A Prophet in Exile

Poet, freedom fighter, and cosmopolitan in exile, Heinrich Heine bore the burden of an evolving modernity. A political prophet, Heine ranks among the European architects of modern Western thought. But how did his Jewish identity affect his singular career and intellectual world?

Born in Düsseldorf, Heine (1797–1856) was one of Germany’s greatest poets. His Buch der Lieder (Book of Songs, 1827) remains a best-selling poetry collection and has inspired thousands of melodies, most famously by Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn. Heine’s Romantic expressionist poetry could soar to a sublime beauty few could resist. His influence on German literature has been immense, but his philosophy is universal.

Heine spent his last twenty-five years in France, where he contributed significantly to the evolution of 19th-century European intellectualism. With his sharp wit and even sharper quill, he fought tirelessly for the rights of the individual, constantly needling the bourgeoisie. Nonetheless, he sincerely believed in the borderless fraternity of mankind, and supported at least some of the economic and social ideas promoted by Karl Marx, with whom he later corresponded.

Heine’s last eight years are legendary. Always delicate, he succumbed to a chronic illness that left him bedridden and wracked with pain. With rare courage, he refused all opiates, lest they cloud his judgment and prevent him from writing.

To some extent, Heine foresaw the horrors perpetrated by Western civilization in the 20th century. A hundred years before the rise of Nazism and Communism, he realized the evil that the new secular ideologies sweeping Europe would bring. He alluded to the bitter fate awaiting the continent as a result of this ideological upheaval, fearing above all Germany’s craving for power:

Christianity … has somewhat mitigated that brutal Germanic love of war, but it could not destroy it. Should that subduing talisman, the cross, be shattered, the frenzied madness of the ancient warriors, that insane Berserk rage of which Nordic bards have spoken and sung so often, will once more burst into flame…. Do not smile at the visionary who anticipates the same revolution in the realm of the visible as has taken place in the spiritual. Thought precedes action as lightning precedes thunder. German thunder is of true Germanic character; it is not very nimble, but rumbles along ponderously. Yet, it will come and when you hear a crashing such as never before has been heard in the world’s history, then you know that the German thunderbolt has fallen at last. (Heine, The History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany [1834])

A few sentences later he warned:

A play will be performed in Germany which will make the French Revolution look like an innocent idyll. (ibid., quoted in Yigal Lossin, “Heine: His Double Life,” p. 58)

Heine also dreaded Communism. Despite his friendship with Marx while both were exiles in Paris, Heine wrote in 1855, the year before his death, in the preface to the French edition of his book Lutezia (“Paris” in Latin):

This confession, that the future belongs to the Communists, I made with an undertone of the greatest fear and sorrow…. Indeed, with fear and terror I imagine the time, when those dark iconoclasts come to power: with their raw fists they will batter all marble images of my beloved world of art … they will chop down my Laurel forests and plant potatoes and, oh!, the herbs chandler will use my Book of Songs to make bags for coffee and snuff for the old women of the future. (Lutezia [DHA edition], vol. 13/1, p. 294)

Gazing prophetically into the 20th century, Heine foresaw monsters that would surpass all malevolent beasts since antiquity. He hoped his contemporaries’ grandchildren would be born “with especially thick skin.”

Baptism of Flesh, Not Spirit

Despite his universalism, Heine was well aware of his Jewish roots. His parents’ home in Düsseldorf typified German Jewry in the early 19th century. The Enlightenment had already weakened German Jews’ attachment to tradition, although they still paid lip service to Jewish custom and festivals. Many of Heine’s contemporaries even converted to Christianity, as did he himself at age twenty-eight, mainly to become eligible for a post in the civil service. He called baptism his “ticket to European culture,” but it failed to bring him any concrete benefits.

Heine was profoundly influenced by the emancipation and equality introduced by the French Revolution and spread throughout western Europe by Napoleon’s conquests (Düsseldorf, Heine’s hometown, was one of Napoleon’s three German duchies). Distancing himself from his early Romanticism, he deployed irony and satire against conservative forces in Germany – particularly the Prussian chancellor Metternich – which were methodically erasing Napoleonic freedoms from the law books. One particularly biting article on German censorship (published in 1827) read:

The German Censors —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— idiots——— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— —— ——.

(Ideen: Das Buch le Grand [Ideas: The Book of Le Grand], ch. 12)

As barrier after barrier to Jewish integration into general society fell away in Europe, despite political attempts to slow progress, traditional Jewish identity absorbed tremendous shockwaves. Modern opportunities and intellectual trends challenged traditional lifestyles and spiritual values, offering unheard of alternatives. Pitted against a romantic, utopian worldview preaching equality and advancement for all, what had the antiquated Jewish ghetto to offer?

According to Israeli television producer Yigal Lossin, Heine’s internal contradictions forced him to lead a “double life.” Riding the intellectual wave then sweeping Europe, Heine was part of the creative forces shaping and distilling the new ideas for the public imagination. Yet he retained a perverse affection for the people he had ostensibly left behind. Although he occasionally mocked their unaesthetic appearance and outmoded beliefs, Heine never renounced his Jewish identity. References to Zion and the Bible abound throughout most of his works, and his German contains more than a smattering of transliterated Hebrew.

While far from religious, Heine was convinced that observant Jews (such as those he had met while visiting eastern Europe in his youth) led happier and more harmonious lives than his assimilationist friends. Despite their unkempt beards, soiled clothing, and foul odor, he preferred these heimish, Yiddish-speaking European Jews to the self-imposed repression adopted by his associates in order to copy their German neighbors.

Heine’s gloomy prognosis for Europe included real concern for the fate of his people if left at the mercy of the German race. He was sure that Germany’s rearmament spelled disaster for the country’s Jews: “I do certainly not belong to the demagogues in Germany – just for the very simple reason that in case of the latter’s victory, some thousand Jewish throats will be cut – the best ones first,” he stated in a letter to his brother-in-law Moritz Embden (his sister Charlotte’s husband), dated February 2, 1823. Heine also wrote:

If one day Satan … should be victorious, there will fall on the heads of the poor Jews a tempest of persecution which will far surpass all their previous sufferings … I shudder at the thought and an infinite pity ripples through my heart. (Lossin, p. 58)

In his last, pain-filled years, as if in final testament, Heine wrote Romanzero, three books of lyric poetry on Jewish themes: Histories, Lamentations, and Hebrew Melodies. The best-known poem in this collection describes the Sabbath princess, in whose presence the miserable, mundane Jew becomes royalty. On his deathbed, Heine reputedly dismissed his conversion, claiming: “I make no secret of my Judaism, to which I never returned, because I never left it” (ibid., p. 60).

Much has been written about the complex self-definition of modern German Jews. From Moses Mendelssohn to Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, from Theodor Herzl to Franz Kafka and Sigmund Freud, all sought to reconcile their Jewish identity and German nationality. Author Hannah Arendt, who inhabited this same German Jewish twilight zone, wrote that only Heinrich Heine could truthfully describe himself as both German and Jew (ibid.). The rift rent his heart.

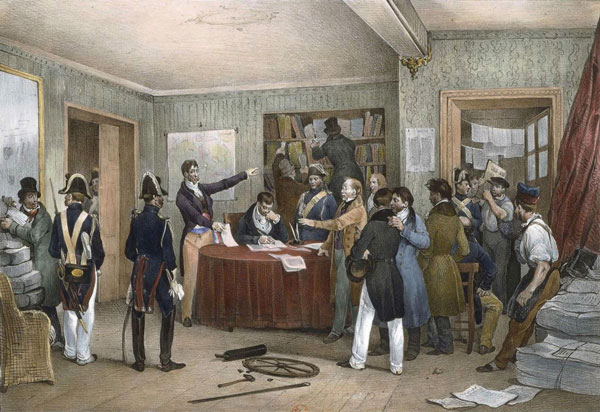

French National Library, Paris

French National Library, ParisSeizure of the printing press at the French daily Le National after journalists gathered there to protest censorship during the July Revolution of 1830. The revolution swung the country toward liberalism, prompting Heine to leave Germany for Paris. Painting by Victor Adam, 1830

Rewriting Jewish History

One mechanism by which Heine dealt with the tension within his soul was to relocate it to another time and place. In the early 1820s, he wrote Almansor, dramatizing Christian persecution of Muslims in medieval Spain. The play mirrored the anti-Semitic riots that spread throughout Germany in 1819 in reaction to Jewish demands for equal rights. Heine’s most famous, chillingly prescient line appears at the end of the first act. As Christians burn the Koran in the market square of Granada, Almansor’s friend Hassan warns: “That was but a prelude; where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people also.”

There is nothing Jewish about Heine’s tomb in the quiet artists’ neighborhood of Montmartre – except the stones left by Jewish visitors. The monument above the tomb was added in 1901

Heine also helped found Verein fur Cultur und die Wissenschaft des Judentums – the Society for the Advancement of the Science of Judaism. The society aimed to place Jewish culture and education on an equal footing with its counterparts, partly through scientific study methods. Headed by researcher and historian Leopold (Yom Tov) Zunz, Eduard Ganz, and Heine’s good friend Moses Moser, the organization sought to allow a new generation of Jews to integrate honorably into German society while maintaining a strong Jewish identity.

Illustration from The Rabbi of Bacharach, by German Jewish artist Max Liebermann

Heine thoroughly researched the Jewish history lectures he delivered at the Society for about two years prior to his conversion. In addition to reviewing the Bible painstakingly, he explored the Passover Haggada, pored over Christian history, and collected documentary evidence on the life of Don Isaac Abarbanel, the famous Spanish Jewish leader expelled from Spain along with the rest of the country’s Jews in 1492. This scholarship apparently led him to begin a historical novel, The Rabbi of Bacharach. This genre was wildly popular in Germany, and Heine’s would have been the first historical fiction with a Jewish theme. But he abandoned the idea, stashing the pages in his mother’s home in Hamburg; some were destroyed by fire in 1833.

From Bacharach to Damascus

In 1840, the Damascus affair (see “From the Archives: With Thanks from Damascus,” Segula 15, pp. 61–2) mobilized European Jewry in an unprecedented fashion, changing Heine’s direction. Living in France, he authored scathing articles dismissing the blood libel and denouncing French politicians – including the prime minister – for not defending the accused Jews. To popularize his position, Heine also published three chapters of The Rabbi of Bacharach. The novel begins by discussing a classic blood libel:

There was another accusation which in earlier times and all through the Middle Ages, even to the beginning of the last century, cost much blood and suffering. This was the ridiculous story, recurring with disgusting frequency in chronicle and legend, that the Jews stole the consecrated wafer, and pierced it with knives till blood ran from it; and to this it was added that at the feast of the Passover the Jews slew Christian children to use their blood in the night sacrifice. (The Rabbi of Bacharach [1913])

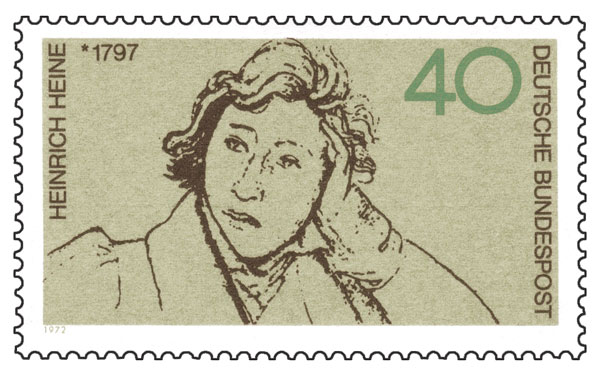

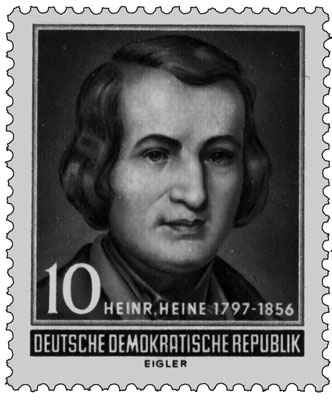

As a literary and cultural icon, Heine has been celebrated in numerous German stamps. Commemorating the centenary of his death in 1956 and, above, honoring the 175th anniversary of his birth, 1972

The opening scene finds Rabbi Abraham of Bacharach, Germany, and his childless wife, Sarah, seated with their guests around the Seder table on the first night of Passover, following the text of the Haggada as the great Jewish narrative moves from slavery to redemption:

Mournfully merry, seriously gay, and mysteriously secret as some old dark legend, is the character of this nocturnal festival, and the traditional singing intonation with which the Agade is read by the father, and now and then reechoed in chorus by the hearers, first thrills the inmost soul as with a shudder, then calms it as mother’s lullaby, and again startles it so suddenly into waking that even those Jews who have long fallen away from the faith of their fathers and run after strange joys and honors, are moved to their very hearts, when by chance the old, well-known tones of the Passover songs ring in their ears. (ibid.)

In these three curtailed chapters of his aborted novel, Heine managed to convey the bittersweet depth of Jewish history. The anguish and the privilege; the sublime as well as the ridiculous; escape from the ghetto as opposed to martyrdom; traditional versus modern Judaism – all struggle together in The Rabbi of Bacharach, as they did within the tortured soul of its author, Heinrich Heine.

Despite Heine’s premonitions, the Nazis failed to wipe out his people: stamp produced in the French zone of Germany after the Allied conquest, 1946