Nothing to Say

There’s an old joke about a boy who hadn’t uttered a word since birth. Years passed, until one evening, he turned to the person sitting next to him at the dinner table and asked him to pass the salt. When asked why he had never spoken before, he replied with a shrug, “I didn’t have anything to say.”

The film industry was silent throughout its first thirty-two years, but not for lack of what to say. Silent movies were packed with artistic innovations and social as well as moral statements; the technical limitations of the medium were the only reason they lacked a voice. Still, in comparison with The Jazz Singer, they’re like the mute boy at the dinner table – they have nothing to say. The first sounds to issue from the silver screen did more than mark the end of the silent film era. They echoed with the existential questions haunting the filmmakers and much of their audience: who am I, and where do I belong? And the way the cinema framed these questions in 1927, in the first feature-length film with synchronized dialogue, was typically Jewish.

Mute Melodrama

The poster advertising The Jazz Singer omits any mention of sound, yet gives particular prominence to cantor Yossele Rosenblatt’s cameo performance. Was Warner Brothers hedging its bets?

The fact that all its characters were mute forced the young film industry to adopt a melodramatic style quite contrary to its inventors’ intentions. The first silent clips, screened at a small Parisian café on Friday night, December 28, 1895, were entirely realistic. They focused on mundane, everyday events – workers leaving a factory, a train pulling into a station, and a snowball fight on the streets of Paris.

Auguste and Louis Lumière had hoped the moving images captured by their cameras would open people’s eyes to the uniqueness of each moment in their lives. But the Lumières’ inability to integrate their pictures with a recorded soundtrack detracted drastically from the realism they’d hoped to achieve. The silent motion on screen was so far removed from the noisy world of its audience that it lacked credibility; the grandiose gestures with which the actors attempted to compensate for the lack of dialogue, and the live music played to accompany the silent screen, pushed the medium toward escapism, histrionics, and extreme artistic experimentation.

For many filmmakers, such limitations were untenable. Artists dreamed of films that would “hold a mirror up to nature,” and the search for a technical solution that would tear down the sound barrier dividing reality from the silver screen became a challenge attacked by engineers from every side.

The long-awaited breakthrough was finally achieved in the mid-1920s. Western Electric developed the “Vitaphone” and offered it to leading Hollywood studios. This technique connected the film projector to a phonograph. A slight time lag remained between the actors’ facial expressions and the sound, but short scenes in which the cast’s voices were projected over prerecorded background music could now be integrated into otherwise silent films.

Studio owners were skeptical. Incorporating the Vitaphone into movie theaters was complex and expensive, and who knew whether the new technology would be a hit? Faced with a choice between guaranteed income and a risky investment in the film industry’s future, moguls preferred their cash in hand. In desperation, Western Electric finally peddled their product to the ambitious managers of a small, dynamic studio, who agreed to give the Vitaphone a chance.

Courtesy of Ianvannest

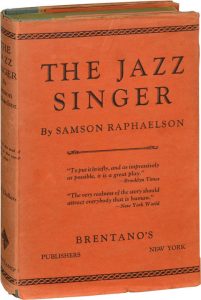

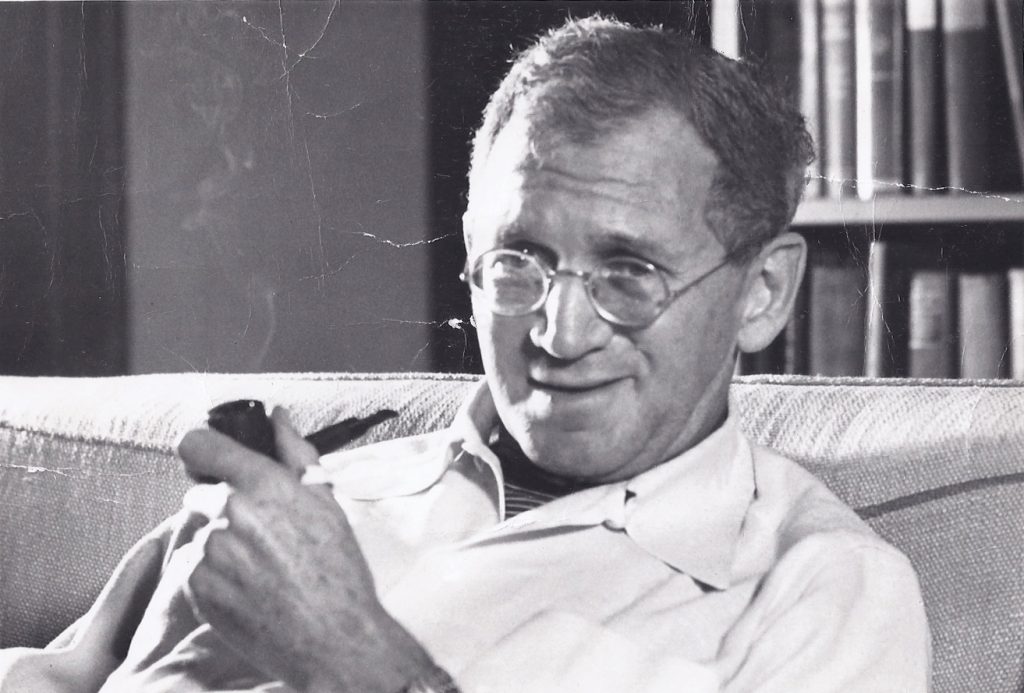

Courtesy of Ianvannest The Jazz Singer was Samson Raphaelson’s first play, adapted in just one weekend from his short story. The film launched him as one of Broadway’s most successful and prolific playwrights. Raphaelson and below, a copy of his play

The Screen Comes to Life

The four Warner brothers – Albert, Harry, Sam, and Jack – had been a part of the film industry since 1903. Their chain of movie theaters provided a decent income for the family, but the Warners were determined to work their way up and create their own films instead of selling and distributing those produced by other studios. The small, family-owned studio was falling behind the big names; its only big success had been its Rin Tin Tin series, featuring the exploits of a daring dog.

Generation gaps often center on the tension between modern and traditional values. Jakie serenades his mother in a scene from The Jazz Singer

Relations between Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack Warner were fine when they set up Warner Brothers, but later deteriorated, culminating in a takeover engineered by Jack Warner in 1956. Sam, the brother who pushed hardest for the introduction of sound, died and was buried the day The Jazz Singer premiered

Unlike Paramount and MGM, Warner Brothers had nothing to lose. They hoped the Vitaphone would be the breakthrough they’d been looking for. In 1926 they began showing short talkies as a warm-up to their main, full-length features, which remained silent. Finally, in late 1927, the time was ripe for the appearance of The Jazz Singer, the first full-length motion picture to include sequences with dialogue. Though silence dominates the eighty-eight-minute film, sound breaks through briefly at several points. In the climactic final scenes, the actors can be heard speaking – and singing. Finally sound had come into its own. The Jazz Singer proved conclusively that pictures and sounds could indeed be synchronized, and marked the beginning of the end of the silent movie era. For the first time, sound was introduced not as a gimmick but as an integral part of a film’s story line. The actors’ initial silence symbolized repressed parts of their characters; they finally began speaking only when the progression of events allowed them to “find their voice.”

A Wrenching Dilemma

The Jazz Singer is Alan Crosland’s film adaptation of a play by the same name written by Samson Raphaelson, a prominent Hollywood screenwriter. The play was based on a short story by Raphaelson called “Day of Atonement,” which had appeared in Everybody’s Magazine in January 1922. Jack Robin, formerly Jakie Rabinowitz, hails from a dynasty of Jewish cantors. He dreams of breaking the mold and making a name for himself in the nightclubs and concert halls frequented by the younger generation. His spirit chafes at the traditional melodies of the synagogue, yearning to express itself in the freedom of jazz. In the film, Jakie is played by Al Jolson, born Asa Yoelson, a well-known entertainer and himself a cantor’s son. Jakie’s father pressures him to abandon his newfound love and remain within the Jewish community. Sold on jazz, convinced that it captures the spirit of the age, Jakie leaves home.

Years later, the long-lost son is summoned to his father’s deathbed. On Yom Kippur eve, Jakie’s parents and their entire community beg him to sing the Kol Nidrei prayer in the synagogue that evening instead of his father. But that evening is the opening night of a show that could be the long-awaited turning point in Jakie’s career. Torn between his family, his Jewish identity, and the American individualism on which he’s built his life, Jakie has to choose.

The Jazz Singer is a journey between identities. It begins with the Jewish community’s attempt to imbue young Jakie with traditional values. These Jews expect him to play his part, dutifully passing the torch of faith and tradition to the next generation. Aware that by succumbing to the temptations of the outside world, he could sever his connection to his roots forever, Jakie risks becoming a stranger to his own family. For Raphaelson, the greatest pull of tradition was the warm embrace of the Jewish home. As Tevye the milkman says in Fiddler on the Roof, “Because of our traditions, every one of us knows who he is, and what God expects him to do.” Secure in that knowledge, “every one of us is a fiddler on the roof, trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune without breaking his neck.”

Jakie’s problem is that the “pleasant, simple tune” is no longer enough. He is drawn to the world beyond his community, where each individual defines himself, making the collective irrelevant. With Judaism no longer a liability, he has no need for the warmth of a support group. The community’s sheltering wings are suffocating, preventing him from spreading his own. Yet anxious as he is to break away from Judaism, when it comes to cutting his ties to his father, and particularly his mother, he hesitates. Traditional ideals may seem meaningless in the modern world, but everyone needs a home and a family. How can he throw away the trappings of religion without losing his family, the kernel of his being?

Staring Back from the Mirror

One of the film’s most poignant scenes occurs on the eve of the Day of Atonement, just as dress rehearsals for Jakie’s opening night performance are to begin. Sitting in his dressing room, Jakie is wracked with indecision. The soundtrack plays several notes of Al Jolson’s hit song “Mammy,” and Jakie’s gaze settles on a photograph of his mother on the table. His beloved Mary enters the dressing room and sees the grief in her lover’s eyes. She realizes he’s worried about his father. Jakie tells her how torn he is, adding, “I don’t really belong there – here’s where I belong, on Broadway. But there’s something in the blood that sort of calls you – something apart from this life.” Mary nods understandingly but reminds him: “No matter how strong the call, this is your life.”

Jakie rises determinedly and starts making up for the show. In the mirror, he sees the synagogue as he imagines it. The soundtrack, too, reflects his thoughts, playing the familiar notes of Kol Nidrei. He bangs his fist on his chest, as is customary when saying the confessional prayer of Yom Kippur. “The Day of Atonement is the most solemn of our holy days,” he bursts out, “and the songs of Israel are tearing at my heart!” His girlfriend tries to save him from his anguish. “Your career is the place God has put you. Don’t forget that, Jack,” she reminds him. He agrees, adding, “My career means more to me than anything else in the world.” “Even more than me?” she asks. “Yes,” he answers, “even more than you.” Her winning smile proves that she has made her point. “Then don’t let anything stand in your way!” she says. “Not even your parents, not me, not anything!”

Jack’s dilemma is clear. Stuck between the ties of tradition and the allure of modernity, he realizes that though the bright lights may dazzle, they don’t guarantee happiness. The price of success is life without a home, without family and community, forswearing love for the false comforts of fame and fortune.

This scene, like many others depicting Jakie’s inner turmoil, is silent. His lips move, but his voice is unheard. Torn between conflicting worlds, represented by two musical themes on the soundtrack – one hauntingly Jewish, the other typically American – Jakie struggles to find his own path, his own voice. Unable to appreciate his own worth, he is dumbstruck figuratively as well as literally, finding solace only in thoughts of his distant mother.

Jakie pines for his mother’s warmth, not for the rigors of his forefathers’ traditions. He knows he will never find its substitute in show business. It is no coincidence that the first sounds in the film are related to his mother. In one scene, he visits her without his stubborn father’s knowledge and serenades her with a song from his current show – “Blue Sky” by Irving Berlin (born Israel Beilin). Mother and son relish these stolen moments and the forbidden music played on a piano usually reserved for holy melodies. On the soundtrack, we hear the mother harmonizing with her son as the music bridges the gap between them. In another scene, Jakie attends a performance by cantor Yoselle Rosenblatt. In this vintage performance by the famous Rosenblatt, we hear the Yiddish song “The Memorial Candle,” which reminds Jakie of his mother and her slowly fading world.

-

-Rabbis and cantors on the silver screen. Scenes from The Jazz Singer

To Wild Applause

To find his voice, Jakie must first find the path that suits him and his generation. He embraces both the warm, maternal atmosphere of the traditional world and the modern freedom to realize his dreams and utilize his talents to the full. He rejects his father’s values and the temptations of wealth, leaving behind the restrictions of Judaism to pursue the American dream. Yet even as he ventures further into the outside world, he steers homeward. Having succeeded in bridging two worlds, Jakie finally finds his voice. He chants Kol Nidrei in his father’s stead, but as a “jazz singer singing to his God,” as his girlfriend puts it. His mother enters the music hall, and he dedicates a song to her as the audience cheers – both on screen and off.

At the beginning of the film, secular and sacred seem irreconcilable. By the end, we understand that the two worlds need not conflict. “Jazz is prayer,” claimed the souvenir program that accompanied the movie, quoting Raphaelson’s preface to his play. “It is too passionate to be anything else.” And the author goes further: “One of the Americas of 1925—that one which packs to overflowing our cabarets, musical revues, and dance halls—is praying with a fervor as intense as that of the America which goes sedately to church and synagogue.” The film producers aspired to reconcile the two Americas and bridge the generation gap between immigrant parents and their assimilated children. But that required the parents to recognize the legitimacy of their children’s ways, admitting that jazz can indeed be prayer.

The historical significance of The Jazz Singer far exceeds its technical achievements. It defined the challenges facing a generation of immigrants trying to embrace a new world without losing the old.

The questions of identity addressed by the film remain potent for any society struggling to balance integration and assimilation. It struck a chord with Italian, Irish, and Hispanic families as well as Jewish ones.

But the film plays above all to Jewish audiences, faithfully reflecting the world of its creators, who, like Jakie, sought to prove that filmmaking was not so far removed from the culture of their fathers. These artists too hoped to be “jazz singers singing to their God,” believing, like generations of cantors before them, that their talents were a divine gift and came with a mission. Once sound restored film to the realm of realism, Raphaelson, Jolson, and the Warner brothers used it to illuminate the complexity of their own Jewish identities – many aspects of which echoed in The Jazz Singer. In doing so, they provided an entire generation of Jewish immigrants, hitherto silent, with a voice. Of The Jazz Singer’s many messages, perhaps the most Jewish is those immigrants’ dream of finally finding a place where they belonged.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn addition to the film’s success, the soundtrack of The Jazz Singer became a blockbuster in its own right. Crowds gather outside Warner Brothers’ theater for the film’s opening, October 6, 1927