The Great 19th Century

Egyptian history has certainly had its glory, but it seems almost ironic that Egyptians should term the period from the late 18th century until World War I “The Great 19th Century.” Yet although this was exactly when Europe’s colonial ambitions began to solidify in Egypt, it was also a time of intensive national development, from which the modern Egyptian state emerged. These years ushered in a new era for Egypt’s Jewish community as well, granting it an unprecedented sense of security culminating in full-scale integration into a newly secular Egyptian society.

The centralized government introduced by Ottoman governor Muhammad Ali Pasha in the1820s brought a measure of law and order to Egypt and its Jews. Carefully consolidating his power after Napoleon’s brief conquest and withdrawal from Egypt, Muhammad Ali disposed of all opposition and installed himself as khedive, or semi-independent ruler, in 1805. He embarked, with moderate success, on a nationalization program intended to fund the modernization of Egyptian society. The first communal board of Jewish representatives was founded in Alexandria in 1840 (the year of the blood libel known as the Damascus Affair), and by 1861 Egypt had an estimated twenty thousand Jews.

Instability followed Muhammad Pasha’s death, but in 1863 his grandson, Ismail Pasha, succeeded him. Modernization speeded up under Ismail, who ruled until 1879. The Suez Canal was dedicated in 1869 to international acclaim, putting Egypt squarely on the map. With its gates now wide open to western investment, Egypt encouraged education and professional training among its citizens. Jews began playing a significant part in public life as well as in the economy; European arrivals also added to the community.

Then Ismail resigned under the weight of Egypt’s national debt and amid pressure from European creditors. Rioting broke out, developing into the ’Urabi Revolt (led by officer Ahmed ’Urabi) and the dawn of Egyptian nationalism.

The revolt was crushed by the British conquest of Egypt in 1882, but nationalist fervor continued seething below the surface. At the beginning of the 20th century, Egypt was ostensibly independent but remained a British protectorate until 1922. Relatively few Jews played a role in Egypt’s political and national awakening, and the most outstanding was without a doubt Yaqub James Sanua.

.

Biting Satire

Yaqub son of Raphael Sanua was born in Cairo in 1839. French educational influence later resulted in his acquiring the name James, and it’s as James Sanu that he’s famous in Egypt. His mother too was Egyptian-born, but his father immigrated from Italy. Rafael Sanua was a trusted adviser to Prince Ahmed Pasha Yaken, another powerfully placed grandson of Muhammad Ali Pasha. Impressed with the boy’s intelligence and abilities, knowledge of languages, and familiarity with Jewish Scripture, the Quran, and Arabic poetry, Prince Ahmed paid for his education in Livorno, Italy.

Arriving in 1852 in Livorno, Yaqub studied art history, music, drawing, and languages, and staying in Italy for four years. He soon became enamored of the theater. The young man was also influenced by the rise of Italian nationalism during this period and witnessed the swift modernization of European cities.

Shortly after Yaqub’s return to Egypt, both his father and his patron Prince Yaken died, forcing him to forge his own path. At first he turned his proficiency in Arabic, Hebrew, Italian, French, English, German, Spanish, Greek, and Russian to his advantage, working as a teacher. But he never abandoned his love for the theater.

In 1869, Cairo’s French Comedy Theater opened in the Al-Azwaheya Gardens, followed by the Egyptian opera house. Both were built by Ismail Pasha to host the foreign troupes he invited to entertain his guests at the dedication of the Suez Canal.

Since none of these groups performed in Arabic, James Sanua resolved to launch his own theater company, believing that Egypt deserved its own culture, just as it was entitled to determine its own fate. Sanua began appearing with his players in a large coffeehouse by the opera house.

Ismail Pasha opened Egypt up to western influences, but instead of being grateful, the European powers forced him to abdicate

Only four months later, James was invited to perform at Ismail Pasha’s palace. Sanua staged three plays there, all in Arabic: Modern Girl, Two Wives for One Man, and Egypt’s Coquette. All three comedies included a moral and, between the lines, social criticism. Ismail Pasha was delighted, declaring to all his senior aides and ministers that Sanua had founded Egypt’s national theater company. The governor promptly dubbed the playwright “Egypt’s Molière.” The comparison was apt. Not only was Molière (1622–1673) patronized by Louis XIV of France, with his actors known as “the King’s Company,” but his plays combined wit, biting satire, and social commentary.

Sanua saw himself first and foremost as an Egyptian; his Jewishness was secondary. As Egypt’s intellectuals began envisioning national independence, he shared their dreams. His theater was part of the nationalist struggle. He wrote his plays in colloquial Egyptian Arabic, incorporated Egyptian music, and drew on his intimate knowledge of Egyptian mores and culture. Plays of and for the people – that’s what gave Sanua’s productions their authenticity and mass appeal. Nevertheless, his work was both Oriental and Occidental, blending European culture with Egyptian earthiness.

Operetta for the Masses

As Sanua’s audiences grew, he shifted from comedy to social satire, dealing with the daily grind, corruption, and similarly corrosive national issues. Criticizing arranged marriages and other traditions, and even the royal family and Ismail Pasha himself, the popular playwright was playing a dangerous game.

James usually directed his own plays, often acted in them, and even composed some of their music. Every performance began or ended with him alone on stage, explaining his message, just as Molière would address his audiences, thanking them for coming and answering their questions.

Scholars have noted other similarities between Sanua and Molière: the tendency to unravel plot complexities in a sudden, swift, dramatic denouement; a preference for happy endings, as in all good comedies; and a focus on the problems of ordinary life – in the hope of presenting solutions.

Even after a play had been through a number of performances, Sanua would tinker with the script, either in response to audiences’ requests or just to keep people guessing. Stock characters included the Nubian, with his southern Egyptian accent; the Syrian, speaking his own dialect; and the sheikh, whose classical literary Arabic was so flowery as to be almost unintelligible. Actresses, too, joined his company – a first in Egypt’s traditional society.

Sanua was a poet as well, ending his plays with a few verses summing up the plot. In his more complicated works, every act concluded with a sonnet. Two Wives, for example, ended thus, lest his condemnation of the all too common practice of bigamy be missed:

Add, if you want a bitter life,

To your children’s mother another wife.

One who seeks a life of hope

Won’t bead women on a rope.

Sanua was equally uncompromising when criticizing authority. In the end, he overstepped his boundaries, and in 1872, in response to his satire Homeland and Liberty, Ismail Pasha closed him down. James tried a new avenue, founding two scientific societies to promote modernization and nationalism, but they were soon banned as well, and Sanua fled to France.

The Guy with the Glasses

Back in Egypt two years later, James picked up where he’d left off. He joined the nationalists whose anti-establishment efforts culminated in the unsuccessful ’Urabi Revolt, and the Egyptian army officers who led it were among his close friends. Sheikh Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, a modernist Islamic theologian and thinker, and his disciple, Muhammad Abduh, were also part of Sanua’s inner circle. Climbing swiftly up the political ladder, he soon put exile behind him.

Perhaps no Jew did more to shape the society and culture of modern Egypt, and with it the Arab world. Despite rumors that James converted to Islam, Arabic scholar Shmuel Moreh has both documentation and oral testimony from Sanua’s daughter proving that the playwright and activist remained a Jew until his dying day.

In 1877, Yaqub founded Abou Naddara (The Man with the Glasses), the first satirical journal in the Arab world, the first to include caricatures, and the first written in popular as opposed to literary Arabic. Abou Naddara criticized Ismail Pasha’s rule mercilessly, especially his “addiction” to the west and the corruption within the palace walls. In addition, the journal derided primitive Egyptian customs and highlighted social ills and injustices. By the time Sanua had published fifteen issues over the course of a year, Abou Naddara was shut down, and he was back in exile.

This time, however, instead of despairing, the intrepid journalist kept publishing from France. Copies of the journal were smuggled into Egypt and distributed both there and in other Arab countries, where they fanned the flames of pan-Arab and Egyptian nationalism. Abou Naddara even got to India, stirring nationalist feeling among Muslims there.

When the ’Urabi Revolt broke out, Sanua felt compelled to return to Egypt. Once the uprising failed, giving the British an excuse to take control, he was exiled yet again, this time for good. Yet he continued the Egyptian national struggle. The slogan Massr lele-Massrein – Egypt for the Egyptians – was his invention and quickly became synonymous with the fight for independence. Sanua lectured widely from his home base in Paris, decrying the injustice of Britain’s conquest of his homeland.

James published numerous newspapers and periodicals over the years, using them first to attack Ismail Pasha for his westernism, then to attack British colonial rule. He called on the other Great Powers – particularly Turkey and France – to rein in the British, expel them from Egypt, and appoint a native Egyptian king in their place. Sanua was also the first to expose the evils of British colonial rule in Sudan.

He published in eight languages, though mainly in French or Arabic. James edited all his publications and wrote much of their content. They were widely appreciated for their humor and biting satire as well as for their cutting-edge journalism, featuring photos and color when both were relatively new, especially in the Arab press.

Sanua died in Paris in 1912, still dreaming of Egyptian nationalism. Egypt won partial independence only in 1922, and full self-rule had to wait until 1952, when Abdel Nasser replaced the monarchy.

True Pioneer

Yaqub Sanua typified the Egyptian Jews of his day, who loved their country, integrated into society, and left their mark in various fields, including economics, politics, and culture. Yet he stands out as the only Jew expelled from Egypt for supporting the nationalist cause.

A certain Egyptian scholar is currently attempting to “debunk” the legacy of James Sanua, since the only records of his activities are those he wrote himself. The modern Egyptian theater was founded by others, this expert claims. But all his colleagues, in Egypt and elsewhere, disagree. For them, Sanua remains the undisputed pioneer of the Egyptian stage.

Multi-faceted Media

To the modern eye, Abou Naddara’s caricatures and cover pages seem unsophisticated. Yet they provide a glimpse of his radical ideology as well as highlighting the hot topics in the early days of popular Arab journalism

Personalized Journalism

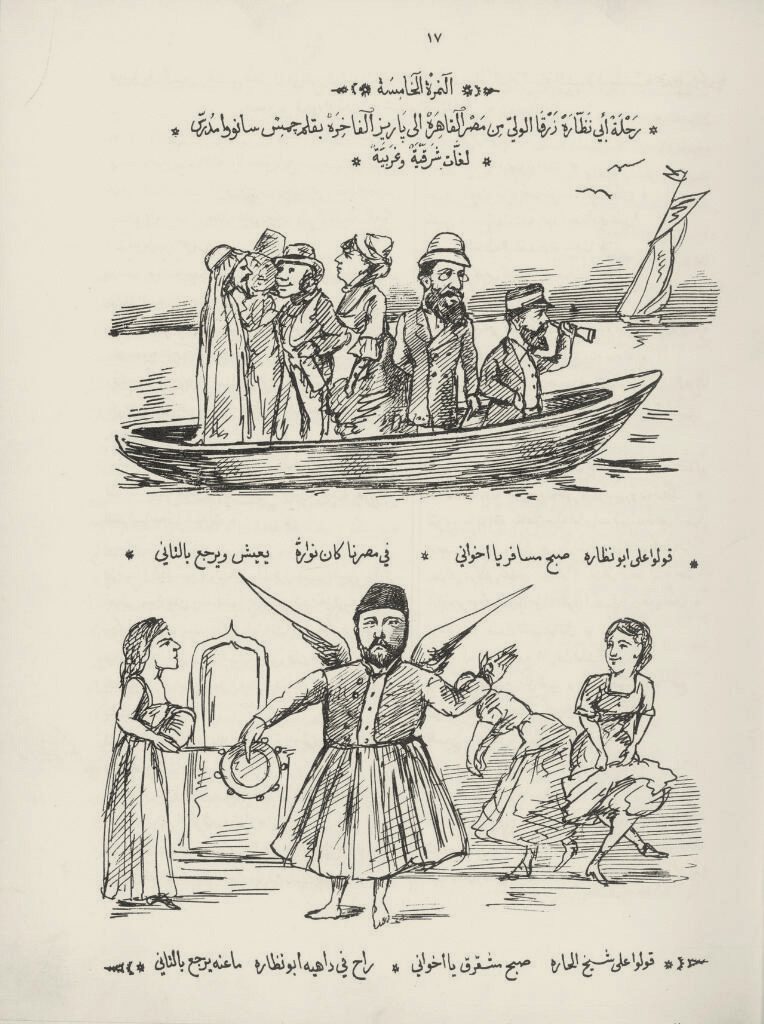

Even the name and emblem of Sanua’s paper were inseparable from him. This caricature, drawn at the time of his second expulsion, expresses how insulted he felt about his treatment: “Abou Naddara is off to France, wish him well. Ismail Pasha is leaving Egypt, let him go to hell.” 1878

In the Name of the People

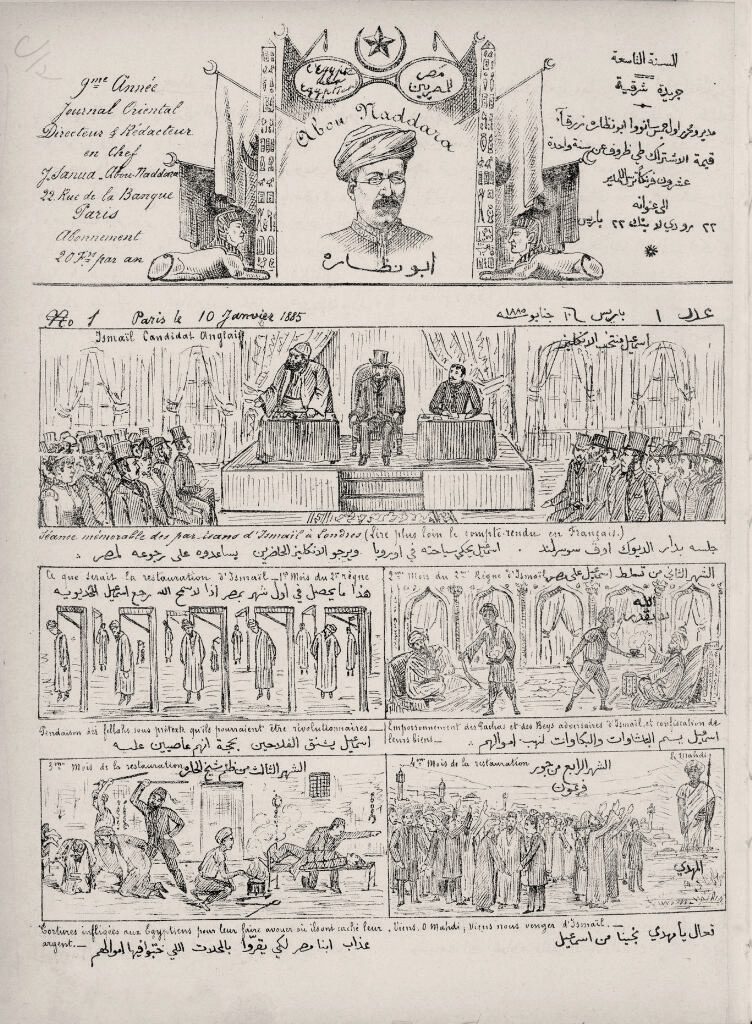

Cover page of Abou Naddara showing Ismail Pasha returning to Egypt in European dress, persecuting his country’s upper class and peasants alike and stealing their wealth. His subjects respond by praying for the salvation in the form of the Mahdi – the Islamic Messiah. January 10, 1885

Comic History

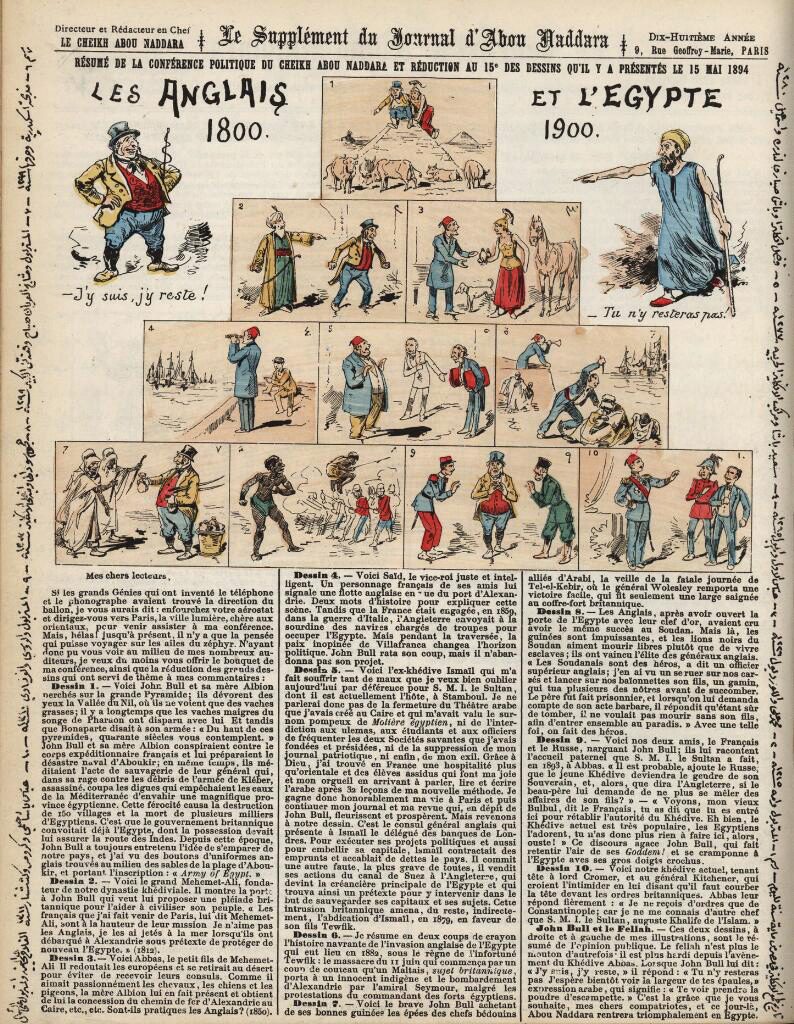

Sanua’s readers had few sources of information other than his paper.

Comics summing up a century of British involvement in Egyptian affairs, with explanations below, May 15, 1894

The Pen Is Mightier

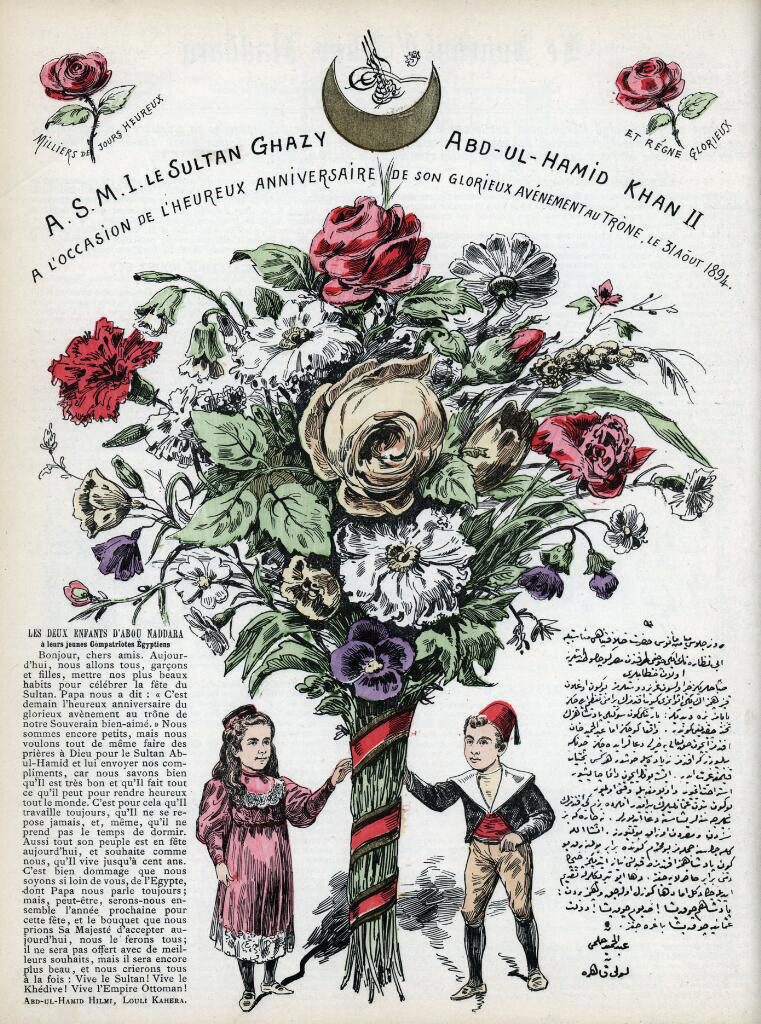

With no Egyptian tradition of freedom of the press, Sanua’s hands were tied, so he used irony instead. Excessive praise was just as effective but less actionable. To mark Abdul Hamid’s birthday, for example, Sanua wrote that the sultan was sleep-deprived as a result of working so hard for Egypt’s poor citizens. His readers got the picture. August 31, 1894

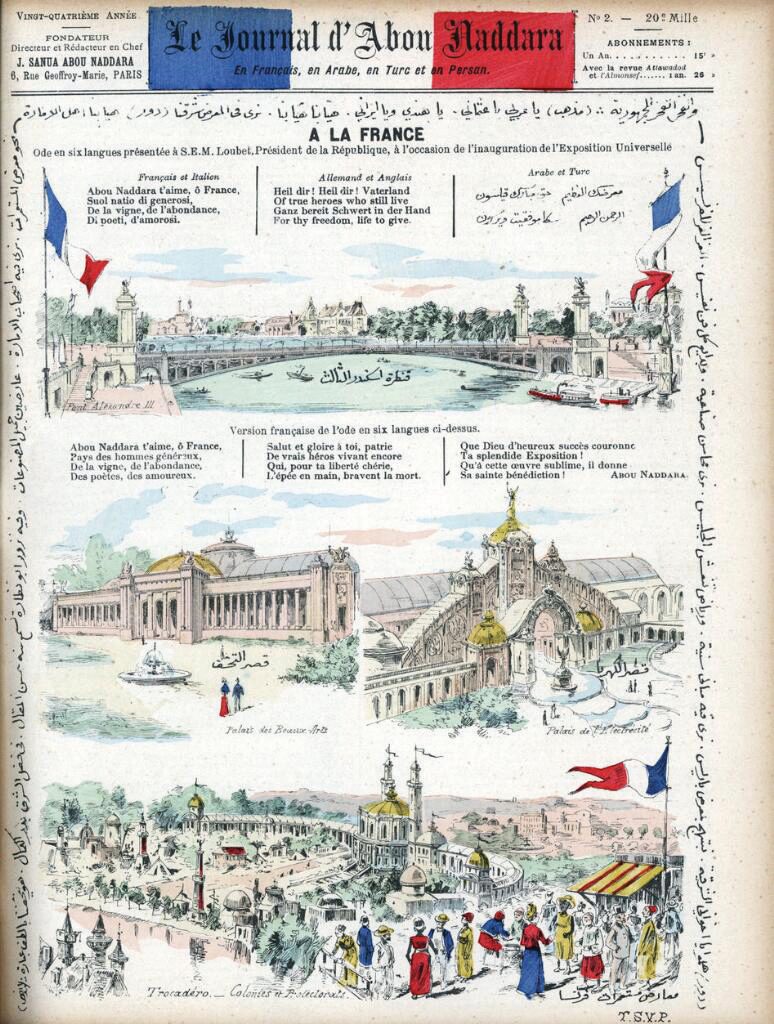

International Nationalism

A fervent believer in Egyptian independence, Sanua supported the patriotism of other nations too. To mark the Paris World Exposition of 1900, for instance, he sang France’s praises in six languages – English, French, Italian, German, Arabic, and Turkish.

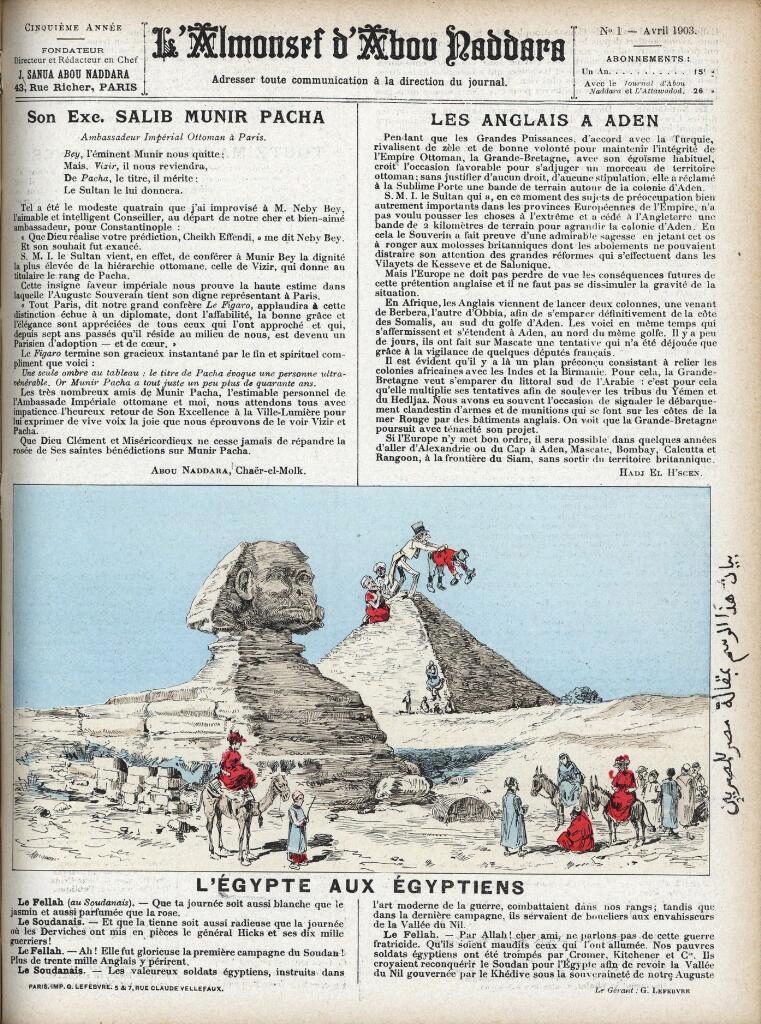

Egypt for Egyptians!

Sanua respected the rights of other countries, but he also expected them to butt out of Egypt’s business. Cover page caricature of foreigners being kicked off the pyramids. April 1903