Antiochus’ Castle

People generally assume the history of Hasmonean Jerusalem began with the Seleucid conquest of Judea from the Egyptian Ptolemies, escalated with Antiochus Epiphanes’ anti-Jewish edicts and the idol he placed in the Temple, and culminated with a small cruse of olive oil and Judah Maccabee’s great victory, which drove the wicked Hellenists from the land. In fact things were a bit more complex, and something much larger and more sinister than an idol loomed threateningly over the city for decades. It was called the Akra.

The Greek term akra, meaning castle or fortress, is also the source of the word “acropolis,” a fortified citadel dominating an area. When the Seleucids conquered a major city, they’d first destroy much of it, then erect a tower and station a well-equipped garrison there to maintain control. That’s exactly what Antiochus IV Epiphanes did after he captured Jerusalem in 169 BCE, as described in Maccabees I:

Then he fell suddenly upon the city and dealt it a great blow, destroying many people of Israel. He despoiled the city, burnt it with fire, and razed its houses and its surrounding walls. … They fortified the city of David with a high and strong wall with mighty towers, and it became their citadel. (First Book of Maccabees, trans. Sidney Tedesche [New York: Harper and Brothers, 1950], chap. 1, vv. 31–4)

First-century Jewish historian Josephus Flavius calls this fortress the Akra:

And he burnt the finest parts of the city and, pulling down the walls, built the Akra in the Lower City; for it was high enough to overlook the Temple, and it was for this reason that he fortified it with high walls and towers, and stationed a Macedonian garrison therein. (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, book 12, Loeb Classical Library vol. 5, trans. Ralph Marcus [Harvard University Press, 1943], p. 129)

These two books are the main sources we have for the history of the Hasmonean period – and of the Akra. They indicate that the garrison posted at the Akra was composed mostly of mercenaries, but it also included Hellenized Jews who saw themselves as part of the occupying power and were extremely hostile toward the city’s Jewish population. Maccabees I calls this group “sinful people,” while Josephus describes them as “impious and of bad character, and at their hands the citizens were destined to suffer many terrible things” (ibid.).

The Akra’s occupants made life in Jerusalem miserable. They hoarded weapons, stole household food, and murdered the city’s inhabitants. Thousands fled, until by 167 BCE the entire city had been abandoned – apart from the Akra. These conditions sparked the fire of revolt in Mattathias the Hasmonean’s native Modi’in and set the stage for the miraculous Hanukkah story. But even after Judah Maccabee’s great victory at Beth Horon in 166 BCE, nothing improved in Jerusalem:

Jerusalem was uninhabited like a wilderness; none of her offspring went in or out. The sanctuary was trodden down, and sons of foreigners were in the citadel. It became a solitary lodge for the heathen. Joy was removed from Jacob, and flute and harp ceased. (First Maccabees, chap. 3, v. 45)

After capturing and purifying the Temple in 164 BCE, the Hasmoneans made valiant efforts to subdue the Akra and banish its inhabitants, but that proved virtually impossible. Raised on a giant podium like an enormous, brooding monster, “high enough to overlook the Temple” (Josephus, Antiquities op cit.), the Akra was impenetrable. Judah and his men attacked its fortified defenses time after time, but despite the Maccabees’ unbroken string of victories, they couldn’t overcome the Seleucid soldiers mocking them from the Akra’s mighty ramparts, with their unscaleably slippery slopes.

A Poke in the Eye

Even after Antiochus IV Epiphanes’ young son Antiochus V succeeded him, nothing changed. Jerusalem was once again a bustling city with much of its activity centered on the Temple, but the Akra remained an eyesore, and its Hellenist occupants periodically lashed out at pilgrims and ordinary citizens alike. Fed up, the Hasmonean leaders laid siege, forcing their opponents to turn to Antiochus V for help.

Some of them escaped from the blockade…. They went to the king and complained, “How long will you neglect to do justice and avenge our brothers? … our people have become estranged from us and have laid siege to the citadel … as many of us as they find they put to death and seize our possessions…. Why, this very day they have besieged the citadel in Jerusalem to take it over…. Unless you stop them at once, they will do more than this, and you will not be able to check them.” (First Maccabees, chap. 6, vv. 21–7)

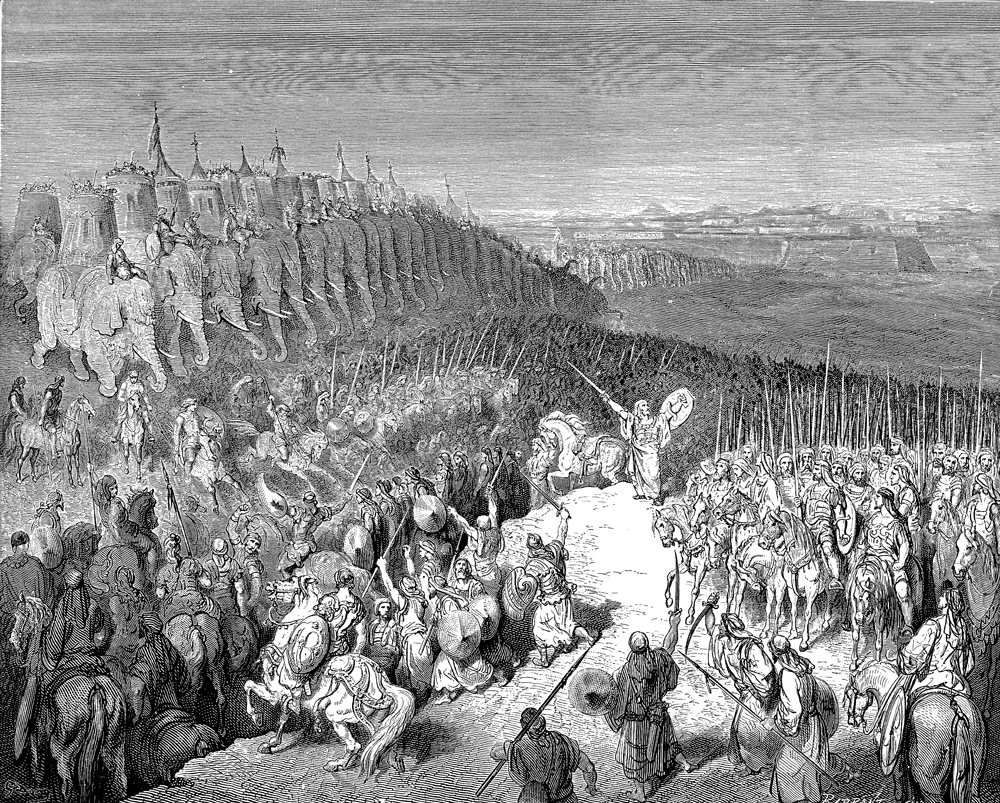

Despite the Hasmoneans’ many brilliant victories, the Akra’s capture remained an elusive goal. Judah Macabbee encourages his troops before attacking Nicanor’s in a 19th-century engraving by Gustave Doré

Antiochus duly sent his army to defeat the Hasmoneans. Arriving in Jerusalem, the Seleucids overran the Temple and surrounded Judah Maccabee’s troops, who’d barricaded themselves on Mount Zion. In the end the Seleucids withdrew to deal with unrest at home, leaving Judah in control of the city on condition that he lift the siege on the Akra. Jerusalem returned to normal – with the Akra and its troublesome garrison still sticking out like a sore thumb.

The Hasmoneans fought off most of the constant Seleucid attacks on the borders of the tiny Jewish commonwealth of Judea, which only increased their frustration with the fifth column in the very heart of their territory – the Hellenists in the Akra. The fortress conveniently sheltered warriors the Maccabees put to flight; Seleucid general Nicanor took refuge there, taunting the Jews with curses and threatening to burn down the Temple. (His subsequent attack failed.)

In 161 BCE Nicanor was soundly defeated by the town of Adasa, north of Jerusalem. Judah brought the general’s head and hand back to the city in a victory procession, calling on his enemies in the Akra to watch the spectacle:

… he sent for them that were of the tower, and shewed them vile Nicanor’s head, and the hand of that blasphemer, which with proud brags he had stretched out against the holy temple of the Almighty. … He hanged also Nicanor’s head upon the tower, an evident and manifest sign unto all of the help of the Lord. (Second Maccabees, The Temple Bible, ed. W. Fairweather [Philadelphia, 1967], chap. 15, vv. 31–5)

Once and For All

Judah Maccabee never saw the hated fortress fall, for he was killed in battle against Seleucid general Bacchides in 160 BCE. Like Judah, his younger brother and successor Jonathan did everything in his power to breach the Akra’s walls. Yet Bacchides strengthened its defenses and, anticipating a siege, stocked the place with provisions. He also kidnapped the sons of Jewish leaders and held them hostage within the Akra’s thick walls.

Jonathan, the most skilled diplomat of all the brothers (see The Youngest Maccabee), exploited divisions and succession struggles within the Seleucid royal house to earn the trust of Demetrius I, who usurped the throne of Antiochus V. Demetrius freed the prisoners held inside the Akra and promised Jonathan control of the fortress.

In 153 BCE, after a few years of waiting patiently while Jerusalem’s Jewish population continued suffering from outrages perpetrated by the Akra’s inhabitants, Jonathan besieged the tower. Demetrius summoned him forthwith but vowed once again to hand the Akra over. Once again nothing happened.

This time Jonathan tried a different tactic:

Here Jonathan gathered all the people together in the Temple and advised them to repair the walls of Jerusalem, … and, in addition, to build still another wall in the midst of the city to keep the garrison in the citadel from reaching the city, and in this way cut off [the garrison’s] large supply of provisions. (Josephus, Antiquities, book 13, Loeb Classical Library vol. 5, pp. 316–7)

Nonetheless, the Akra’s defenders had stockpiled enough food and water to hold out for ten years! Eventually, though, resources dwindled, just as a new leadership crisis arose in the Seleucid kingdom. Upstart general Diodotus Tryphon had seized control, murdering the boy ruler who’d inherited Demetrius’ throne. In 143 BCE Tryphon embarked on an all-out campaign to wipe out the small, stubborn Jewish community in Judea. He used a ruse to capture Jonathan, then prepared to come to the aid of the beleaguered Hellenists holed up in the Akra. Their triumph was short-lived, however. Jonathan’s older brother Simon managed to hold off Tryphon’s troops until a snowstorm forced their retreat. Unable to retake the fortress, Tryphon vented his frustration by executing Jonathan.

Determined to conquer the Akra, Simon – Jonathan’s replacement – tightened the siege until not even a fly could get in or out. One by one the defenders succumbed to hunger, finally surrendering to the Jews on 23 Iyar 141 BCE. The foreign threat had disappeared at last, gone the same way as the idol that had desecrated the Temple. Simon and his men staged a triumphal ceremony in the city:

They entered it on the twenty-third day of the second month … with praise and palm branches, with harps and cymbals, stringed instruments, hymns and songs, because Israel had been ridden of a great enemy. He ordained that they observe that day with joy every year. (First Maccabees, chap. 13, vv. 51–2)

This historic date is also included in Megillat Ta’anit, a first-century listing of days on which fasting is forbidden.

Razed to the Ground

Now that the Akra was in Jewish hands, the question was what to do with it. Integrated into Jerusalem’s defenses, the mighty fortress could make the city almost impregnable. On the other hand, destroying it was without doubt the best way to ensure that it never fell back into enemy clutches. Maccabees I tells us Simon’s initial decision:

They engraved this on brass tablets and set it upon pillars on Mount Zion. This is a copy of the inscription…. And in his [Simon’s] time everything prospered in his hands, so that the heathen were expelled from their country, as well as those in the city of David, in Jerusalem, who had made a citadel for themselves, from which they used to go out and pollute the environs of the sanctuary, doing great damage to its purity. He settled Jewish men in it [the citadel] and fortified it for the safety of the country and the city, and heightened the walls of Jerusalem. (ibid., chap. 14, vv. 26–37)

But once Simon’s autonomous Judea gained Seleucid recognition, the fear arose that these “allies” might eventually demand the Akra back. When Antiochus VII indeed asked for the keys in 134 BCE, Simon destroyed the Akra, podium and all:

And so they all set to and began to level the hill, and without stopping work night or day, after three whole years brought it down to the ground and the surface of the plain. And thereafter the Temple stood high above everything else, once the citadel and the hill on which it stood had been demolished. (Josephus, Antiquities, p. 337)

So Where Was the Akra?

More than two millennia have passed since then, and many imposing buildings – the Temple among them – have been destroyed in Jerusalem. Diligent archaeologists have uncovered most of them. Only one major structure from Second Temple Jerusalem remains elusive: the Akra. Very possibly, the fact that Simon the Hasmonean had it taken apart brick by brick means there’s nothing to find. But that hasn’t stopped lots of people from looking.

Professor Ronnie Reich of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), one of the foremost scholars on Second Temple Jerusalem, wrote in his book Invitation to Archaeology (Tel Aviv, 1995 [Hebrew]) that the Akra is probably the Holy Land’s largest ancient building of which we have a written record, but no one knows where it stood. Almost everyone who’s ever dug in the city has an opinion, and almost every corner in town has been advanced as a candidate.

It’s clear from the sources that the Akra was right near the Temple Mount and “high enough to overlook the Temple” (Josephus, Antiquities, p. 129). Maccabees I places the fortress in the City of David, and Josephus adds that the structure was in the Lower City as opposed to the Upper, but then it couldn’t have been taller than the Temple: the City of David and the Lower City were so much lower than the Temple Mount in Hasmonean times that the building would have had to be an eighteen-story, fifty-meter-high skyscraper – an engineering impossibility for that day and age (although that was in fact the height of the Temple Herod built a century later).

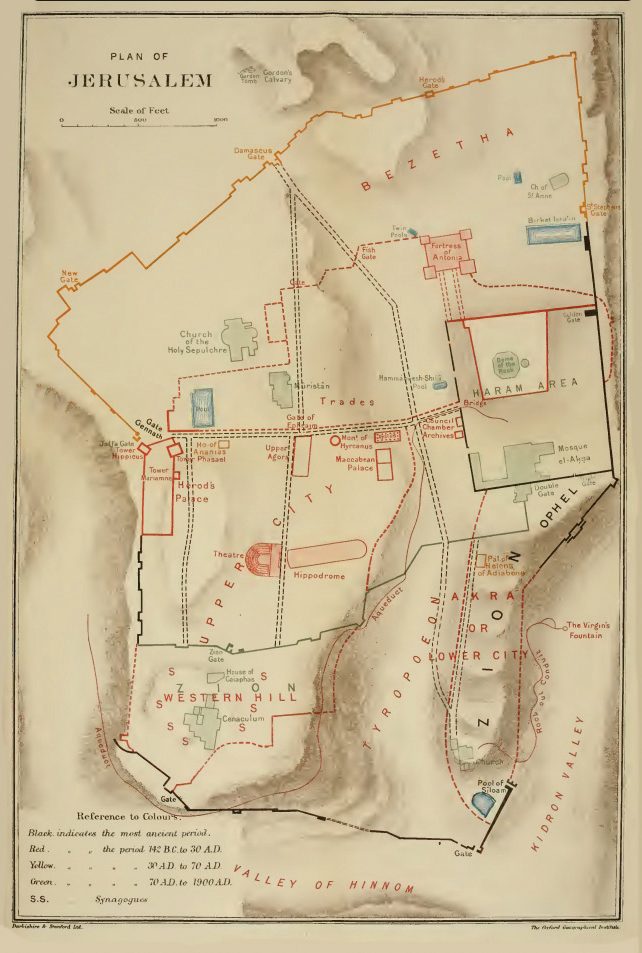

In an article published in 1979, archaeologist Yoram Tsafrir sketched a map of Jerusalem showing nine possible locations for the Akra, suggested by no fewer than twenty-five researchers. Six of them placed it in the Lower City. Others proposed the site of the Antonia Fortress, north of the Temple Mount; somewhere in the Upper City; on the Temple Mount; or on Mount Zion.

Color-coded map of Jerusalem’s development in various periods: ancient (black), Hasmonean and Herodian (red), Roman (yellow), and post-destruction (green). This map places the Akra in the Lower City, the City of David. From William Sanday and Paul Waterhouse, Sacred Sites of the Gospels (Oxford, 1903)

Like a number of archaeologists before him, the late Professor Michael Avi-Yona of the Israel Antiquities Authority supposed the Akra to have been in today’s Jewish Quarter. That fits the descriptions of the Akra towering over the Temple, but rather than being next to it, the fortress would have been on the other side of the Tyropoeon Valley.

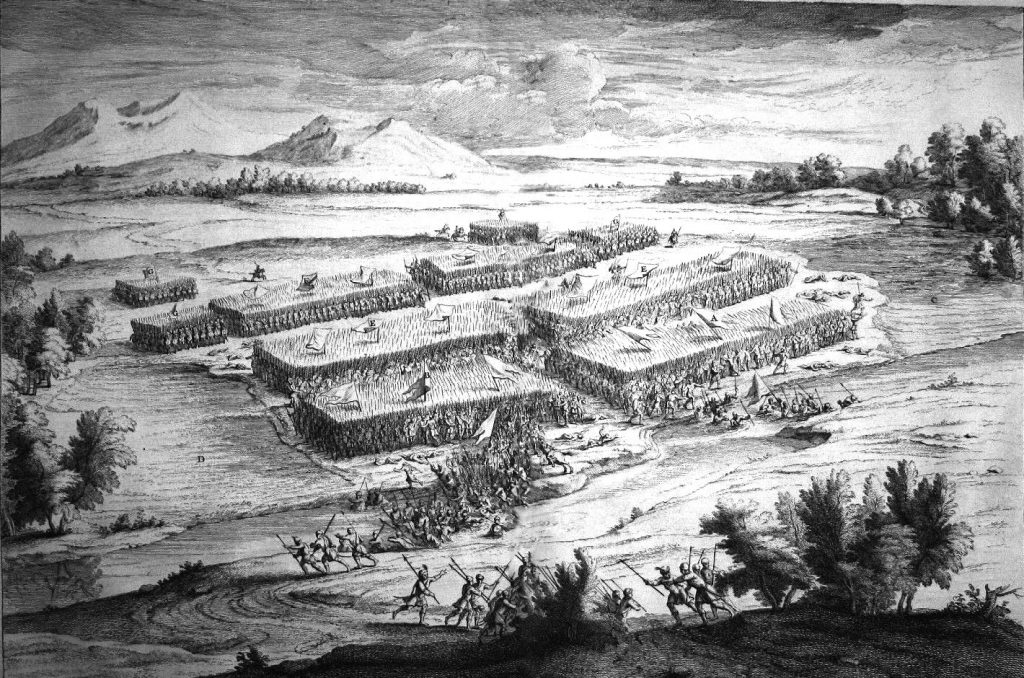

Herod built the Antonia Fortress in 35 BCE to give him and his Roman allies control of the Temple Mount. The Antonia in the model of Second Temple Jerusalem on display in the Israel Museum

Archaeologists Ben-Zion Loria and Hillel Geva put the Akra just north of the Temple, where the Bira (or Baris) fort built by Jerusalem’s Ptolemaic rulers had stood. This thinking reflects a widespread assumption that conquerors prefer to reinforce their predecessors’ fortifications – since these structures usually occupy the most defensible positions – rather than build anew. Herod also erected one of his three massive towers here, naming this fortress Antonia.

The problem with this theory is threefold: first, it contradicts Josephus’ Antiquities and the books of Maccabees, both of which locate the Akra much lower down, in the City of David. Second, it makes the description of the Akra’s podium superfluous, as this hill north of the Temple Mount was naturally high. Third, the Akra was built after the Ptolemaic fortress – which no side claimed to have destroyed – making it seem that these two towers were in separate locations.

The most original approach, which elegantly avoids the pitfalls of the previous two suggestions, is Yoram Tsafrir’s. He envisions the Akra on the Temple Mount. In the Hasmonean period, the Temple occupied a much smaller space than the expansive platform on which Herod rebuilt it a century later. That extension was mostly to the south, so if the Akra had stood next to the Temple at its southern end, it would have been buried under Herod’s platform. Tsafrir even claims that the seam in the oldest, eastern supporting wall of the Temple Mount shows where the remains of the Akra’s eastern rampart were incorporated into the wall. Of course, there’s no way of proving this theory, as no excavations can be undertaken on the Temple Mount.

Big News?

Other researchers take the sources at their word and locate the Akra in the Lower City, south of the Temple Mount. Archaeologist Meir Ben-Dov suggested a site in the area of the Ophel excavations, south of the Old City’s southern wall. Historian Bezalel Bar-Kochva dragged the Akra even farther south, into the City of David, and archaeologist Gabi Barkai located it at that area’s southernmost point, today known as the tombs of the House of David.

Akra or not, the fortress recently exposed in the City of David excavations is clearly a Hellenist structure with impressive defenses, including thick walls, towers, and a glacis, or slope

After many years of excavating the area known as the Givati parking lot (across from the City of David national park), archaeologist Doron Ben Ami has joined this camp, based on several recent finds: a section of heavily fortified wall, possibly the one built by Jonathan the Hasmonean to cut the Akra off from its supply lines; part of an enormous tower four meters wide and twenty meters high; and the remains of a steep glacis (the proverbial slippery slope, intended to stop invaders scaling a castle’s walls). Dozens of Hellenist coins found here, bearing the names of Seleucid kings from Antiochus IV to VII, suggest that these structures date back to the Hasmonean period, when the Akra cast its shadow over Jerusalem.

Two hundred amphora handles stamped with the seal of the Isle of Rhodes show that the tower’s inhabitants were either non-Jewish or non-observant. And an enormous number of bronze arrowheads and lead slingshots uncovered nearby, typical of those used by Hellenist armies, testify to the fierceness of the battles fought at this site. The positions of these artifacts indicate that they were directed against attackers coming from outside the tower. All this accords with accounts of repeated Hasmonean attempts to wrest the Akra from the hands of the Hellenists. It sounds like big news.

Unfortunately, the excitement of this startling discovery has been somewhat dampened, as three strong objections to the identification of this fortress with the Seleucid Akra remain. The structure isn’t close enough to the Temple Mount (especially considering the size of the Temple in Hasmonean times) to match the ancient sources’ descriptions; it’s extremely unlikely that it was tall enough, even if built on a giant podium, to overlook even the Hasmonean Temple, which was topographically much higher; and it has walls and towers, while the Akra was supposedly utterly demolished.

On the other hand, it is definitely a Hellenist fortress from the right period, and none of our sources mention any other such large tower in Jerusalem. If this is indeed the Akra, we have to discount the depictions of its size and demolition in both Josephus and Maccabees as exaggerations.

This slingshot marked with a Seleucid symbol was discovered not far from the Akra and was apparently shot from within its walls

These Seleucid arrowheads and slingshot discovered within bow-shot of the fortress were pointing in the direction of approaching foes

So have we found the Akra in the Givati parking lot? In any case, the Hellenist fortress discovered in the City of David clearly played an important role in Hasmonean Jerusalem and reminds us – just in time for Hanukkah – that a great miracle indeed happened here.

Further reading:

Bezalel Bar-Kochva, Judas Maccabaeus: The Jewish Struggle against the Seleucids (Cambridge University Press, 1989), appendix D; Ben-Zion Mazar, M. Yonah, and Meir Ben-Dov, The Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem (near the Temple Mount) (Institute of Archaeology, 1969)