Jim Crow

Before the advent of mass media, when movies and television were still unimaginable, vaudeville was the most widespread public entertainment, especially for middle- and working-class whites in the U.S. Traveling shows featured dance routines and skits as well as magicians, jugglers, comics, miracle workers, preachers, and even cripples displaying their twisted limbs.

Racial differences were always good material for comedy, so minstrel revues included music and slapstick based on black stereotypes.

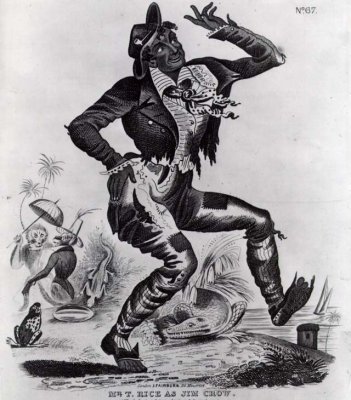

It all started in the early 1830s when actor Thomas Dartmouth (“Daddy”) Rice’s gullible, dark-skinned Jim Crow character became a vaudeville fixture. The name became the black equivalent of John Doe, even figuring in the racial segregation legislation enacted at the end of the 19th century. Other caricatures followed, such as Sambo, Big Mamma, and Miss Lucy Long. All quickly pervaded American culture, then spread worldwide.

Alien Culture

Though these characters were black, the actors playing them were generally white, darkening their faces with stage paint to create an effect known as blackface. In segregated American society, especially in the South, the minstrels trod a fine line between mocking black life and exposing the abuses of slavery.

Were the white artists who aped black music or appearances enamored with an exotic multiculturalism or ruthlessly exploiting another race? Before-and-after “blackface” poster advertising a minstrel show

Current research suggests that performers and audiences alike were simply curious about what they perceived as an alien culture. Yet their interest was certainly tinged with suspicion and condescension. Blacks were portrayed as subservient to whites, and their supposed naivete and ignorance exploited to comic effect. Even worse, while black artists couldn’t make a living, whites were aping and exploiting blacks for their own benefit.

Nevertheless, minstrel shows popularized Afro-American music, and once black actors and musicians began appearing on stage, audiences rejected blackface in favor of the real thing.

Minstrel culture never completely disappeared. Much of it was absorbed into film, radio, pop music, and cartoons. Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, and other white performers strove for a black “feel” in their music. Dispensing with frizzy wigs and blackface, they infused rock and roll with a passion and vibe that was a more genuine, more liberal tribute to the black musical heritage than the slapstick of minstrel.