A Determined Infant

So then ’twas one designe of ye true systeme of ye first institution of ye true religion to propose to mankind by ye frame of ye ancient Temples, the study of the frame of the world as the true Temple of ye living great God they worshipped. And thence it was that ye Priests anciently were above other men well skilled in ye knowledge of ye true frame of Nature and accounted it a great part of their Theology. (Yahuda Manuscript 41 f. 7r, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem)

No mystic penned this passage; at least few would think him one. Nor was its author a prophet or priest, despite his veneration of the Temple. The writer? None other than Sir Isaac Newton, discoverer of the laws of gravity, mass, and motion. How does this quote fit our conception of the rational scientist analyzing the fall of an apple on his head? Was there more to Newton than meets the eye?

Isaac Newton was born in Woolsthorpe, in the English county of Lincolnshire, on December 24, 1642. His father had just died, and this last child of his was born premature, so tiny and weak that his mother didn’t believe he’d survive his first snowy night and left him to die quietly in the attic. Yet the baby screamed and cried so lustily that she relented, clasping him to her bosom for warmth. This child, she realized, fragile as he might look, was blessed with a great will to live. He might just make it.

Local legend had it that an orphan born on Christmas Eve was holy and destined for greatness. No such promise was evident in Newton’s early childhood, however. His mother remarried when he was three, and his stepfather, a local vicar, had no affection for the boy, so he was sent to his grandparents. The dislike seems to have been mutual, extending to his three younger half-brothers. He doesn’t seem to have gotten on particularly well with his grandparents either.

Newton’s mother brought him home at age eleven after she was widowed again. Sullen and solitary, he never grew close to the woman who’d twice abandoned him. She hoped that at fifteen, after three years at Kings School in nearby Grantham, her eldest would manage the family farm. But Newton’s efforts, if he made any, were a dismal failure, and his mother finally let him return to his beloved books. In 1661, at age nineteen, he entered Trinity College, Cambridge. He remained there for the next thirty-five years.

At first Newton supported himself by working for other students and lending money. After completing his first degree, he began teaching at Cambridge. The undergraduate curriculum was based on Euclidean geometry and Aristotle’s Ethics, but Newton was much more interested in the “New Science” of his day. He read extensively, immersing himself in the revolutionary concepts that were overturning “natural law” and geocentrism. Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes, Hobbes, and Boyle occupied Newton far more than his courses, although he found teachers (and later friends) in Cambridge alchemists Isaac Barrow and Henry More.

In 1665, a plague struck Cambridge and the university was closed. Newton continued his education at home in Woolsthorpe, where he delved ever deeper into mathematics and optics. He nearly blinded himself experimenting with light, began formulating what would later be called calculus, and – according to his own recollection – was once roused from contemplation beneath a tree by an apple falling on his head. Before the end of 1666, at age twenty-four, Newton had already developed the resulting eureka moment into a basic theory of gravity.

photo: He-hama

photo: He-hamaWoolsthorpe Manor, where Newton spent his early years.

Unchristian Arguments

Instead of rushing to publish, Newton kept his discoveries largely to himself. Resuming his studies at Cambridge, he delivered lectures (not so well-attended, it’s said), equipped a shed for alchemy experiments, and built the first reflecting telescope.

Newton did share some of his more radical mathematical theories with Prof. Barrow, on condition that none be published. Realizing Newton’s brilliance, Barrow recommended his protégé to succeed him as Lucasian professor of mathematics when he was appointed chaplain to King Charles II.

Newton’s new appointment tested his character and convictions. To attain the post, he had to affirm the Trinity, a central tenet of the Anglican faith. But he believed in only one God, immutable and indivisible, and deemed the doctrine of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit a corruption of Christianity. Unwilling to swear falsely, Newton prepared to give up the professorship. At the last moment, Barrow persuaded King Charles to modify the university charter, allowing Newton to be “sworn in” as a professor without actually taking the oath. His religious views remained private until he died, recorded only in his notebooks.

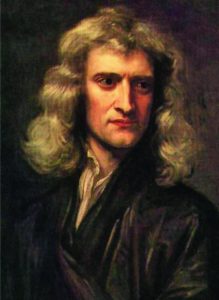

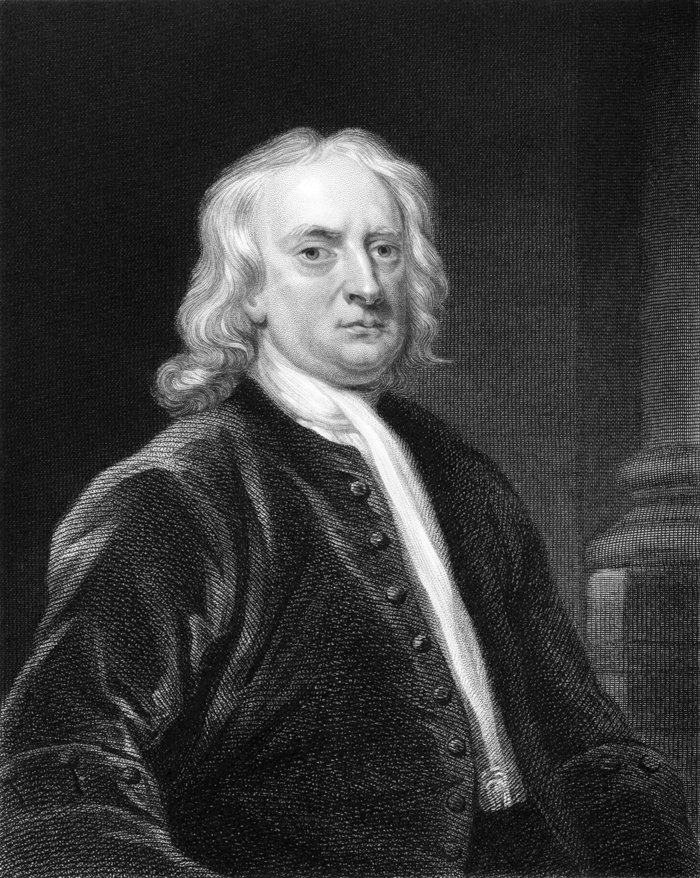

Famous portrait of the young Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller, oil on canvas, 1689

Famous portrait of the young Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller, oil on canvas, 1689

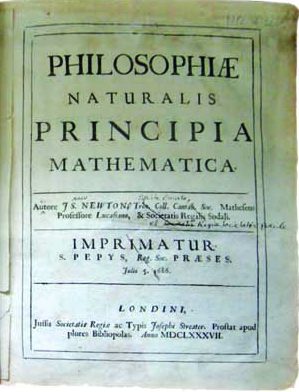

In the 1670s, Newton concentrated on mechanics and gravity but continued experimenting with optics. In 1686 he published his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, including his famous three laws of motion as well as important discoveries concerning the speed of sound, the structure of the earth, and the paths of comets. This work was written in Latin, the scholars’ language of his day.

The Principia made Newton famous internationally. Yet he remained highly involved in mathematics, developing infinitesimal calculus, although as usual he withheld publication. As a result, this method appeared only after German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz’s ideas on the subject. Newton became embroiled in a fruitless argument as to who had been first, much as he’d clashed many years earlier with Robert Hooke of the Royal Society about his optical theories.

Ten years after the Principia was published, much to his friends’ and acquaintances’ surprise, Newton turned his back on academia and accepted a government job. He moved to London in 1696 to become a warden of the Royal Mint, and was appointed master of the mint at the end of 1699. For the last thirty years of his life, he struggled to eliminate the corruption there, revamping the mint’s operations and battling counterfeiters. Newton amassed a fortune, though opinion is divided as to how he weathered the South Sea Bubble, one of the first stock-market disasters.

When Hooke died in 1703, Newton replaced him as president of the Royal Society. Already sixty-one, Newton nevertheless found the energy to turn what had been an obscure scholarly organization into a focus of popular scientific interest. His own fame helped, especially after his Optics appeared in 1704. Queen Anne made him a knight of the garter in 1705, transforming him into Sir Isaac Newton.

Priests and Planets

Well-versed in the intricacies of Christian theology, Newton was equally proficient in the Bible and even kabbalistic texts such as the Zohar. He firmly believed that his discoveries in physics and optics had merely scratched the surface of an ancient body of knowledge. God had revealed His deepest secrets through the Bible, he maintained, encoding the wisdom of creation in the measurements of the Tabernacle and the Temple, the sacrificial ritual, and the duties of the priests and Levites.

Newton’s many notebooks dealing with prophecy and the Temple abound with such references. Some are cryptic, but overall these texts suggest that the ancient priests understood the laws of the universe, particularly the solar system. These men knew the mathematical relationships between the movements of the planets and the gravitational laws governing their paths. Ancient fire rituals reflected knowledge of the heavenly system, as did the dimensions of monumental structures from Stonehenge to the Israelite Temple. What brought the great scientist to such startling conclusions?

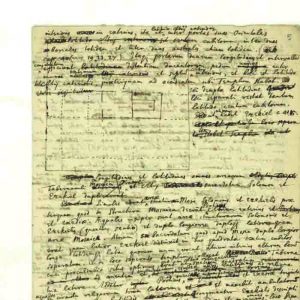

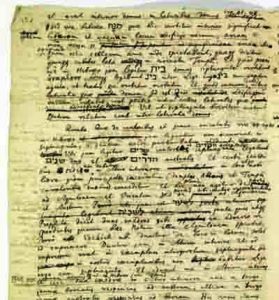

Page from Newton’s still unpublished theology notes, showing a diagram of the Temple

Newton had always been fascinated by alchemy, the study of how base metals such as lead and iron might be turned to gold. His secret experiments in this area sought to determine the rules, both physical and spiritual, governing matter’s transformation. He believed that if an alchemist were so utterly moral that his consciousness aligned with God’s will, he could also change the state of matter. Alchemy was the science of the spirit, as pure as it was true, imparted by God first to Noah, then to a tiny elite of upright and wise individuals throughout the generations.

Newton’s book on this subject, The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms, was published two years after his death. This work defines the Bible as the most reliable of all ancient documents, because it was written by God’s people, the Israelites. Newton used parallel historical sources to authenticate the Bible and compared ancient descriptions of planetary movements with the astronomical charts of his day.

According to Newton, the rulers of old – particularly the pharaohs – consistently exaggerated their power, the size of their kingdoms, and the length of their reigns. Cross-checking wars and other historical events against his own astronomical calculations, he cut history down to size.

The authors of the Bible were, Newton believed, more accurate historians. Moses, Joshua, Ezra, and the rest could be trusted because of their superior moral stature. As the Israelites diverged from the true religion and sank into idolatry, their historical accounts, too, veered from the truth. Dates such as the reigns recorded in the books of Kings and Chronicles were consequently less dependable.

As a result of these investigations, Newton concluded that the stories of the Bible predated the events recorded in Greek and Egyptian tradition. The Israelite kingdom was the first great civilization, and others copied its culture and literature. It was unique not only because of its monotheism, but because God had bestowed upon it the wisdom of art and science, which King Solomon shared with all the other nations at his kingdom’s zenith.

As mentioned, among the divine secrets disclosed to Noah were scientific principles by which matter can be manipulated. Noah incorporated these powerful precepts into rituals of fire and sacrifice. Priests encircling the sacrificial pyre at prescribed distances were mimicking the planets’ orbits around the sun. The very gravitational formula Newton had discovered was, he stated, already encoded in these rituals. Far from disproving God’s existence or intervention, these laws were part and parcel of the first religious truths He revealed to man.

Rebooting the Universe

This first religion, Newton wrote, was founded on two principles: love and fear of God, and love of one’s fellow man. Science went hand in hand with faith, forming one coherent corpus of knowledge. But while everyone was grounded in the central ideas and rituals of religion, the truths of science were largely hidden, lest they fall into the wrong hands. This is, of course, exactly what happened to the descendants of Noah.

Despite humanity’s common founding beliefs, the mighty civilizations that soon developed became increasingly materialistic, quickly losing their spiritual innocence. The simplicity with which the secrets of nature had been interlaced with religious practice was corrupted, until the original truths disappeared in a haze of superstition and misunderstanding. Eventually, the rituals begun as symbolic acts became the pillars of religion. Instead of worshipping the Maker of fire, man worshipped fire. Sun and star worship led to outright idolatry and even the deification of one’s ancestors.

Newton linked moral deterioration with a loss of intellectual subtlety, leading to further mistaken beliefs. The more man worshipped material success, the less he connected to God. Yet that connection was the key to life and blessing.

Newton felt that man’s depravity corrupted the very heavens. Therefore, God had to step in every few generations, whenever civilization grew so rotten that it teetered on the edge of collapse, endangering not just the planet, but the solar system. Sometimes this intervention took the form of natural disasters, such as the flood in Noah’s generation. Likewise, comets rebooted the solar system, shifting the planets back on track.

Other times God set the world right through its spiritual leaders, to whom He divulged further secrets of His creation. Each of these figures in turn shared part of his revelation with his fellows, nudging society forward and saving mankind from destruction. After Noah’s descendants failed to keep the world safe and good, God entrusted his creed to another family – the children of Abraham.

Alchemy apparently dates from the fifth century, combining elements of chemistry, physics, medicine, theology, and mysticism. Though today it’s considered bogus, the experimental methods developed by its devotees form the basis of modern laboratory work. The Alchemist’s Workshop, engraving by Lazarus Ercker, 1580

The Secrets of Prophecy

God selected Abraham because of his untiring search for his Creator as well as his boundless kindness. His task was more demanding than Noah’s, so he and his descendants were given access to the inner workings of creation in a purer form. Aside from the keys to the power of mind over matter, Abraham was granted a tool more potent than any other: prophecy.

Like the secrets of natural law, Newton saw prophecy as a kind of scientific wisdom to be deciphered, just as the scientist used his own observations to decode the laws controlling the phenomena around him. The results would enable him to understand – and predict – history.

In the natural world, as Newton famously pointed out, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Prophecy unmasks a similar theory of history; every deed has its consequence, good or bad. Moses personified this unified theory; greatest of all prophets, he was also the most sublime alchemist. At God’s command, he encrypted the laws of nature and the rules of history into the five books of Moses, especially the story of creation and the measurements and rituals of the Tabernacle. The simple narrative cloaks deep secrets, hidden from unworthy eyes.

As God’s partners in the covenant, graced with prophecy, the Israelites were expected to maintain a higher moral standard than the children of Noah or even Abraham, observing many more commandments. This complex code of law was intended to prevent the corruption that had plagued earlier generations. As such, Newton felt that these additional commandments weren’t an essential part of the original, true religion, the divine will.

For All the Nations

Despite all these precautions, the Children of Israel went astray over the years, much to the Creator’s disappointment. Their morals deteriorated, and they turned to idol worship, with repercussions for all of creation. After repeated warnings from a variety of prophets, the Jews’ Temple was destroyed, and they were doomed to exile. According to Newton’s theology, they ceased to be God’s chosen, and He selected a new messenger, Jesus, whose arrival had been predicted by some of the Old Testament prophets.

Newton interpreted Christianity not as a new religion, but as a renewal of the creed revealed to Noah and the Israelites. The early Christians were among the few God-fearing Jews left, and gradually converts from other nations swelled their ranks.

The era of prophecy ended with Jesus, and over the next few centuries Christianity diverged from its origins far faster than the Hebrews had. In his voluminous Treatise on Church History, Newton traced the introduction of idolatrous practices into the Church. It all started in the fourth century, he claimed, when Anastasius formulated the doctrine of the Trinity and institutionalized the priesthood. Then the Church began mediating between man and God. Newton condemned sainthood as just another form of idolatry, diverting the believer from his Creator. The scientist was certain that the power-hungry, moneygrubbing priests and prelates would be punished on Judgment Day, and didn’t hesitate to call Catholicism “the Devil’s Church.”

A true polymath, Newton had a finger in every scientific pie. Replica of the second telescope he built at Trinity College, now housed in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, Cambridge

In all his notebooks relating to prophecy, history, and science, Newton reiterated that despite Jesus’ important role in restoring the world’s spiritual order, he wasn’t God. Jesus reintroduced the original faith through Christianity, Newton explained, and was destined to return as the Messiah at the end of days, but there was only one God. He alone was the source of all life and goodness.

In due course, wrote Newton, God would punish both Jews and Christians for ignoring the message of the prophets. Retribution was built into creation: defiance of spiritual law led to suffering, just as defiance of natural law led to catastrophe. The age of prophecy might have ended, but Newton took the words of the prophets as seriously as his mathematical and physical investigations. As always, he sought provable laws of cause and effect. He even compiled a lexicon of prophetic symbols, based on mystical signs appearing across a variety of ancient cultures.

Never married, Newton divided his property among family and friends in his last years. He died in his sleep in March 1727 and was buried in Westminster Cathedral, a rare honor. His Treatise on Revelation was completed in the 1670s, but he continued revising and musing on its questions until his dying day. He was convinced that the Jews would eventually return to the Promised Land and rebuild their Temple in Jerusalem, and then the kingdom of heaven would be established on earth.

For Isaac Newton, every apparent historical fulfillment of a biblical prophecy proved God’s existence. According to Newton’s calculations, the final redemption would occur in the 21st century. Meanwhile, the Jews would begin returning to Zion in the 1800s, and a tremendous upheaval would come upon them in the 1940s. All quite extraordinary, but hardly surprising for a man who could derive the movements of the planets from an apple falling on his head.

Side by side, statues of Moses and Newton look down from the gallery of the American Library of Congress

Newton in old age, copper etching, 19th century