Ancient But Sophisticated

Many tribes filled the Arabian Peninsula two thousand five hundred years ago, but virtually none of their names have survived. The same would doubtless be true of one particularly industrious and ambitious clan, had it not wandered north toward the Mediterranean coast in the fourth century BCE, near the end of the Persian period. The tribe’s name back then? No one knows. But this people’s distinguishing characteristics included a ban on alcohol, a nomadic lifestyle, and an uncanny instinct for finding its way through the desert.

From their trading partners in Sheba, the tribesmen learned how to channel the desert’s rare floodwaters into hidden water holes, and to lead long camel caravans through any weather. Their mastery of the terrain gave them exclusive control of the overland trade routes linking the main ports along the Dead Sea, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean. The goods they carried included perfumes and spices from India, especially the myrrh and frankincense so prized in Europe; silks and satins from the Far East; salt, then worth more than gold, and far more useful; and even asphalt from the Dead Sea, which the Egyptians used to embalm their mummies.

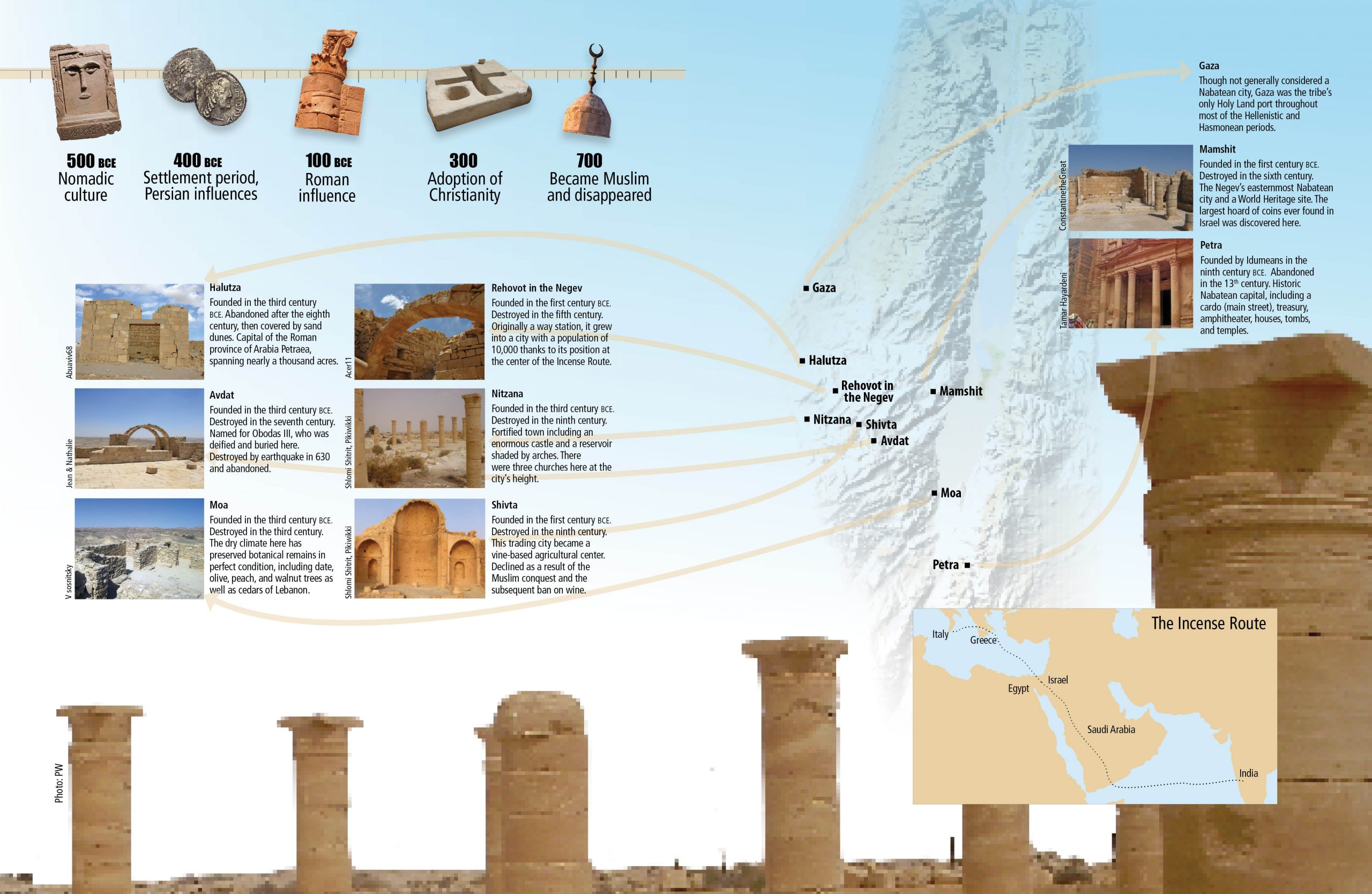

The tribe’s main trading arteries were known collectively as the Incense Route. Caravan stops, inns (khans), and forts were spaced along it at twenty-kilometer intervals – one day’s journey by camel. Here travelers could stock up on food and water, replace injured or tired camels, and even stay overnight. The whole operation was so professional that the clan’s courier services were soon in high demand, making it extremely wealthy.

The classic façades carved out of Petra’s red rock make it one of the most impressive man-made sites in the world

Boundless Riches

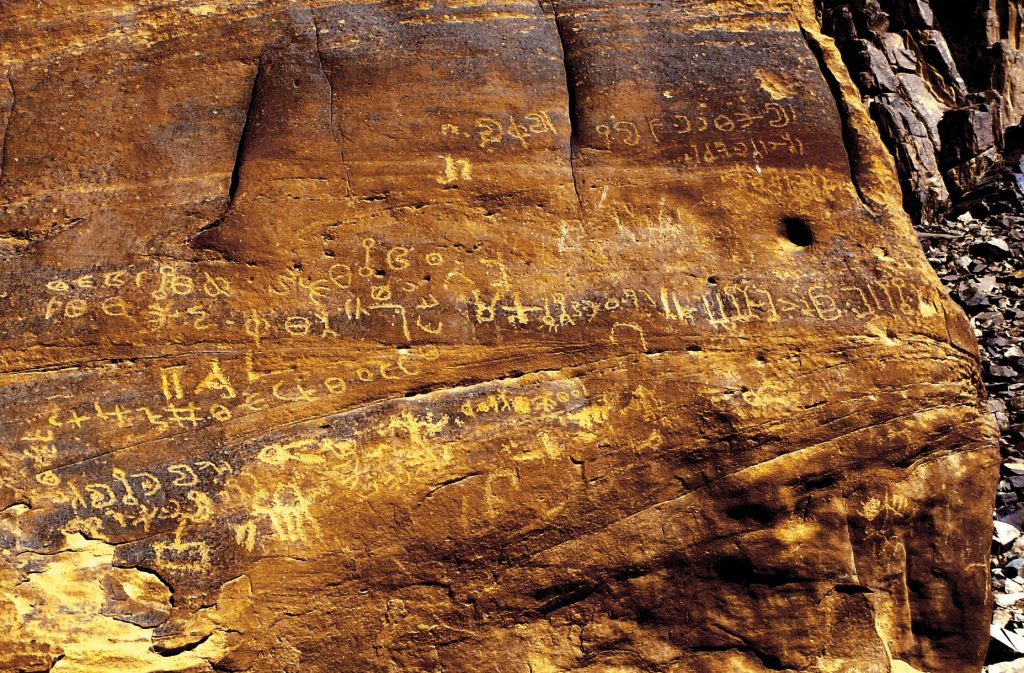

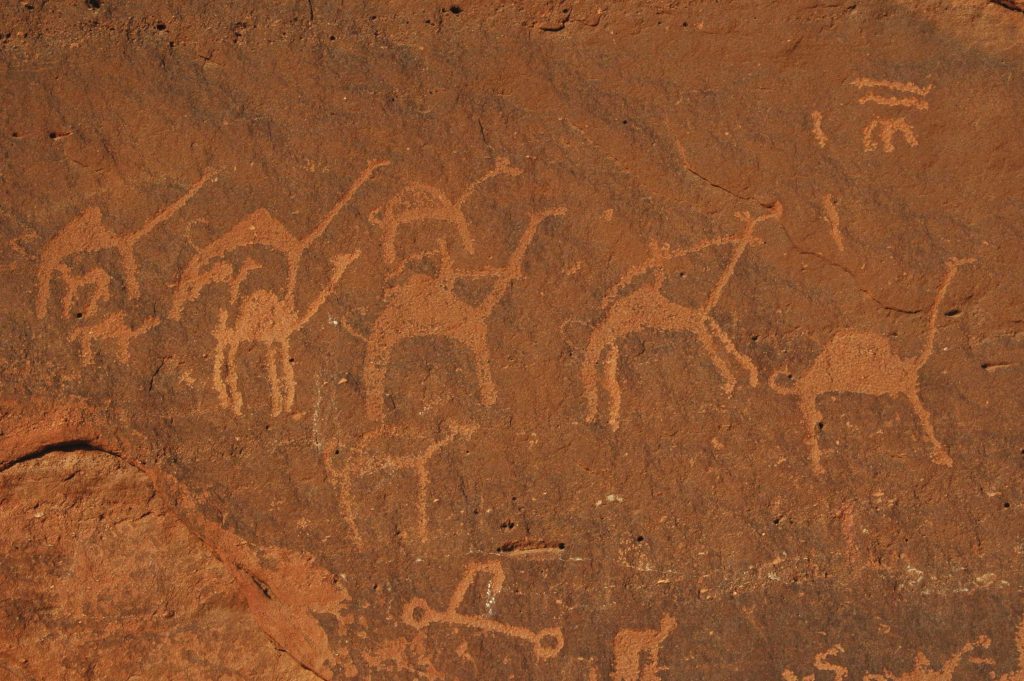

Very little is known about the tribe’s culture and history, for none of it was recorded. Most of our information comes from the clan’s adversaries or trade partners and from Greek and Roman historians, who’d only heard about the people in question secondhand. From pictograms and names of gods etched on rocks along their trading routes, we know they were pagans, like most Arabians prior to the rise of Islam. In Wadi Rum in Jordan, close to the ruins of the tribe’s temples, rock drawings portray the Arabian mountain god Dushara, Al-Uzza, goddess of love, and Manat, moon goddess of fate and fortune.

For generations the tribesmen were nomads, resisting all temptation to settle down, but eventually it became impractical to wander through the desert with thousands of women and children. They sought a site large enough to hold them, hidden but at the center of their caravan routes, where they could safely house their families and – equally important – their treasures.

This settlement program went into action in the fourth century BCE, when the tribe conquered the Idumean city of Petra, nestled deep in the canyons east of the Jordan River, in the hills of Edom east of Eilat. From this modest beginning, the clan built permanent homes, towns, and even cities. Taking over more and more of the Idumeans’ territory, the tribe eventually drove them westward into Judea. Before long the conquerors were dispersed over northern Arabia, the east bank of the Jordan, southern Syria, the Negev, and the Sinai Peninsula.

In the meantime, the wars of the Diodochi, heirs to Alexander the Great’s Hellenist empire, were tearing the region apart. Securing Judea, the Diodochi turned their attention across the Jordan, hoping to enslave the area’s inhabitants. This is when the tribe’s name first appears in an inscription. The Greeks called these folk Nabateans, perhaps from the Arabic nabatu, which means carving or digging, alluding to the tribe’s remarkable talent for finding and storing water in the desert. Greek attempts to conquer the Nabateans failed – as did other enemy attacks over the years. None could overcome these lords of the desert, thanks to their ability to hold out despite parching heat by day and bitter cold by night.

As Nabatean culture spread throughout the Middle East, trade between ports improved, and major thoroughfares were dotted with Nabatean way stations. Ornamented with stone flourishes and graceful temples, Nabatean cities included intricately carved tombs, particularly in the necropolis of their hidden capital, Petra. With wealth and security came such technological advances as the art of firing eggshell-thin earthenware.

Just three hundred years after leaving the Arabian Peninsula, the tribe had become a strong, confident nation ruled by its own king.

The origins of the Nabatean royal house remain unknown, but a rock inscription at Halutza in the Negev, immortalizing founding monarch Aretas I, has been dated to 168 BCE, just before the Maccabean revolt in Judea. Second Maccabees also refers to “Aretas, king of the Arabians” (book 5, ch. 8), who conspired to overthrow the Jewish high priest Jason. As Jason threatened to turn Jerusalem into a Greek city, any enemy of his was a natural ally of the Hasmonean rebels, who were delighted when he fled across the Jordan.

The Nabatean kings struck their own coins, complete with portraits. But in a nod to the Persian Empire, which used Aramaic as its official language, the coins were inscribed with Aramaic letters rather than the Nabatean alphabet, which eventually evolved into Arabic.

Rock drawings and inscriptions found in Wadi Rum – the longest and deepest stream bed in Jordan – testify to an early Nabatean presence. Prehistoric remains from the area show that humans have been active here for at least twelve millennia

In the meantime, the wars of the Diodochi, heirs to Alexander the Great’s Hellenist empire, were tearing the region apart. Securing Judea, the Diodochi turned their attention across the Jordan, hoping to enslave the area’s inhabitants. This is when the tribe’s name first appears in an inscription. The Greeks called these folk Nabateans, perhaps from the Arabic nabatu, which means carving or digging, alluding to the tribe’s remarkable talent for finding and storing water in the desert. Greek attempts to conquer the Nabateans failed – as did other enemy attacks over the years. None could overcome these lords of the desert, thanks to their ability to hold out despite parching heat by day and bitter cold by night.

As Nabatean culture spread throughout the Middle East, trade between ports improved, and major thoroughfares were dotted with Nabatean way stations. Ornamented with stone flourishes and graceful temples, Nabatean cities included intricately carved tombs, particularly in the necropolis of their hidden capital, Petra. With wealth and security came such technological advances as the art of firing eggshell-thin earthenware.

Just three hundred years after leaving the Arabian Peninsula, the tribe had become a strong, confident nation ruled by its own king.

The origins of the Nabatean royal house remain unknown, but a rock inscription at Halutza in the Negev, immortalizing founding monarch Aretas I, has been dated to 168 BCE, just before the Maccabean revolt in Judea. Second Maccabees also refers to “Aretas, king of the Arabians” (book 5, ch. 8), who conspired to overthrow the Jewish high priest Jason. As Jason threatened to turn Jerusalem into a Greek city, any enemy of his was a natural ally of the Hasmonean rebels, who were delighted when he fled across the Jordan.

The Nabatean kings struck their own coins, complete with portraits. But in a nod to the Persian Empire, which used Aramaic as its official language, the coins were inscribed with Aramaic letters rather than the Nabatean alphabet, which eventually evolved into Arabic.

The First Arab-Israeli Conflict

At first, the newly established Hasmonean kingdom was on good terms with the Nabateans. Josephus describes how they worked together to relieve Hellenist pressure on the Jewish population of the Galilee :

As for Judas Maccabaeus and his brother Jonathan, they crossed the river Jordan, and after covering a distance of three days’ march from it, they came upon the Nabataeans, who greeted them peaceably. And they told him what had happened to those in Galaaditis, and that many of them were in distress after being shut up in the fortresses and cities of Galaaditis; and when they urged him to march speedily against the foreigners and to try to save his countrymen from them, he followed their advice. (Josephus Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews XII, Loeb Classical Library, vol. 365, p. 75)

But the ties between the Jews and Nabateans were based not just on their mutual hatred of the Seleucid Hellenists, but on the fact that there was ample space for each kingdom. The Hasmoneans were concentrated in northern and central Judea, while the Nabateans lived south of the province, in the Negev, and in much of today’s Jordan. Once the Hasmoneans started expanding under King Alexander Janneus, they were in open competition. Janneus’ forces invaded Nabatean territories east of the Jordan, conquering cities and forts and imposing taxes. The same campaign destroyed Gaza, the Nabateans’ main port, as the king attempted to disrupt their trading and drive them from the region.

The assault was indeed a major blow. Camel caravans coming from the Red Sea expecting to offload their merchandise in Gaza and watch it set sail for Europe were forced to backtrack. Their new, longer route went through the Moabite mountains and the Gilead to the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon.

Not ones to suffer in silence, the Nabateans declared war. Their third king, Obodas I, defeated the Hasmoneans in the Golan and managed to win back some of his lost cities across the Jordan. His successor, Aretas III, went further, encroaching on Hasmonean territory and threatening to attack, only to be bought off with a peace treaty.

Things went from bad to worse. Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, the warring sons of Alexander Janneus, each sought Nabatean aid in their struggle for succession. In 65 BCE the Nabatean army entered Jerusalem and besieged the Temple Mount, where Aristobulus was holed up, although it was the Romans who ultimately put an end to the Hasmonean kingdom by appointing Herod as a vassal-king. They took the opportunity to invade Nabatean territory too, but like many before them, they were forced to retreat.

The Romans continued trying to defeat the Nabatean kingdom for decades. In 30 BCE, Obodas III, a contemporary of Herod the Great, took the Nabatean throne. Relations between the two were tense, partly because Herod, though an Idumean and appointed by Rome, had a Nabatean mother, Cyprus.

In the end things sorted themselves out, and Obodas’ reign marked a golden age of Nabatean culture. With Herod’s permission, he rebuilt the port at Gaza, and camel caravans wended their way through the Negev once more. Obodas’ admiring subjects created a new city in the Negev and named it Avdat, after him; he may well have been buried there too.

Wiped off the Map

How did the seemingly invincible Nabateans suddenly disappear with barely a trace? It seems they were culturally overwhelmed by their many trading partners. Egyptian, Greek, and Roman influences began appearing in Nabatean construction, and Aramaic diluted the nation’s Arabic dialect. Assimilation and intermarriage followed; even Obodas IV’s daughter wed Antipas, Herod’s son. Furthermore, Roman feasting customs overrode the Nabateans’ veto on drinking wine, as evidenced by the many winepresses found in their cities. In the first century, Greek historian Strabo noted the quantities of wine served at Nabatean banquets:

The king holds many drinking bouts in magnificent style, but no one drinks more than eleven cupfuls, each time using a different golden cup. (Strabo, Geography, 16.4.26, quoted in John F. Healey, The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus, p. 27)

Nabatean culture was also trampled by military influences and foreign rule, and by almost blind admiration for all things Roman. The Nabateans and Romans joined forces, and when the Jews of Jerusalem rebelled in 67, a thousand Nabatean horsemen and five thousand foot soldiers helped crush the revolt. The peace treaty with Rome lasted until the death of Nabatean king Rabbel II in 106, when Roman emperor Trajan seized the opportunity to conquer his erstwhile ally’s territory, annexing it as Arabia Petraea.

Meanwhile, the Roman Empire had been busy connecting maritime trade routes around the ancient world, making international commerce cheaper and often faster. The resulting upsurge in goods moved by sea had crippled the Nabateans’ economy, rendering most of their khans along the Incense Route obsolete. A nomadic way of life, already partially abandoned, now became impossible, and the desert lords settled in the communities that had sprung up around their network of trading posts, turning them into permanent settlements. Most of the population was by now either farmers or craftsmen, and only a small minority worked as traders.

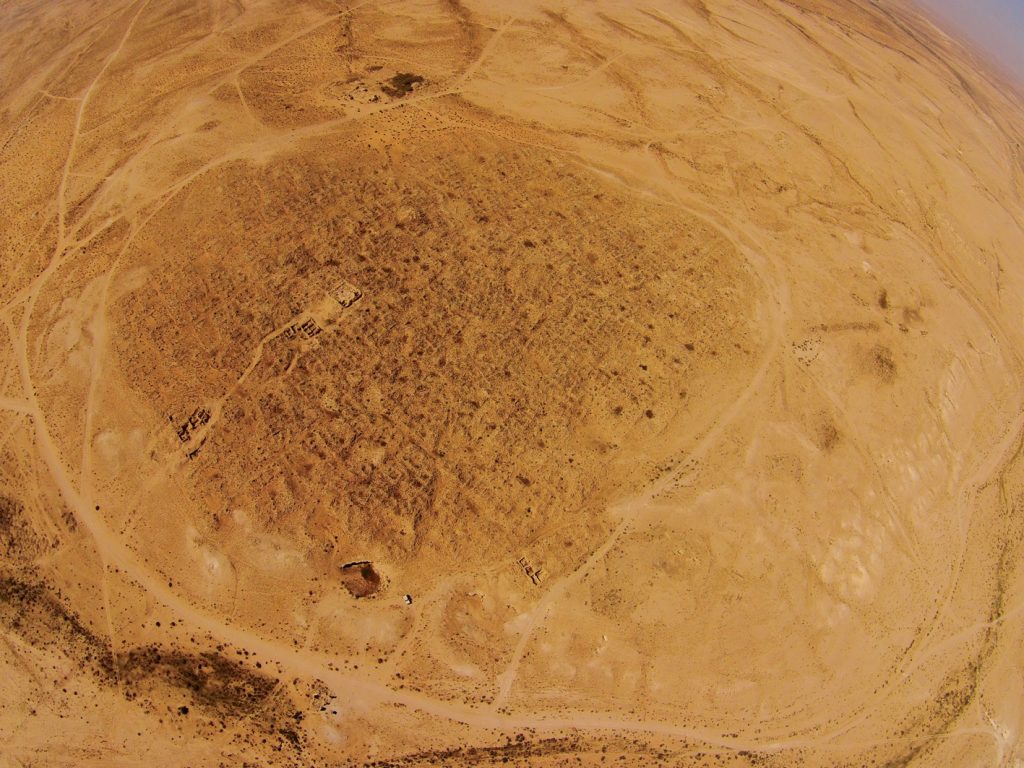

By the end of the Roman period, there were seven Nabatean towns in Judea: Avdat, Mamshit, Halutza, Nitzana, Shivta, Moa, and Rehovot in the Negev. Excavations show that Nabatean cities looked exactly like Roman ones, right down to the architecture. Temples to Roman gods graced the city square, and Nabatean customs disappeared. In the fourth century, when the Roman Empire accepted Christianity, the Nabatean temples became churches.

As Christianity spread among the Nabateans, churches, monasteries, and baptismal fonts sprang up in their settlements. Byzantine church in Avdat

Though it seemed nothing was left of their spiritual heritage, the Nabateans held on to the secrets of desert subsistence and horticulture throughout the Byzantine period, garnering every drop of water and growing almost every kind of crop in order to support the burgeoning population of their isolated settlements. The wine they produced in the arid Negev was famous for its taste and quality, and Europeans couldn’t believe such fabulous vintages were grown in the barren wilderness.

Many centuries later, the Nabateans’ success in making the desert bloom inspired the prestate Jewish pioneers of the Negev. In a novel about the early days of modern Jewish settlement, Kibbutz Revivim founders Yonat and Alexander Sand describe their protagonist’s first encounter with the ruins of the Nabatean town of Shivta:

Churches. One, two, three…. A mosaic floor, a baptismal font carved into the rock, frescoes, inscriptions, a sundial…. Immense thought had gone into optimizing the road gradients for water drainage. Channels dug alongside the houses led to cisterns and polygonal pools in the city’s center. Menashke ran from one courtyard to another, from one cistern to the next … a hundred, a hundred twenty courtyards, more, many more, three churches … thousands of people, children, schools, a huge multitude. Here they’d walked, on this street, chatting, joking, and laughing…. People had lived in the Negev, tens of thousands of them. (Yonat and Alexander Sand, Land without Shadows [Ha-kibbutz Ha-me’uhad, 1977], pp. 108–9 [Hebrew])

In the Shadow of the Crescent

The seventh-century Arab conquest of the Holy Land was the beginning of the end. It severed the Nabateans’ commercial ties with the Byzantine Empire and Constantinople, and delegitimized the tribal nation’s Christian faith. The Nabateans’ grape-based economy suffered from their new rulers’ abstinence from wine, and heavy taxes were imposed on all non-believers. Under these burdens, the lords of the desert lost the motivation to survive in their harsh native climate. Nabatean cities were abandoned and fell into decay, and their population dispersed all over the country. Many adopted Islam and assimilated among the land’s new inhabitants, putting an end to thirteen hundred years of a unique civilization.

The fascinating culture of the Nabateans, known to posterity only through outside observers, was no more. The complete history of this great people – its heritage and the secrets of its successful desert agriculture – will probably remain a mystery forever.

Natural vistas complement human artistry. Petra, view from the path leading to the Byzantine monastery