Modern Jewish Identity

When asked to define modern Jewish identity, Sigmund Freud often responded with a story. A European Jew boards a train. Alone in his compartment, he immediately removes his hat and shoes, loosens his tie, suspenders, and belt, and sprawls across the benches. Suddenly the door opens, and an elegantly dressed passenger enters the car. The Jew snaps to attention and straightens his clothing. The other fellow settles himself in his seat, and the momentary embarrassment passes. Just as the Jew buttons the last of his buttons, his traveling companion asks, “Would you happen to know when Yom Kippur falls this year?” “Oy,” the Jew groans, kicking off his shoes and stretching out again.

Like many of their contemporaries, Jews in the United States at the turn of the 20th century found themselves aboard an immigrant train, destination unknown. They had turned their backs on their eastern European ports of embarkation and stuffed their traditional identities into a suitcase. They were determined to make good, to become more American than the Americans, even if their acquaintance with things American was based largely on hearsay. They straightened their ties, shaved their beards, and tried their best to look as American as possible, with no hint of Jewishness. Fair-skinned and eager to assimilate, they integrated more easily than immigrants from Italy, Puerto Rico, and the cotton fields of the American South. Appearance was a crucial asset; the “show” was the thing. Combining it with another cardinal American value – business initiative – they arrived at the concept of “show business.” With this key to the Pearly Gates of Broadway, Jewish immigrants penetrated and even shaped the very core of popular culture, leaving a legacy that Americans are still humming.

Springboard to Respectability

Jews did not invent Broadway. They neither opened New York’s first theater, just off Times Square, nor staged the first musicals. However, like the cinema and comic books – two other entertainment industries launched in the U.S. in the late 19th century and significantly upgraded by Jewish immigrants – the American musical theater owes its international fame to talented Jewish entrepreneurs.

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr., born to a German immigrant father and a mother of Polish origin, was one of the first Jews to create glitzy shows combining vaudeville with spectacular music. His Ziegfeld Follies had no plot, but their spectacular staging imbued the almost random combination of acts – ranging from operatic duet to vulgar skit – with the magic of escapism. The middle classes loved it, and they became Broadway’s most loyal audience.

Following Ziegfeld’s lead, the three Polish-born Shubert brothers identified the enormous commercial potential of the dilapidated theaters on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. They bought and refurbished them, complete with neon signs, and filled them with the finest musical and dramatic talents of the time. An aura of prestige surrounded the glitz and chintz of the theater district throughout the 1920s. The growing ranks of bourgeois Americans were eager for an avenue of cultural escapism that was truly, originally American, something that could define American culture and differentiate it from its European counterpart.

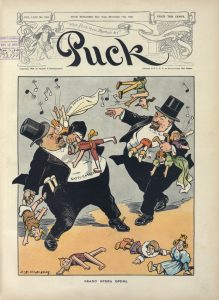

And original it was. In its formative years, Broadway distanced itself from European theatrical and musical traditions. There was no room for Strindberg’s heavy melancholy or Wagner’s operatic opuses. The stage was set and the music playing for America in all its glory. Dancers in top hats and black-faced comedians mocking freed slaves’ thick accents echoed the many voices – and tensions – making up the melting pot of America’s immigrant society. High and low, classic and avant-garde, black and white, slapstick and shmaltz – all met on the boards of the stage, often with amusing consequences. The revue fit its diverse audience like a glove, expressing the conflicted psyche of the Jewish immigrants who had created it.

For popular comedienne Fanny Brice and successful impresario and librettist Billy Rose – as for Ziegfeld, the Shuberts, and the innumerable Jewish producers, actors, and writers who made Broadway the capital of American theater – the stage became a springboard out of their impoverished immigrant neighborhoods. Onstage and off, they donned tailored suits and savored the illusion that they were no longer on the train, but had fully integrated. For these immigrants, social success took precedence over artistic self-actualization. They left that for the next generation, which would be free of their complexes and inhibitions. And indeed, in the 1920s and 1930s, these second-generation immigrants subtly redefined Broadway and its message, creating the “American songbook” along the way. Repudiating their parents’ heritage while remaining true to core Jewish values, they brought a breath of fresh air and a new social spirit to the Broadway stage.

Making Waves

Show Boat premiered on December 27, 1927, at the Ziegfeld Theater. For an audience primed for the two hours of unpretentious frivolity provided by the average revue, it must have come as something of a surprise. Directly confronting issues of racial segregation and African American repression, the show actually told a story. The eponymous pleasure cruiser steaming down the Mississippi River offers those living along its banks a heady brew of glittering musical illusion. The illusion shatters when the star of the show, light-skinned Julie, is revealed to be half-black. As such, she cannot share the stage with white actors or play to a white audience. Furthermore, her love for a white man may land her in prison. Julie must abandon both him and her career for a more tolerant environment.

As if it were not controversial enough to depict the South as a land of degenerate bigotry, the musical’s creators outdid themselves by giving a heartrending number to a black character. Jim, an impoverished laborer, crumples to the ground on the Mississippi shore and bursts into song:

You an’ me, we sweat an’ strain,

Body all achin’ an’ wracked wid pain,

Tote dat barge!

Lif’ dat bale!

Git a little drunk

An’ you lands in jail.

Ah gits weary

An’ sick of tryin’

Ah’m tired of livin’

An’ skeered of dyin’,

But ol’ man river,

He jes’ keeps rollin’ along.

“Ol’ Man River” became one of the great protest songs of the 20th century. It was utterly different from the usual Broadway ditties, jolting its listeners out of their complacency and forcing them to contemplate the racial tensions at the heart of their society. Show Boat illuminated the dark corners of American life and utilized its powerful melodies to drive its point home. This improbable hybrid of serious social statement and weightless musical entertainment proved to be a dizzying success. Audiences that would never have dreamed of attending a docudrama exposing racial discrimination packed the mezzanines to enjoy the score. Dazzled by the performance, they found themselves committed, almost despite themselves, to rethinking American society’s attitude to minorities. The creators of Show Boat knew their audience could contain the dissonance between the fabulous “show” and the wretched reality. They knew it because they had lived the disparity themselves, even though they were white.

The Ziegfield Theater in 1936. Built in 1927 at a cost of two and a half million dollars, the theater seated 1,600. The building was demolished in 1966 despite public protest

Needless to say, the makers of Show Boat were all Jewish: from Edna Ferber, who wrote the novel on which the musical was based, to lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, composer Jerome Kern, and producer Ziegfeld. They could have chosen material that was easier to stomach. Yet they disregarded the immigrant inner voice begging them not to upset their host society, and consciously set dynamite on stage. Unafraid to shine the spotlight on otherness, they led Broadway from the cultural center to the social fringe and back again. Show Boat was the first production staged with an interracial cast. They took the risk because they identified with the stakes. These Jews knew a thing or two about xenophobia, and about the futility of hiding one’s origins. Julie, exposed as “other” despite all her efforts, is a distant relative of the Jew on the train.

Show Boat’s indictment of Southern indifference to injustice along the banks of the Mississippi is rooted in the Bible’s implicit critique of those who lolled in the shade of the Nile in Egypt, complicit in the persecution of the Israelite slaves. Behind the show’s boat lurks an immigrant steamship, and the show’s themes implied that those aboard were still far from safe shores. But Broadway’s second generation of Jews had stopped concealing their identity, and were busy making room on stage for other “others” as well.

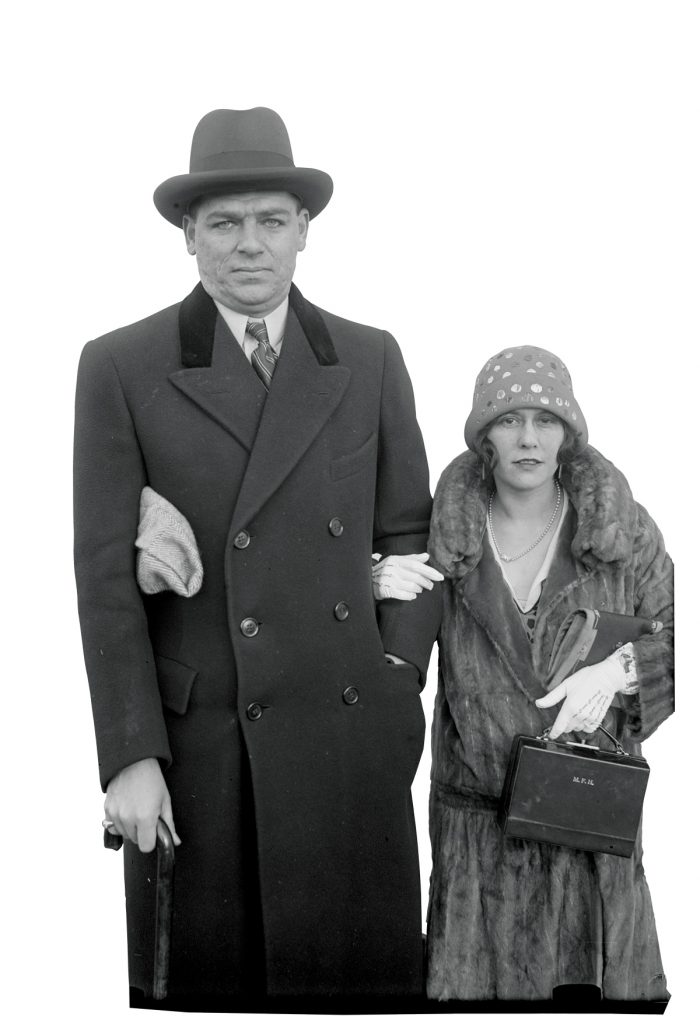

His mother may have been a Scottish Episcopalian, but Oscar Hammerstein II was a third-generation Jewish impresario. His grandfather, Oscar Hammerstein I, originally a cigar maker from Germany, built theaters and opera houses after his arrival in America. Hammerstein II with his wife

Pushing the Boundaries

Show Boat paved the way for other Jewish productions combining razzle-dazzle packaging with controversial content. In 1935, the brothers George and Ira Gershwin unveiled Porgy and Bess, a black opera that once again brought the Manhattan crowd face to face with the inhumanity on the fringes of American society. Pal Joey, a 1940 musical by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, centered on an amoral, second-rate jokester willing to sacrifice his soul on the altar of American capitalism.

Richard Rodgers, Irving Berlin, and Oscar Hammerstein II watch hopefuls audition on the stage of the St. James Theater, New York, 1948

After Hart’s tragic death, Hammerstein joined Rodgers to create the most outstanding creative partnership in Broadway history. Their first collaboration, Oklahoma! (1943), dealt with a familiar theme: wandering heroes seeking a home. Alongside Curly, the American cowboy who lands himself a spouse as well as a homestead, the musical features two immigrants looking for their own piece of the heartland. Rodgers and Hammerstein chose Joseph Buloff, star of New York’s Yiddish theater, to play the itinerant peddler. The hint is subtle but unmistakable: American society is built on the principle that land is available for anyone prepared to work to develop it, but by that same principle, immigrants must do everything possible not to betray the trust of the masters of that land, adopting the values of their new home and becoming loyal American citizens.

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s subsequent musicals also revolved around foreignness and integration. South Pacific (1949) bluntly assesses the prospects of a romance that defies racial, religious, and national boundaries. The King and I (1951) examines the clash between Orient and Occident and the likelihood that an English nanny can fit into the Siamese royal court. And The Sound of Music (1959) focuses on a fledgling nun ill-suited to the convent, and the family she joins, which finds itself no longer welcome in its own homeland.

As children of German immigrants, the two artists were well aware of the precarious nature of their circumstances and how easily patriotism could edge toward xenophobia. Broadway was an ideal place for them to surreptitiously examine their Jewish identity, allowing them to reflect on their place in American society while celebrating family and community values. It was not by chance that the final scenes of The Sound of Music – their last collaboration before Hammerstein’s death in 1960 – showed the von Trapp family fleeing from the Nazis into the unknown. We would like to think that America would give them a home, but who knows?

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s famous musical The Sound of Music, adapted from the true story of the von Trapp family, was also one of the most successful films in history. Playbill from the 1959 Broadway production

Production Values

Rodgers, Hammerstein, Kern, Hart, and Gershwin were by no means the only Jews active on Broadway. With the support of Rodgers and Hammerstein, Tin Pan Alley veteran Irving Berlin scored with Annie Get Your Gun (1946), whose heroine rockets from the rejected fringes of American society to the pulsating heart of the country’s entertainment industry. The show includes a hit with which every Jewish artist on Broadway would agree: “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

The musicals of Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner – My Fair Lady (1956), Gigi (1958), and Camelot (1960) – similarly interweave social commentary with great music in their exploration of inappropriate matches. And the heroes of Frank Loesser’s Guys and Dolls (1950) and How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying (1961) melodiously undermined both the Protestant work ethic and the prudish family values of middle-class America.

Leonard Bernstein, the wunderkind of the concert halls, reached Broadway in the 1950s. Bernstein teamed up with Stephen Sondheim and Arthur Laurents to produce West Side Story (1957), another work that probes the failure of the American melting pot.

Leonard Bernstein at a rehearsal for West Side Story in 1957. Carol Lawrence (who played Maria) is leaning on the piano to his left, and lyricist Stephen Sondheim is at the piano

The train that had delivered Jewish immigrants from the Old World to the New stopped at Broadway indefinitely. Old-time Klezmer musicians found their virtuoso talents in singular demand. The winning combination of highly singable hit songs and the “show” of show business allowed its passengers – producers, songwriters, and performers – to reflect collectively on the landscape waiting beyond the station platform. They drenched their plays in Jewish irony and equally Jewish optimism. Casting themselves as Americans while playing to a heavily immigrant audience, they nevertheless occasionally allowed themselves to loosen their belts and give themselves away with a heartfelt “oy vey.” Although they knew where they had come from, they did not always know where the road would lead them, and they preferred to swish and shimmy their way into the unknown to the merry tune of a Broadway melody. n

Further reading:

Stewart F. Lane, Jews on Broadway: An Historical Survey of Performers, Playwrights, Composers, Lyricists and Producers (McFarland, 2011).