No Child Prodigy

Allbert Einstein was a nonconformist, a rebel, a humanist – and funny. He never boasted of his achievements, even when the press did. His disheveled exterior reflected his inner humility. As he once said:

I speak to everyone in the same way, whether he is the garbage man or the president of the university. (Fred Jerome and Rodger Taylor, Einstein on Race and Racism [Rutgers University Press, 2006], p. 39)

Einstein was born in Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg (now Germany), on March 14, 1879. His father, Hermann, was a salesman, and his mother, Pauline, an accomplished pianist. Mrs. Einstein was eager for Albert to study violin, though he showed little enthusiasm at first. In 1880, Hermann Einstein’s business in Ulm collapsed, and the family moved to Munich, where he opened an electrical equipment factory with his brother Jacob. Albert’s only sibling, Maria (known as Maja), was born in Munich in 1881.

The young Einstein was slow to develop, and his parents feared he’d never talk. He began speaking only at age three.

When Albert was five, the Einsteins hired a private tutor for him. The boy threw temper tantrums so severe that his face changed color and he completely lost control. He once even hurled a chair at a teacher, scaring her away permanently.

In 1885, with the closest Jewish school too far away and too expensive, the Einsteins sent seven-year-old Albert to a Catholic institution. In 1889, he transferred to the Luitpold Gymnasium. Impatient with its emphasis on humanities, Einstein rebelled against all authority, and his teachers responded in kind. One instructor even considered Albert’s very presence in class disrespectful, while his Latin teacher declared that he would never amount to anything.

-

-Einstein aged 14 in 1894

A Jewish medical student named Max Talmud was the first to spark the child’s interest. A frequent guest in the Einsteins’ home, Talmud supplied young Albert with popular books on science, technology, mathematics, and philosophy.

Hermann Einstein failed in Munich as well, and the family relocated to Italy, where he and his brother opened a new company. Albert stayed behind in Munich to complete his studies, but he was so frustrated and bored at school that he ran away to his parents’ home in Pavia at age sixteen, with no high school diploma.

In autumn of 1895, Einstein traveled to Zurich to take the entrance exams for the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH). Though his mathematics and physics scores were high, he failed every other test. Physics professor Heinrich Friedrich Weber noted Einstein’s proficiency and suggested he sit in on his lectures, but dean Albin Herzog insisted that the young man first complete his secondary education. After a year at a school in Aarau, outside Zurich, Albert passed the institute’s entrance exams. The liberal educational atmosphere in Switzerland, in stark contrast to the rigid discipline he’d been used to in Germany, played a crucial part in Einstein’s decision to settle in Switzerland.

The young Einstein made little or no impression on his physics instructors

Lazy Student

Aiming to teach mathematical physics, Einstein enrolled in a teaching certificate program at ETH. His instructors included professors Adolf Hurwitz and Hermann Minkowski, the latter of whom pronounced Einstein a “lazy dog … never bothered about mathematics at all” (Carl Seelig, Albert Einstein: A Documentary Biography [Staples Press, 1956], p. 28).

Prof. Weber was impressed by Einstein’s intelligence but not by his diligence.

“You have one fault,” Weber scolded him. “No one can tell you anything!” (Banesh Hoffmann and Helen Dukas, Albert Einstein: Creator and Rebel [New American Library, 1973], p. 32).

Einstein was a freethinker, outspoken, tactless, and disdainful of authority, and many professors kept their distance. He had little respect for Weber, a traditionalist in whose hands science seemed to lose all luster. By the time Albert earned his diploma, Weber despised him.

Swiss-French Prof. Jean Pernet, who taught experimental physics at the institute, also had problems with Einstein. His failure to attend class infuriated the professor, who gave him the lowest grade possible. In June 1899, Einstein’s hand was severely injured in an explosion in Pernet’s lab. Eventually, Pernet told his wayward student,

“There’s no lack of eagerness and goodwill in your work, only a lack of capability.” The professor added that Einstein obviously had no idea how difficult physics was and should try medicine, law, or philology instead. “I feel I have a talent, Herr Professor,” Einstein answered. “Why shouldn’t I at least try with physics?” Prof. Pernet ended the conversation abruptly: “You can do what you like, young man. I only wanted to warn you in your own interests” (Seelig, pp. 40–41).

Classmate Marcel Grossmann shared his lecture notes with Einstein. The latter recalled:

He abounded in the very gifts I lacked: [he was] a quick learner and ordered in every sense. Not only did he attend all eligible courses in our stead, he also wrote [notes] so neatly…. In preparation for the exams he lent me these notebooks, which for me were a lifesaver; what would have become of me without them, I would rather not write or speculate. (Albert Einstein, “Autobiographische Skizze,” in Carl Seelig, Helle Zeit – Dunkle Zeit. In memoriam Albert Einstein [1956])

The only woman in the class was Mileva Marić of Serbia, who became Einstein’s girlfriend and later his wife. The two had a daughter, Lieserl, most likely early in 1902, before they married, while Alfred was struggling to find employment and Mileva had gone home to her parents. Although the birth is documented, the child’s fate remains unknown. She may have died of scarlet fever or been adopted.

Genius at Work

In July 1900, ETH awarded Einstein a diploma and a certificate to teach mathematics and physics, but with his record – and Weber’s hostility – an assistant teaching position there was not an option. To make matters worse, Einstein’s aunt in Genoa cancelled the monthly stipend she’d been giving him as a student, and he desperately needed work so he and Mileva could marry.

Einstein applied for various jobs around Europe but was rejected. His lack of income was an even greater concern because his application for Swiss citizenship requested proof of employment. Einstein’s mind might have been full of innovative ideas about the essence of light and the electrodynamics of bodies in motion, later to become known as the theory of relativity, but his attempts to find work were a dismal failure. He was constantly changing jobs, living from hand to mouth. Suspecting that Prof. Weber was responsible for his rejection by every academic institute he applied to, he wrote to Grossmann:

I could have found [a job] long ago had Weber not played a dishonest game with me. All the same, I leave no stone unturned and do not give up my sense of humor…. God created the donkey and gave him a thick hide…. (John Stachel et al., eds., The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 1: 1879–1902, doc. 100)

Finally, in February 1901, Einstein was granted Swiss citizenship. His new nationality helped him find work as a temporary teaching assistant at the Winterthur Technical School and in Schaffhausen (both in northern Switzerland) in 1901–2.

That November, Einstein submitted a doctoral dissertation to Prof. Alfred Kleiner of the University of Zurich. The paper was rejected in February 1902, probably due to its harsh criticism of Ludwig Boltzmann’s theory of gases, although Einstein’s work also lacked experimental verification.

Grossmann and his father intervened on Einstein’s behalf and convinced family friend Friedrich Haller, director of the Swiss Federal Office for Intellectual Property, to offer him a job. Einstein was hired by the patent office in Bern as a temporary level-three technical expert, earning a meager 3,500 Swiss francs a year.

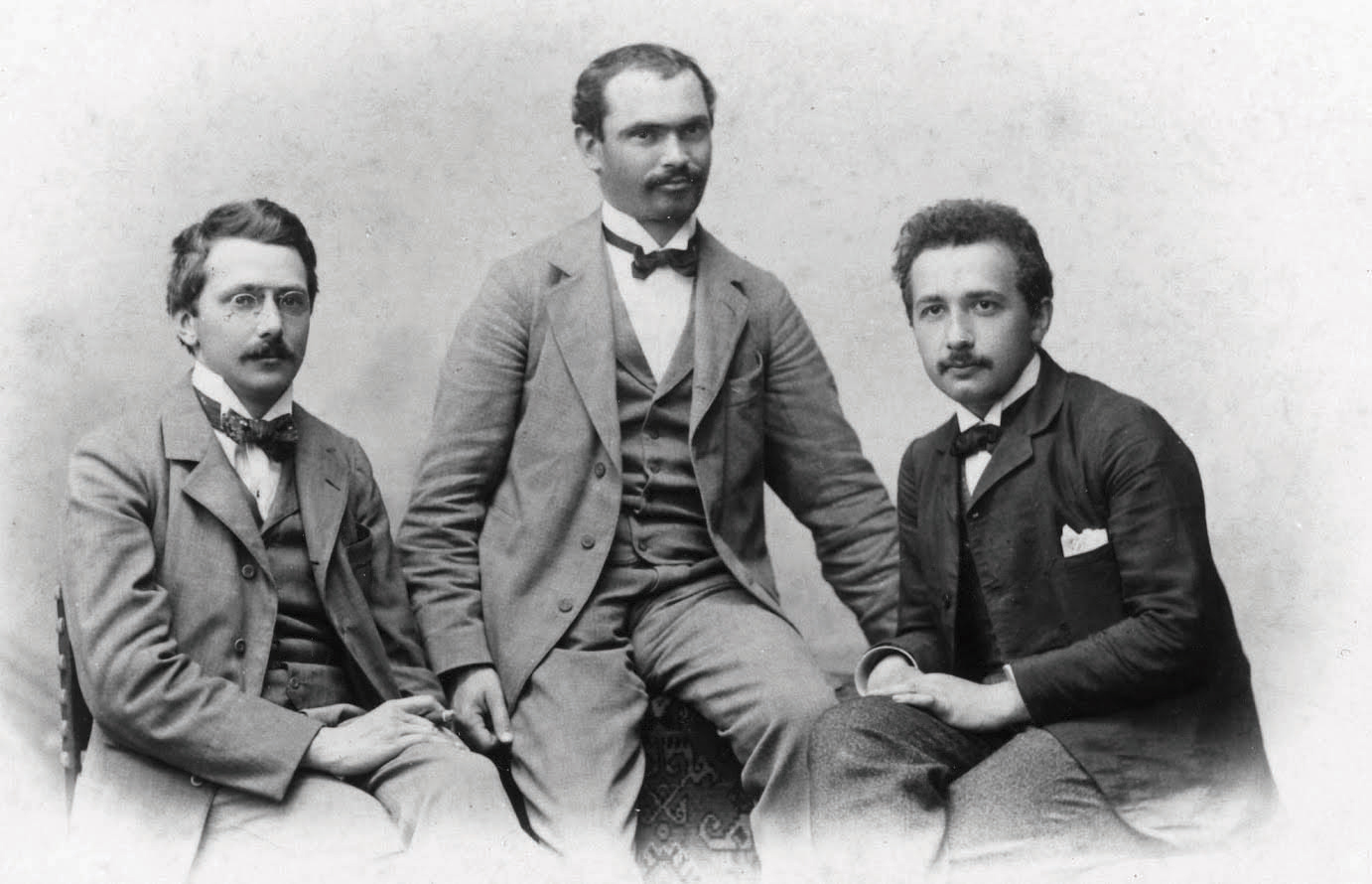

Seeking employment until his job began that summer, Einstein tutored mathematics and physics. One of his first pupils was Maurice Solovine, a Romanian student who found his university lectures inadequate, particularly in physics. An immediate rapport developed between the two, and their tutoring sessions were soon replaced by friendly philosophical debates. Doctoral student Conrad Habicht joined their circle, which they jokingly called the Olympia Academy. Though their correspondence was sometimes obscene, their studies were much more than a diversion. The philosophical reading program these scholars created was deadly serious, discussed at regular meetings rotating among their apartments.

Einstein married Mileva Marić at the registry office in Bern in January 1903. Einstein’s father had suffered a fatal heart attack in late 1902, and on his deathbed he’d apparently given this union his blessing. Einstein’s mother, however, was disappointed by her son’s choice of a non-Jewish, limping, and not especially attractive bride three years his senior; Mileva’s family likewise chose not to attend the ceremony. Habicht and Solovine were the witnesses, and after a short celebration, the young couple returned to Einstein’s apartment only to discover that he had (as usual) forgotten the key.

The couple’s eldest son, Hans Albert, was born in 1904, followed by Eduard (known as Tedel) in 1910. Hans became an engineer, later emigrating to the United States. Eduard was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age twenty; his mother cared for him until her death, and he died in an institution.

Fellow physicists in an ultimately failed relationship. Einstein with his first wife, Mileva Marić, circa 1900

Albert and Mileva Einstein with their first legitimate child, Hans. Though Einstein later claimed Mileva poisoned her sons against him after the couple’s separation, he eventually built a stable relationship with Hans, who became a professor of engineering and emigrated, like his father, to the U.S.

The Miracle Year

In a letter to Habicht, Einstein wrote that his eight hours of work at the patent office left him eight hours a day (plus Sundays) for “fooling around.” Even at work, he jotted down ideas on slips of paper, stuffing them into a drawer whenever his boss approached. Thus Einstein developed the sensational theories he published in 1905 – his “miracle year” and a turning point in scientific history.

Einstein submitted four revolutionary articles to the German Annalen der Physik scientific journal that year: on quanta of light (the photoelectric effect), Brownian motion, special relativity, and matter-energy equivalence, E=mc2. Einstein signed his paper on relativity “Bern, June 1905.” Many physicists sought out the author at the University of Bern. No one thought to look for him at the patent office.

Once again, Einstein submitted a doctoral dissertation to Prof. Kleiner, this time choosing a less radical thesis. He received his Ph.D. on January 15, 1906, but still couldn’t secure even a temporary lecturer’s position at the University of Bern. His application included his seventeen published articles, including the one on relativity. The essay was reviewed by Prof. Aimé Foster, a conservative, mediocre scientist who claimed he couldn’t understand a word. Frustrated and angry, Einstein decided to look for a job as a schoolteacher, but his friends convinced him to submit a new article in keeping with classical physics. This paper, on radiation, finally won him a position at the university, though he continued working at the patent office.

Einstein gave his first lectures on radiation theory to an audience of four – three being his coworkers – in the winter of 1908. Only one student persevered into the summer of 1909, and the course was discontinued. That year, the University of Zurich offered Einstein his first professorship. He came into class in unkempt clothes, his pants too short, and a watch dangling from an iron chain around his neck. Yet the moment he opened his mouth, his students were smitten.

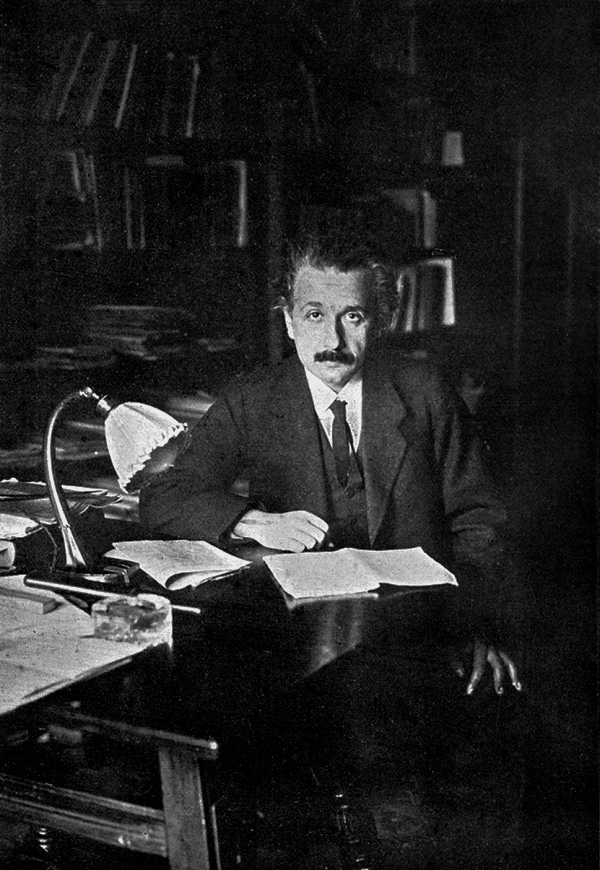

Germany was at the center of scientific development in the first decades of the 20th century. When Einstein accepted a teaching position at the University of Berlin, eight of the twelve people in the world interested in the theory of relativity were already there. Einstein in his office at the university, 1920

Birth of a Legend

Einstein had plenty in store for the world of science. Sitting at his desk in the patent office in 1907, he imagined an experiment involving a person falling from a rooftop – an idea that led to the general theory of relativity. He developed the theory over the next eight years, initially publishing research that contained incorrect equations. He worked night and day to revise them. “I am often so engrossed in my work that I forget to eat lunch,” he wrote to his son Hans (R. Schulmann et al., eds., The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 8: 1914–1918, doc. 134).

International acclaim arrived only in 1919, after a major experiment conducted by Arthur Eddington confirmed Einstein’s prediction that light rays were bent by the gravity of the sun. The revolutionary nature of the discovery filtered down to the popular press, but few really understood Einstein’s theories. A member of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge told Eddington that he must be one of only three people in the world who grasped the theory of relativity. Eddington replied, “On the contrary, [aside from Einstein and myself] I am wondering who the third might be!” (Jean Eisenstaedt, The Curious History of Relativity: How Einstein’s Theory of Gravity Was Lost and Found Again [Princeton University Press, 2006], p. 2). The New York Times published a similar anecdote; Einstein had apparently warned the paper’s editor that only twelve brilliant people in the entire world could comprehend his new theory. The Times published it anyway, then complained that the theory had reached a lay audience too quickly.

The story of the genius and his unintelligible hypothesis became legendary. After Einstein and Chaim Weizmann crossed the Atlantic together to raise money for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1921, Weizmann was asked on arrival in New York whether he now understood Einstein’s theory. He replied that “During the crossing, Einstein explained his theory to me every day, and by the time we arrived I was fully convinced that he really understands it” (Helen Dukas and Banesh Hoffmann, Albert Einstein, the Human Side: New Glimpses from His Archives [Princeton University Press, 1981], p. 62).

Meanwhile, Einstein had grown estranged from his wife Mileva. She’d stayed in Switzerland when he’d accepted an academic position in Berlin just before World War I, separating them permanently. The couple divorced amicably in 1919, the year he became famous. That June Einstein married his cousin Elsa, who’d cared for him when his health deteriorated after intensive revisions of the theory of relativity a few years earlier. They stayed together until her death in 1936, and Albert adopted Elsa’s two daughters from a previous marriage.

Inspired by the Violin

Einstein often compared scientific innovation to music. His best ideas occurred to him while playing the violin. He took the instrument everywhere and played at every opportunity. In 1920, Einstein was invited to lecture at the University of Prague, a city he’d loved since his professorship there in 1911. He’d spent that year honing his mathematical and physics skills and playing violin with friends for hours on end. At the honorary reception after his 1920 address, Einstein announced from the podium that he would play the violin instead of speaking. His renditions of Mozart and Bach drew tumultuous applause from an audience probably profoundly relieved to be spared further incomprehensible details of relativity theory.

Professional musicians generally avoid performing with amateurs, but even the world’s greatest violinists felt privileged to play with Einstein. He joked that they must have believed some of his fame would rub off on them. Einstein complained that all the publicity was making him stupid, noting that at least his sense of humor saved him from the stupidity of his admirers.

Janos Plesch, a physician friend of Einstein’s from Berlin, recalled that one day a woman turned up claiming to be Lieserl, Einstein’s illegitimate daughter. Plesch was somewhat surprised, but the woman convinced him; he even began to see a resemblance to Einstein in her intelligent son. Plesch and a few friends decided to help the woman. They found her a job and registered the child in school, then wrote to Einstein that he had a daughter and grandson. The famous scientist was unmoved. To evoke Einstein’s paternal emotions, Plesch even sent him two clever drawings the boy had produced. This effort only amused the genius, who begged (in rhyme) to be spared his friends’ foolishness.

Fingers to the strings, on board ship from New York to San Diego, 1900. Einstein formed musical friendships wherever he went, often playing with other scientists. He claimed he owed some of his best ideas to the inspiration of his violin

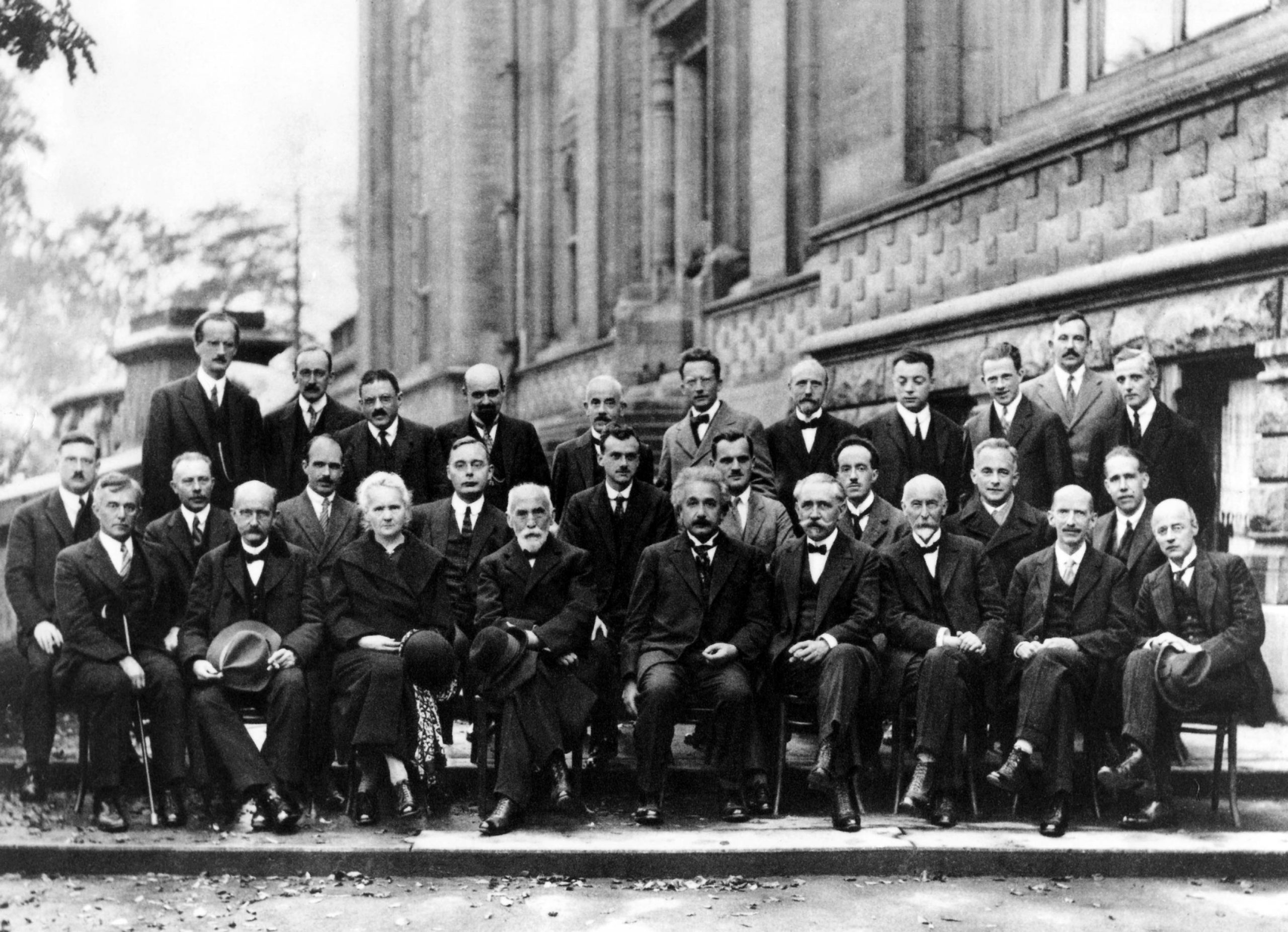

Einstein and colleagues at the 1927 Solvay Conference in Brussels on quantum mechanics, an extraordinary gathering of such famous physicists as M. Planck, Marie Curie, H. A. Lorentz, Niels Bohr, Erwin Shroedinger, W. Pauli, and W. Heisenberg

No Dice

Einstein immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1930s, joining the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey. By now a renowned physicist, he’d been awarded a Nobel Prize in 1922 for his work on the photoelectric effect (conservative members of the Nobel committee had not yet accepted his relativity theory). As promised prior to his divorce, he sent the prize money to Mileva.

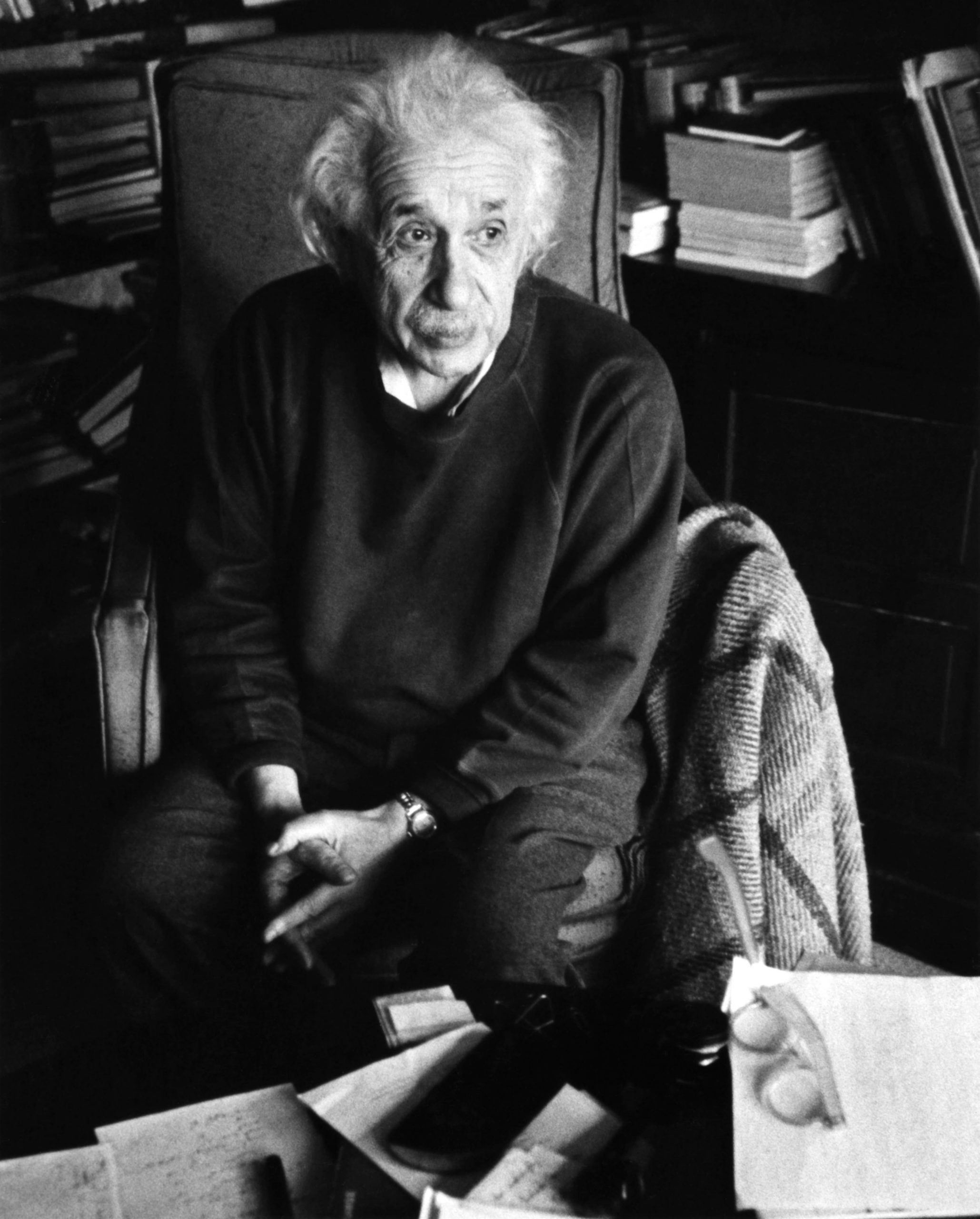

At the IAS, while his theories inspired other physicists to delve into quantum mechanics and its implications, Einstein continued his lonely search for a unified field theory that could explain both gravity and electromagnetism. This quest occupied him until his death on April 18, 1955. He was known to withdraw into his office, close the drapes, and scribble equations for hours on end. Sitting with colleagues, he’d often switch to his native German in order to think more clearly. When even this tactic failed, he would pace, run his fingers through his mane of white hair, and announce in his best English, “Now I will a little tink.”

As Einstein grew older, he continued to assert that quantum theory had to be incomplete because of its random nature and the degree of uncertainty it assumed. A firm believer in determinism and causation, he argued that the full theory had yet to be discovered. Many physicists insisted that the theory should stand as it was, but Einstein famously countered, “God doesn’t play dice with the universe.”

When Weizmann, the first president of the State of Israel, passed away in 1952, a Jerusalem daily suggested that Einstein replace him. David Ben-Gurion encouraged the notion, and Abba Eban, the Israeli ambassador to the U.S., was instructed to officially propose the position to Einstein. The idea first reached him by way of a short New York Times article a week after Weizmann’s death. Convinced the piece was a joke, Einstein laughed it off until journalists began pestering him. Several hours later, Eban’s telegram arrived. Einstein never seriously considered the offer. Although he favored coexistence between Arabs and Jews in Israel, he felt that as president, he would face endless conflicts of conscience.

Einstein believed Arabs and Jews could live together in the Holy Land, but as a pacifist, he objected to any military or political entity there. Nationalism scared him, hardly surprisingly considering his familiarity with pre-Nazi and Nazi Germany. He was a proud Jew but didn’t believe in a chosen people. Profoundly secular, he was a citizen of the world, with Swiss and American citizenship.

Yet Zionism drew him. Though Einstein initially rejected the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, the miserable state of the East European Jews arriving in Berlin in the aftermath of World War I and the anti-Semitic pogroms they’d experienced convinced him otherwise. He began supporting Zionist efforts, but cautioned against the extreme, irrational nationalism practiced elsewhere in the world.

So Einstein told Eban he couldn’t be president of “our State of Israel.” Ben-Gurion was relieved, having decided it was a terrible idea. Two days after sending the telegram, Eban met Einstein at a reception in New York. The ambassador was glad to have put the entire chapter behind him, especially when he saw that Einstein had arrived in full formal dress – but, as usual, without socks.

Einstein was very public about his Zionism, although it never became practical. With Ben-Gurion at Princeton, May 13, 1951

Einstein spent his last two decades at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), in Princeton, New Jersey. The institute relieved him of teaching duties and allowed him to devote himself to research. Einstein in his IAS office, 1955

A beautiful mind. Einstein’s genius made him not only a legend, but also a research subject. In this experiment he was asked to think about the theory of relativity while electrodes recorded his brain waves

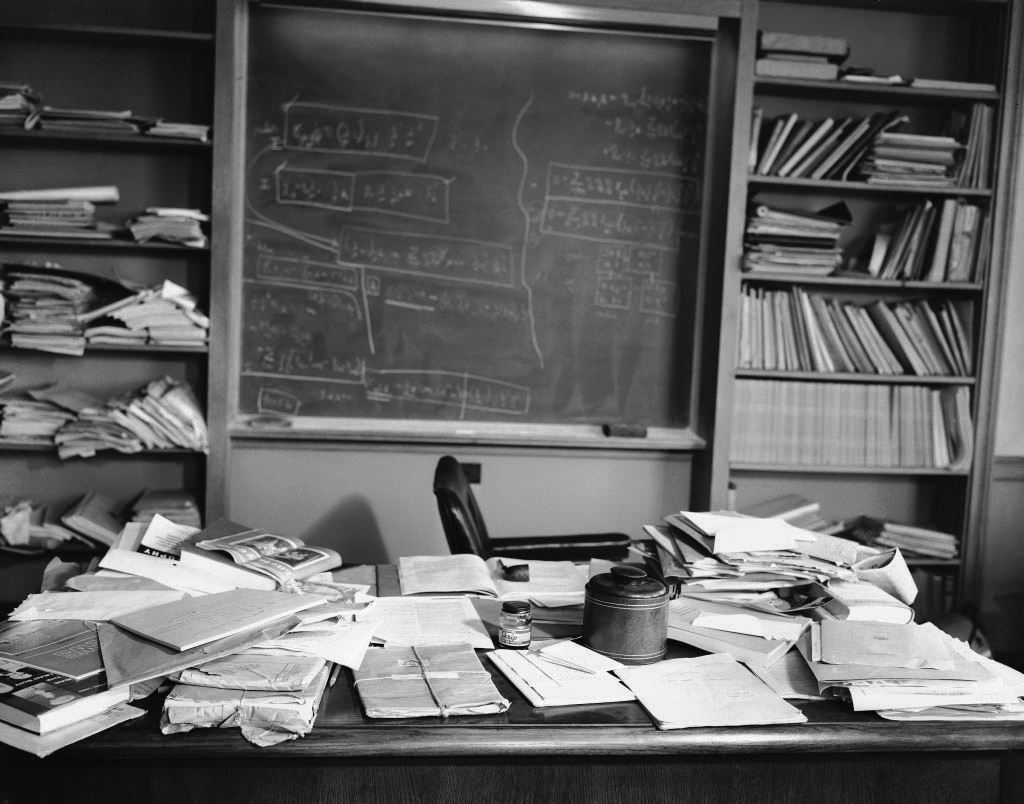

What was he working on? Einstein’s office in Princeton has been preserved just as he left it, with formulas still on the blackboard, books and papers strewn across his desk, and his pipe lying among them

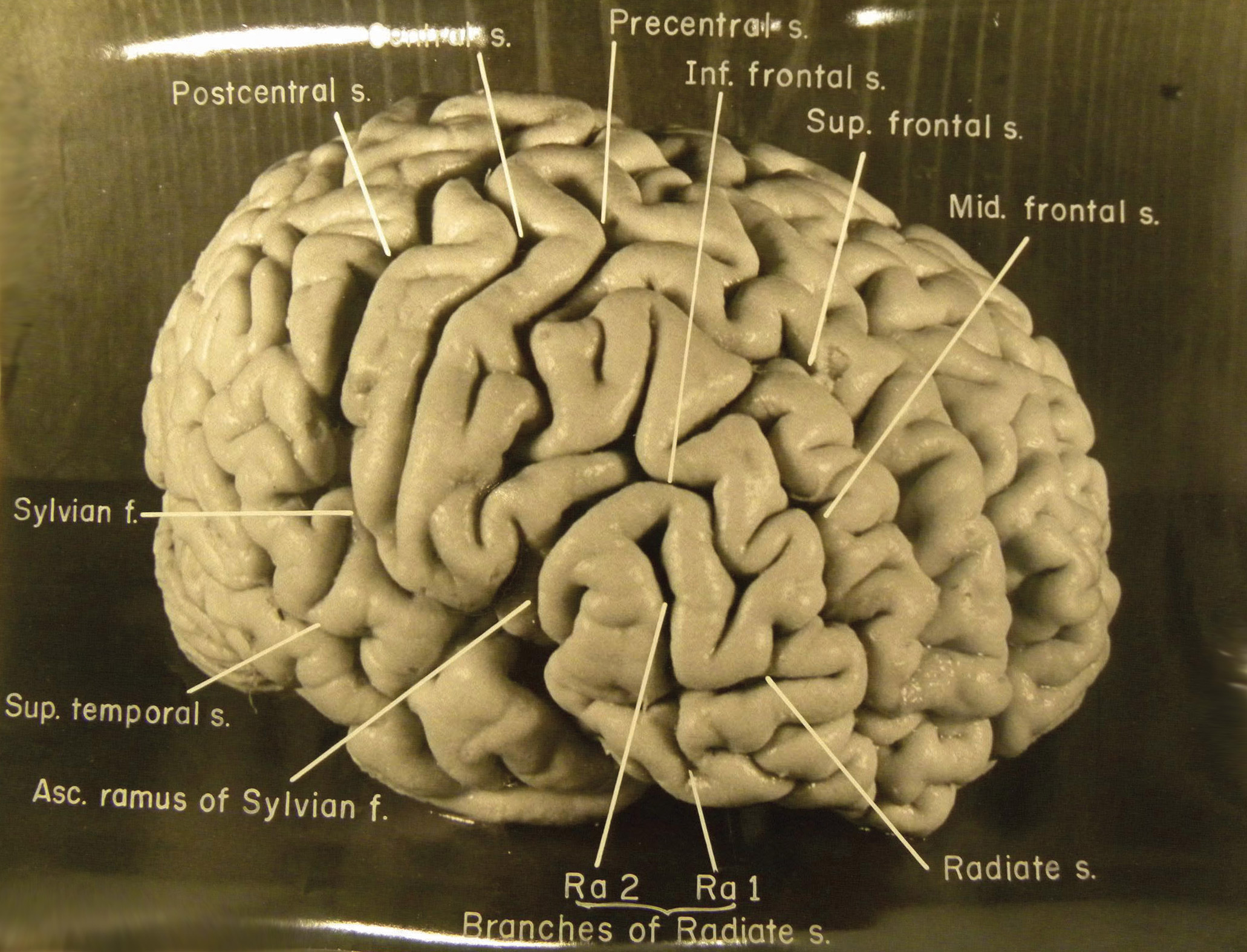

As an avowed atheist, and to avoid idolization, Einstein stipulated in his will that his body be cremated and his ashes scattered into a New Jersey river. But pathologist Thomas Harvey preserved the great scientist’s brain and eyes, later providing slices of brain tissue for neurological research. Einstein’s brain

Further reading:

Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe (Simon & Schuster, 2007); Dennis Overbye, Einstein in Love: A Scientific Romance (Penguin Books, 2001); Albert Einstein, Ideas and Opinions (New York: Random House, 1954); Alice Calaprice, The Quotable Einstein (Princeton University Press, 1996).