Herzl’s Port

“The coast of Palestine rose on the horizon on a spring morning following one of the mild, soft nights common in the eastern Mediterranean. They stood together on the bridge of the yacht and stared steadily through their telescopes for ten whole minutes, looking always in the same direction.

“I could swear that that was the Bay of Acco over there,” remarked Friedrich.

“I could also swear to the contrary,” asserted Kingscourt. “I still have a picture of that Bay in my mind’s eye. It was empty and deserted twenty years ago. Still, that’s the Carmel on our right, and to our left is the town of Acco.”

“How changed it all is!” cried Friedrich. “There’s been a miracle here.”As they approached the harbor they made out the details with the help of their excellent lenses.

Great ships, such as were already known at the end of the 19th century, lay anchored in the roadstead between Acco and the foot of the Carmel. Behind this fleet they discerned the noble curve of the Bay. At its northern end, the gray fortress walls, heavy cupolas, and slender minarets of Acco were outlined in their beautiful ancient Oriental architecture against the morning skies. Nothing had changed much in that skyline. To the south, however, below the ancient, much-tried city of Haifa on the curve of the shore, splendid things had grown up. Thousands of white villas gleamed out of luxuriant green gardens. All the way from Acco to Mount Carmel stretched what seemed to be one great park. The mountain itself, also, was crowned with beautiful structures. Since they were approaching from the south, the promontory at first obscured their full view of the city and the harbor. When, at last, the landscape was revealed to them in its entirety, Kingscourt’s “Devils!” became legion.A magnificent city had been built beside the sapphire-blue Mediterranean. The magnificent stone dams showed the harbor for what it was: the safest and most convenient port in the eastern Mediterranean. Craft of every shape and size, flying the flags of all the nations, lay sheltered there.

Kingscourt and Friedrich were spellbound. Their twenty-year-old map showed no such port, and here it was, as if conjured up by magic. Evidently the world had not stood still in their absence.” (Theodor Herzl, Old-New Land, trans. Lotta Levensohn [New York: Bloch Publishing Co. and Herzl Press, 1941, pp. 37–8)

After a twenty-year absence, Kingscourt and Friedrich, the two heroes of Herzl’s utopian novel, revisit the Promised Land. They realize how much has changed when their ship approaches Haifa Bay – and its new port.

credit title test

credit title testThe ship Volcania docked in Haifa’s port, Winter 1933

Herzl published Altneuland (Old-New Land) in 1902. Though no urban planner, he realized that a modern port could make Haifa the economic engine driving the Jewish state. Twenty years later, in 1922, British engineer Sir Frederick Palmer confirmed Herzl’s intuition. Sent by the Mandate government to choose the most appropriate location for a modern deepwater port, he selected Haifa Bay.

Whose Port Is It Anyway?

Construction began in 1927. The many tons of sand extracted from the seabed to deepen the harbor near the shoreline were used as landfill, creating a strip of solid ground on which the port’s warehouses and machinery were built. Haifa Port became the gateway to the Promised Land, just as Herzl had projected. In the first years of the British Mandate, the port employed relatively few, mainly Arabs. Jaffa remained the primary port, until the government moved most shipping northward.

Pile driver preparing foundations in Haifa Port, July 1932, from British documentation of the port’s construction

Photo: Giora Ben Dov collection

The Zionist leadership understood that if the country’s ports were dominated by Arab labor, Jewish imports and exports could easily be cut off by nationally motivated industrial action. Immigration too was at the mercy of the port workers. For any kind of Jewish economy to be viable, Haifa Port had to be run by Jews. But by the end of the 1920s, the Zionist labor organizations had still made no headway in this direction.

In 1926, political activist Abba Hushi left his home in Kibbutz Beth Alpha to head the Haifa Workers’ Union. From that moment until his death in 1969, his vision of Haifa as a booming, port-based metropolis became synonymous with his uncompromising personality. Hushi was elected mayor in 1951, having already transformed the port. He established Haifa as a “red city,” where labor unions reigned supreme, creating a culture of workers’ rights and secular values that profoundly influenced the rest of the country.

Union leader turned mayor of Haifa. Abba Hushi, painted by Yavniel, oil on canvas

Hushi’s efforts to introduce Jewish labor at the port while it was still under construction were a dismal failure. He recruited kibbutz members waiting in Haifa until they could set up new settlements, but these workers balked at the heavy lifting, especially as stop-gap employment. Seeking a creative solution, Hushi found one in Thessaloniki (Salonica).

Greco-Jewish Docks

On September 22, 1931, the Haaretz daily ran an article titled “Jewish Immigrants from Thessaloniki – Bother or Blessing?” The author, Thessaloniki native Barukh Uziel, had arrived in Palestine in 1914 and been working with immigrants from his hometown for over a decade. He suggested that Jewish dockworkers from Greece could solve Haifa’s labor problems.

Member of parliament Barukh Uziel (second from right) at the opening of Israel’s sixth Knesset. Photo: Moshe Pridan, Israel Government Press Office

Jewish exiles from Spain and Portugal had first settled in Thessaloniki after the Ottoman conquest in the 16th century, their capabilities and culture creating a vibrant and fairly autonomous community. The bustling port of Thessaloniki was famous for its Jewish dockworkers; unable to function without them, it closed on Saturdays as well as Jewish holidays.

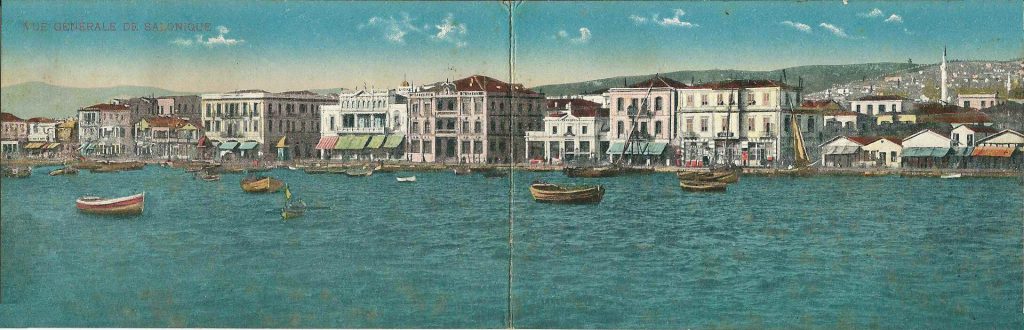

One of Greece’s largest ports, Thessaloniki has served as a gateway to the Balkans for centuries. Thessaloniki’s harbor, circa August 1917

This golden age ended in 1912, when Greece defeated Turkey in the Balkan Wars preceding World War I. During the next two tumultuous decades, the community’s position deteriorated rapidly. Population exchanges between the two squabbling countries flooded Thessaloniki with thousands of Greek nationals, upsetting the delicate balance between Jews and other locals. Many of the newcomers were fisherman, competing directly with the Jews, who also lived off the sea.

Then a terrible fire broke out in 1917, destroying most of the Jewish area. Rebuilding was both expensive and complicated by ethnic tensions. New legislation compounded the Jewish community’s difficulties. First and foremost, Sunday became the official day of rest, forcing Jews to choose between Sabbath observance and their jobs. Needless to say, the port no longer closed on Saturdays.

The Great Depression of 1929 intensified Greek nationalism, and Jews were blamed for the republic’s economic woes. During the 1931 Camp Campbell pogrom, two thousand rioters ravaged this Jewish neighborhood for four days, leaving five hundred families homeless and one Jew dead.

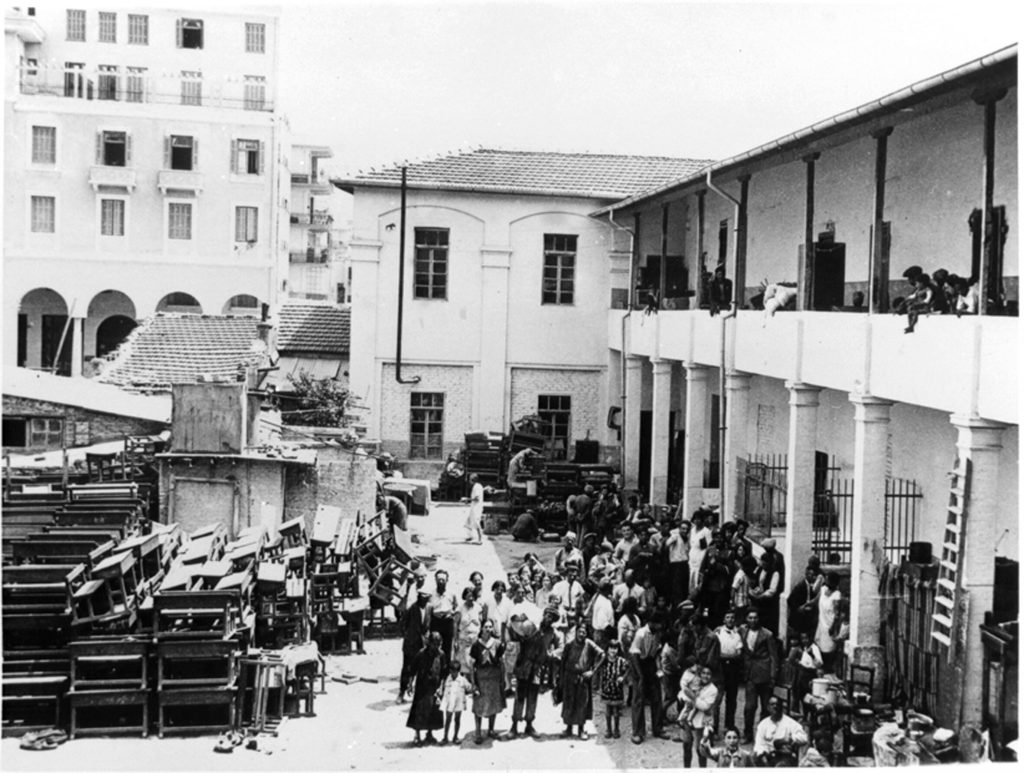

Fearing further attack, Jews leave their homes in Thessaloniki’s Campbell Camp district after the infamous pogrom of July 1931

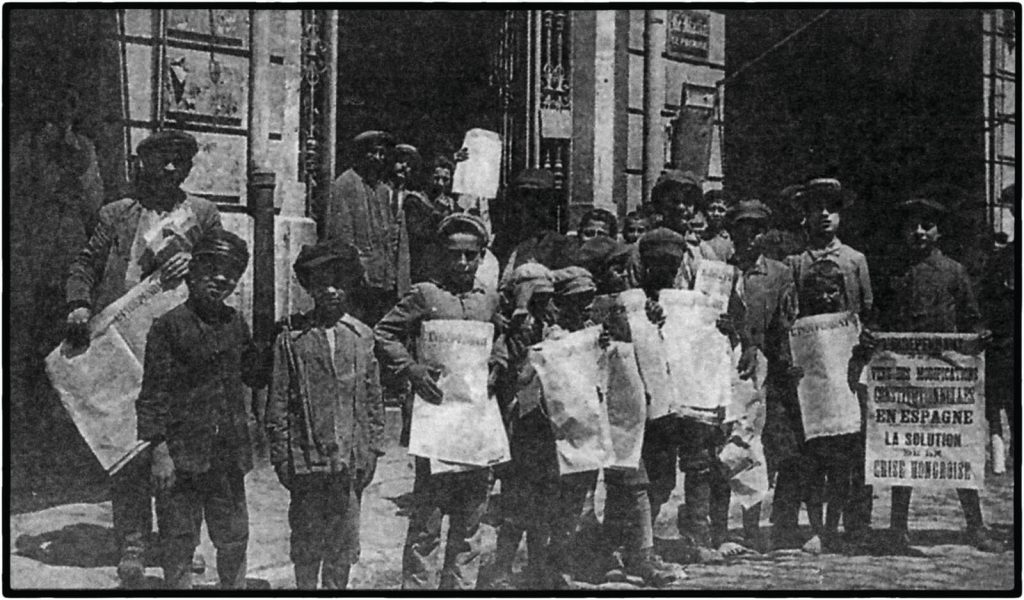

Jewish children in Thessaloniki selling Jewish newspapers, early 20th century

Uziel’s article appeared late that summer, after Yom Kippur:

We must entrench ourselves in every field of economic endeavor in the land of Israel, and the conquest of the sea is vital for several reasons. No Jews are as capable when it comes to seagoing professions, and none could occupy these positions as swiftly, easily, and naturally – and inexpensively – as the Jews of Thessaloniki. (Shai Srougo, From the Port of Thessaloniki to Haifa Port – Immigration of Dockworkers from Thessaloniki to Palestine between the Two World Wars [master’s thesis, University of Haifa, 2003], p. 88 [Hebrew])

The article was clearly a Zionist’s honorable solution to his home community᾽s problems. At first neither that community nor the Zionist leadership picked up the gauntlet Barukh Uziel had thrown down. Jews had begun leaving Thessaloniki but not for Palestine, and in nothing like the numbers Uziel had envisaged.

A year and a half later, feeling that time was running out, Uziel set up a “Maritime Council” to bring as many dockers as possible from Thessaloniki. The council included members of the Committee for Haifa and leaders of the Thessalonikan Jewish community in Palestine, but Uziel realized he needed Abba Hushi in order to get anywhere. He knew Hushi was desperate for Jewish manpower at Haifa Port. Furthermore, though the Mandate government’s White Papers of 1922 and 1930 had limited Jewish immigration to a trickle of Jews from fascist regimes, Labor Party member Hushi could surely obtain permits for the Jews of Thessaloniki.

Socialist Fantasy

Hushi joined the Maritime Council and set about bringing aboard Moshe Sharett of the Jewish Agency. Sharett (later Israel’s second prime minister) promised as many immigration certificates as needed – just in time, as work on the port was proceeding apace and its dedication was fast approaching.

The council let the Greek members of the World Zionist Organization decide which families to bring from Thessaloniki, and the first fifteen landed in Haifa in the summer of 1933. Ironically, these traditional Jews began work on a fast day – the Ninth of Av. The excitement of their arrival soon turned to dismay, as the supposedly professional port workers sank under their loads. The WZO representatives in Thessaloniki, it turned out, had used the certificates to send friends and relatives to safety rather than the long-awaited stevedores.

Barukh Uziel and fellow Thessalonikan Maurice Rafael had a hard time persuading Abba Hushi that the laborers he’d received weren’t the legendary Jewish dockworkers. Eventually he agreed to journey to Greece himself in order to see the “Jewish port” in action and choose the next batch of immigrants himself.

Sailing into Thessaloniki less than a month after the workers’ arrival in Palestine, Hushi was amazed by what he saw. Brawny, seasoned, and hardworking, these Jewish laborers were right out of a socialist Jewish fantasy. Astonished, he wrote:

“The Jews here spend their lives doing things even the Arabs can’t do back home. I stood on the docks and watched the ships being unloaded just as you’d told me. I spoke to the workers carrying the coal, and they were as blackened by it as the Egyptians from Port Said who work in Haifa. But the Thessalonikans are better workers”. (Isaac Molho, Thessalonikan Mariners in Israel – Vision and Fulfillment, p. 58 [Hebrew])

In Jaffa Port, as opposed to Haifa and Tel Aviv, almost all the workers were Arabs, and the dockers from Thessaloniki played a very minor role. Jewish and Arab laborers unloading cargo

in Jaffa, 1949

Photo: Zoltan Kluger, Israel Government Press Office

Dockers at work in Tel Aviv’s port, 1948

Photo: Israel Government Press Office

Tel Aviv’s port remained extremely active until Ashdod opened its own facility in 1965. Tel Aviv Port, September 1936

Courtesy of Giora Ben Dov

After ten days in the port city, Hushi chose one hundred workers, requiring each to sign a demanding contract in Hebrew and Ladino:

“Hours: between ten and fifteen a day, subject to demand and the foremen’s requirements, from 6 am to 10:30 or 11 pm, with a short break in the morning and a lunch hour.

Day off: days off are not limited to a specific day of the week and will be allocated depending on work requirements. Should urgent conditions force me to work on the Sabbath, I will have no grounds for complaint.

Work conditions: loads will average 100–120 kilograms, to be carried distances of two hundred meters. However, I am prepared to carry up to 250 kilos over distances of thirty to seventy-five meters”. (ibid., p. 59)

Another clause, aimed against the rival Revisionist unions, stated:

“On arrival in Palestine, I hereby undertake to join the General Hebrew Workers’ Union in the land of Israel”. (ibid.)

Facing a growing economic burden and increasing anti-Semitism, the Thessalonikan Jews took this draconian contract in stride. Abba Hushi’s well-publicized visit made thousands more consider Palestine an option. Another two hundred families soon arrived in the Holy Land, and many more lamented the shortage of immigration certificates.

The Thessaloniki dockworkers showed their mettle in Haifa; even Arab contractors preferred them. Theirs was a unique achievement – Jewish labor remained a distant dream in all other public works in the country. But no Jewish laborers in any other field matched the Thessalonikans’ skill and experience.

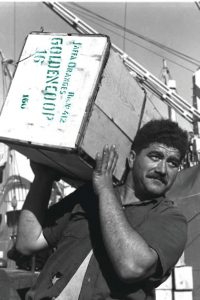

The professionalism of the Jewish dockworkers from Thessaloniki, nurtured over generations in the ancient, major Greek port, instantly made them the most skilled and sought-after laborers in Haifa Bay. Carting oranges on deck in Haifa, 1948

Photo: Hugo Mendelson, Israel Government

Press Office

Other families from Thessaloniki whose livelihood was connected to the port emigrated to Palestine as well. A few shippers settled in Haifa, initially partnering with Arab colleagues to win contracts. Storage professionals brought their expertise to the port; porters and maritime engineers followed.

The dockworkers’ reception in Palestine wasn’t the smoothest – their contract promised trouble. Though the religious Mizrahi party raised a stink, the clause refusing to guarantee Saturday as a day of rest was put into practice, and dockworkers who’d never lifted a finger on the Sabbath in Thessaloniki found themselves slaving away on Saturday in the Holy Land.

When the Arab Revolt of 1936 closed down the port in Jaffa, the Jewish workers’ unions were authorized by the Mandate government to establish their own port on the shores of Tel Aviv. Once again, most of the burden fell on the workers from Thessaloniki. Hustled south to Tel Aviv from Haifa, they set up the new port’s jetty in one night (though twenty-four hours later, repairs were already needed). At this port, their native Ladino was the language of choice.

Exploited But Safe

Historian Shai Srougo questions the idyllic emigration and absorption recollected by Thessalonikan expats. Isaac Molho’s and Barukh Uziel’s dewy-eyed memoirs assume the purest motives on everyone’s part, but Srougo sees ominous parallels between the tale of the Thessalonikan dockworkers and Arthur Ruppin’s “import” of Yemenite Jewish artisans and farmers in the early 20th century. Ruppin’s scheme was a fall-back option after Jewish villages refused to employ young Jewish pioneers instead of cheap, experienced Arab labor. He and other Zionist leaders hoped the Yemenites would provide a less expensive Jewish alternative. Srougo identifies similar colonialism in the way the Thessalonikans were brought to Zion to perform backbreaking tasks under harsh conditions. Both stories, consciously or otherwise, reflect the hubris and prejudice of eastern and central European Jews regarding other Jewish communities.

So why do the Thessalonikans paint such a rosy picture? Srougo notes that Hushi’s plan saved hundreds of families from certain death along with the rest of the Jews of Thessaloniki when the Nazis conquered Greece. Furthermore, the Thessalonikan community has integrated and prospered in Israel.

While Srougo’s points are valid, his imperialist-colonialist narrative is oversimplified. Abba Hushi and co. may have taken advantage of Thessalonikan Jewry’s distress, but they were motivated by Jewish solidarity and a Zionist vision of Jewish ports run by Jewish workers. Some of that feeling comes across in the letter Hushi sent to his council after a few days in Thessaloniki:

“… I’m more enthusiastic than ever about our task, and I’ll devote my best efforts to its accomplishment. Until now, I’ll admit, I was interested in only one thing – winning the labor battle in Haifa. Now I have a new goal, no less important: to save hundreds – and in the near future, more than hundreds – of good, productive Jews from crisis, hunger, and oppression, and to bring them from slavery to freedom, from exile to their homeland”. (ibid., pp. 57–8)