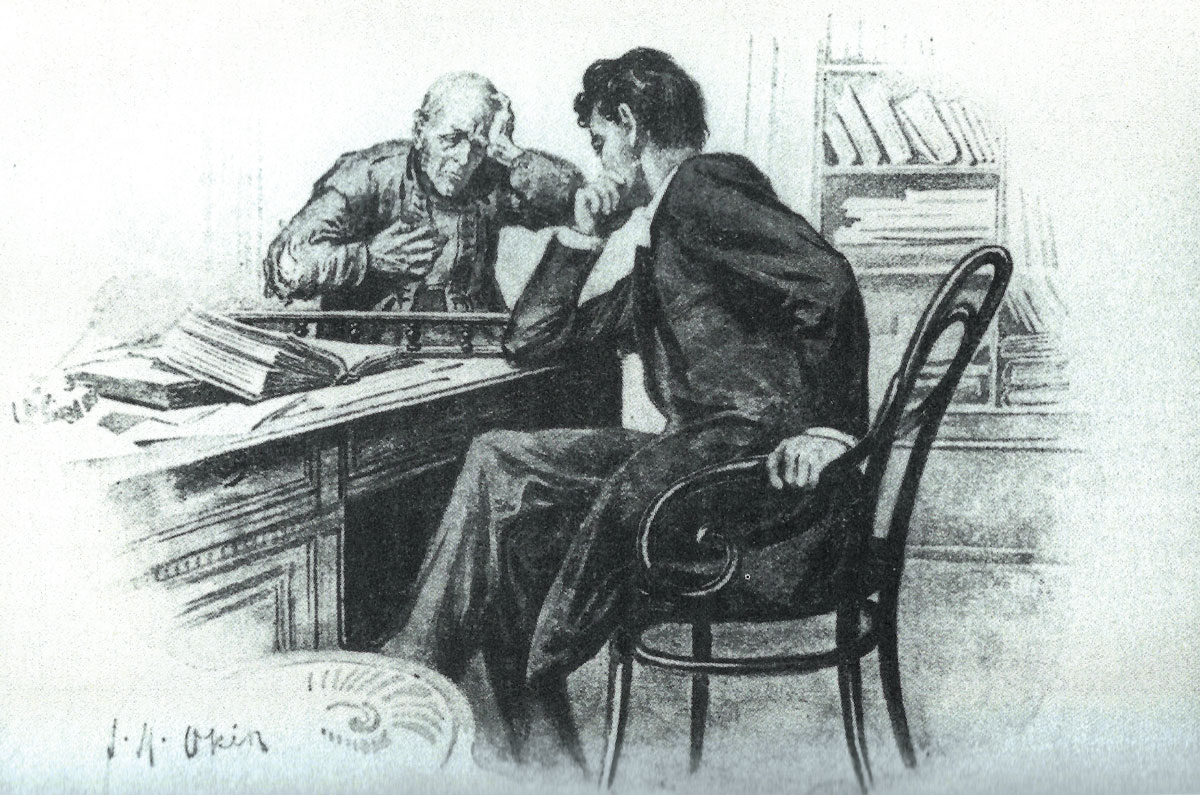

Attempting to assist the exploited working classes in their struggle against their rich employers, Jacob Samuel meets with miner Peter Vednik in his legal office. Illustration by Joseph Michael Okin, 1898

Whereas Freudian psychology says, “Tell me what happened,” Jacob Moreno’s psychodrama (founded, like Zionism and psychoanalysis, in Vienna) says, “Show me what happened.” First a trauma is reenacted, with the protagonist casting his acquaintances as the main characters. This exercise leads to the unearthing of an episode buried deep in his psyche. The protagonist must then connect the two scenes. A recent argument with a friend, for example, might open up an unresolved conflict with one’s father. The association between the two incidents creates the possibility of resolving the earlier conflict.

When writing The New Ghetto, Herzl projected himself entirely onto Jacob Samuel, a perfect psychodramatic double. A well-to-do, assimilated Jew, Jacob attempts to live by the aristocratic notions inculcated in him by his non-Jewish education, but these very values destroy him. Choosing ideals over income, he cannot make ends meet. Throwing caution to the wind, he duels and is killed. His good intentions prove fatal: the miners’ strike he organizes results in death and destitution while harming the capitalists responsible – himself included.

By contrast, the real aristocrats in the play (such as the villainous Von Schramm) don’t bother with aristocratic values. Money matters most, and they’ll stop at nothing to get it. And Herzl-Jacob, the Jew, will always be rejected. Hence Jacob’s separation from Franz, his non-Jewish friend. Jacob will never be like them.

Above all, the play shows us Herzl’s metamorphosis. Just as the psychodramatic protagonist frees himself from trauma by reliving it, thereby realizing its relative insignificance, with the writing of The New Ghetto, Herzl relives his adoration of the German aristocracy and Western culture. He reenacts a recent event – the Morès-Mayer duel, in which a highly refined Jew is killed by a gangster aristocrat – to reveal his own position as an aristocratic Jew (or an “artist Jew,” as he called himself) in Viennese society. Herzl-Jacob realizes he has only himself to blame for his failure, his discomfort, his profound maladjustment. Through Count Von Schramm’s brutality, the author-protagonist recognizes his values as futile and self-destructive.

From Playwright to Prophet

In a gradual role reversal, Emmanuel Wasserstein, the “stock market Jew” with his ridiculous mannerisms and east European inflection, conceived at first as the drama’s only comic relief, becomes increasingly pivotal and positive. His vulgarity hides a more solid and effective generosity than Jacob Samuel’s.

Wasserstein is Jacob’s mirror image. Money is his main value, because he sees things as they are. Honor is irrelevant. He agrees to be treated like a rag. When Count Von Schramm threatens Jacob with a duel, Wasserstein is unmoved. He has nothing to fear – he’ll never fight, never prefer death to dishonor. His priorities lie elsewhere.

A simple man, Wasserstein can afford to be magnanimous to his enemy when the latter is facing ruin. His sympathy for the miners is sincere, as is his love for Hermine, whom he’ll undoubtedly marry as soon as she finishes mourning Jacob. Wasserstein’s success is complete; prepared to accept the humiliation that costs him only his pride, he gains wealth, happiness, and honor.

The entire play is a reversal of fortunes: the uncouth Ostjude Wasserstein becomes the hero, and Jacob the aristocratic Jew dies, killed by his own contradictions.

In writing The New Ghetto, Herzl exorcises his desire to assimilate into Viennese high culture, purging himself of his illusions, his fascination with Western culture. The apparently liberated Jew lives in a moral ghetto, Herzl realizes. Those who dare leave it do so at their peril. Through Wasserstein, he comes to appreciate his own Jewish identity.

Naturally, then, after completing the play, Herzl returns to the synagogue and ponders how to improve the Jewish condition. He understands that only a Jewish state, in which Jews live freely by their own standards, can deliver them from their destructive Western ethos and give their lives meaning. Having completed The New Ghetto, Herzl no longer yearns to be a famous playwright; he wants to build a state.

Seventy years after the founding of the State of Israel, Jacob Samuel’s puzzling last words – which Arthur Schnitzler found so painful – suddenly take on new meaning: “Jews, my brothers, they won’t let you live unless you learn to die!” Herzl’s dramatic turnaround, vindicating the authentic Jew Wasserstein over assimilated Jacob, laid the foundations for a new political creation – the Israeli, who has a homeland worth dying for. From the psychodrama of The New Ghetto sprout the politics of Zionism; the dry bones are clothed anew in skin and sinew. And thus Theodor Herzl, the playwright turned prophet, gave birth to The Jewish State.