Has the Old Man Lost His Mind?

What was David Ben-Gurion’s most significant accomplishment? Most people would probably choose the declaration of the State of Israel. In retrospect, however, even more important than creating the state were his efforts to ensure its survival.

As soon as he was assigned the defense portfolio at the Jewish Agency (later to become Israel’s provisional government) in 1947, Ben-Gurion organized his own crash course to bring himself up to date. For several weeks, he met with representatives of each branch of the defense establishment and studied the organizational structure of the security forces –Hagana. He checked out its equipment, commanders, and strategy, the kinds of threats it was prepared to repel, as well as the strength and capabilities of the Arab enemy forces. His conclusions were radical – as was his reaction. He replaced several of the Hagana’s leading figures and, more important, created a significant shift in its thinking. Hagana activists were still gearing up to fight yesterday’s war – an intensified replay of the civil unrest and riots of the Arab Revolt a decade earlier. Ben-Gurion demanded that his troops be prepared to face organized, fully equipped military forces – the armies of the neighboring Arab states, including the Arab Legion stationed in Transjordan – rather than the local rabble and volunteer units his commanders expected. Hearing Ben-Gurion’s insistence on a real army, complete with tanks, planes, cannons, and battleships, many of his colleagues declared the old man out of his mind.

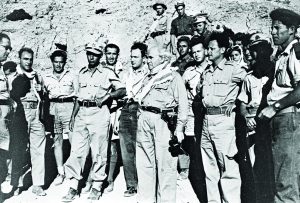

Seeking firsthand information on all branches of the IDF, Ben-Gurion spent a week on an Israeli navy boat in the summer of 1949. Conferring with the ship’s officers at sea

Not surprisingly, Ben-Gurion didn’t achieve all his goals before independence. The Hagana was fully restructured only later; during the War of Independence, almost all the prominent commanders were former members of Hagana or Palmah (its standing militia), and only a few had been formally trained by the British army. But Ben-Gurion’s success in shifting attention to the impending military threat proved critical. As a result of his vision, tremendous energies were diverted to acquire planes, tanks, and cannons during the months preceding the declaration of the State of Israel – most of which arrived in the course of the War of Independence. It is appalling to imagine the fate of the Jewish community had its security forces fought that war equipped solely with the two tanks (only one of which worked) and the single fighter plane they’d had when the state was declared. The Arabs had dozens of tanks and aircraft at their disposal, and no lack of ammunition.

Ben-Gurion envisioned a modern army equipped with tanks, planes, and battleships as well as rifles and artillery. With the crew of the Dakota, which flew him to Eilat in 1949

Thanks to Ben-Gurion’s ongoing efforts, fighter planes and weapons were purchased from Czechoslovakia in 1947–1948, volunteers were recruited from Jewish communities worldwide as of January 1948, and ships loaded with firearms and ammunition sailed from Europe and the United States. Without the resulting shift in the balance of power, giving the IDF an advantage over the Arab forces on nearly all fronts by early 1949, it is doubtful whether the State could have been established at all, let alone been able to defend itself.

A United Army

Ben-Gurion’s military strategy in the War of Independence has generated extensive discussion, eliciting effusive praise from some quarters and the harshest criticism from others. His insistence on forcing a route to Jerusalem resulted in the tragic battles at Latrun; his bold, if not crude attempts to restructure the military led to “the Generals’ Revolt,” in which nearly the entire Hagana command threatened to resign one week before the State of Israel was declared; his central role in the destruction of the Irgun militia’s weapons on the Altalena evokes fistfights to this day; and many still resent his ruthless dissolution of Palmah after the war. Although these incidents are not usually linked, they all ensured the formation of a unified army subordinate to Israel’s political leadership.

Touring the Negev with Yitzhak Rabin – one of many Palmah officers absorbed into the IDF high command – shortly after the War of Independence

Shortly after the State of Israel was established, a group of Palmah intellectuals including Natan (Yonatan) Klein, Haim Gurfinkel (Gouri), and Haim Feiner (Hefer) demanded that Ben-Gurion disband the Irgun and Stern Gang militias, which refused to accept central authority. Responsibility for all military operations, the group argued, should be transferred to Hagana, which was closely aligned with the state leadership. When he felt the time was ripe, Ben-Gurion acted mercilessly. Sinking the Altalena with all the ammunition on board was a price he was prepared to pay, though all the Jewish militias desperately needed weapons, and despite the fact that his decision nearly led to civil war. The Tel Aviv Palmah activists who willingly executed the operation had no idea that to Ben-Gurion’s mind, they posed a similar danger of insubordination.

Ben-Gurion also considered the alliance between Palmah and the National Kibbutz Association, associated as it was with Mapam (the United Workers Party), a significant threat. These concerns, together with his determination to rebuild the IDF as a regular army along the lines of the British model, led him to defiantly dissolve Palmah only months after the State of Israel had been established. Ben-Gurion was well aware of Palmah’s crucial contribution to Israel’s victory in the War of Independence, but he also realized that the organization saw itself as an elite and refused to take orders from above. As poet Natan Alterman wrote in his weekly column in Davar a week before independence, Palmach was an organization “that refused to leave any of the work to ‘outsiders,’… who write their own odes and have already set down their own version of history.” (“The Seventh Column,” Davar, 28 April 1948)

After the War of Independence, despite the fragile peace, Ben-Gurion deemed the IDF too large. His radical restructuring and cutbacks resulted in the resignation of Chief of Staff Yigael Yadin in 1952. Yadin was convinced that Ben-Gurion was weakening the army and endangering Israel. But Ben-Gurion saw the IDF as just one component of Israel’s overall security, and reasoned that allocating an oversized portion of the tiny state’s budget and resources to the military would eventually jeopardize the entire country. Foreseeing little risk of war in the coming years, he preferred the short-term gamble of downsizing the army, allowing him to invest long-term in the new state’s many civilian needs.

Given the enormous challenge of mass immigrant absorption, Ben-Gurion even diverted army forces to the civilian tasks of education and infrastructure. New chief of staff Mordechai Maklef was instructed to continue the reforms. The result was the basis of the IDF as we know it – a relatively small core of full-time soldiers backed by a much larger reserve force, with an emphasis on intelligence, the air force, and mobile ground forces (infantry and tanks). Moshe Dayan, Maklef’s successor, worked to strengthen morale and operative success, both of which suffered in the early days of the IDF.

Eighteen Points

Ben-Gurion arranged another “seminar” for himself in 1953, this time focusing on the optimal defense strategy for the State of Israel. Between August and October 1953, he visited the various IDF units, attended General Staff meetings, and held numerous discussions on the subject. The resulting “eighteen-point plan” has been the linchpin of Israel’s defense strategies ever since. Though not confined to military issues, this comprehensive document resolved several disputes over the structure of the armed forces. It emphasized the need to formulate long-term plans, increased the number of front-line troops while cutting back on support units, developed a reserve call-up system, increased allocations for equipment and reduced personnel, and transferred responsibility for the IDF’s budget to the Ministry of Defense.

The IDF’s first tanks were two Cromwells and two Shermans stolen from the British army, later joined by some ten obsolete French Hotchkisses. Thirty more Shermans arrived in 1949, purchased in Italy from American army surplus. A few were proudly displayed at a Tel Aviv military parade on Independence Day, 1949

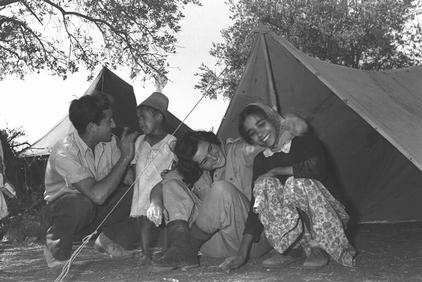

The plan also included programs designed to turn the IDF into the “melting pot” of Israeli society: seminars emphasizing classic Jewish moral and cultural values; patriotic history courses and field trips; and integration of soldiers from all ethnic backgrounds into heterogeneous units. “A nation cannot fight if it is not united,” announced one of its clauses. The army was to provide employment in areas with heavily immigrant populations, settle immigrants with an eye to reinforcing Jerusalem and its environs as well as the south, and make the Galilee and Nazareth overwhelmingly Jewish. Even further from conventional military priorities were “developing civilian aviation and seamanship” and “youth immigration from North Africa and South America” (Noam Tibbon, “1953: The Year the IDF Was Made,” Ma’arakhot 438 (2011), p. 25 [Hebrew]).

Two soldiers entertain immigrant children at a transit camp in Kisalon, December 1950

In his parting letter to the IDF in December 1953, Ben-Gurion wrote that national security was dependent on ethnic unity, mutual respect, and settlement (ibid., p. 26). Tanks and warplanes were important, but so was social equality. Ben-Gurion’s security policy boiled down to roughly three things: deterrence, alertness, and resolute action – priorities that guide Israel’s defense policies until today. Recent criticism and prolonged General Staff attempts to come up with a new formula ended up just adding the word “defense” to the original list.

Ben-Gurion was largely responsible for Israel’s victory in the War of Independence; his vision defined the IDF’s role within the State of Israel; and his defense policy has remained virtually unchanged for sixty years. The fact that all this was achieved by one person is extraordinary – even if the results were not perfect and the price they exacted was a heavy one. Who but David Ben-Gurion could have done so much?