Proof You’re Married – Or Not

One might suppose that a local rabbinate’s archives, with their records of marriages, deaths, and divorce, are not the most sensational section of any community vaults. Yet they are often a rich source of genealogical material, especially in communities where the civil authorities outsourced such registration to the rabbinate. These archives can also shed much light on community life as well as halakhic precedent.

One such document is a certificate confirming that the holder is single. This form is required whenever one member of an engaged couple is from out of town and has to prove his or her marital status. When such a certificate attests to the single status of a couple, something fishy must be going on. A file containing a hundred such documents must be very fishy indeed. In fact, the story behind this file is both poignant and of national significance.

The file belonged to Abraham Leib Silberman, chief rabbi of Safed under the British Mandate. Silberman’s records include certificates issued by rabbis in eastern Europe during the 1930s, of which the following is typical:

3 Tevet 5699 [December 25, 1938]

Certification

I hereby certify that no wedding ceremony between Mr. ___ and ___ was performed under my auspices, that the records in their documents (on the travel permit) stating that they are married to one another are only for the well known reason and for official purposes, and that on the date recorded on their documents, August 17, 1937, I did nothing that would prevent their marrying anyone else in accordance with Jewish law….

In witness whereof, I affix my signature on the date noted above:

Haim Zalman Tzvi b. Rabbi Menahem Mendel Šerelis

Rabbi of the above locality

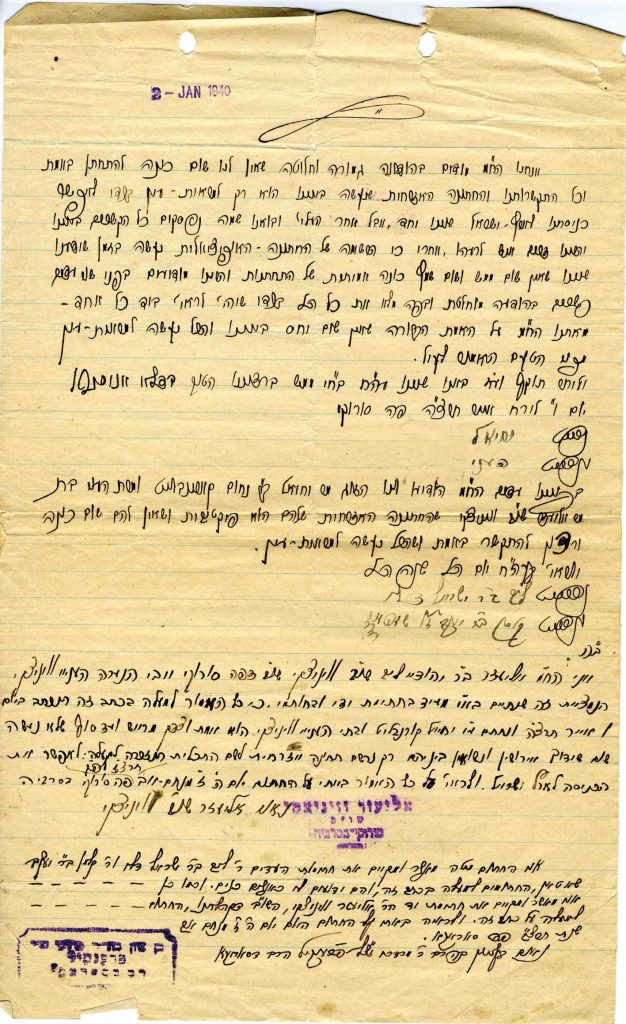

A couple’s affirmation that the civil marriage recorded between them does not reflect any intentions to wed, 1940

Issued by the rabbi of Aizpute, Latvia, the certificate states that the couple in question – whose names have been omitted here to protect their privacy – has entered into a fictitious marriage “for the well known reason.” This obscure language concealed a web of deception spun to allow young Jews to immigrate to Palestine. The British White Papers severely restricted entry into Palestine, so enormous efforts were made to maximize the few valid permits obtained. Unmarried individuals fortunate enough to receive them entered into fictitious marriages, so each permit ensured the entry of two Jews into Palestine rather than one. Bachelors visiting from Palestine did much the same, while some even traveled to Europe for this purpose.

Keeping Up Appearances

All these weddings included no halakhic ceremony whatsoever. Attached to many marriage certificates are letters from witnesses and from the officiating rabbi, indicating that the civil procedure was undertaken with no intention of entering into a formal halakhic marriage. One writ even includes a statement of husband and wife’s intent:

We the undersigned acknowledge…that we have no intention of genuinely marrying, and that the bond between us and the civil marriage we have entered into is solely for appearances, in order that we may enter Palestine together. After our aliya and arrival in Palestine, we will sever all ties between us and be as strangers….

Other certificates come with additional evidence of their fictitiousness. The He-halutz Ha-mizrahi movement gave a woman guidelines listing the basic information she had to remember regarding her “husband,” in addition to his name: his place and year of birth, and, of course, the name of her supposed mother-in-law.

Despite all the precautions, there were halakhic complications. Though civil marriages have no validity in Jewish law, some authorities insisted that these unions be terminated by a get and would therefore attach a signed writ of divorce to each marriage certificate. The women divorced thereby were then ineligible to marry a Kohen. The Chief Rabbinate in Palestine stiffened its requirements in turn, demanding rabbinical confirmation of certain individuals’ unmarried status. The resulting overseas correspondence with various European rabbinates also appears in the files of the Tel Aviv Rabbinate.

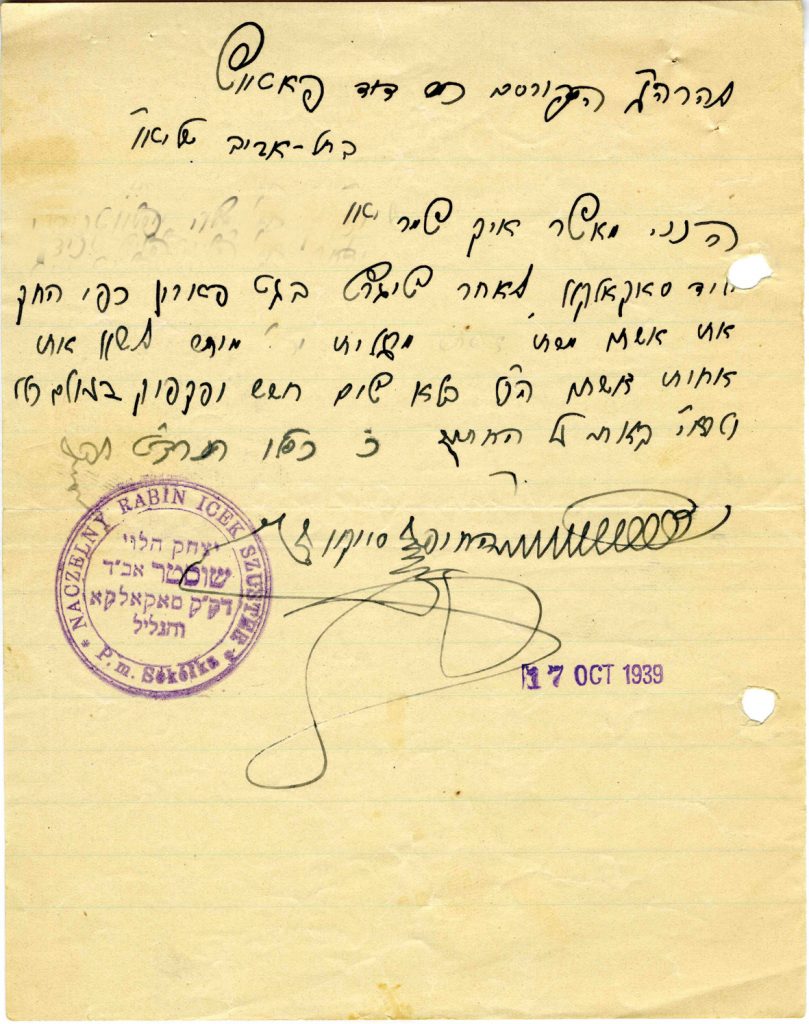

The marriage scam posed another problem for the rabbis involved: as religious functionaries providing marriage licenses on behalf of the authorities, they were not allowed to submit false information. Some rabbis therefore used ambiguous language, as in the following letter from Rabbi Icek Szuster of Sokółka, Poland:

I hereby certify that Mr. ___, born in Sokółka, after divorcing his wife, Mrs. ___, under a lawful writ of [civil] divorce, shall be allowed to marry the sister of his aforementioned wife with no concern and doubt whatsoever.

As Jewish law forbids marriage to the sister of one’s ex-wife, Rabbi Szuster was hinting that the marriage he was recording had no validity in Jewish law.

It would seem that marriages of this sort were fairly common. My wife’s grandmother, Rebbetzin Esther Wagner, told me that her father, Rabbi Shraga Feivel Willig, the last chief rabbi of Buczacz, Galicia, would arrange a fictitious marriage for any bachelor who had obtained an immigration certificate. Some couples actually hit it off and remained married, avoiding the bureaucracy involved in an additional ceremony.

These rabbinic archives, then, not only reveal a little-known way of circumventing British immigration restrictions, they add invaluably to our knowledge of East European Jewry. Often these certificates provide the only record that a given rabbi served in one shtetl or another. Many of these rabbis perished in the Holocaust, while the couples they linked lived on in Israel, together or apart.

Rabbi Isec Szuster’s letter ostensibly allowing a divorcé to marry his ex-wife’s sister, October 17, 1939