Migrant Melodies

Though American music has long been defined in terms of black or white, depending on its community of origin, there are also shades of gray. Nineteenth-century Irish composers gave American popular music lilt, and Italian singers have also made their mark. It took a while for these ethnic influences to penetrate America’s WASP elite, but from the 1880s onwards, Jews were disproportionately overrepresented in the emerging music industry.

Few of his contemporaries saw the potential of black musical styles such as jazz. Gershwin at the piano. The painting of a black girl on the wall above him is his own work

Today we take the vocal virtuosity of black divas, the wail of the blues, and the ecstasy of gospel for granted, but the music must have grated on the conservative ears of post-Civil War whites. Overall, American music is largely the product of black-Jewish collaboration, a cultural blend also manifest in the struggle for civil rights.

As Europe’s Jews fled the slaughter engulfing them, Jewish Americans were creating a new musical genre. If German composer Richard Wagner had attributed the mediocrity of 19th-century music to its many Jewish contributors, then the Jews’ reinvention of American music was their revenge. They wrote the popular ragtime melodies, the hit Broadway musicals, the movie soundtracks, the groundbreaking jazz operas, and the folk and blues of the civil rights movement. Their music projected the America they dreamed of: liberal, multi-cultural, cosmopolitan; a land of opportunity for all, regardless of race, creed, or gender. To quote Ira Gershwin, they “built a stairway to paradise.”

Black Like Me

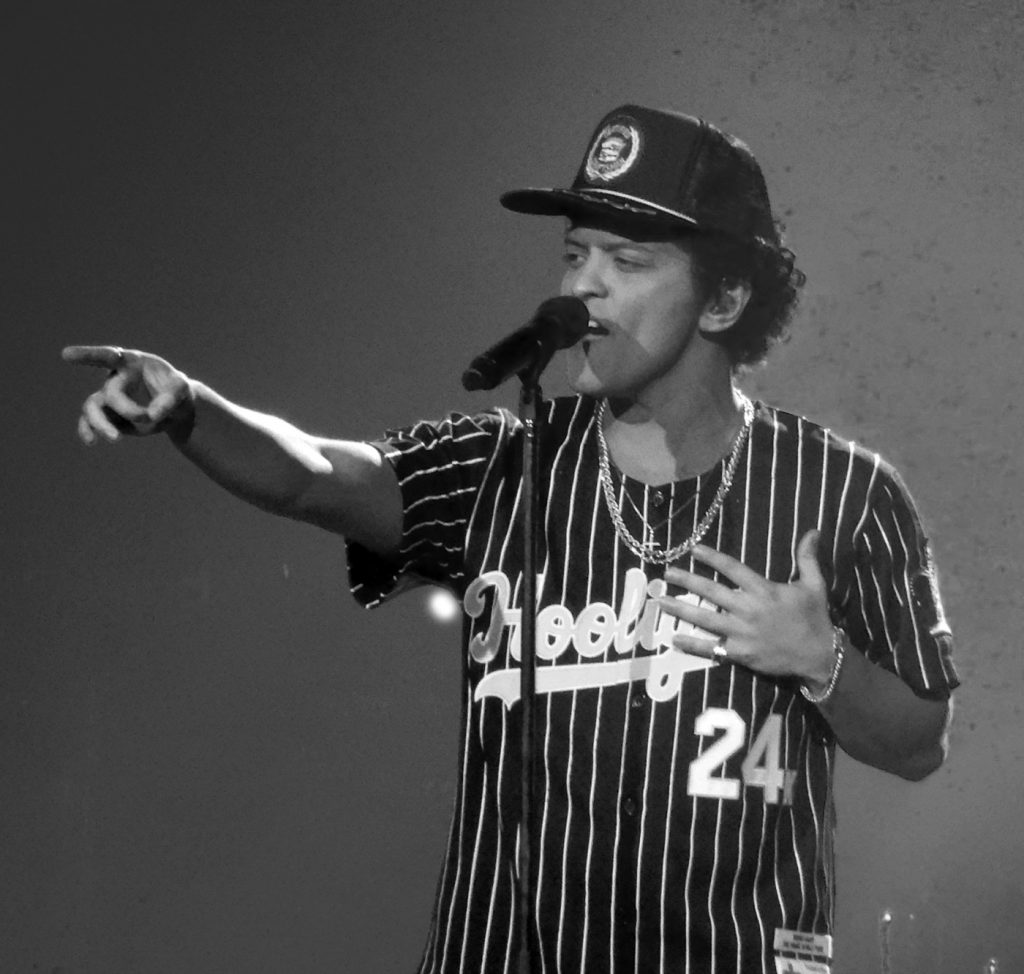

“Uptown Funk” (2014) has been one of this decade’s biggest hits. Recorded by Jewish producer Mark Ronson and vocalist Bruno Mars, who also has Jewish roots, the single is full of black slang. Though it sounds like updated 1970s funk , the song typifies an aspiration shared by white pop music composers and performers over the last century – to be, as Norman Mailer put it, “white Negros.” The timbre of black vocals, the Afro-American beat, and the aura of “black cool” represent the ideal. Pop music reflects a kind of inverted racism: “black” is considered the real deal, while “white” is just a wannabe. Jewish musicians played an important part in promoting this perspective; as composers and performers, they built the American music industry on the foundations of black musical culture.

Opportunity Knocks

Jews ventured into show business first and foremost as entrepreneurs. All six of Hollywood’s major movie studios were famously founded by first- or second-generation Jewish immigrants. But Jews were just as involved in the music industry. Music was neither particularly profitable nor respectable in the 19th century, attracting little investment or interest. But as vaudeville gained popularity in New York during the 1880s, and copyright became law in the 1890s, conditions were ripe for songwriters to rake it in. Suddenly, with one hit, lyricists and composers could be set for life – and make a profit for their music label too.

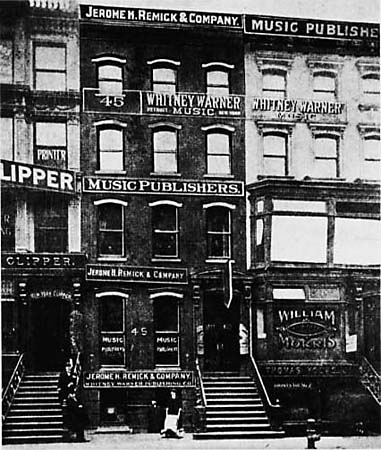

In Gershwin’s day, the music industry centered on Tin Pan Alley, as this stretch of Manhattan’s 28th Street was known

From 1880 to 1920, over two and a half million Jews disembarked on America’s East Coast. Most settled in the urban centers, especially New York, where they formed the city’s largest ethnic minority, peaking at just under a third of the population in 1925. Though the United States was paradise compared to the seething anti-Semitism of Europe, Jews weren’t welcomed everywhere. Heavy industry, Wall Street’s most prestigious firms, and the leading universities were all off limits, forcing American Jewry to find alternative avenues of advancement – niche industries just then coming into their own. One such was the garment trade, and entertainment was another. Generally speaking, Jewish immigration to the U.S. was incredibly successful, coinciding with the rise of American capitalism, which fit these newcomers like a glove. Their success may well have prompted the elites to stop mass immigration in the 1920s, raising hurdles for further potential arrivals.

American Jews, especially those of German origin, were among the pioneers of music publishing in New York, employing marketing strategies used in their previous lines of work. The music labels located themselves around Broadway, opening small companies to write, produce, and distribute songs as sheet music – the only way to get them out there before widespread use of the gramophone. Jewish journalist Monroe Rosenfeld dubbed the area “Tin Pan Alley” for the cacophony of singing and piano playing echoing from the studios. In the first half of the 20th century, the name became synonymous with American pop music.

Alley Cat

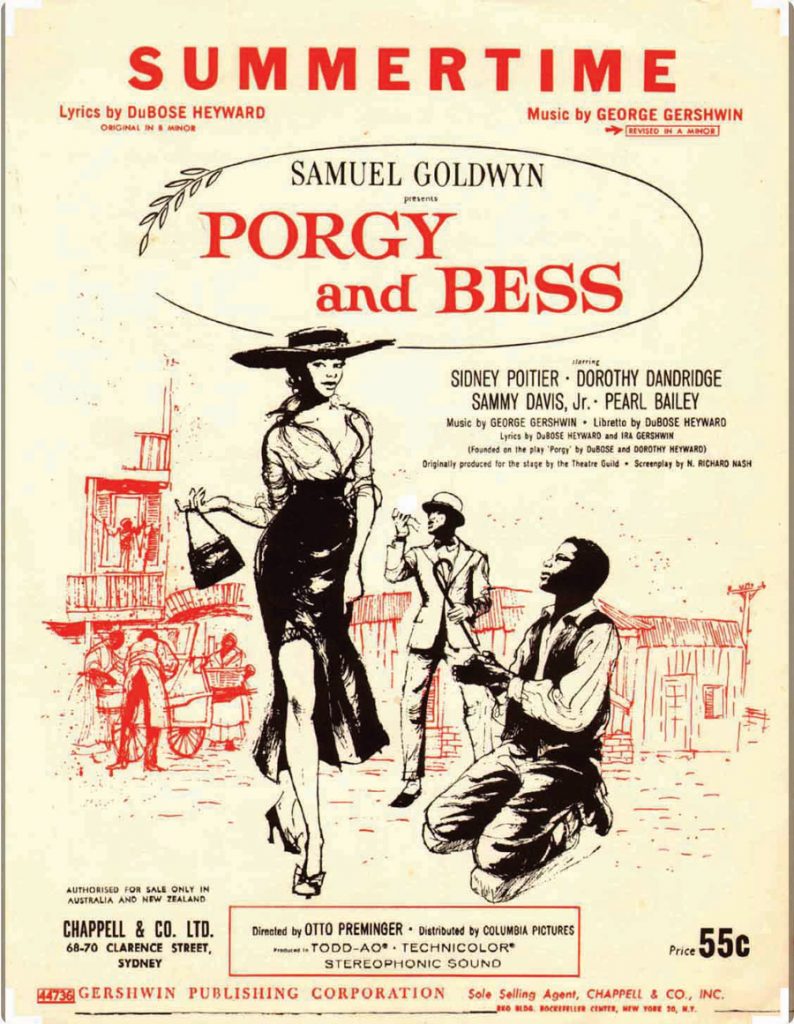

Tin Pan Alley was where George Gershwin started his career. Both his parents were Russian immigrants who’d married in America and changed their name from Gershowitz to Gershwin. George was born Jacob in 1898, two years after his brother Ira (Israel). Ira later became George’s partner, writing lyrics to popular songs and musicals, including parts of Gershwin’s groundbreaking opera, Porgy and Bess. Though they struggled financially, the Gershwins made sure – like many other Jewish families – that their children grew up in a secure and cultured bourgeois environment, speaking English rather than Yiddish.

George’s biographies describe him as a hyperactive twelve-year-old street kid entranced by the piano from the moment his family acquired one. He had a natural talent, playing by ear. Though he took piano and composition lessons, his only musical higher education consisted of two courses at Columbia University. One instructor, pianist Charles Hambitzer, declared him a jazz-mad genius – and that was even before the first jazz recording came out in 1917! Hambitzer schooled his pupil in the basics of modern classical music, but George sought inspiration elsewhere. He was influenced by the Yiddish theater, befriended pianist and composer Leslie C. Copeland, and early in 1915 detected the beginnings of jazz in the work of African American musicians. Their Harlem Stride Piano style was similar to ragtime but harder to play.

Gershwin saw black trends as the basis of the developing American music scene. He knew which side he was on in the debate raging between conservative WASP composers and proponents of modernist multiculturalism. In many ways, the avant-garde won out, coming to dominate both classical and popular music, and embedded Afro-American elements firmly within the American musical tradition.

Masters or Equals?

Gershwin and his ilk raise two interesting questions. Why were Jewish composers drawn to black music, and who gained most from the subsequent Jewish-black collaboration? Over the years, two schools of thought have emerged to explain the affinity between the two minorities.

The first suggests a shared history of victimhood: the black experience of exile, slavery, and suffering echoed the Jews’ collective memory of biblical enslavement and generations of persecution.

The second claims that light-skinned

American Jews blended easily into WASP culture and promoted a white-dominated melting-pot society, exploiting black artists for their own benefit. Case in point: The Jazz Singer, a play and film that revolves around jazz without even mentioning – let alone including – a single black character. It was a Jewish story set to black music.

In The Jazz Singer, Al Jolson starred as a cantor’s son who dreamed of a show business career. Poster for the movie

Neither approach is wholly accurate. Jews weren’t entirely altruistic or unscrupulous in dealing with black artists. In the early 20th century, Jews in show business clearly defied the white elite, creating a less puritanically sanctimonious public square. Yet the new brand of humanism these composers and lyricists championed was also elitist; believing they knew best, they molded both pop culture and the fine arts in their own image.

Seeking raw material, they discovered the enormous potential of black music. Jews immediately felt at home with its poignancy and passion, which recalled the haunting melodies of the eastern European synagogues. Indeed, some of the most famous Jewish American composers were cantors’ sons, familiar with improvisation within a traditional context. That said, there were certainly some cases of exploitation, whether economic or cultural. George Gershwin was by no means the only one accused of wantonly ransacking the black musical heritage.

Starting Small

Like many other musicians, Gershwin started out in Tin Pan Alley – first pitching songs to popular singers, hoping they’d perform them, then as a sought-after songwriter shuttling between the various music publishers. The resulting social and business connections became the basis of his career.

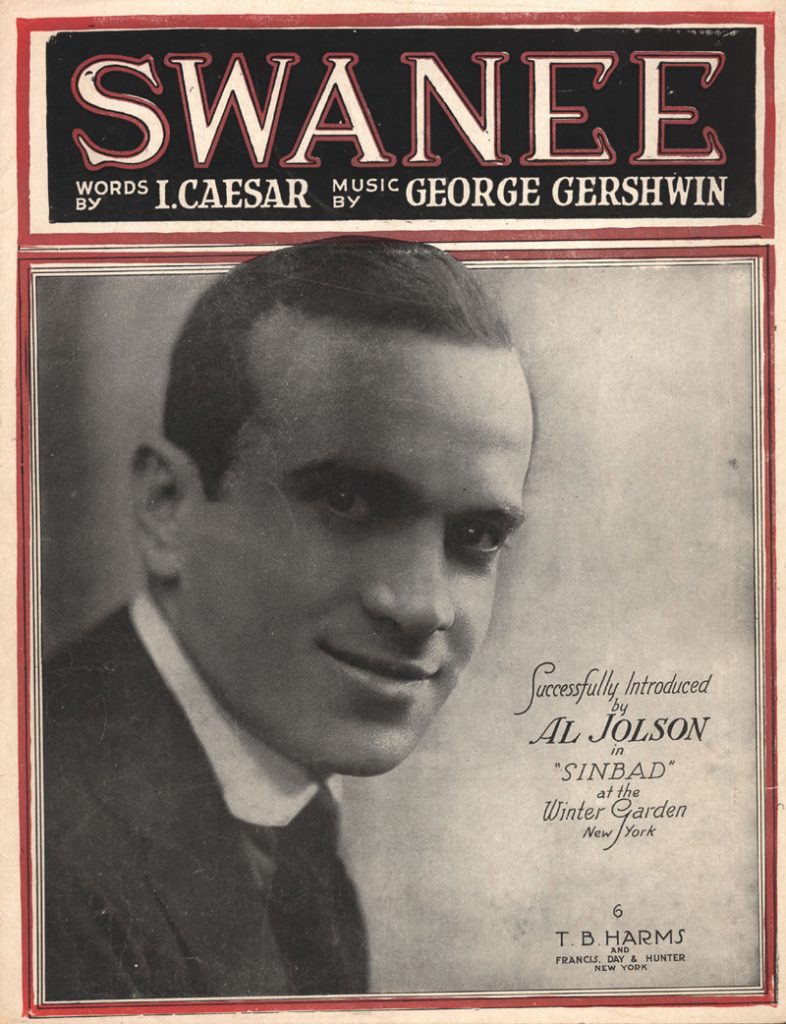

In 1919, singer and actor Al Jolson, who’d starred in The Jazz Singer, heard Gershwin’s song “Swanee” (with lyrics by another Jewish artist, Irving Caesar) and included it in one of his musicals. The tune drew on the minstrel tradition, and Jolson was the greatest minstrel of his time.

In The Jazz Singer, Al Jolson starred as a cantor’s son who dreamed of a show business career. Jolson, blacked, on stage

George Gershwin had written “Swanee” at home, and his father, Morris, had joined him at the piano, improvising with a piece of paper and comb.

Music to play, not to listen to. Before the gramophone became widespread, new songs were printed as sheet music and sold like any other publication. Gershwin’s hit “Swanee”

Gershwin composed concert music as well as hits, and his work in each genre fed off and infused the other. His career divides roughly into three: his early period, climaxing with his classical sensation, Rhapsody in Blue, in 1924; his mature, romantic years, when he wrote the majority of his classical pieces and musicals; and the final stretch, in which he produced most of his masterpieces. This last phase began in the 1930s with “I Got Rhythm,” one of the most influential jazz pieces in history, and peaked with his epic jazz opera, Porgy and Bess (1935), which boldly depicted the black experience as an essential part of America’s soul.

Just before Gershwin’s thirty-ninth birthday, a brain tumor tragically took his life, cutting him down in his prime.

Rhapsody in Black

Porgy and Bess was revolutionary, and not just in celebrating black life. Its story line jumbled past and present, and America, Africa, and Europe; the score was theatrical, its musical motifs pioneering. And the show preached social awareness and justice. Depicting African-American life as part of the American experience, Gershwin portrayed racism in all its ugliness, hoping to eliminate this national scourge. As a Jew, he appreciated the art and culture of a fellow downtrodden minority. Avoiding stereotypes, he cast blacks in a positive though realistic light (too realistic, some claimed) while exposing how white society abused them. He insisted on putting black singers on stage, showcasing the full range of their talents. The unique power of black music should speak for itself, Gershwin observed in 1925:

I think it [jazz opera] should be a Negro opera […]. Negro, because it is not incongruous for a Negro to live jazz. It would not be absurd on the stage. The mood could change from ecstasy to lyricism plausibly, because the Negro has so much of both in his nature. (Howard Pollack, George Gershwin: His Life and Work [University of California Press, 2007], p. 567)

Looking for a suitable libretto, he wrote:

I shall write it for niggers[!]. Blacks sing beautifully. They are always singing, they have it in their blood. They have jazz in their blood too, and I have no doubt that they will be able to do full justice to a jazz opera. (Pollack, p. 568)

As the idea of a jazz opera germinated in his mind, Gershwin picked up American novelist DuBose Heyward’s Porgy one day in 1926, a year after its publication. Its humor and suspense kept him reading all night. The next morning, he wrote to Heyward that he’d like to adapt it as an opera.

Then a promising Southern writer, Heyward described black life, focusing on Porgy, a lame Afro-American beggar. Spirituals and snatches of Gullah, the patois used by blacks in the South, added to the text’s authenticity.

Gershwin read DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy and immediately knew he’d found the story line for his dream musical. Heyward and wife Dorothy

Gershwin had already written a show about black culture, Blue Monday, but it flopped. That made him more careful with Porgy and Bess. Despite his initial enthusiasm, he took nine years to get it right, culminating in a Boston premiere in September 1935.

When he started writing Porgy, Gershwin was churning out one musical after another, even considering basing an opera on The Dybbuk, S. Ansky’s Yiddish play, with its rich folklore and Jewish mysticism. In 1933, unable to acquire the rights to that work, he turned to finishing the jazz opera he’d begun. The experience he’d gained meanwhile added to his versatility, allowing him to blend his skills in classical composition, songwriting, and musicals into one mature work that would sum up his varied background. Gershwin spent almost a year composing the music and another nine months orchestrating it.

Local Color

Gershwin and Heyward collaborated on the production, determined to engage only classically trained black singers and avoid the “blackface” then prevalent in minstrel shows. Striving for authenticity, the pair even decided against casting Al Jolson, though his participation would have assured the show’s funding, and though he’d been instrumental in advancing Gershwin’s early career.

In late 1933 and early 1934, Gershwin and Heyward spent a few days in Charleston, South Carolina, soaking up the local color. Gershwin wrote to Heyward beforehand:

I would like to see the town and hear some spirituals and perhaps go to a colored cafe or two if there are any. (Pollack, p. 577)

The composer was particularly struck by the atmosphere in the town’s markets, whose hubbub perhaps reminded him of the Jewish neighborhood in Manhattan’s Lower East Side and the hymns he heard echoing from the churches in the area.

The busy markets may have reminded Gershwin of the bustling Jewish neighborhoods of Manhattan’s Lower East Side

That summer, seeking more of a feel for the South, Gershwin joined Heyward and his wife on Folly Island, about ten miles from Charleston. There was even a Jewish delicatessen. Gershwin rented a spacious beach house, installed a piano, and immersed himself in local folk culture, jamming with vocal groups and street musicians. On his way home to New York, he and Heyward heard a black group singing twelve-part harmony in Hendersonville, which left its mark both on the composer and on Porgy and Bess.

The show is a deeply charged encounter between songwriter and setting. Scene by scene, theme by theme, complex harmonies bring to life a community riven with all kinds of human strengths and weaknesses: faith and brotherhood; violence, grief, and prejudice – but no racism. It’s a multilayered experience, from the opening fugue to the Yiddish and black leitmotifs of the lullaby “Summertime” and the almost direct quotations from Gershwin’s concert pieces. Porgy and Bess echoes classical themes by Claude Debussy, Giacomo Puccini, Jerome Kern, Igor Stravinsky, and Alban Berg as well as the Afro-American jazz melodies of W. C. Handy, Cab Calloway, and Duke Ellington. It pays tribute to Afro-American spirituals and Yiddish music too, and some even hear strains of the Hebrew folk song Heveinu Shalom Aleikhem in “It Takes a Long Pull to Get There.”

The score ranges from simple to sublime, and many arias topped the charts despite their operatic origins. In fact, purists dismissed Porgy and Bess as too popular to be serious opera, but Gershwin countered that Verdi’s works all included some hit songs, while Bizet’s Carmen was one after another! Even Leonard Bernstein, who’d criticized Gershwin’s classical compositions, wrote:

With Porgy you suddenly realize that Gershwin was a great, great theater composer. […] Perhaps that’s what was wrong with his concert music. (Leonard Bernstein, The Joy of Music [Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1960], p. 62)

Pianist Oscar Levant, one of Gershwin’s close friends, reported that the composer listened to a lot of Wagner while writing Porgy. We can imagine what Wagner would have thought of a Jewish opera, but the Afro-American response was surprisingly negative. Though the opera’s black actors were moved to tears, other African-Americans were scathingly critical. Duke Ellington reputedly declared the music inauthentic and suggested it was time to wipe the soot off Gershwin! Yet Ellington loved the 1952 revival, staged after the composer’s death. In the sixties, radicals such as Harold Cruse derided the work’s stereotypes.

To this day, Gershwin’s heirs allow only black actors to perform Porgy and Bess. Scene from the 1959 movie

Despite his critics, George Gershwin’s contribution to popularizing black music cannot be denied. Plenty of black artists still see Porgy and Bess as a jazz classic, and Gershwin’s songs have remained a staple of their repertoire to this day.