Secrets of Dreaming

When Sigmund Freud published his magnum opus, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), he expected it to change the face of the approaching century. Just to make sure it would belong to the new century rather than the old, he asked his publisher to stamp the binding with the year 1900. The study introduced his theories of the unconscious and how to treat the psyche, insights he described as a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence. He even speculated that his home would one day bear a plaque: “Here Dr. Freud discovered the secrets of dreaming.”

Freud attached great importance to his work, and thus to himself. His dogmatic opinions were born not only of conviction, but also of a certain measure of self-doubt. During his long career, he left lists of material for his biographers, destroying whatever he preferred to be forgotten.

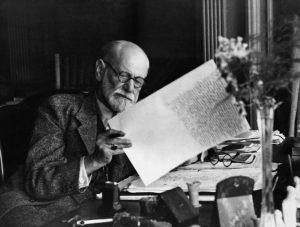

Freud reviewing the manuscript of Moses and Monotheism, his next-to-last work, in London in 1938. Returning to the subject of religion, which he’d examined much earlier in his career, Freud identifies the faith of Moses as none other than the monotheistic revolution of Pharaoh Akhnaten, then suggests that rebellious Jews killed their leader and created Judaism out of guilt

Mama’s Boy

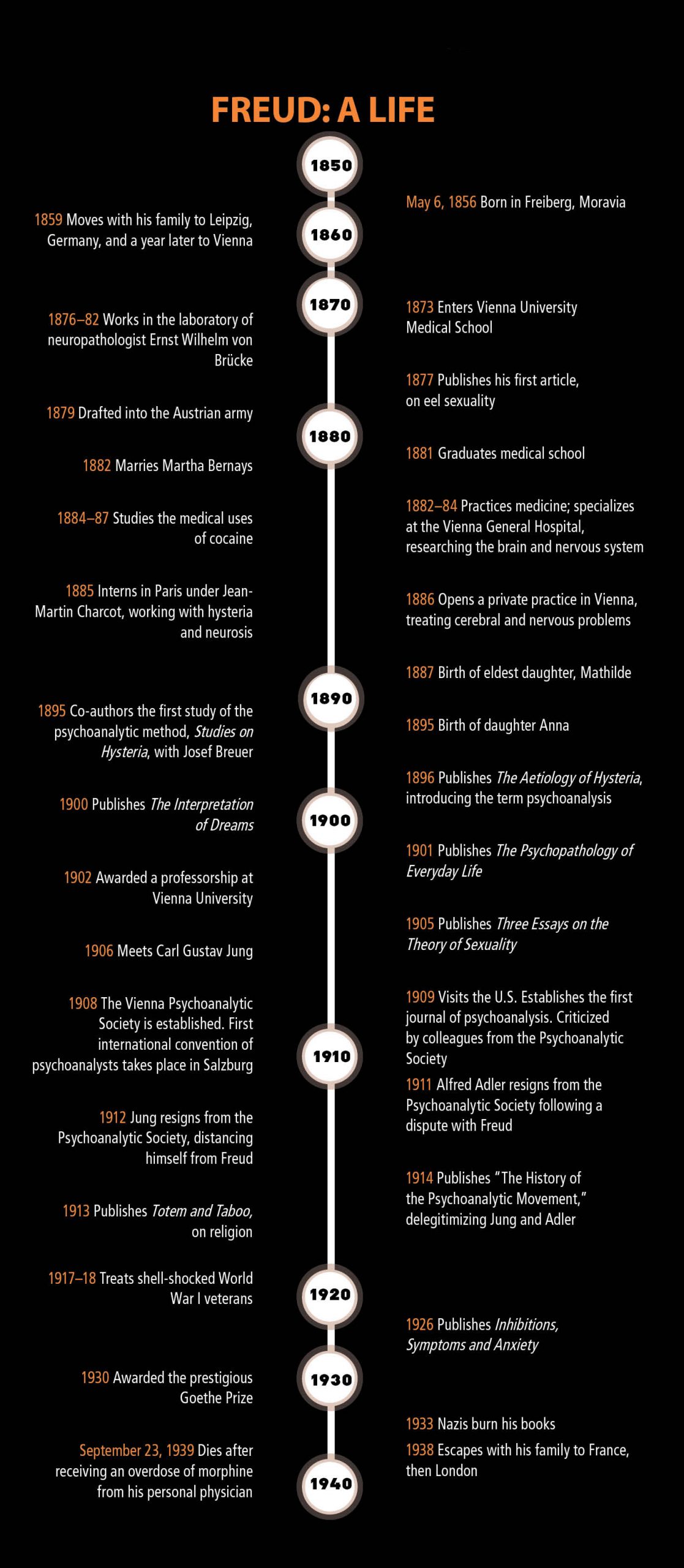

Sigismund Schlomo Freud was born in May 1856 in Freiberg, Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire. The first child of Jakob Freud and his third, much younger wife, Amalia, he subsequently changed his name to Sigmund, as Sigismund figured in too many anti-Semitic jokes. His Hebrew name (Solomon) is synonymous with wisdom, and his innate intelligence and curiosity were indeed evident from an early age. An avid reader with a quick grasp of languages, including Greek and Latin, he was frequently the top student in his class. His family was so sure he was headed for greatness that the daily routine at home revolved around his studies. His mother called him “my golden Sigi,” smothering him with love though she had seven other children. Freud later cited his family, and especially his mother, as the source of his rock-solid self-confidence.

Like many of their contemporaries, Freud’s parents were drawn to the big city. The family moved to Vienna when he was three. Freud grew up with the liberal, scientific outlook of the intellectuals of his age, famously rejecting formal religion. Yet he identified as a Jew, albeit – as his greatest biographer, Peter Gay, called him – a godless one. At age twenty-six, Freud married Martha Bernays, granddaughter of scholar Isaac Bernays (who had mentored Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, founder of the Neo-Orthodox movement in Germany). The couple had six children. In a 1926 letter to the Italian neurologist Enrico Agostino Morselli, Freud wrote:

Though I have been far removed from my ancestors’ religion for many years, I have never lost my feeling of solidarity with my people.

Freud even attributed his independent, original thinking to the fact that as a Jew, he was automatically an outsider. Almost all his colleagues were Jewish (see Jewish Science, p. 21), and he rarely bonded with non-Jews. Even his close association with Carl Gustav Jung, a pastor’s son, was tinged with a belief that only a non-Jewish disciple could spread psychoanalysis beyond Freud’s own Jewish circle. Tribal heritage was a recurring theme in his thoughts and ideas. In a letter to Sabina Spielrein, a Jewish patient and former lover of Jung’s who herself became a psychoanalyst, he wrote:

I am, as you know, cured of the last shred of my predilection for the Aryan cause, and would like to take it that if the child turns out to be a boy [Sabina was pregnant with her first daughter at the time] he will develop into a stalwart Zionist. … We are and remain Jews. The others will only exploit us and will never understand or respect us. (Ronald Hayman, A Life of Jung [New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2001])

Under Hitler, Freud’s books were burned by a frenzied mob in Berlin, and Gestapo officers persecuted him and his family. Although he fled to England with his wife and children in June 1938 (aided by British scientists, American diplomats, and French princess Marie Bonaparte), four of his sisters were murdered in concentration camps. Extraordinarily, Freud was also assisted by Nazi officer Anton Sauerwald, who was influenced by his writings. Ordered to seize Freud’s property, Sauerwald falsified his own reports, allowing the Jew to escape. Sauerwald even helped his Austrian personal physician visit Freud in London. Sauerwald was arrested in Vienna in 1945, but a letter written by Freud’s daughter Anna led to his release two years later.

At the last meeting of the Psychoanalytic Society in Vienna, Freud likened his exile to that of Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai, who famously declared as he fled the destruction of the Second Temple: “Give me Yavneh and its scholars!” hoping to rebuild Judaism outside Jerusalem.

We are going to do the same [for psychoanalysis]…. We are, after all, accustomed by our history and tradition, and some of us by our personal experience, to being persecuted. (Marthe Robert, The Psychoanalytic Revolution: Sigmund Freud’s Life and Achievement [New York: Harcourt, 1966]).

In his later years, Freud suffered from cancer of the jaw. In unbearable pain, he asked his doctor, Max Schur (whose family had accompanied the Freuds to England), to end his misery. The doctor administered heavy doses of morphine, and Freud died after Yom Kippur in 1939, as controversial in death as in life. His was one of the first recorded cases of assisted suicide.

Layer by Layer

Insatiably curious about human nature, Freud turned to science. In 1873, at age seventeen, he entered the prestigious Vienna University Medical School. Upon graduation, he turned to research under neuropathologist Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke, publishing dozens of papers on neurology, including an interesting study of the medical applications of cocaine based partly on his own use. But Freud was far from satisfied by the slow, careful advance of science step by cautious step, a few patients at a time. An intrepid explorer with a healthy disrespect for accepted wisdom, he was looking for a breakthrough. In his clinical work, he encountered numerous cases of partial paralysis, nausea, and pain with no clear physiological basis, and he was determined to locate the cause of the phenomenon.

A fellowship in Paris under renowned neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot only strengthened his resolve. Charcot used hypnosis to treat paralysis, even causing healthy volunteers to develop symptoms through hypnotic suggestion. How could conventional neurology account for such a thing? Even today, more than a century after the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams, most doctors prefer a physiological diagnosis. Freud, however, plunged into uncharted waters in search of an explanation. The turning point came when he and Josef Breuer, a Jewish doctor from Vienna, began treating “hysteria” – a mental disorder whose symptoms included paralysis, violence, fainting, insomnia, pain, and seizures, largely among women.

Freud’s first such patient, on whom he based his first independent case study, was “Elizabeth von R.” (her real name was Ilona Weiss). In 1892, at age twenty-four, Elizabeth sought treatment for severe leg pain, fatigue, and physical distress. Freud examined her, suggested massage therapy, and then asked about her background. Even now, doctors seldom take an interest in patients’ personal history. But Freud and Breuer believed that hysteria was intimately connected with a patient’s past, the more painful aspects of which could be accessed and discharged if one were prepared to expose and examine them. An admirer of ancient civilizations and an avid antique collector, Freud compared his therapeutic method to excavation:

This procedure was one of clearing away the pathogenic psychical material layer by layer, and we liked to compare it with the technique of excavating a buried city. (Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, Studies in Hysteria [Hogarth Press, 1955], p. 139)

The Listening Cure

In therapy with Freud, Elizabeth gradually peeled away the layers of her life story. She was the youngest of three daughters whose parents had desperately wanted a son. After her beloved father’s heart attack, she had tended to him until his death. Caring for her frail mother also fell mostly to Elizabeth. Her older sister died tragically of complications in pregnancy. And in one session, Elizabeth admitted she had been sexually attracted to her brother-in-law before her sister’s death, even thinking he would soon be free to marry her.

Freud deemed this web of secrets clinically significant: Elizabeth felt burdened by her parents’ needs, guilty about her feelings toward her brother-in-law, and lonely, orphaned, and helpless. The resulting intense inner conflict and emotional pressure had ravaged her physical health.

After analyzing many such cases, Freud and Breuer concluded that childhood experiences – some sexual – underlay patients’ suffering, which could be treated by helping them recall and discuss these painful events. The pair called it “the talking cure,” coining the term “psychoanalysis” only later:

Each individual hysterical symptom immediately and permanently disappeared when we had succeeded in bringing clearly to light the memory of the event by which it was provoked and in arousing its accompanying affect, and when the patient had described that event in the greatest possible detail and had put that affect into words. (ibid., p. 6)

Elizabeth learned to walk again, and even to dance. She married and became a mother. Though she subsequently denied that Freud’s treatment had helped, he and Breuer felt they’d amassed substantial clinical evidence that she and many others had been healed through searching, empathetic, analytic discussion, avoiding surgery or other invasive medical intervention.

This was the first scientific formulation of a clear connection between mind and matter – between a destructive emotional event and a physical, pathogenic consequence – laying the foundations of psychoanalytical theory and Freudian influence on modern thinking.

The drama of this moment, coming as it did during a period of tremendous progress and modernization, is often overlooked. Amid the rise of Darwinism, the dawn of genetics, and dizzying technological, medical, and industrial innovations, Freud – a prominent graduate of one of the world’s premiere medical institutions – had abandoned both stethoscope and microscope. He’d dared to ignore safe, concrete neurological and physiological concepts, proposing instead the intangible, unverifiable ego and id.

On the Edge of a Volcano

Freud’s early works on trauma and dreams contain the kernel of his later thought. Written more than ten years after he began his collaboration with Breuer, The Interpretation of Dreams was the cornerstone of an edifice Freud erected in the very heart of Western culture. According to Freud, the mind (or psyche) comprises conscious and unconscious elements, and dreams are in fact “the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind” (Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams [Macmillan, 1913], p. 483). In dreams, the mask of everyday life falls away, unveiling the forces that control our behavior: deep-seated and dangerous sexual and aggressive urges, an overwhelming sense of self, trauma, contempt, jealousy, and guilt.

Civilization is humanity’s attempt to impose order on this inner chaos. The resultant mental discomfort is the basic neurosis affecting all human beings. Freud broadened his original notion that trauma leads to neurosis by showing that even battling one’s most elementary instincts can cause suffering. The Interpretation of Dreams describes the complex structure of the mind and its ramifications, and suggests methods of dream interpretation that can minimize conflict and promote emotional balance.

For forty years, from the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams until his death, Freud worked obsessively, treating patients by day and writing late into the night. Not surprisingly, he viewed work as no less important to a healthy, normal existence than the capacity for relationships. His own articles, lectures, and correspondence fill twenty-four volumes – testimony to a life of true industry.

Freud was a gifted writer, receiving the Goethe Prize for German literature in 1930. His ideas are rich and diverse, and his works are literary pearls worth reading in the original, even in translation. Any attempt to summarize this oeuvre in a few paragraphs would be futile. But we might usefully examine how Freud altered our concept of the human mind.

We each perceive ourselves as a unified consciousness, preserving one identity over time. I can recall my personal history and associate it with myself and my name. I can identify the people around me – friends and enemies. That familiar pronoun “I,” which trips off my tongue, represents my core, what I think of as myself. What’s more, I believe I’m the master of my thoughts and choices. I can choose whom to marry, where to vacation, whether to eat meat or be vegetarian, or whether to study accounting rather than psychology. I consider all these actions mine, giving me a sense of wholeness. Even occasional insecurity doesn’t detract from my sense of self.

Freud’s research persuaded him that all this is sheer illusion. In fact, the psyche is not one uniform personality but a multifaceted organism, its many voices rarely in sync. Conflicting needs battle one another in a torrent of emotions.

Freud divided the psyche into id, ego, and superego, each of which has its own rules, logic, values, and goals. The id is a crying baby demanding immediate gratification; the superego is the adult, urging conformity with society’s morals and aesthetics. The ego seeks some middle ground between the two, enabling the individual to exist within the boundaries of his circumstances. If the tension between the parts of the psyche cannot be resolved, pressure builds, often resulting in some kind of outburst. In extreme cases, such an aberration can culminate in psychosis, even crime.

Our awareness, too, can cause personality to unravel. Freud compared our conscious thoughts to sand on the rim of a volcano. Lurking below this rim, out of sight, are the vast, untamed areas of the subconscious. The blazing volcanic core deep within represents our true driving forces, of which we are blissfully unaware – its secrets “censored.”

Each of us faces a choice: we can peer into the crater and its mysteries, or we can sit passively on the edge, ignoring the occasional rumblings and eruptions. Both approaches are risky. Those who dare to look inside may find the truth unbearable. (Freud’s favorite example was Oedipus. Disregarding prophetic warnings, this mythical Greek figure delves into his past and discovers he has unwittingly murdered his father and slept with his mother. Horrified, he blinds the eyes that have seen too much and banishes himself from his own kingdom.) Yet ignorance has its own perils.

Out of Control

Our sense that we freely control and direct our daily lives was another illusion Freud set out to shatter. In truth, he claimed, we’re merely following a “script” written in our childhood. “The child is the father of the man,” wrote Freud, meaning that our early history determines our later actions more than any of our choices. Our relationship with our parents and environment is critical in forming our personality. Thus, a mother’s response to her baby is, according to Freud, the single greatest influence on who he grows up to be.

The repressed parts of our personality also haunt us, Freud contended. Man is like a wild animal at the theater, well dressed and on his best behavior. Most of the time, he can keep his animal urges in check, but occasionally they’ll erupt, with disastrous consequences. For many scientists, such statements defy the notion of progress, which is based on order, logic, and control. Well aware that his radical remarks would be controversial – and disturbing – Freud nevertheless encouraged readers to accept that, far from being the masters of creation, we cannot even master ourselves.

The events that unfolded in Europe during and after Freud’s lifetime confirmed beyond a shadow of a doubt the unfathomable depths of humanity’s dark side. Yet he never despaired of mankind. For Freud, the purpose of civilization was to conquer the unconscious. Though he saw religion as an illusion, self-control as elusive and momentary, and violent, self-destructive urges as undeniable, he felt that the individual’s ongoing attempt to impose order was worth the effort. To quote his famous lecture ‘The Anatomy of the Mental Personality: “Where id was, there ego shall be”’ (Freud, New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis [Hogarth Press, 1933], lecture 31). Though the ego’s task is thankless, and the id sometimes prevails, the battle must go on. Man will always be a little neurotic, but we have to try.

Fleeing the Nazis, Freud ended up in London, surrounded by family and friends who’d also found refuge there. Freud on arrival in London, 1938, with his daughter Mathilde, (left), Ernest Jones, and daughter-in-law Lucie Freud

In 1931, when the menace of Hitler’s Germany was already apparent, Freud added a paragraph to his Civilization and Its Discontents:

The fateful question for the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent their cultural development will succeed in mastering the disturbance of their communal life by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction. … Men have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in exterminating one another to the last man. They know this and hence comes a large part of their current unrest, their unhappiness, and their mood of anxiety. And now it is to be expected that … eternal Eros will make an effort to assert himself in the struggle with his equally immortal adversary. But who can foresee with what success and with what result? (Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents [New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1962], p. 92)

Like so many of Freud’s ideas, these comments are as important today as they were then. Chilling as they are, they’re laced with his inherent optimism, and remain part of our discourse and dreams for humanity.