Limestone or Marble?

As a Jew trying to tell the history of his people to a non-Jewish audience, Josephus, the Jewish historian of the Second Temple period, was clearly in a delicate position. At the very beginning of The Jewish War, Josephus testified:

In these circumstances, I – Josephus, son of Matthias, a Hebrew by race, a native of Jerusalem and a priest, who at the opening of the war myself fought against the Romans and in the sequel was perforce an onlooker – propose to provide the subjects of the Roman Empire with a narrative of the facts, by translating into Greek the account which I previously composed in my vernacular tongue and sent to the barbarians in the interior. (Josephus, The Jewish War, I, Loeb Classical Library [hereafter LCL], p. 3,)

Modern researchers’ interface with ancient texts is always fraught, as the authors frequently interwove fact and fiction in their “histories.” Josephus Flavius – who adopted the name of his Roman patrons, Vespasian’s Flavian dynasty – is an extreme case. It sometimes seems as if criticism of the turncoat Jewish historian has only sharpened over time.

As an archaeologist, I couldn’t ignore the challenges posed by Josephus’ breathless descriptions of Judea. Most glaring was his reference to the marble used in Herod’s construction projects. Six times, Josephus refers to marble structures – in Banias, Herodium, Antioch, Hebron, and Jerusalem. Yet excavations of Herodian sites have unearthed no marble. My inescapable conclusion: Josephus had amateurishly mistaken local limestone for marble. Indeed, in his later writings, Josephus no longer mentions marble. In Rome, apparently, he learned the difference between various types of stone.

Nevertheless, I found myself wondering whether there might not be some measure of truth in Josephus’ accounts. Marble was imported into Herod’s Judea, but it was reserved for opulent colored floors, tiled using a method known as opus sectile.

In Latin, opus means “work,” and sectile, “cut” or “divided.” In opus sectile, then, large stone slabs of various colors are cut in geometric shapes and combined to form patterns. The technique first appeared in the Hellenistic world in the fourth century BCE, mostly in fairly simple designs. These became more complex, sometimes including plant or animal shapes. Opus sectile graced lavish residences and public buildings, especially baths, from the Roman period onward. As the most expensive flooring available, it was clearly a status symbol.

Herod, a well-known admirer of Roman architecture, invested heavily to bring opus sectile to Judea. Importing marble and other types of stone from all over the Roman Empire, he included these geometric patterns in his palaces around the Holy Land. Though most of the stone has been stolen and the floors haven’t survived, you get the idea from the small sections still remaining and from impressions in the plaster. Examples have been found in Herod’s third palace in Jericho, in the bathhouses at Masada, Herodium, and Cypros, in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City, and even in Jordan, in the bathhouse at Machaerus and in a room in the Dead Sea oasis of Callirrhoe. Opus sectile is also visible in the remnants of a manor in Zikhron Yaakov as well as in a structure in Banias.

Stone of Many Colors

Suddenly these fragments began forming a pattern of their own. Excavating the Ophel area south of the Temple Mount, Prof. Benjamin Mazar came across an inscription in Greek, though one corner was missing. Dating from 17 BCE, the twentieth year of Herod’s reign, the find was essentially a donor’s plaque, recording the donation of stone flooring by a native of Rhodes:

In the twentieth year [of Herod’s reign], in the high priesthood of [x], Paris son of Akson [who dwells/is in] Rhodes [donated] for the floor tiles [x sum of] drachmas. (Benjamin Isaac, “A Donation for Herod’s Temple in Jerusalem,” Israel Exploration Journal 33, [1983], p. 86)

Discovered by Prof. Benjamin Mazar in the Ophel excavation by the Old City’s Dung Gate, this Greek inscription commemorates a donation of flooring for the Temple Mount

Josephus described the magnificent floor adorning the courtyard of the Temple Mount: “The open court was from end to end variegated with paving of all manner of stones” (Jewish War, V, LCL, p. 257). This depiction strengthens Prof. Benjamin Isaac’s assumption that the donation pertained to this flooring. But did the floor feature opus sectile tiling or something a little less exotic, such as the plain but well-crafted flagstones used to pave open streets in Herodian Jerusalem?

The Greek word Josephus applied to the flooring was ποικίλος, meaning colorful patchwork. In Henry St. John Thackeray’s translation of The Jewish War for Harvard University Press, published in 1927, he renders this adjective as “variegated with all manner of stones.” Josephus used the same Greek term to describe the floor of the bathhouse in Masada:

The fittings of the interior – apartments, colonnades, and baths – were of manifold variety and sumptuous; columns, each formed of a single block, supporting the building throughout, and the walls and floors of the apartments being laid with variegated stones. (ibid., VII, LCL, p. 587)

Yigael Yadin’s 1963–5 excavations of Masada’s large bath house uncovered colorful stone pieces still in position as part of the original floor. This exciting confirmation of Josephus’ description suggests that by the Greek ποικίλος, he meant opus sectile. The method had clearly impressed him.

The Temple courtyard’s grandeur is also extolled in later Jewish sources. The Talmud discusses Herod’s immense building projects in Jerusalem, including his use of high-quality marble:

Whoever has not witnessed the rejoicing at the place of the water-drawing has never seen rejoicing in his life. Whoever has not seen Jerusalem in its splendor has never seen a beautiful city in his life. Whoever has not seen the Temple fully reconstructed has never seen a glorious building in his life.

Which Temple? Abaye, or perhaps Rabbi Hisda, replied, “This refers to the one built by Herod.” Of what did he build it? Rabba replied, “Of white and gray marble.” Some say, “With white, black, and gray marble.” He made one row protrude and inset the next, in order to provide a hold for the plaster. He intended at first to overlay it with gold, but the rabbis told him, “Leave it alone. It is more beautiful as is, for it resembles the waves of the sea.” (Sukka 51b)

Perhaps it was the colorful stone floor of the courtyard that lingered in rabbinic memory after the Temple’s destruction, morphing into a description of the sanctuary itself.

Challenging the Imagination

I recorded my conclusions in a paper for the Hebrew University’s Archaeology Department in 2006. I was working at the time at the Temple Mount Sifting Project. Under the direction of Dr. Gabriel Barkai and Zachi Dvira, volunteers have been sifting through the thousands of tons of earth illegally removed from the Temple Mount in 1999 by the Islamic Movement.

Chunks of black stone were already noted in initial evaluations of the heaps of dirt brought to the Zurim Valley National Park; the stone came from bitumen rock, rich in organic material. These modern-looking fragments were at first presumed to be recent construction waste. But when complete, measurable pieces surfaced, it became apparent that some of their dimensions matched those of stone used for opus sectile at other Herodian sites.

Could these finds be remnants of the stone floor of the Temple courtyard, just as Josephus had described it? I presented my hypothesis at a conference at Bar-Ilan University in 2007.

Comments followed thick and fast, critical as well as complimentary: maybe Josephus’ descriptions were exaggerated, and my conclusions even more so? The late Prof. Ehud Netzer, who discovered Herod’s tomb and theater at Herodium, objected that opus sectile was unlikely to have been used in any open space, certainly not the Temple court. But Netzer himself had uncovered an out-door area paved with opus sectile outside Herod’s third Jericho palace. He had suggested that this space had been part of a building with a high ceiling. Yet the gaps between the columns supposedly supporting such a ceiling were thirteen meters wide, rendering this theory implausible. Rather, the Jericho floor was probably part of a courtyard surrounded by pillars.

Jericho was central to Herod’s administration and his kingdom’s economy, and he built three palaces there. Impressions left in a floor in the third palace show that it was originally tiled with stone and marble in opus sectile

As Herod’s Temple Mount included the largest temenos, or sacred courtyard, in the Roman world of his time, he may well have challenged contemporary imaginations by paving the plaza with opus sectile, generally reserved for much smaller spaces.

Saved from the Rubble

Initially highly speculative and barely supported by facts on the ground, my thesis now appeared to be substantiated by a solid body of evidence. Thousands of fragments of colored stone tile emerged from the sifting project over the years.

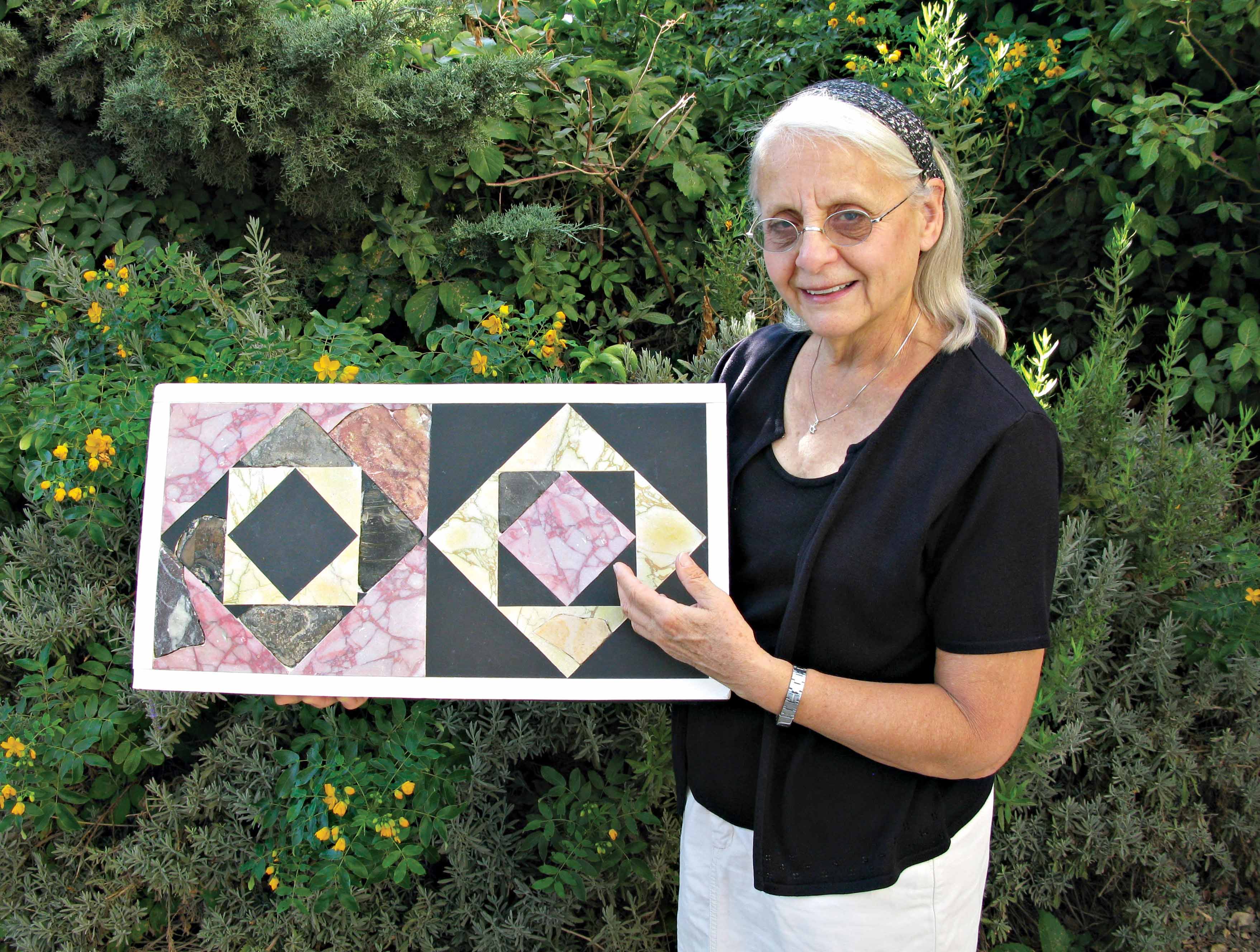

In 2007, new immigrant Frankie Schneider joined the effort. Though she had no archaeological background, Schneider proved to be a first-class researcher, having spent most of her life in the fields of statistics and mathematics. Analyzing measurements and angles, she produced a “best-guess” mock-up of the geometric floor patterns decorating the Temple courtyard.

Schneider published her results in 2016, comparing shapes found in the Zurim Valley excavation with designs occurring elsewhere in the Roman Empire at this time. Her reconstruction received broad press coverage both in Israel and well beyond.

Adding it up. Statistician and mathematician Frankie Schneider with her mock-up of Temple floor designs, based on finds from the Temple Mount Sifting Project

The conclusions drawn regarding the Temple flooring have sparked further research into opus sectile at other Herodian sites, including Cypros and Herodium. The pinnacle of our work came in 2012, when Schneider and I were consulted on the monumental Israel Museum exhibition Herod the Great: The King’s Final Journey. We helped reconstruct an entire Herodian floor, an unforgettable experience marked by singular enthusiasm on the part of all involved. It felt as if we were bringing the dead to life. Hundreds of thousands viewed that exhibition, including its colorful opus sectile floor. Exuding wealth and power, it exemplified the architectural magnificence that Herod, king of Judea, had sought to achieve.

Josephus, it turns out, left us not only the most dramatic living testimony regarding the events of the Great Revolt, but careful descriptions – accurate in far greater detail than researchers ever dreamed – of the backdrop against which they took place. They allow us to recreate some aspects of late Second Temple architecture with reasonable certainty, restoring an integral part of Israel’s cultural heritage – and the world’s – hopefully never to be lost again.