The Price of Equality

Though Jews campaigned long and hard for equality in their many countries of dispersion, the privilege proved to be a mixed blessing. In Europe, the price of emancipation was total cultural integration, exchanging Yiddish and other Jewish dialects for the national language, and involving the government in Jewish education and communal matters. The Hirschler Collection, in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, opens a fascinating window onto how Hungarian Jewry split over integration issues.

The Jewish Emancipation Law was approved in the Hungarian Parliament in 1867. Predictably, it was welcomed by Jews espousing religious reform, while traditionalists were less enthusiastic. Which of these camps prevailed?

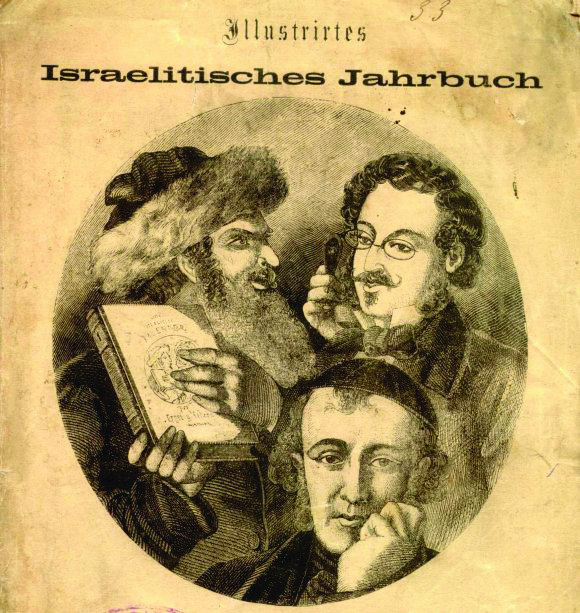

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Courtesy of WikipediaAn Hassidic, Orthodox and Neolog Jew, representatives of the three main strands of Hungarian Jewry. The cover of a Hungarian periodical from 1861, Leopold Kompert’s short-lived ‘Illustrirtes Israelitisches Jahrbuch’.

The Jewish Congress

On February 16, 1868, Hungarian minister of education and religion Baron József Eötvös called for a committee of Jewish leaders to discuss the formation of an autonomous Jewish congress that would regulate the Jewish community and represent it to the Hungarian government. Delegates were to be chosen by the community, not imposed on it from above, as in France and some German states. But since it was mostly members of the Jewish Neolog movement who responded to Eötvös’ call, these progressives dominated the committee, eclipsing the Orthodox.

As the congress wasn’t expected to debate theological questions, rabbis were at first excluded from its ranks. Furthermore, delegates had to be fluent in German or Hungarian, whereas most Orthodox Jews spoke only Yiddish and Hebrew. These measures raised a storm, after which Eötvös allowed rabbis (Neolog as well as Orthodox) to vote and be elected to the congress.

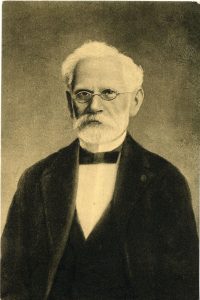

Though the baron’s intentions may have been perfectly innocent, those of his adviser, ophthalmologist Ignác Hirschler, certainly weren’t. President of the Pest (later Budapest) Neolog congregation, Hirschler was a driving force behind Jewish emancipation. He probably chose the initial committee members, seeking to minimize Orthodox influence. Hirschler’s personal archive – consisting mainly of correspondence dating from 1868 and early 1869, in German and Hungarian – contains extensive information regarding the congress and Hungary’s Neolog community. The letters, addressed to Hirschler and his colleagues in Pest, come from Jewish leaders and activists all over historic Hungary and often include copies of his replies.

Neolog vs. Orthodox

When Hirschler started working on his Central Committee of the Assembly of Notables, as the congressional steering committee was called, the Orthodox community had already organized to fight the Neologs. The Orthodox had set up the Hitőr Egylet (Guardians of the Faith), with its own newsletter, Magyar Zsidó (The Hungarian Jew), to promote its conservative viewpoint.

Much of the correspondence in Hirschler’s archive is addressed to this Central Committee, which was secretly sending letters to Neologs throughout Hungary, encouraging them to establish branches of the committee in their areas. This body also bought the Izraelita Közlöny (Jewish Bulletin) to spread its own message, countering the segregational Orthodox agenda.

In a letter sent to Károly Wottitz on April 6, 1868, Mór Mezei wrote the following on behalf of the Neolog party:

Regarding the upcoming congress, and in opposition to Orthodox agitation, we are organizing our own party. The party has a central committee and aims to establish committees in every district and significant place. … Who would you recommend in Győr who would be able to manage the duties of the committee? … Our bulletin also needs subscribers.

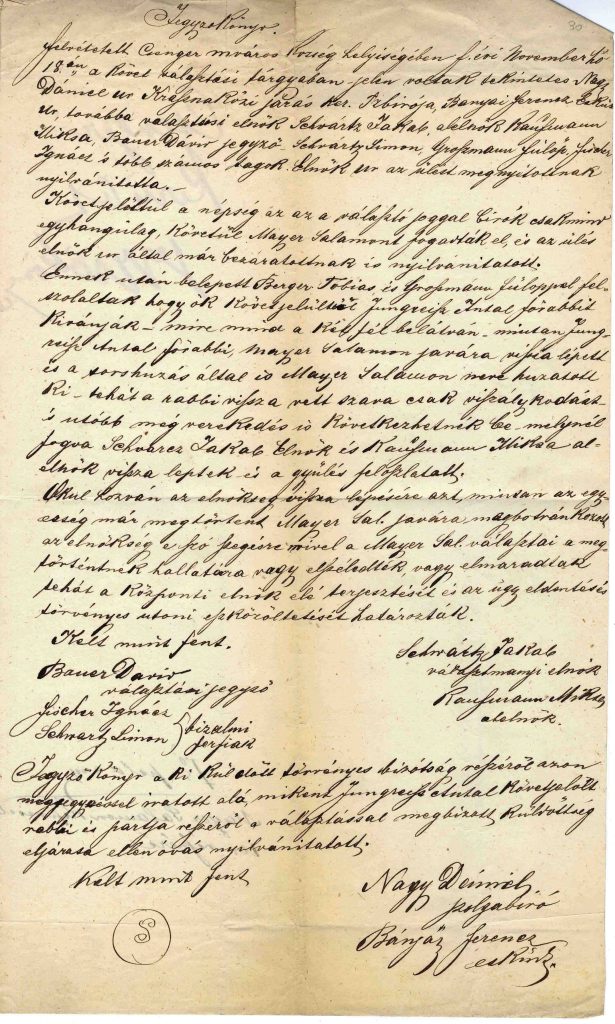

Congressional elections were held in November and December 1868. Conducted much like state elections, they were equally open to bribery. Both parties mounted massive election campaigns with protests and propaganda generating a great deal of noise and publicity. Each side accused the other of cheating, and violence broke out. A dispatch from the district of Csenger is illustrative:

Our candidate, Salamon Mayer, was elected unanimously by the electorate, and the assembly adjourned. Afterward Tobiás Berger and Fülöp Grossmann intervened, saying they wanted Rabbi Antal Jungreisz to be a delegate instead. [Another vote was held,] and in the actual results, Salamon Mayer was selected and Antal Jungreisz stood down. This [Orthodox maneuvering] could have caused great discord, easily ending in a brawl.

The Neolog leaders, many of them prominent businessmen and professionals well-connected with the election authorities, probably used their connections to influence the outcome. They weren’t above trickery either, as long as it lowered the Orthodox party’s chances. On August 25, 1868, Dr. Lajos Fischer reported to Hirschler:

In Kolozsvár our party definitely doesn’t have enough voters to elect at least one delegate out of two. … In my opinion, however, if our community persistently abstained from voting, we could prevent two delegates from being elected.

The Neologs won 57.5 percent of the vote. Yet until the congress convened, it wasn’t clear which camp certain delegates really supported. On December 17, 1868, Mór Váradi requested that Hirschler cancel the election of two of them:

Rumors have spread that delegates J. Landesberg and Löbl Frankl belonged to the progressive camp … but though Landesberg doesn’t admit it publicly, he backs the Hitőr Egylet. Moreover, Löbl Frankl heads the Hitőr Egylet in Nagyvárad. … I request the cancellation of the election.

The congress was held between December 1868 and February 1869 in Pest, with more than two hundred representatives participating. Unable to reconcile their differences, they failed to establish a national Jewish organization. Hungarian Jewry split, forming independent Neolog and Orthodox communities as well as those that sought to retain the existing unified (or “status quo”) congregations. The voice and identity of Hungarian Jews was fundamentally weakened as a result.

-

-Dispatch sent to Hirschler from the district of Csenger, complaining of potentially violent Orthodox attempts to alter the outcome of an election for council members

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (http://cahjp.huji.ac.il) rescues, restores, and preserves historical documents concerning the Jewish people from communities worldwide, from the Middle Ages to the present