Two Takes, One Woman

Scene 1: a lavish European ballroom complete with crystal chandeliers, plush Persian rugs, and exquisite porcelain vases. Flowers, champagne flutes on silver salvers, exotic hors d׳oeuvres served by black-clad waiters – all in honor of the hostess׳ birthday.

Background music: a Viennese waltz, the musicians seated off to the side.

The belle of the ball mingles effortlessly with her elegant guests, her wavy brown hair cascading carelessly over her bare shoulders. A deep red evening gown sparkling with sequins sets off her perfect figure; a double string of pearls adorns her long, graceful neck. Her green eyes flash habitually at each witty comment, and her veiled gaze lends her every move an air of sensual mystery. She flirts with the evening׳s guest of honor – the führer – and they clink glasses of rich-toned merlot.

Hitler offers a toast – to his beautiful hostess; to the munitions deal he׳s signed and its significance for German rearmament; and to Austria, which will soon rid itself of Jews forever. Little does he know that the birthday belle is one of them. And no one dreams that in a few short years, on the very day she celebrates her twenty-fourth birthday, Germany will be shattered by Kristallnacht. Cut.

Scene 2: the dining room of a Hollywood villa. Cigarette smoke, a table strewn with the untidy remains of a hasty supper. A few couples sit around, yawning. Lazy conversation.

Background music: the mechanical notes of a player piano.

A bohemian-looking man of about forty huddles with a younger woman in an airy summer dress. In the newspaper on the coffee table, a headline announces the ravages of the German blitz in Europe. The woman׳s wavy brown hair tumbles at her shoulders just as before, but her glance is piercing now, her eyes hard and glinting. She and her companion discuss how hard it is for the Allies׳ long-distance guided torpedoes to sink German U-boats and other ships when their guiding signals are constantly jammed by German radio interference. He smiles suddenly as her idea penetrates, then pulls paper and pen from his jacket pocket and begins to sketch. She smiles and flutters her eyelids.

Who could imagine this exchange would lead to some of the most advanced communication technologies in the world?

Hedy Lamarr in The Conspirators (1944)

Skin-Deep

In Hollywood Lamarr was something of an oddity. She didn׳t drink, didn׳t dance, and sketched at a drafting table between takes. Her father had enjoyed explaining to Hedy the engineering marvels of the early 20th century – from automobiles to trams to planes – and her natural grasp of technicalities had perhaps partly attracted Mandl׳s attention. Escorting him to interminable meetings, she׳d absorbed the details of depth charges detonated by radio signals. In 1940, with German subs sinking one Allied ship after another – including one carrying ninety child refugees – she recalled those conversations. Torpedoes could be remote-controlled by radio waves, but the targeted submarine could lock in on the frequency of the launching signal and jam it, sending the missile off course to detonate harmlessly miles away. The Allies had to find a way to turn the tables…

At one of the intimate social evenings she attended soon after divorcing her second husband, Lamarr was introduced to fellow German speaker George Antheil, an avant־garde American composer with a scientific bent. He׳d made waves in Paris with his 1924 Ballet Mécanique, incorporating the cacophony of war – bells, sirens, propellers, and gongs – as well as sixteen player pianos (synchronization problems ultimately forced all but one to be replaced with pianists). His only brother had perished in a plane explosion that summer in Finland, and Antheil was eager to help the war effort.

The bad boy of Paris. Antheil composing in the 1940s. Courtesy of the George Antheil Estate

To overpower the Nazis at sea, Lamarr came up with the idea of frequency hopping. She envisaged a missile guided by a plane flying overhead; if the signal was constantly changing frequency, it couldn׳t be blocked. But how to make the guiding mechanism and the torpedo ״hop״ to the same frequencies simultaneously? Enter Antheil and his synchronized pianos.

Small rolls of paper perforated with holes and slots, corresponding with musical notes, were loaded onto spools inside the player pianos. This ״sheet music״ determined which of the instrument׳s eighty-eight keys were depressed, and as long as the rolls were identical and spooled at the same speed, theoretically any number of pianos could play in synchronization. Lamarr realized that the same mechanism could keep a missile guidance system in sync with a torpedo, even as the transmitter and receiver both jumped from one radio frequency to another (among eighty-eight in all). The problem was how to make (1) rolls small enough to fit inside the torpedo, and (2) paper that wouldn׳t tear.

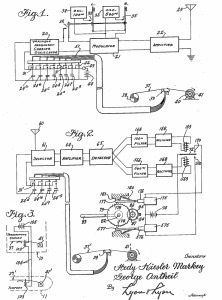

Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil worked together on the project, with Hedy employing engineering professor Samuel Stuart Mackeown for a year to turn the concept into hard science. They patented their ״secret communications system״ in August 1942. Unfortunately, it had few fans. The U.S. Navy dismissed ״Hedy׳s folly,״ claiming the paper roll mechanism would weigh down the torpedoes. Antheil later mused that he and Lamarr shouldn׳t have referred to synchronized music in their terminology: ״My God! I can see [them] saying, ׳We can׳t put a player piano in a torpedo!’ ״ (Richard Rhodes, Hedy׳s Folly, p. 187).

Diagrams from the original patent application for Lamarr and George Antheli’s invention, 1942

Lamarr made further efforts to do her part for the war. She volunteered in the Hollywood Canteen, where stars served local enlisted men waiting for their active duty to begin. Hedy couldn׳t cook, but she washed dishes and boosted morale by dancing with soldiers. She tried joining the National Inventors׳ Council to help screen other potentially useful patents, but council member Charles Kettering chauvinistically quipped that she׳d achieve more by using her pretty face to peddle war bonds – which she did, with great success.

Though Antheil and Lamarr׳s invention wasn׳t used in World War II, it came into its own during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 (three years after the composer׳s death), with transistor technology replacing a bulky clockwork mechanism. The navy used frequency hopping to secure military communications from enemy interception rather than to guide missiles. In any case, the patent had expired by then, and Lamarr had no interest in fighting for recognition.

Courtesy of the U.S. Navy

Courtesy of the U.S. NavyKeeping torpedoes on target challenged both the Axis and the Allies in the struggle to rule the seas. Torpedo fired from the USS Dunlup in World War II

Fizzling Out

dabbling in innovations sublime to ridiculous (such as a tissue box cover with a pocket, and cubes that dissolved into a fizzy drink resembling Coca-Cola in color but Alka־Seltzer in taste).

Spread-spectrum technology – the basis of frequency hopping – really took hold in the 1980s, when a bandwidth shortage interfered with radio and television broadcasting. It׳s a bit of a stretch to credit Hedy Lamarr with everything from mobile phones to Bluetooth and GPS, but all take advantage of signal division and reconstruction over a range of channels. Multiple users, privacy protection, and interference prevention on a single band all owe something to her, although it was probably mostly a publicity stunt when she received the Electronic Frontier Foundation Award in 1998, at age eighty-three. More private than ever, she accepted the honor by phone.

Though Hedy Kiesler Lamarr may not have refined her invention, though her moral compass was questionable and she may be best remembered as Samson׳s sultry seductress (and one of the first to commercialize the female body), there was certainly more to this screen legend than meets the eye.

9 THINGS YOU DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT HEDY LAMARR