Judaean Mystery: Junk or Jewels?

Maresha is an archaeological oddity. First of all, nobody’s heard of it, as it’s usually lumped together with nearby Beth Guvrin. Then there’s the fact that almost nothing of it remains above ground, but there are a good few square kilometers of dwellings in thousands of caves under the surface. Finally, digging in Maresha is somewhat like excavating a refuse dump – with the odd sensational piece of jewelry thrown in. But one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, especially in archaeology.

So which section of Maresha interests you? The ancient necropolis, best-known for its colorfully decorated Sidonian caves? The columbaria, with their hundreds of small, triangular alcoves carved out of the rock? Or the caves that were used as storerooms and workshops, providing an underground refuge from the heat?

But these are just the “popular” parts of Maresha. For the more adventurous, another Maresha has revealed itself inch by inch over thirty years of excavation. Dusty, backbreaking, and unglamorous, this place doesn’t beckon to the superstars of Israeli archaeology. There are no biblical remains to be found. The Israelites never even lived here, nor did their descendants. But in a way that makes Maresha all the more fascinating – and startlingly relevant. Because at its height, it was conquered by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus (137–104 BCE), and all its inhabitants – at least according to Josephus – converted to Judaism. Abandoned soon afterward, the town never recovered.

So Maresha is that rare site reflecting what happens when Jews constitute the dominant culture in the region and a non-Jewish city has to adapt – which wasn’t the case again here until 1948.

Everyman’s Excavation

Another unique thing about Maresha is that anyone can excavate there. The Archaeological Seminars Institute runs the “Dig for a Day” program, which allows tourists, schoolchildren, and anyone else who feels like it to excavate under the watchful eyes of its archaeologists and trained volunteers. This method has moved and sifted mind-boggling amounts of earth – a few hundred rooms, ranging from small baths to large halls, have already been uncovered. The reason archaeology can be undertaken here in this way is that at some point the caves became a dump. When things are randomly thrown down a big hole (and there are lots of large holes in the area, opening onto the original underground rooms), there’s neither rhyme nor reason to the way they settle, so there’s no point in looking for any.

Archaeologists call this a “non-stratified” site, meaning that what’s on top isn’t necessarily newer than what’s underneath. As a result, digging in Maresha is less obsessive than elsewhere. You don’t have to pinpoint to the millimeter where anything was found, as long as you know which room and cave system it came from. So less disciplined workers – kids, for example – can be accommodated too.

Archaeologists Ian Stern and Bernie Alpert have spent years discovering Maresha with Prof. Amos Kloner. Stern and Alpert set up “Dig for a Day,” working in conjunction with Hebrew Union College, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Stern is coordinating efforts to document the enormous amount of household pottery, ornaments, and refuse in all these caves. That’s another interesting aspect of Maresha – ordinary people lived here in an ordinary way, so the place is important for what it can tell us about their daily lives.

Stepping down into the past. The careful dressing of the brick-arched entrance to a house in subterranean complex 89 of Tel Maresha reveals the ancient builders’ skill

Archaeologists for a day. Young enthusiasts plumb the depths of Tel Maresha, digging up earth and often artifacts. Every bucket of dirt removed is finely sifted, so not even the smallest fragments are lost. In thirty years of excavation, thousands of cubic meters of earth have been dislodged this way

Who Lived Here?

Maresha is mentioned in the Bible as a fortified town built by Solomon’s son Rehoboam and home to a prophet named Micah, but most of the remains found here date from the third to second centuries BCE, when the Holy Land was ruled by the heirs to Alexander the Great’s empire, from fairly benevolent Ptolemaic kings to the more oppressive Seleucid regime.

In the second half of the second century, Maresha’s inhabitants probably witnessed the Hasmonean revolt, in which Judah Maccabee and later his brothers Jonathan and Simon established a semi-independent Jewish kingdom. Second Temple historian Josephus calls the people of Maresha Idumeans, descendants of Edom or Esau, and depicts them as desert dwellers concentrated in the south of the country.

As the Idumeans seem to have lacked a language or alphabet distinct from Canaanite, no texts have been attributed to them. The little we know of this population is based on archaeology and other folks’ impressions: a few passing references in the Bible, Josephus, and Egyptian and Assyrian inscriptions. The picture that emerges is of a fierce, warlike nation whose arid territory resisted agriculture and whose settlements straddled the caravan routes from Egypt to the Levant. Idumeans have been romanticized as desert guides and camel drivers, a vital link in the famed Incense Route used to transport balsam, salt, and other scarce commodities from the Dead Sea environs to destinations all over the ancient Near East.

Suffering under the Babylonian invasion that laid waste to Judea and exiled much of its Jewish population in the sixth century BCE, the Idumeans migrated to the Hebron area, where they inhabited such abandoned cities as Gat and Maresha. These were the Idumean towns supposedly sacked five hundred years later by Judah Maccabee, then reconquered after two generations by John Hyrcanus. As Josephus writes:

Hyrcanus also captured the Idumaean cities of Adora and Marisa, and after subduing all the Idumaeans, permitted them to remain in their country so long as they had themselves circumcised and were willing to observe the laws of the Jews. And so, out of attachment to the land of their fathers, they submitted to circumcision and to making their manner of life conform in all other respects to that of the Jews. And from that time on they have continued to be Jews. (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, book 13, Loeb Classical Library, vol. 5, pp. 356–7)

A generation later, John Hyrcanus’ son Alexander Jannaeus is described by Josephus as capturing Maresha once again, along with other Idumean towns, in his wars with the Samaritans. But the latest attributable remains found in Maresha’s lower city are lead weights dating to 107 BCE. After that the site seems to have been deserted, although it may well have been reestablished nearby, explaining Josephus’ continued focus on it.

To what extent did the Idumeans of Maresha actually accept Judaism? Did they become, as Josephus suggests, indistinguishable from Jews? Or were there perhaps similarities even before the conquest, indicating a shared culture? The answers might tell us a thing or two about the influence of Jews on a conquered people, and even about the long-term future of the Arab-Israeli conflict and the perils of conquest. So let’s see what the archaeological record has to say.

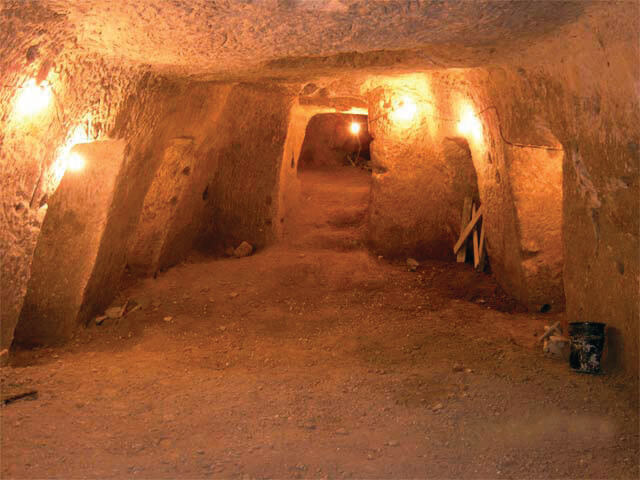

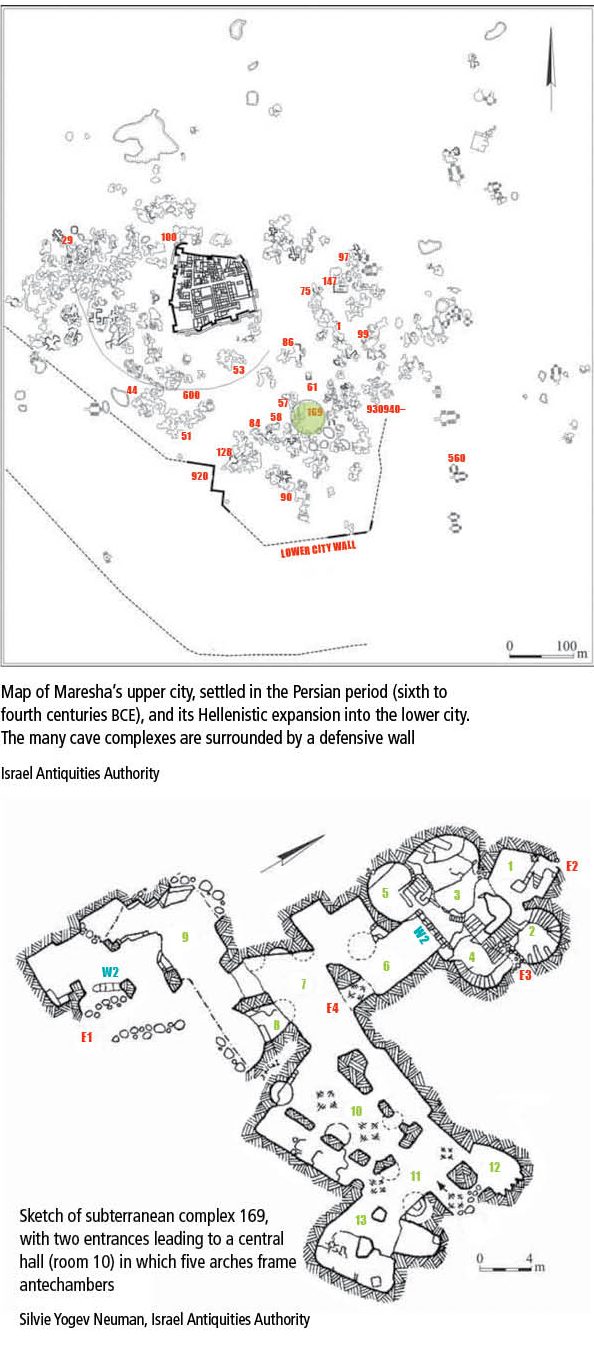

Basement Goddess

Maresha’s soft, chalky soil allowed for cheap, fool-proof home construction – and expansion. You quarried building blocks right on site, digging out your foundations, which quickly became your basement and storerooms (or your garbage dump). Need another room? Just keep digging, and either pass on the limestone to a fellow builder, or use it to build an above-ground extension. Consequently, though the houses here are mostly long gone, with only rare doorways and wall fragments remaining, the area is riddled with cave complexes (169 in the lower city alone!), which served as both quarries and dwellings.

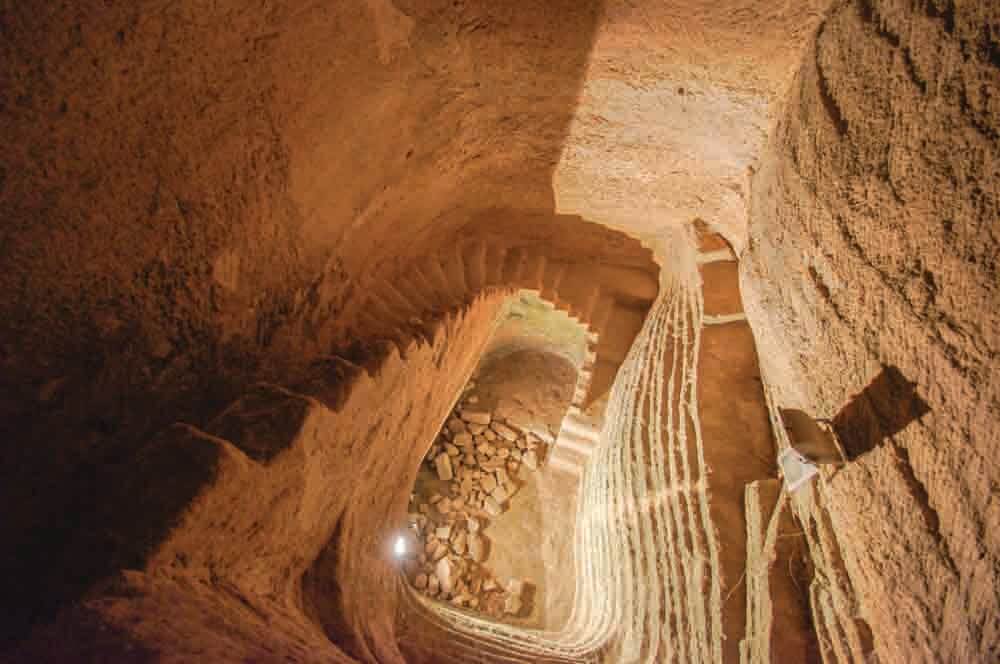

Evenly hewn steps spiral down into the depths of a storage room open to the public. The ridged walls suggest this cavern was a quarry, like most of the caves, before its conversion for secondary use Derek N. Winterburn

In times of trouble, the ease of tunneling through this rock made it natural to dig connecting passages, enabling Mareshans to wander around their town without ever venturing above ground. One set of tunnels, reached by crawling through a hole in the wall of complex 89, contained a whole collection of intact earthenware, apparently placed there for safekeeping.

This complex – one of the largest, with sixty-seven rooms – includes what appears to have been a temple. High up on the wall, a relief profiles a goddess sporting an Egyptian headdress. An adjacent cave housed an altar. The Idumeans who lived here, it seems, offered animal sacrifices and made visual representations of their gods.

Did these rituals change after the Hasmonean conquest? Sadly, we can’t answer, as almost no post-conquest remains have been found. If the Idumeans here did accept Judaism, they went elsewhere to practice it. And it looks as if someone actively tried to prevent their coming back, filling the subterranean rooms of their city with rubble and refuse.

The written record, mostly ostraca (inscribed pottery shards), is also inconclusive. The etchings found in complex 169 are mostly in Aramaic, suggesting the inhabitants were locals; the inscriptions in complex 89 are in Greek. Everyone in Second-Temple Judea spoke Aramaic, since it had been the lingua franca of the Babylonian and Persian Empires. Greek too was by the Hellenistic period an international language, not to mention the only hope of getting ahead. Further proof of its use in Maresha is the famous Heliodorus Stone, found in complex 57, inscribed in Greek and ordering a government inspection of all the temples in Judea. The story of how an emissary from Syria was divinely punished for carrying out a similar instruction appears in Maccabees II. (See “A Stele in the Temple,” Segula 8.)

So far, no clear evidence of Jewish influence. If anything, we seem to be tending the other way.

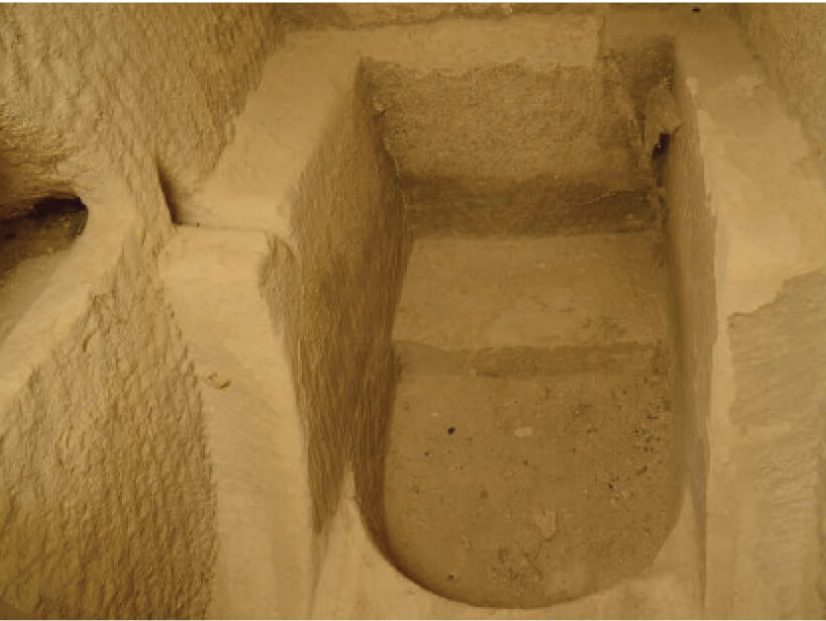

Ritual purification bath in Maresha, with a channel for pouring water onto the bather

Sidonian burial cave, Maresha. Though Idumeans seem to have provided the dominant culture, Maresha‘s population included Sidonians (of Phoenician origin), Hellenists, Jews, and even Egyptians. The artistic style of this richly decorated burial cave is clearly Phoenician, but Hellenistic influences are also apparent

Doves or Chickens?

Several archaeological parameters distinguish a Jewish settlement from a non-Jewish one. The most obvious is the small percentage of bones from either domestic pigs or wild boar, showing that at least some Jewish dietary restrictions were observed.

Sifting through the refuse of Maresha has produced plenty of animal and fowl bones, but few from pigs. Thirty percent of these bones are from chickens, an unusually high proportion for the period. This anomaly goes along with another unexplained phenomenon of Maresha: the columbarium caves.

Over eighty-five such caverns, hollowed out with row after row of triangular apertures numbering in the hundreds, have been found in Maresha – the highest concentration in Israel. The conventional wisdom is that they were used to raise doves, which were eaten (along with their eggs) or sacrificed, with their droppings serving as fertilizer. But might these holes have housed chickens instead?

The chicken is thought to have been introduced in the Middle East by the Phoenicians, spreading south from Syria in the middle of the second millennium BCE, and Maresha is certainly full of chicken bones. Determining whether hens were eaten or kept for their eggs, however, isn’t so simple.

The holes of the columbaria extend all the way up to the cave roofs, a setup hardly designed for low-flying chickens. One might argue that doves’ frail skeletons are naturally hard to find after a couple of thousand years, but the sifting method used in Maresha has successfully isolated items as small as a glass bead, so the fact that there are loads of chicken bones and no doves to speak of in Maresha pokes a fairly substantial hole in the dove-raising theory. The crucial question: who invented chicken soup, the Jews or the Idumeans?

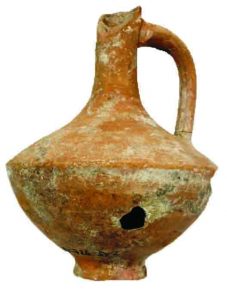

Holey Pots

Another archaeological marker of a Jewish settlement is the discovery of stone eating and drinking vessels. According to Jewish law, stone cannot become ritually impure, whereas ceramics that come into contact with impurity (in the form of a dead insect, a corpse, or a menstruating woman, for example) can never be used again. Few such vessels have been found in Maresha, in significant contrast with Jerusalem and Jericho, for instance.

What about ritual baths, which also reflect concern with purity? Though baths have been hewn into the rock in at least twenty caves, most of these installations don’t conform with the requirements of a mikveh. Instead, someone had to pour water onto the bather, albeit discreetly, through channels and spouts. Excavations conducted by archaeologists Bliss and Macalisters in 1900–1902 did unearth two baths with steps leading down into them, as required for a mikveh, but were these pools connected to the requisite source of rainwater or spring water? The pair left no records of such a system.

So far, our local Idumeans have little in common with Jews in terms of ritual purity. There is, however, one puzzling feature in some of the pottery uncovered here. Many ceramic pots are punctured. The Mishna in tractate Kelim (Vessels) describes a method of salvaging impure pottery:

Ceramic and leaden vessels … their breaking [alone] effects their purification. (Kelim 2:1)

The Mishna (3:1, 3) goes on to explain that a punctured pot is considered broken, because it’s unusable.

Could all these punctured receptacles have become impure (through contact with a dead insect or rodent, for example), then “broken,” permitting their continued use? The punctures found in Maresha are generally smaller than the 2.5-cm diameter of a Syrian olive prescribed in the Mishna, but not significantly so. Similar pots dating from the Roman period have been recovered near the Temple Mount and elsewhere in Jerusalem’s Old City, and others in Kiryat Ata and Tel Beit Mirsim, though these hark back to the Bronze and Iron Ages. In Sylchester, England, seventy-five such punctured vessels were recorded, dating from the Iron Age and Roman era. But there are probably many more unrecorded examples, since archaeologists aren’t generally on the lookout for leaky pottery!

These holes were clearly deliberate, making both jug and dish unsuitable for normal use. Was that the intention, and if so, was this an act of purification?

One theory is that pots used for sacrificial meat were punctured to ensure they weren’t returned to regular use. But surely it would have been much easier to smash them, as the Mishna suggests. In a forthcoming article, “The Holey Vessels of Maresha,” Aram 27 (2016), Ian Stern and Vered Noam note that a majority of the punctures are found in “dinnerware” rather than cookware, that punctured vessels formed a much higher percentage of the ceramics found in tomb 559 (where ritual events were more likely to take place) than anywhere else, and that the phenomenon appears not only outside Jerusalem but outside Israel, implying a universal practice connected with feasting. Dishes used for a ritual banquet might have been considered too holy for either mundane purposes or destruction. Puncturing might therefore have been the solution.

So were the Idumeans here following a Jewish custom, or did the Jews’ neighbors simply develop similar rituals? Perhaps another cross-cultural cultic practice will one day explain whether these holey pots were holy as well. Meanwhile, the evidence from Maresha is, in a word, mixed – like its population, it would seem.

Thirty years of excavation here have yielded more questions than answers, and an awful lot of ceramics. So if you ever feel like getting your hands dirty, there’s always room in Maresha for another amateur archaeologist. It’s not the City of David, where names from the Bible jump straight out of the earth, but if you’re satisfied with learning about the cultural diversity of ancient Judea, you never know what you might find.