Nowhere to Go

In 1950, Jerusalem gained a new pilgrimage site: the Lion’s Cave, located in the Muslim graveyard of the city’s Mamilla neighborhood. The man responsible for this innovation was the director of Israel’s Ministry of Religious Affairs at the time, Shmuel Zanwil Kahane. This is his story.

As the armistice agreements following the War of Independence redrew the new state’s borders, Kahane faced a major challenge. Though Israel had survived, its Jewish population could no longer access most of the holy sites Jews had dreamed of for generations and visited before 1948. The Temple Mount, the Western Wall, in fact the entire Old City was beyond the border fence dividing West Jerusalem from the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. What pilgrimage destinations remained?

Unfazed, Kahane set about creatively filling the void, developing the Tombs of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem, the Rock of Destruction in Eshtaol, near Beth Shemesh, and the graves of sundry Talmudic sages in the Galilee. His crowning achievement was David’s Tomb, on Mount Zion, which was primed to be the most important Jewish shrine in the country. Alongside it he established the Chamber of the Holocaust, among the first Holocaust commemoration sites in Israel, and ran what amounted to a one-man counseling service for survivors.

But Kahane’s efforts were not always well received. At the Lion’s Cave dedication, in September 1950, most of the attendees were Yemenite immigrants reciting Psalms. Maybe that’s because the site’s purported holiness was based mostly on ancient Jerusalemite traditions recorded in medieval travelogues. The sign at the entrance read:

Legend has it that the bodies of fallen Jewish warriors from the Hasmonean wars were brought to this cave. When the Hellenist [forces] came to defile [the corpses] the next morning, they found a lion guarding the cave entrance […]. Located on the basis of descriptions by disciples of Nahmanides and the Tosafists. (Israel State Archives, GL-13/6299)

Many criticized the cave’s “discovery” and development. Prof. Moshe Avneimelekh wondered:

If the cave has neither scientific nor religious value, and is distinguished only by an obscure tradition of dubious basis, possibly Jewish or Christian in origin, why should it be set aside for special [religious] events? […] There’s a grave danger that people could interpret the Religious Affairs Ministry’s stamp of approval as complete affirmation of the place’s sanctity. (Moshe Avneimelech, “Falsification of History,” Be-terem 17, no. 182 [1953], p. 20)

Though Kahane knew he was on shaky historical ground, he deemed the site worthy of preservation – and development.

I saw it as my duty as a researcher to present the suppositions that had been made, even if they were mere legends […]. These tales have their own beauty and educational value, and in my opinion there’s nothing to be gained by suppressing them or relegating them to some musty archive. (“Ministry of Religious Affairs’ Position on the Lion’s Cave,” Ha-zofe, 17 Tishrei 5715/October 14, 1954, p. 3)

In conjunction with the Jerusalem Municipality, plans were made to turn the cave and its environs into one of Jerusalem’s main Jewish pilgrimage sites. Together with other nearby caves – plus sculptures other symbolic decor – it was to serve as a memorial for historic heroes of Israel. Alongside a frieze of a lion, a large gate with five entrances would lead to the cave.

The project never materialized, and today the site is barely accessible. The cave entrance is blocked, and the whole area utterly neglected. It’s no longer marked on Jerusalem maps or even signposted.

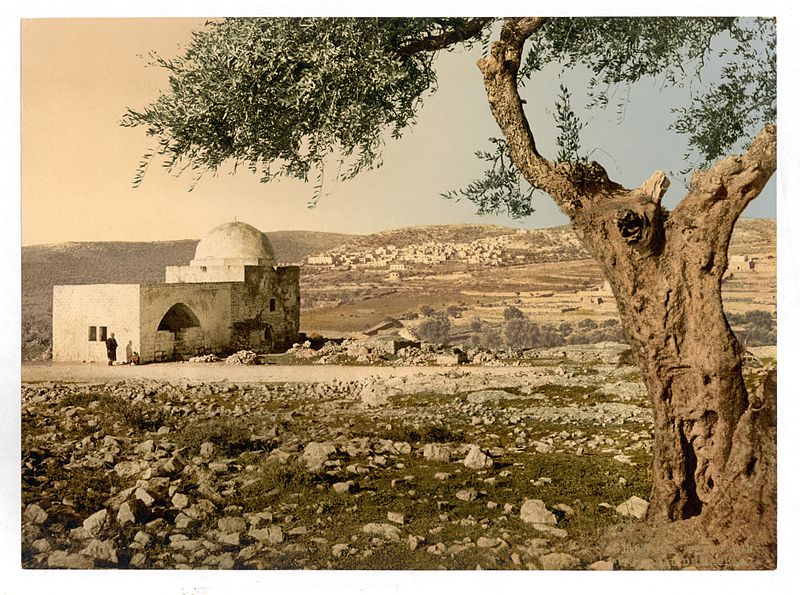

Sign leading to the Rock of Destruction, near the farming community of Eshtaol

Pilgrims’ Progress

Jewish pilgrimage dates back to the Bible and continued, though much diminished, after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Today, this custom has expanded exponentially, with thousands heading for Uman every year to pray at the tomb of Rabbi Nahman of Breslav in Ukraine. The Moroccan gravesites of famous rabbis are popular tourist destinations as well. Millions frequent Israel’s holy sites, in addition to the multitudes arriving for such special occasions as the anniversary of the death of Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai in Meron.

The Religious Affairs Ministry lists over 140 Jewish holy sites, including the House of the Shunamite Woman in Shunem (near Afula), the mikve of Rabbi Isaac Luria (known acronymically as the Ari) in Safed, Hebron’s Cave of Machpelah, and more. (Other spots have yet to gain official recognition, but they draw their own crowds. Among these meccas are the tomb of Grand Rabbi Gedalya Moshe Goldman of the Hasidic dynasty of Zvhil [d. 1950], located in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Badr cemetery; the Hasmonean tomb of Mattathias, outside Modi’in; and the shrine of the Moroccan rabbi David Ou-Moshe in Safed.) But seventy years ago, just after the founding of the State of Israel, the roster was much shorter: the tombs of several biblical kings, the graves of various Talmudic figures, and little else.

One of the earliest records regarding the few Jewish pilgrims to Jerusalem after its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE is the testimony of an anonymous Christian traveler from Bordeaux, France. Visiting Jerusalem in the fourth century, he observed Jews mourning among the ruins of the Temple Mount. In the sixth century, an Italian pilgrim from Piacenza recounted ceremonies performed by Jewish visitors at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. But we know almost nothing of other holy places – or the numbers they attracted – until the 11th–12th centuries, when the Crusades made pilgrimage a staple of Christian life. Descriptions by and of Jewish travelers multiply from then on, especially after the Muslims drove out the Crusaders, making holy sites more accessible to Jews.

With the rise of Zionism and the increasing ease of travel in the late 1800s, traditional destinations such as the Western Wall, Rachel’s Tomb, and the grave of the prophet Samuel (just north of Jerusalem) gained in importance and popularity. The 20th century added its own sites of Jewish and Zionist heroism, most notably the Judean Desert stronghold of Masada but also the graves of the Maccabees in Modi’in and Tel Hai, the Upper Galilee outpost where Joseph Trumpeldor was killed. Visits to these destinations became an integral part of Zionist education. The partition of Mandate Palestine into Jordan and Israel – with revisions following the 1948 War of Independence – left most of the Zionist pilgrimage spots intact. Yet the traditional holy places remained beyond the Jordanian border.

Master of Ceremonies

Generally speaking, the holiness of a pilgrimage site derives from ancient legends and traditions rather than scientific fact. These stories, their origins shrouded in obscurity, are disseminated by believers, especially pilgrims predisposed to justify their long trip. Therefore, a humdrum location’s transformation into a sacred one is seldom subject to direct observation. But Rabbi Dr. Shmuel Zanwil Kahane extensively documented his involvement in the development of Israel’s Jewish holy sites, allowing a rare glimpse into how such places evolve and are even created.

Kahane (1905–1988) was born in Warsaw to a distinguished rabbinical family. His father was Rabbi Shlomo David Kahane, head of a rabbinical court and later the rabbi of Jerusalem’s Old City. Well-schooled both Jewishly and generally, Shmuel Zanwil earned a doctorate in Oriental studies from the University of Liege, Belgium. He lectured at the Warsaw Institute of Jewish Studies, ran the Yavne network of Jewish schools, and published extensively in the Jewish press. . After the outbreak of World War II, Kahane left Europe for Mandate Palestine, where he soon became secretary of the World Mizrahi Organization and then – after the establishment of the state – director of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, a post he held for over twenty years.

During this era, Kahane institutionalized religious Jewish life in Israel. He provided religious facilities and services nationwide, creating a system basically from scratch. But the holy sites were Kahane’s pride and joy. In addition to infrastructural planning and execution, he avidly collected – and even invented – the legends that gave them credence. Despite his academic background in Judaic studies, particularly the rationalist thought of Maimonides, Kahane valued Jewish folklore as authentic religious expression. He cherished the connection between the land itself – its geography and topography – and ancient Jewish history, creating a unique body of texts for each site. Kahane was still expanding the ministry’s list of holy places when he retired in the 1970s.

Different Story

Kahane used his government position to legitimize his activities, but in many ways they almost diametrically opposed the nationalism of Israel’s secular leaders. The state’s early landmarks idealized military heroism, particularly the modern variety. Thus, the Zionist ethos focused on Jewish sovereignty and the struggle to maintain or regain it, most famously at Masada, where the last Jewish rebels killed themselves rather than submit to Roman servitude.

Not so Kahane’s Chamber of the Holocaust, dedicated in the winter of 1949 in time for the fast of 10 Tevet, the date designated by the Chief Rabbinate for the recital of the Kaddish memorial prayer by all those who can’t pinpoint when their relatives perished in the Holocaust. This museum’s message was far from heroic. Plaques honoring vanished communities, the ashes of Holocaust victims, gruesome artifacts such as garments made of Torah scrolls and soap allegedly derived from corpses – all emphasized the helplessness of Jews in the face of German brutality. The Chamber was a far cry from the Ghetto Fighters Museum, established only months later in the north of the country, whose emphasis on Jewish resistance set the tone of Holocaust commemoration in Israel for a generation.

Neither were Kahane’s other sacred sites conducive to military valor and sacrifice. In the 1950s and ’60s, he marked the graves of the sages whose words fill the Mishna and Talmud: Rabbi Tarfon, buried in the Upper Galilee; Rabbi Gamliel, in Yavne; and Rabbi Meir the Miracle Worker, in Tiberias. Locations identified by Arab traditions – such as the grave of the biblical Jacob’s son Dan, near Beth Shemesh – became the basis of monuments embedding Bible stories in the national consciousness, thereby connecting the land to its history, layer upon layer. For Kahane, the Ari’s tomb in Safed was no less significant than that of Theodor Herzl in Jerusalem or Hayim Nahman Bialik in Tel Aviv.

All over the country, Kahane ensured that tales of martyrdom, scholarship, and religious fervor adorned the signposts and monuments designating holy sites. Jewish history was not merely heroic, but laced with such tragedy and suffering that even the nation’s survival was worth celebrating. The Vale of the Hurban, near Eshtaol, commemorated the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem; and Mount Zion was not only reputedly the burial place of King David, but the site of the Chamber of the Holocaust, and of a monument to the Old City synagogues leveled by the Jordanians in 1948.

In the Galilee too, Kahane left his mark. In contrast to the modern historic sites of the first Zionist colonies and Trumpeldor’s grave in Tel Hai, Kahane enshrined the resting place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai in Meron – complete with its annual Lag BaOmer procession – and the tombs of Honi the Circle-Drawer and King David’s faithful servant, Benaiah son of Jehoiada.

New Traditions

When the press protested that Kahane was encouraging primitive folk ceremonies long since abandoned by rational folk and neglected by Jewish tradition, he reacted sarcastically:

I don’t know when the enlightened community liberated itself from visiting hallowed remains, inasmuch as its pilgrimages to the graves of Herzl and Weizmann continue daily. Every visit to a historic site has both educational and national value. The content of that visit is open to criticism, but not the visit itself. (Letter to the editor, Haaretz, 29 Kislev 5707/December 3, 1956, p. 2)

Far from objecting on religious grounds, Kahane’s response reflected his view that pilgrimage site development was a cultural investment as well as a religious one.

Kahane’s landmarks emphasized Jewish heroism dating back two millennia as opposed to the recent sacrifices of classic Zionist pilgrimage sites. Betar youth movement members beneath the sculpture of the roaring lion commemorating Trumpeldor’s death at Tel Hai, circa 1940

The curator of Mount Zion – a title bestowed on Kahane by the minister of religious affairs – was not alone in his respect for folk religion, even if it went against the grain of official policy. A grassroots movement numbering thousands of pilgrims helped formulate the rituals observed at David’s Tomb, the Cave of Elijah, and the grave of Rabbi Gamliel. These practices spread to other regions of the country, even those with no history of pilgrimage. Immigrants from Islamic countries brought with them a rich pilgrimage tradition of their own. And whereas the ceremonies held in Meron and Tiberias simply continued generations of annual “wakes” honoring Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai and Rabbi Meir, in cities such as Yavne, Kfar Saba, and Beth Shemesh, Jews from North Africa in particular created their own shrines. So did the development towns and moshavim, whose inhabitants paved the way for pilgrims and shaped the rituals associated with local holy places.

Kahane had a feel for time as well as place, matching specific sites with appropriate festivals and memorial days. In addition to national commemoration of significant places and dates in the heroic struggle for Israel’s independence, Kahane carefully crafted his own ceremonies at sites he developed: New Year for Trees celebrations at the Terebinth of Abraham, in Beersheba; a Hanukka torch-lighting in Modi’in, birthplace of the Maccabees; and a “heroism day” in Biria, near Safed (associated with Benaiah son of Jehoiada). The occasions he added to the national calendar – especially at David’s Tomb – were characterized by blasts of the shofar, pilgrims in traditional folk costumes, and symbolic landmarks. A mass reacceptance of Jewish law was planned to be staged every Sabbatical year on Mount Zion, and the Vale of the Hurban was the sacred destination of choice during the three summer weeks of mourning for the fallen kingdom of Judea and its capital in Jerusalem. All lent new significance to the State of Israel, connecting Israelis to the Jewish people’s past and imbuing foundational Zionist values with religious meaning. It was a struggle for the country’s soul, and Kahane played his part to the hilt.

Epilogue?

Z. Kahane’s “sanctification” of the new State of Israel was lengthy and extensive – but only partially successful. David’s Tomb, for example, promoted by Kahane as the site in Jewish Jerusalem nearest to the Temple, remains popular despite the Old City’s return to Jewish hands and widespread skepticism regarding the grave’s authenticity. Other places, such as the Lion’s Cave, Abraham’s Terebinth, and the Cave of the Righteous, have disappeared altogether. The survival of a pilgrimage site seems linked to a combination of factors – the character or event commemorated there, its location and history, and the strength of the tradition behind it.

The Six-Day War also determined the fate of Kahane’s creations. After nineteen years of separation, the majority of the Holy Land’s ancient shrines once again became accessible to Jews. These sites soon dominated the list of Israeli-administered pilgrimage destinations. Just days after the war in 1967, for instance, on the festival of Shavuot, people began flocking to the Western Wall. Likewise, the tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron, Rachel’s Sepulcher in Bethlehem, and the prophet Samuel’s grave overshadowed more recently sanctified places.

The matrix of holy sites shifted unalterably once East Jerusalem and Judea and Samaria were included. David’s Tomb became just another destination in the pilgrimage city of Jerusalem, and attractions in the Beth Shemesh area vanished. The graves of the sages in the Galilee, however, many developed by Kahane, still captivate worshippers today.